By May 12, authorities in India reported that an unexpected second surge of covid-19 in the country had caused 23 million infections and roughly 250,000 deaths. These were the official numbers—epidemiologists say the actual number of deaths, so far clustered in urban centers like Mumbai and Delhi, is two to five times the government estimates. In April, the positivity rate was 36 percent.

For photojournalists, tragedy is visible everywhere. Thousands of people have been turned away from overcrowded hospitals. The sky above mass cremation grounds, where the fires burn twenty-four hours a day, glows in the night.

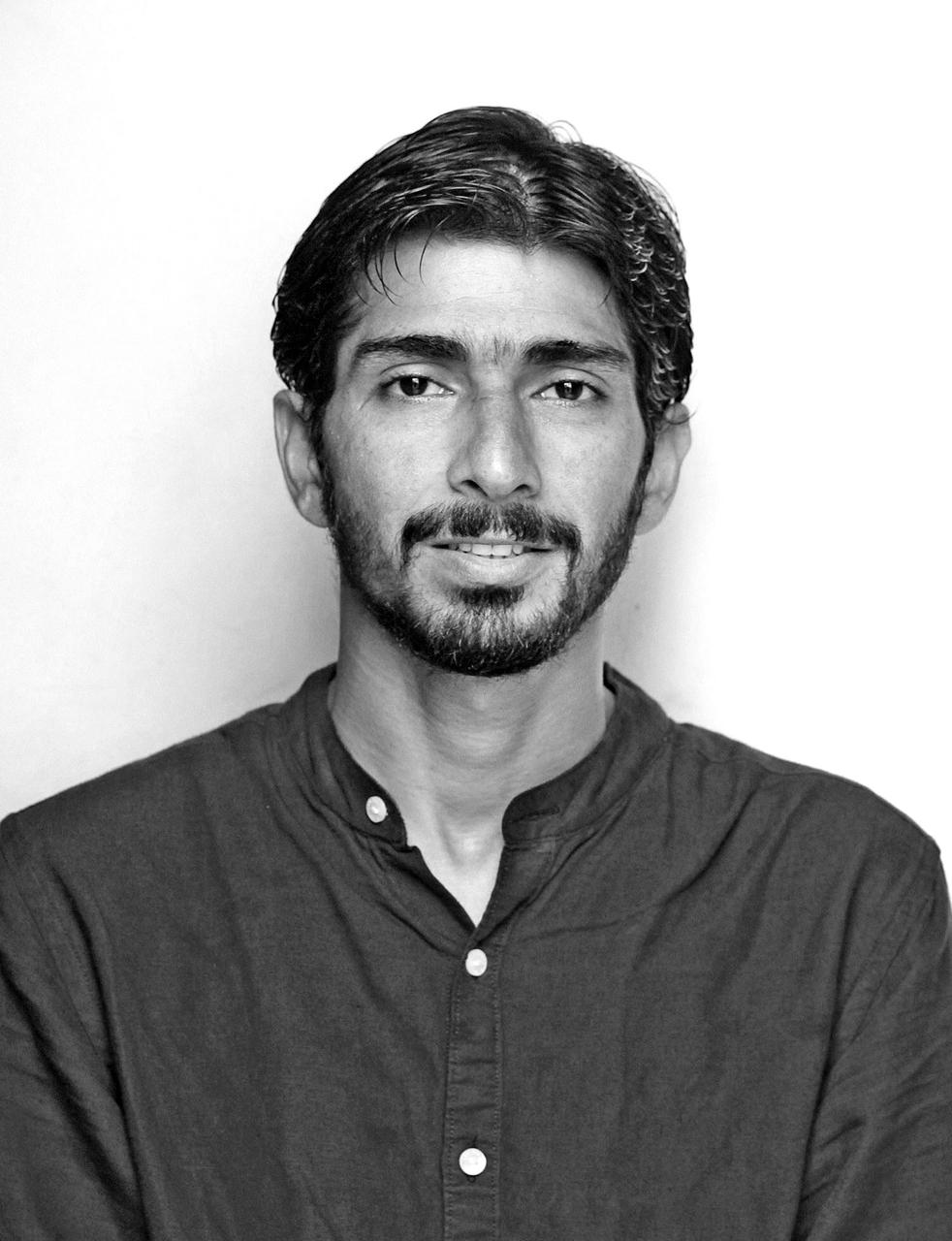

Adnan Abidi, a Reuters photojournalist from Delhi who is also based there, has been capturing the crisis in his hometown. Abidi has covered many traumatic events over his sixteen years with the agency. He was one of the first Indian photojournalists, along with Danish Siddiqui, to win a Pulitzer Prize for coverage of the exodus of the Rohingya people from Myanmar in 2017. He won a second Pulitzer for coverage of student protests in Hong Kong in 2019. His work regularly features on the front pages of the New York Times, the International Herald Tribune, The Guardian, the Wall Street Journal, The Independent, the Globe and Mail, and Time magazine.

With covid-19 affecting his home and members of his immediate family, though, Abidi has found going out to shoot increasingly difficult. Yet he continues, convinced that his work can serve to inform the public. “I’ve seen dozens of people die in the last month,” he told CJR. “Shooting as someone is dying in my hometown street. Children pressing their father’s chest. He died right there on the street. I was shaking when I was shooting.”

This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Image courtesy Adnan Abidi

The first time we spoke last week, you were almost too tired to talk.

This pandemic is the first time I’m facing something like this. No one in the whole world was prepared for this. Many of my relatives got sick, and many of my friends. They’ve now improved, but my family was very scared.

Image courtesy Reuters/Adnan Abidi

Tell me about this first photo.

This was at a cremation ground. I saw an entire family wearing PPE suits as they came to cremate their family member. In the photo, they are standing behind the dead person’s body, holding each other, as I look at them through the flames. I had asked their permission to shoot when they were coming in. But when I clicked that picture, they couldn’t see me because of the heat. It was really not easy to click that picture. The heat was so much that I couldn’t even stay there for ten seconds—I clicked and then came back rubbing my hands.

Are there other moments in your career that helped you prepare for this?

During the 2005 Kashmir earthquake, the Reuters team was staying in a room in a hospital near the border. In the evening quiet, we’d hear new patients coming in. I shot inside the hospital. That was the first time I saw kids with broken hip bones, broken hands. I was twenty-five.

Many people have asked me if I want to go to therapy, but I have never tried that. I cried many times in the field. In 2017, during the Bangladesh Rohingya influx, I was literally howling. My colleague was there, and she hugged me.

Everyone has his own mantra to deal with the burden. Mine is to talk it out with your close ones. I would call my sisters and friends—not my parents—and I would tell them everything. Sometimes you have to take it out, or you can’t work the next day. If you get affected mentally, you can’t work. Or you become biased. It’s good that you get emotionally attached sometimes, but it should never affect the transparency of your work. My job is to show what’s happening in front of my eyes. When you get attached to your subject, spend time with them, hear their stories, it’s very hard to control.

In Bangladesh, there was a twelve-year-old boy who lost his father. He came with his mother and seven younger siblings. He was earning money to support them by doing little jobs, holding umbrellas for people, that sort of work. Not begging. I shot him for seven or eight days.

He was a kid from a rural village, so he’d get excited when he saw my camera. When I pointed the camera at him, he would start smiling, and so I could not get the moment. But then a local politician drove through the refugee camp to distribute food and clothes, and he chased the car along with hundreds of people, ignoring me completely. That was the time. Running behind the car, he broke his slipper. I saw him in the crowd trying to repair it so he could keep up. I couldn’t bear it. I broke from inside. That day I wrapped my story.

Does it affect you differently, covering people in crisis in your hometown?

Seeing terrible things at home is very different. Last month my wife and mom had symptoms, and they tested positive. I was caring for them and working at the same time. When I’m going out in Delhi, I see that people are panicked. I want to control my emotions. When you panic, that’s when you make mistakes. You have to use your mind. Where are you safe? Know the limits.

Image courtesy Reuters/Adnan Abidi

Are there any moments that have been particularly hard to photograph?

For these photos, I was at a Sikh temple, where they give free oxygen to people who can’t afford their own. Families bring their sick relatives there. So this man came with his wife and daughter. They gave him oxygen for a couple of hours, but still his oxygen level was dropping. The doctors began to press his chest to get him to breathe. Then the family joined in. They were howling. His daughter kept pressing on his chest to breathe, and later they took him in an ambulance to the hospital. That girl—she was just doing her best to revive her father, but the doctor asked them to please take him to the hospital.

Then I had to come back home to care for my mom and wife. I wore a mask, headgear, glasses. In hospitals, I used PPE suits and sanitizers. Shooting at the cremation ground, I carry sanitizers—I sanitize every minute. When I come back, I clean myself as much as possible.

Image courtesy Reuters/Adnan Abidi

What are you trying to show in your pictures of the pandemic?

Sometimes people say these photos are beautiful, but I just want to show people what’s happening. Right now you don’t want to show people how good you are, with composition or whatever. What matters is how well you can convey the message through your pictures that it’s not safe out here. If people see my pictures on social, maybe they will be more cautious. Photographers are the ones who see everything—hospital, graveyards, cremation grounds.

Two days ago, I took this photo of a woman whose husband died of coronavirus. There was so much heat. We had to ask her to leave the heat and go outside, because she was so old. But as soon as her husband’s body went on the pyre, she came back and stood next to his body. She couldn’t stay outside. She came back in her sari to be with him, and she just looked up at the sky.

Normal people are not seeing this. I’m shooting a life-and-death situation here. It’s not a joke. It’s not just panic. It’s a real battle out there. It’s not easy. Frontline workers have seen it in past years. For the rest of us, we have never seen something like this. They know how to control the situation, but we are not aware.

As a journalist, you usually shoot sports, politics, protests, normal life. Now, for the last year or so, you just see death, misery. Things affect you sometimes. There’s a saturation point. If you see the same thing every day, you need rest so you can think of something new.

You took some time to rest over the weekend while you were recovering from the vaccine. Did you think of something new?

Now in my hometown things are improving and cases are going down. But the virus has reached the rural areas, the villages. This country is 70 percent agriculture; villages are the backbone of this country. It’s not an easy thing, to go into a village. You need contacts, because there are no journalists in those areas. We have no clue how we’ll do it, but we’re planning.

Amanda Darrach is a contributor to CJR and a visiting scholar at the University of St Andrews School of International Relations. Follow her on Twitter @thedarrach.