Sign up for the daily CJR newsletter.

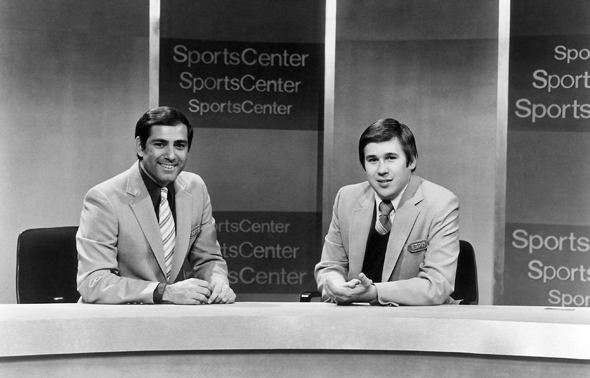

Birth of an icon George Grande, left, and Bob Ley, right, on the SportsCenter set at the ESPN studios in 1980. The network helped pioneer the nonstop news cycle that, for better and for worse, we take for granted today. (Associated Press / ESPN images)

When Ezra Klein left the Washington Post in January to start his own website at Vox Media, a big factor in his decision was Vox’s custom-built content management system, called Chorus. “They had the technology we thought we were inventing,” Klein told The New York Times. As it happens, that technology, which powers Vox’s growing media empire, began with a sports blog in 2003.

Vox’s sporty origins were no fluke. Turns out that sports media have long led the way in journalistic innovation. In 1898, Guglielmo Marconi demonstrated his new invention–the wireless telegraph–by sending updates from a regatta to the Dublin Daily Express. A year later, The New York Herald paid him to broadcast the America’s Cup. In the 1970s, Ted Turner bought the Atlanta Braves and Hawks so he could broadcast their games on his WTCG “superstation,” helping sell the nation on this new thing called cable television. WTCG became TBS, and soon we had ESPN (launched in 1979) and CNN (launched in 1980), pioneers of the nonstop news cycle.

The internet only accelerated sports media’s role as chief innovator. While studying digital innovation in newsrooms a few years ago, Carrie Brown-Smith, an assistant professor of journalism at the University of Memphis, noticed that the sports section tended to be the source of many of those innovations. “It was often a couple years ahead of the rest of the newsroom,” she says. Sports journalism has taken the lead, for instance, in audience engagement, creative use of technology, and experimental story presentation.

It makes sense. Sports fans are legion and passionate and always looking for new ways to engage with the teams and games they love; and sports’ (undeserved) image as the newsroom lightweight–the proverbial Toy Department–actually made experimentation seem less risky. “It’s probably the only time being considered the ‘toy department’ was a good thing,” says Jim Brady, who was one of the first sports editors of Washingtonpost.com in 1995, and its executive editor from 2004 to 2008.

Brady says sports writers were especially willing, and able, to make the transition to digital. “The metabolism of sports and the metabolism of the Web always seemed like a good match,” he says. “You have horrible deadlines, things that change at the last minute, a lot of ups and downs.” As Brown-Smith remembers a sports reporter telling her: “Every night is an election night in sports.”

‘The metabolism of sports and the metabolism of the Web always seemed like a good match,’ says Jim Brady. ‘You have horrible deadlines, things that change at the last minute, a lot of ups and downs.’

Before digital media, sports writers often were frustrated by how little of their copy actually made it into the paper: games ran late and they missed their deadline; sports features tended to be the first things cut for space. The internet solved that problem, and also allowed print journalists to match the pace of their television colleagues.

The infinite space online meant the sports section could serve as a reference as well as a news source. Brady remembers creating separate pages for every professional team and the biggest college teams. If the Post didn’t cover those teams, it linked out to outlets that did. That kind of aggregation is common now, but 20 years ago it was novel. And, says Brady, it got “a ton of traffic.”

Emily Bell, who was editor in chief of The Guardian‘s website (she now teaches at Columbia Journalism School and serves on CJR’s board), also discovered early on that experimenting with sports coverage paid off in big traffic. The Guardian was one of the first news sites to live-blog, with coverage of cricket matches on a blog called “Over by over,” which still exists today. It proved tremendously popular, and the format quickly spread to other sports and other subjects. By the 2002 World Cup in South Korea and Japan, The Guardian was live-blogging every match. Despite the time difference, which meant games often occurred in the middle of the night, it generated “the biggest traffic we’d ever had,” Bell says.

In 2003, Vox Media’s Tyler Bleszinski, a journalist turned public relations executive, was frustrated by the lack of Oakland A’s coverage in the San Francisco Giants-dominated Bay Area. His best friend happened to be Markos Moulitsas, of Daily Kos fame. Moulitsas encouraged Bleszinski to start a blog, and gave him access to Daily Kos’ platform. Athletics Nation’s take on the team was unapologetically fan-driven–the opposite of the “view from nowhere” journalism that media critic Jay Rosen began hammering on that same year. And Bleszinski wasn’t writing love letters to his team; he was doing journalism, analyzing A’s general manager Billy Beane’s sabermetric-driven management style, including several interviews with Beane himself.

By the end of 2004, Bleszinski had expanded Athletics Nation into a network of sports blogs. Three years later, what was now called Sports Blog (or SB) Nation had outgrown Daily Kos’ platform. Bleszinski hired Trei Brundrett, Pablo Mercado, and Michael Lovitt to build a new one. Brundrett, now Vox Media’s chief product officer, saw it as a chance to create something different, to build a platform around SB Nation’s readers and writers rather than jamming them all into a third-party CMS, as so many media sites had done (and continue to do today). This allowed them to create new article formats, such as StoryStream. Bleszinski says Brundrett understood “that sports journalism–and journalism in general–was something where a story doesn’t die once you write it. It’s an ongoing, organic thing that needs to constantly be updated.”

With StoryStream, a writer can organize her story (about a single game or an entire topic) into an easily navigable and shareable collection of articles, updates, and reader comments as it unfolds. Each new piece is instantly situated in the context of the larger topic, rather than being tacked on to the end or written through as the story develops. It’s faster, easier, and prettier.

SB Nation soon hired a CEO, raised millions in venture capital, and became Vox Media. It expanded to include sites covering technology, video games, food, real estate, fashion and, most recently, Ezra Klein’s explanatory journalism. Chorus is or will be–some of Vox’s recent acquisitions are still transitioning–the backbone of them all.

In recent years, the New York Times‘ sports department has been lauded for its innovative approach to the beat, both in terms of the range of subjects it covers (brain trauma, doping in horse racing, ultramarathoning, etc.), the depth it brings to its coverage, and the ways it presents its work online and in print. The most famous effort is Snow Fall, the Pulitzer-winning multimedia project about a fatal avalanche in Washington State that launched a hundred imitators.

Steve Duenes, the graphics director at the Times, says, “There’s no question that we’ve tried some new things first with sports projects.” One reason is that the sports editors were more open to experimentation and bringing the graphics and design teams in earlier in the story’s process. For Snow Fall, that meant that the visual and design components helped drive the story, rather than just serving as after-the-fact decoration.

Sports also have a wealth of visual information and data, both of which lend themselves to digital storytelling. For the 2010 Olympics, for instance, the Times created a sound-based interactive feature to illustrate just how close many race finishes were. For the Sochi Winter Games earlier this year, a script was written in Photoshop that allowed visual teams in the newsroom to create one large composite image of an athlete as the race progressed, as they did with US skier Mikaela Shiffrin’s gold-winning slalom run, that was actually more informative than the video.

And it was the ability to analyze the reams of data baseball generates that launched Nate Silver, journalism’s latest one-man brand. Before FiveThirtyEight became the numbers-crunching darling of the 2008 presidential election (and part of The New York Times two years later), Silver was using statistics to predict player performance for Baseball Prospectus, an outlet dedicated to analyzing baseball using sabermetrics. Now Silver has gone back to his roots, having taken his data-journalism talents to ESPN’s digital expansion in March.

At the bottom of all this innovation and risk-taking is sports fans’ insatiable appetite for news and information. Over the years, publications have taken advantage of this in various ways. In 2001, the Milwaukee Journal-Sentinel turned the region’s devout Green Bay Packers fan base into a source of revenue with a premium subscription service called Packer Insider. Emily Bell found that The Guardian‘s live blogs were enhanced when the writer and the audience interacted. Guardian sports editor Sean Ingle started having readers write in with questions and comments, which he would then post in the live blog. And Carrie Brown-Smith, of the University of Memphis, discovered that in many newsrooms sports journalists were more likely to use Twitter to interact with readers rather than simply pump out links to their stories.

SB Nation has always paid close attention to its readers, tweaking the commenting system in response to their complaints, for example, and deploying FanPosts and FanShots, which allow readers to contribute their own material. Social media is built into the platform. Audience engagement, says Trei Brundrett, “wasn’t just a strategy, it was a given.”

The Bleacher Report, founded in 2007, was built on audience engagement. It is now owned by Turner Broadcasting System (which reportedly paid $200 million for it) and has recently poached high-profile writers from places like ESPN and The New York Times. But in its first few years, the Report’s slogan was “the open source sports network,” and content came from contributors who were paid only in experience and profile badges (“citizen journalism for sports,” Mashable called it in 2008 ). You can disagree with its methods–many have–but you can’t argue with the results: 64.8 million unique visits worldwide in April, according to Quantcast. In April 2009, it was 2.4 million; that’s a 2,700-percent increase in five years.

Like SB Nation, Bleacher Report has a proprietary CMS that allows fans to easily have their say. Dave Finocchio, Bleacher Report’s co-founder and general manager, says 85 percent of the site’s content is now created by paid writers, who generate 97 percent of its views. But “we do maintain this minor league system,” he says, a program that develops new, inexperienced–and unpaid–writers. (Bleszinski, too, compared SB Nation’s FanPosts, from which the site has discovered some of its regular writers, to baseball: “It’s like having a minor league system right there where you can call up somebody.”)

Bleacher Report’s founders realized early on that reader data would be an important tool in deciding how to allocate then-limited resources. They paid attention to site analytics and which stories were being clicked on from their team-specific newsletters. It can be a fine line between covering a subject and chasing clicks–one that Finocchio acknowledges Bleacher Report hasn’t always managed well. But, he says, “I do think it’s very valuable for editors, especially, to know which topics, which storylines, are resonating with fans and which aren’t.”

Being “a little bit more sophisticated in how to leverage data,” as Finocchio put it, has given Bleacher Report an edge over its competition. In April 2014, it was the second-most popular sports website in the country, according to comScore, behind only ESPN. Even better, the majority of its visitors come from mobile devices, journalism’s next frontier.

In the future, sports journalism’s propensity for innovation may even put some of us out of a job. Narrative Science, the so-called robot journalism service, began as “Stats Monkey,” which could turn baseball data into an article, headline and all. Now it turns its bots loose on anything with a large amount of data, but finance and sports tend to work best. It has produced millions of recaps of Little League baseball games, for instance. The New York Times‘ “Fourth Down Bot” crunches 10 years’ worth of data to make predictions in real time of what NFL teams will do in fourth-down situations; it also takes coaches to task when they make what the bot considers the wrong decision.

Whatever comes next, the sports section will likely be the one moving the goalposts. “In America, the reality is that there is a cult of sports,” Bleszinski says. “Sports are about passion and that engagement. That, to me, is why it’s become the proving ground.”

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.