In February, Germany’s Bild, a daily assault of colorful photos and snappy headlines, threw a “Seafood and Security” party. Hosted by Julian Reichelt, the editor in chief, at Chef Fritz, a high-end brasserie in Munich’s trendy Haidhausen neighborhood, the event marked the final night of the Munich Security Conference, where policymakers had debated the future of the world order. Guests enjoyed a spread of mussels and liverwurst.

The party drew a who’s who of German power brokers, from the finance, health, and defense ministers to the CEOs of Lufthansa, Daimler, and VW. Mathias Döpfner—the CEO of Axel Springer, which publishes Bild—greeted Mike Pence, Ivanka Trump, and Jared Kushner. (“I know what people say and write about him, and it’s not my value set, but it doesn’t matter,” Döpfner tells me later, of Pence’s appearance. “That’s a social meeting.”) Pence gave an impromptu speech, about the value of German-American friendship (“Even though we sometimes disagree, the things that unite us will always be stronger”) and his recent visit to Auschwitz (“A place of horror, which also reminds us of the liberation and the value of freedom”). After Pence left, Ivanka talked about women’s liberty. Later that night, Bild featured photos from the party and a breathless report under Reichelt’s byline.

At 6 foot 7, Döpfner stands with the slightly hawklike stoop of a very tall man accustomed to peering down at everyone he meets. As the head of Axel Springer SE, one of Europe’s most closely watched media companies, he oversees not only Bild but also Die Welt, its more mature older sibling, as well as newspapers in Poland, Hungary, Slovakia, and Serbia and sites like Business Insider and Politico Europe. At the party, he wore a gray suit, though he typically favors casual attire—T-shirts and tennis shoes—in the style of Silicon Valley, from which he and his colleagues have taken inspiration. In 2016, Döpfner began offering tech luminaries the “Axel Springer Award,” luring Mark Zuckerberg; Jeff Bezos; and Tim Berners-Lee, known as the “founder of the World Wide Web,” to the company’s headquarters, in Berlin, for onstage interviews and coronations. In March, Zuckerberg came back for the company’s executive retreat. German politicians from across the ideological spectrum attend Bild’s annual summer fling. “It’s important that Springer is still a newspaper publisher,” Daniel Bouhs, a Berlin-based media reporter, tells me. “It keeps them politically relevant. No one wants to come to the annual reception of a classifieds company.”

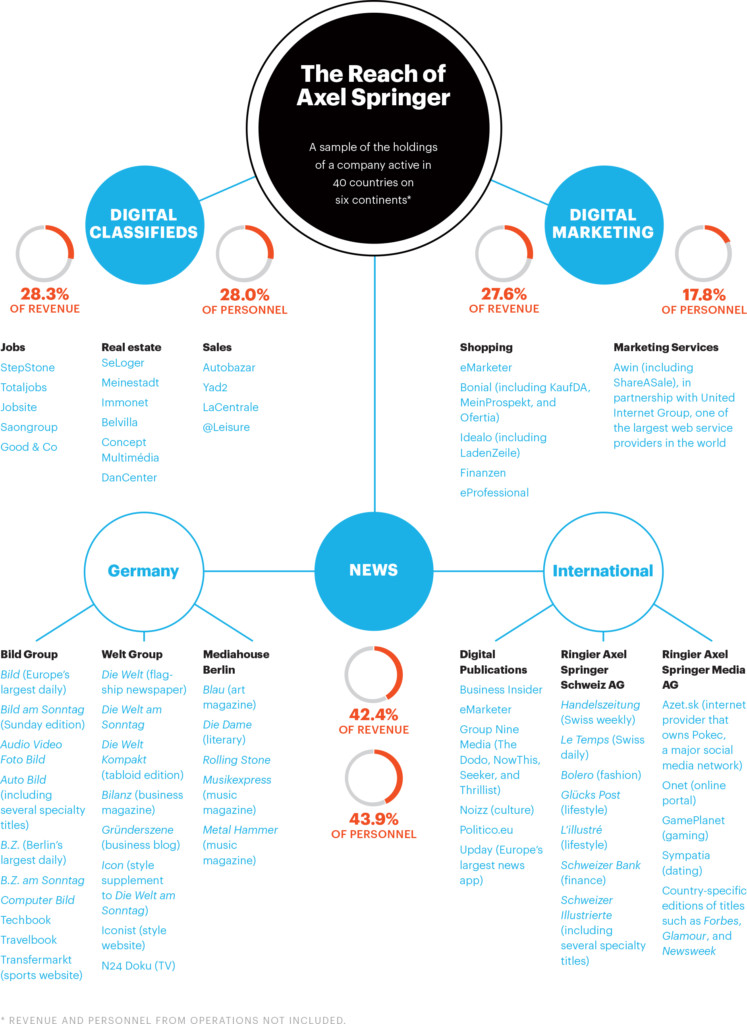

A journalistic force in Germany since the late 1940s, Axel Springer has achieved, thanks in large part to digital classifieds, what few other media companies have managed: to adopt a new, online identity. In 2006, it was a legacy publishing company making 1 percent of its revenue from digital products. Since then, Döpfner, 56, has sold off all of its German-language dailies except Bild and Die Welt, which have come to represent a shrinking part of the company’s business. Four-fifths of Axel Springer’s profits now come from digital offerings, many of them developed in-house or acquired in the past five years. Most are job boards, real estate portals, and price comparison websites. Today, Axel Springer is worth an estimated $6.8 billion, more than the New York Times Company. “Digital can be more profitable than print ever was,” Döpfner tells me. “And we’re further along than any traditional media company.”

Die Welt has arguably become more influential as an online outlet than it ever was in print, publishing opinion pieces from prominent German and European politicians. Ulf Poschardt, the editor of the Welt portfolio, says that “digital first” has become a company mantra. “It’s even firster. More first. What’s even more first than first? Super first. Hyper first. Or, as I realize Americans really like the German word über, it’s über first now.” This year, online subscriptions reached 100,000, roughly matching the paper’s paid weekday print circulation, in which the company has stopped investing. “We decided to think in stories, issues, attitudes, and scoops,” Poschardt adds, “not so much in the media channel where we’ll present them.”

Bild, which has seen daily print sales fall from 4.2 million in 2000 to 1.4 million today, remains Germany’s highest-circulation paper and retains a powerful place in politics and society. “Their reach has shrunken dramatically, but they’re still a multiplier—when Bild discovers something or uncovers something or pushes a campaign, other papers pay attention,” says Michael Haller, academic director of the European Institute of Journalism and Communication Studies in Leipzig and a longtime German-media analyst. Bouhs agrees: “It still drives the discussion.”

Whether journalism will be part of Axel Springer’s business in 20 years, however, depends on whether Döpfner can find a way to transform the company’s last legacy publications into successful moneymakers. Classifieds can’t subsidize the news forever. “In the analog days, classified ads were unthinkable without a newspaper,” he says. “Today, that is not the case—they can exist perfectly well without journalism.”

When Döpfner was named CEO, in 2002, rumor inside the company was that he reminded Friede Springer, the majority owner, of her husband—Axel Cäsar Springer, the company’s founder, a tall, dynamic, handsome man with an interest in music, politics, and journalism. Until his death, in 1985, he was one of the best-known, most controversial personalities in postwar West Germany.

Born in 1912, Springer, gifted with a passable baritone, toyed with the idea of becoming a singer. Instead, he took an easier path, apprenticing first as a typesetter and then as a reporter and editor at the Altonaer Nachrichten, a local Hamburg daily owned by his father, Hinrich. He was 21 when the Nazis took power, in 1933. Springer thought little of their racial views. The first of his wives—there would be five—was half-Jewish. Thanks to a string of cooperative doctors, he managed to evade military service, claiming to have a mysterious illness. (Decades later, in an interview, he admitted that it may have been psychosomatic.)

One day in 1944, sitting in a quiet house on the outskirts of Hamburg, listening to the unmistakable drone of British and American bombers flying overhead on their way to Berlin and Hanover, a 32-year-old Springer turned to his parents and made a startling announcement. “Soon, there will be freedom of expression in Germany again. And then I’m going to build the biggest publishing house in Europe.”

Hinrich was skeptical. Until then, his son had displayed minimal ambition. “I think the boy’s gone crazy, Ottilie,” he said to his wife.

“Don’t be so sure with this one,” she replied.

The exchange became one of Springer’s favorite anecdotes, repeated in countless interviews. It came true in part because of cleverness and in part because of good fortune: Hinrich’s printing presses survived the 1943 firebombing of Hamburg, an assault that claimed at least 40,000 lives and leveled most of the city. Amid the devastation, Springer began planning for a postwar future, printing novels by authors with no Nazi affiliation and stockpiling them quietly. By the time British troops arrived in Hamburg, in April 1945, Springer had squirreled away 50,000 books and 400 tons of paper.

Four-fifths of Axel Springer’s profits now come from digital offerings, many of them developed in-house or acquired in the past five years.

Springer’s prescience put him in a near-unique position. When the war finally ended, he was one of the few people in Germany with both a spotless political past and the resources to print newspapers. He soon started Hör Zu! (“Listen!”), a weekly guide to radio programs, and the Hamburger Abendblatt, a local daily; he used the profits from those ventures to buy Die Welt, an intellectual broadsheet, and to create Bild, inspired by Britain’s Daily Mirror. He mocked up the first issue of Bild himself, kneeling on the floor of his office with scissors and glue. “Write about people—for people,” he urged his staff. “And keep it short.”

By 1953, Springer owned three of Germany’s top-selling papers. Bild was Europe’s best-selling newspaper. Like the British tabloid barons he admired, Springer wasn’t shy about using his outlets to advocate for political causes, particularly German reunification. In 1958, he traveled to Moscow to privately pitch a reunification plan to Nikita Khrushchev, the Soviet premier. (The meeting, which lasted two hours, went badly.) Soon, Springer sought to enshrine his ideology as “corporate values”: recognition of Israel’s right to exist and Germany’s responsibility to the Jewish people, a rejection of extremism, a commitment to German reunification.

In the late 1960s, Germany’s growing student protest movement and its most charismatic figure, a sociology student named Rudi Dutschke, became regular targets in the pages of Bild. Demonstrators were described as hooligans and troublemakers. In April 1968, a day laborer with ties to the far Right shot Dutschke in the head, and blame for the assassination attempt was laid squarely at Springer’s feet. Thousands of protesters gathered at the company’s headquarters—steps from the Berlin Wall—clashing with police and setting loading docks and delivery vans ablaze. In Munich, hundreds of protesters stormed Bild’s offices; two people were killed in the melee.

Demonstrators likened Axel Springer to Julius Streicher, the publisher of the Nazi propaganda broadsheet Der Stürmer. One of Dutschke’s compatriots argued, “A provocative Bild headline does more violence than a stone hitting a police officer’s head.” The shooting, and the riots that followed, cemented the company’s reputation as a bastion of conservatism. Heinrich Böll, a Nobel Prize–winning author, wrote The Lost Honor of Katharina Blum (1974), about a woman hounded to suicide because of biased reporting by a thinly veiled version of Bild. Wolf Biermann, a German folk singer, immortalized the attack on Dutschke in a song, “Three Bullets for Rudi Dutschke”: “The first bullet came from Springer’s newspaper forest.” Today, Axel Springer employees arrive for work at the corner of Axel Springer and Rudi Dutschke Streets. (The company led a class-action lawsuit against the city of Berlin to prevent the memorial naming, to no avail.)

Tech Bro: Mathias Döpfner, the CEO of Axel Springer, takes inspiration from Silicon Valley. Photo: GORDON WELTERS/The New York Times/Redux.

Fifty years later, Springer’s “corporate values” have been updated. They now include standing up for “freedom, the rule of law, democracy, and a united Europe” as well as upholding “the principles of a free market economy and its social responsibility.” After 9/11, an addition was made: “solidarity with the free values of the United States of America.” Today, all 16,000 Springer employees are required to sign a value statement. Many can recite the principles by heart.

Döpfner says that the values continue to guide decision-making. The company won’t do business in China, for instance. In 2014, the Russian government passed a law limiting foreign ownership in media companies to 20 percent, and Springer pulled out of the market the following year, selling its controlling stake in the Russian-language Forbes to an independent publisher on the cheap. In 2016, in the midst of a growing crackdown on journalists in Turkey, the company sold its small stake in the Turkish broadcaster Doğan TV. (Deniz Yücel, a German-Turkish reporter for Die Welt, was imprisoned in Istanbul in 2017, and Axel Springer’s German papers reported on his case daily for almost a year until he was released.)

At the same time, Springer has been one of the few German media firms to stay invested in central Europe as a wave of authoritarianism has polarized the region’s politics. As part of a joint venture with Ringier, a Swiss publisher, Axel Springer co-owns dozens of print titles in the area, including the top-selling papers and dominant news websites in Poland, Hungary, Serbia, and Slovakia. These publications maintain a journalistic hold on the middle, which often places Ringier Axel Springer at odds with nationalist politicians on the right. In 2017, Polish officials held a week’s worth of parliamentary hearings on “foreign influence,” targeting Axel Springer, and called for German-owned papers to be “re-Polonized.” Mark Dekan, the CEO of Ringier Axel Springer, tells me, “People close to the government genuinely think I get orders from Angela Merkel.” When I ask Adam Michnik—a leading anticommunist intellectual who runs the Gazeta Wyborcza, Poland’s second-largest daily and a Ringier Axel Springer competitor—if there is any merit to the government’s claims, he laughs so hard that he starts to cough. “It’s complete idiocy,” he says. “Just government propaganda.”

Döpfner’s business in Poland, in particular, may depend on the outcome of elections this fall. “For very principled reasons, we would never give up in a country just because there’s pressure,” Döpfner tells me. “We still have room to operate independently in Eastern Europe. Should that change, then honestly, we would not continue to do business there, regardless of the costs.”

Döpfner’s office, on the 19th floor of Axel Springer’s Berlin headquarters, is spare. A prominent yellow Star of David sculpture is the only spot of color in a room otherwise dominated by white furniture and glass walls. After shaking my hand, Döpfner slouches on a couch below a gallery of windows that command a dramatic view of low, gray rainclouds scudding over Berlin’s skyline. Settling in, he asks, “So, what are we going to do?”

As a teenager, Döpfner played bass in a soul band and listened obsessively to Aretha Franklin records. He earned a degree in musicology and studied at the Berklee College of Music, in Boston, before taking a job as a music critic at the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, in 1982. (Music remains an obsession: Döpfner wrote obituaries for Whitney Houston and for Franklin, comparing both to opera diva Maria Callas.) After a decade as a reporter and critic, Döpfner worked as the editor of local papers in Berlin and Hamburg, then as the editor in chief of Die Welt.

In 2001, by which time Döpfner was head of the newspaper group, boardroom infighting had left the company floundering. Axel Springer posted a loss of 200 million euros—its first-ever year in the red. Friede Springer secured a majority of the company’s shares, making her one of the richest women in Germany, and tapped Döpfner the following year.

When he took over, Döpfner says, he was convinced that print’s days were numbered, and he sought to change the company’s model. He knew that newspaper publishers had traditionally bundled three distinct businesses—journalism, advertising sales, and classifieds—into one product, and figured that, in a digital world, there was no reason an interview with Merkel, an ad for toothpaste, and a job listing needed to be in the same place.

For a while, Döpfner’s digital evangelism faced strong resistance. In 2010, Axel Springer was still making more than 70 percent of its revenue from print. Its portfolio included everything from big papers to computer hobbyist magazines. Why mess with a proven formula? “The approach to experiments was that we had to be sure of the outcome,” Kai Diekmann, who spent 15 years as Bild’s editor in chief, recalls. “We had to be market leader at the end, or not bother trying.”

Illustration by Mengxin Li

Döpfner quickly restored the company to profitability, but recognized that the long-term prospects for print remained poor. At a corporate retreat in 2012, he impatiently asked his executive board why Axel Springer didn’t have teams coming up with the next Facebook. “The answer was, ‘Our best people aren’t working on these projects,’ ” Döpfner says. “Our best people were working on improving legacy businesses. We decided to change that.”

A few glasses of wine later, Döpfner green-lit what became known as the Axel Springer Silicon Valley project. He sent Diekmann and two other Springer executives to Palo Alto, where they lived in a rented bungalow on a cul-de-sac a few doors down from the former home of Steve Jobs, and around the corner from Google’s Larry Page. “We sent them to the valley without any concrete question or concrete project, in order to come up with new ideas,” Döpfner says.

Diekmann spent nine months in California, meeting with more than 300 start-up founders and venture capitalists. The stay, Diekmann says, helped him internalize Silicon Valley’s “fail fast” ethos—and absorb the cautionary tale presented by the rapid decline of so many US newspapers. “Too many colleagues in the American publishing industry avoided change and transformation,” he tells me. “I realized we had to be prepared to cannibalize ourselves, or we would get eaten by others.” Not long afterward, the company sent 100 of its editors and executives on a weeklong trip to California, booking them double-occupancy hotel rooms.

In the close-knit and traditional world of German publishing, Döpfner’s Silicon Valley obsession became a bit of a joke. Reporters weren’t sure what to make of the CEO of one of the country’s largest and most conservative media companies sporting a hoodie, or of Diekmann giving up his chauffeured car for a red Hyundai. Der Spiegel—Germany’s leading weekly, and a longtime Axel Springer rival—ran a story marveling at Diekmann’s transformation from clean-shaven German tabloid editor to stubbly Silicon Valley nerd, roaming Palo Alto and squinting at the 150 apps on his iPhone while wearing unlaced sneakers. “No one in Germany even knew what ‘disruption’ meant,” Haller, the media analyst, says. “Their competitors’ eyes were bugging out of their heads.”

The fact-finding mission, heavily publicized, was a clear sign that Axel Springer was serious about change. Just in case anyone hadn’t gotten the memo, Döpfner followed up a few months later with an announcement that roiled the company and rocked the German media world: Axel Springer was dumping the last of its local papers. Hör Zu! and the Hamburger Abendblatt, the cornerstones of the founder’s empire, were part of the sale.

Rivals saw the move as an abandonment of the company’s legacy. “Springer is opting not to come up with ideas to tackle these structural changes but rather to sell off newspapers and magazines at a time when they can still fetch decent prices,” Der Spiegel crowed. “The third-largest media company in Germany has apparently lost faith in the profitability of journalism.”

Döpfner tells me the opposite was true. “At the beginning it was seen as ‘They are murdering the company,’ ” he says. But the cuts, he believed, “would really help us to radicalize our transformation strategy.” The fact that Friede Springer controlled 51 percent of the company made it easier to take such a dramatic step. (In 2012, as a clear sign of support, she gave Döpfner 70 million euros’ worth of Springer stock as a gift.)

The sale netted 920 million euros, or about $1.2 billion. Much of the money went back into journalism: Döpfner went on a buying spree, acquiring N24, a cable news channel; Gruenderszene.de, a start-up-oriented news and jobs platform; and part of Magic Leap, an augmented-reality company based in the US that Axel Springer executives hoped would offer new ways to present reporting. Axel Springer also traded advertising space in its media properties and listings on one of its real estate portals for a small stake in Airbnb.

Döpfner invested in some companies with which most German readers are totally unfamiliar. Its purchase of Business Insider—in 2015, for $450 million—gave the site, based in New York, the resources to hire dozens of reporters and expand internationally. Business Insider now pulls in 92 million unique users in the US per month, more than The Washington Post. Axel Springer entered the social-media fray by acquiring a stake in Group Nine Media, the owner of Snapchat- and Facebook-friendly outlets including NowThis, The Dodo, and Thrillist. Politico Europe, a 50-50 joint venture between Axel Springer and Politico, launched in 2015. It now employs some 60 journalists covering European politics from Brussels and is projected to start turning a profit this year. “A lot of people didn’t think it would work,” Shéhérazade Semsar–de Boisséson, the publisher, says. “But there’s been a very strong commitment from Axel Springer to make sure this was a success.”

The company’s two remaining dailies have turned their focus to digital products. After Diekmann’s Silicon Valley sojourn, he asked Bild’s employees to gather in the newsroom. “I gave a speech and told them things were going to change,” he says. “They had to understand we are not a newspaper, we are a news brand that owns a newspaper.”

Video is a key part of the strategy. Bild’s Sunday print edition—an agenda-setter in Berlin political circles—is now followed up on Monday mornings with a livestreamed broadcast from a studio on the third floor of the Axel Springer building. Government officials call in live, from their kitchen tables or on their way to work, to answer “The Right Questions.” Down the hall, an open-plan workroom with a cultivated grungy feel houses the rest of the video department. Instead of couches, the room has pallets padded with red cushions, butted up against desks. A team of more than 30 video journalists produces subscriber-only original documentaries with high production values, often on true crime, as part of an effort to lure viewers behind the site’s paywall. Reichelt, the current editor, calls it “Project Netflix.”

Die Welt, for its part, became the first major newspaper in Germany to put articles behind a paywall. “There was bravery on Döpfner’s part to invest in a change process when it wasn’t clear it would work out,” Haller says. He then uses an old German expression: “They weren’t content to bake little rolls.” Today, Bild and Die Welt are major players in Germany’s online-news market. With nearly 400,000 online subscribers, Bild ranks fifth in the world for digital sales, and is one of three non-English-language publications in the top 10.

Axel Springer holds a press conference to announce its annual results to media reporters. In early March, Döpfner took the stage to declare Axel Springer’s days as a newspaper publisher a thing of the past. “We used to look at Bild’s print ads to see how the company was doing,” he told the room. “Now print ads represent less than 10 percent of our revenue. That’s a good illustration of the way the company is moving towards a purely digital structure.”

Bild, with its pithy headlines, investigative stories, celebrity gossip, outrage over “political correctness,” and nudity, can be hard to explain to foreigners. Imagine a national version of the New York Post with the power to set the agenda for the rest of the country’s media. “To rule Germany,” Gerhard Schröder, the former German chancellor, once said, “I need three things: Bild, Bild on Sunday, and the boob tube.”

Some aspects of Bild’s conservatism would be familiar to any weary observer of the US culture wars. In early March, for example, Bild’s front page was dominated by the news that a preschool in Hamburg had asked parents not to send their children to Mardi Gras celebrations dressed as Native Americans. A photo of a blue-eyed boy in a feathered headdress and the half-page headline “Now This Costume Is Supposed to Be Racist Too?” called to mind the “War on Christmas” faux outrage of Fox News. Bild is regularly sued for violations of Germany’s privacy laws, failing to blur the faces of alleged criminals and publishing identifying details of victims. A popular media-criticism website, BildBlog, is devoted primarily to chronicling its transgressions.

“The third-largest media company in Germany has apparently lost faith in the profitability of journalism.”

Reichelt, 39, took over as editor in chief in early 2018. He spent most of his career at Bild, moving from Axel Springer’s in-house journalism school to a job as a reporter; he served as a correspondent in Libya, Iraq, and Afghanistan. Under Reichelt, critics inside and outside the company say, Bild’s focus on politics has become sharper and more divisive. “It’s never been a left-wing paper, but it’s become more populist and aimed at the Right,” Moritz Tschermak, who runs BildBlog, says.

Bild’s politics can be hard to pin down, however. Under Reichelt, politicians from Germany’s far-right AfD party are rarely quoted, and Merkel—a generally popular figure coming to the end of a 15-year run as chancellor—has come in for frequent criticism. Lately, Bild’s reporting on refugees has shifted from sympathetic human interest stories to coverage of deportation delays and crime. Haller says that the paper reinforces stereotypes held in the minds of its readers. Reichelt tells me, “When someone who shouldn’t be in Germany kills a girl, it’s a huge topic for us. People who have no right to be here shouldn’t be here, and definitely shouldn’t be killing anyone.”

Every Monday, Reichelt invites a guest to critique the paper. The session, held on a red couch in the newsroom, is streamed online. Over the years, politicians from across the spectrum, along with celebrities and editors from competing papers, have made appearances. On a recent afternoon, dozens of staffers gathered as Reichelt bantered with the week’s guest, Peter Huth, Axel Springer’s corporate creative director.

The previous week, Bild had run a string of stories about retirees: rich retirees and poor retirees, retirees having trouble paying their rent, retirees getting hit by cars, a front-page story about a retiree who had been reduced to playing an accordion on the street while wearing a bunny costume to make ends meet. As the meeting drew to a close, Reichelt reminded staff that old people buy lots of copies of Bild. “Everything about retirement works really well,” he said. “So whenever a retiree crosses your path, grab them and find out what’s bothering them—and then do a story about it for us.”

Reichelt handed the microphone over for questions. Julia Brandner, the paper’s managing editor for digital, stood up. “I always get lost with all these retirement plans and options,” she said. “What if we offered a super-simple Bild-branded retirement account? I bet lots of people would be interested.”

“We could call it the Reichelt Retirement Plan,” Reichelt joked.

“We could promote it in the paper.”

“It’s a great idea, but these things are tricky for a reason,” Reichelt said. The start-up spirit was alive, if not always headed in the right direction. “If it was that easy, someone probably would have come up with it already,” he added. “But keep those ideas coming.”

In 1988, Döpfner spent a few months in San Francisco, working as a guest journalist at The San Francisco Examiner. He still treasures a T-shirt given to him by the paper’s owner, William Randolph Hearst III, bearing a cocker spaniel and the motto “In the afternoon, give the morning paper to someone who can use it.”

Thirty years ago, that slogan was a jab at the Examiner’s crosstown rival, the San Francisco Chronicle. Today, Döpfner is fond of using the shirt as a prop to make a point about the newspaper industry’s destructive history of infighting. In 2016, when he was named head of the Federation of German Newspaper Publishers, he gave a speech, unbuttoning his shirt to reveal the Examiner’s logo. “When we are against each other we make ourselves weak,” he told the crowd. “Together we are strong.”

The message was a call to arms against Google, part of a decade-long fight that has come to define Döpfner’s public persona. Calling Axel Springer “the biggest amongst the small,” Döpfner decided to take a stand on something that US publishers gave up on early: copyright. Arguing that headlines and teasers delivered by Google and other search engines are the intellectual property of newspapers, Döpfner said that Google should be paying Axel Springer to use its content.

In 2014, after years of lobbying, the German government passed a copyright law that let publishers charge for material that appeared in search results, such as headlines and teasers. In response, Google offered publishers a choice: let the search engine publish snippets of text from news articles for free, or else it will be just headlines and links. “Google has at no time either ‘threatened’ to delist publishers nor taken this step,” Ralf Bremer, a spokesperson for Google, says.

Bild and Die Welt held out on principle—but only for a few weeks. “We knew how it would end,” Döpfner says. It was as if Bild and Die Welt had been removed from the internet. Point proven; Axel Springer caved. “When your traffic goes down 85 percent in two weeks, we cannot say we benefit from Google,” he adds. “We depend on Google. There is no alternative.”

“No one in Germany even knew what disruption meant. Their competitors’ eyes were bugging out of their heads.”

Still, Döpfner refused to give in, and started working with publishers to lobby politicians across Europe for a law similar to Germany’s on the European level. At home, the campaign scrambled traditional political lines, uniting Google with the Pirate Party, an open-copyright, net-neutrality-oriented group; Axel Springer, den of conservatism, teamed up with Germany’s musicians and artists. (In December, emboldened, perhaps, by his new creative cohort, Döpfner showed up to the company’s Christmas party in drag, squeezing into a black corset and pink wig. “Is it intentional? That’s absolutely a valid interpretation,” he says. “To shake up a company through irritation, surprise, provocation, to encourage people to act unconventionally and speak up. . . that’s the inherent message.” Word got out, but nobody in Germany seemed to mind.)

In late March, the copyright law, known as Article 13, was approved by the European Parliament. What happens next is unclear, but Döpfner hopes that it will change the landscape for large media companies, giving them a revenue stream similar to what music companies earn from licensing online. “They cannot afford to boycott 500 million Europeans,” Döpfner says, of search engines. “That is just too big.”

It should be mentioned that Döpfner’s war on Google isn’t just about revenue for his company’s news platforms. As a major player in the classifieds market, Axel Springer is in direct competition with products like Google Careers, and dependent on search results for traffic to its classifieds businesses. “Google abuses its existing monopoly in order to create other market-dominating positions,” Döpfner tells me. “And that’s problematic.”

A new building is taking shape at the foot of the old Axel Springer office tower. Designed by Rem Koolhaas—a Dutch architect known for China Central Television Headquarters, among other major projects—the “Axel Springer Campus” is the culmination of Döpfner’s fascination with Silicon Valley. It’s a glass-walled box bisected by a literal valley: a 150-foot-tall diagonal atrium that will be flanked by open-plan workspaces and bridged by 13 walkways. “It’s of course another symbol for cultural change,” Döpfner says.

When the building is finished—likely sometime in 2020—it will bring together some of the thousands of Axel Springer employees now working elsewhere in Berlin. One of the centerpieces will be a new Die Welt newsroom, combining the N24 cable channel—recently renamed WeltTV—with its digital and print newsrooms.

More than a year before it’s scheduled to open, the building has already been sold to Norway’s sovereign wealth fund, Döpfner says, yielding a profit of more than 150 million euros. That makes Axel Springer a renter, with a 20-year lease on its own headquarters. It also gives Döpfner a deadline. As the share of Axel Springer’s business coming from digital classifieds and other nonjournalistic ventures grows, he’ll have to make sure that publishing space doesn’t become a graveyard.

In June, KKR, a private equity firm based in New York, offered Axel Springer shareholders a 39.7 percent premium over the company’s most recent stock price in an effort to take the company private. “We see it as a great sign for the company’s development, and also for our shareholders,” Döpfner said in a press conference announcing the deal. Friede Springer and Döpfner together own around 45 percent of shares; when the sale is finalized, as is expected, KKR will hold a healthy chunk of the rest.

That, Döpfner argued, gives Axel Springer some insulation against the stock market, and buys time to build digital projects that might need more money and patience. “We’re talking about organic investments in digital businesses—including digital journalism businesses,” Döpfner said. At the top of his list are investments in the company’s publishing portfolio—boosting Die Welt’s and Bild’s digital subscription efforts and Business Insider’s international expansion. For now, Döpfner is optimistic, he tells me: “I hope that the company is many times more profitable, and so powerful we are able to uphold the role that critical journalism plays in a modern democratic society.”

Andrew Curry is a journalist based in Berlin, where he has lived since 2005.