In the early hours one morning last January, Yacouba Ladji Bama, a forty-two-year-old investigative reporter, woke up at his home, in Ouagadougou, to the sound of shattering glass. He ran outside and found the rear windscreen of his black Hyundai sports car smashed in. Inside the car was a glass liquor bottle with a charred lip, still three quarters full of gas. On the back seat, surrounded by veins of melted upholstery, lay the detritus of Bama’s life: an umbrella, tissues, washing powder, batteries, a singed bundle of documents. Bama extinguished the flames, but the message was clear: someone wanted him to stop reporting.

Three weeks after the attack, I met Bama in his office in 1200 Logements, a suburb of the capital. He spoke to me from behind his desk, wearing a flat cap and thick-framed glasses, drawing his computer towards him like a shield. A gold-framed picture of Nobert Zongo—the father of investigative journalism in Burkina—hung on the wall behind him, among images of revolutionary leaders: Burkina Faso’s Thomas Sankara, Ghana’s John Jerry Rawlings, Congo’s Patrice Lumumba, Cuba’s Che Guevara. An air conditioner wheezed as it struggled to quell the Sahelian heat, but the room’s metal window shutters remained closed, to ward against onlookers. “I have to pay attention to everything now,” he said.

Bama seemed uneasy. He’d changed his daily routine, avoided remaining in one place for long periods, and was careful of where he ate and who prepared his food. A police investigation into the attack was underway, but he wasn’t sure who was behind it. “It could have come from a number of fronts,” he told me.

Yacouba Ladji Bama in his office at the Courrier Confidentiel in March. Photo credit: Clair MacDougall

The attack against Bama sent shockwaves through Burkina Faso’s small, tight-knit community of investigative journalists. Bama is editor-in-chief of the Courrier Confidentiel, one of the country’s leading investigative newspapers. The Courrier Confidentiel looks as though it belongs in a seventies sleuth film, with a loud, red-and-yellow design and brash front-page headlines, often featuring the word SCANDAL in all caps. It’s a modest paper by global media standards: bi-monthly, with a print run of five thousand. But the investigations it publishes resonate throughout the country, sparking fierce debates. Bama is widely followed on Facebook and regularly appears on radio and television, the preferred news media of Burkinabés (the name for citizens of Burkina Faso).

For years now, the Courrier Confidentiel has been running some of the hardest-hitting investigations into Burkina Faso’s ongoing war, part of a complex and sprawling regional conflict whose origins lie in a 2012 jihadist insurgency in neighboring Mali. Al Qaeda affiliates, backed by Tuareg rebels, overcame government defenses and imposed sharia law in northern cities for months until they were pushed out by French and local Malian forces. The conflict arrived in Burkina Faso in 2016. The country’s military is now backed by French troops, the United States military’s train and equip programs, and European Union financing. Aid organizations, including the Norwegian Refugee Council and the United Nations refugee agency, have warned that this war is one of the world’s fastest growing humanitarian crises—it’s claimed thousands of lives of soldiers and civilians, and displaced close to a million people, according to data compiled by the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project.

Few Burkinabés have access to timely and accurate information about the devastation that is unfolding in their country.

For journalists, reporting on the conflict has additional complications. They are expected to base their stories on government-issued communiqués. Official comments are provided largely by Remis Fulgance Dandjinou, the minister of communication and a former journalist. Presiding over press conferences in regal African tunics, Dandjinou is not afraid to tell journalists off for unpatriotic behavior. In the aftermath of an attack that killed dozens on Christmas Eve, 2019, Dandjinou posted a Facebook message on his widely followed account telling journalists to take a side on the battlefield. “There can be no neutral journalism in this situation where informing the public is crucial and defending one’s homeland and its survival is imperative,” he wrote. When I visited the gendarmerie headquarters in Ouagadougou, Guy Hervé Yé, a chief spokesperson, told me that journalists should encourage and support the work of security forces. “In Burkina Faso, sometimes we have the impression that some journalists laugh about our difficulties and they don’t want to speak about our victories; they don’t want to encourage our guys in the field,” he said. “I have the impression that Ladji Bama writes to do harm.”

The Courrier Confidentiel fresh off the press. Photo credit: Clair MacDougall

Given these limitations, few Burkinabés have access to timely and accurate information about the devastation that is unfolding in their country. The investigative journalists and editors I spoke to for this article complained of a culture of intimidation in which informants are afraid to speak and in which gendarmerie and military press journalists to name their sources. There is not a single television or radio show following the conflict, and only two journalists from state television have managed to embed with security forces.

Bama and his team focus largely on the experiences of men and women in uniform, piecing stories together using word-of-mouth anecdotes from those who have been terrorized and displaced. The Courrier Confidentiel has reported on allegations of corruption in the military, finding that soldiers’ “bulletproof” vests weren’t bulletproof, that armored vehicles malfunctioned, that the portable housing containers in which soldiers sleep were unable to withstand gunshots. The Courrier found that many soldiers weren’t being paid bonuses that they’d been promised for being on the frontlines. Bama doesn’t have the resources to send reporters out to the battlefield, but they piece together stories over the phone using encrypted apps such as Signal and WhatsApp, and interview soldiers who’ve recently returned from conflict zones. Sometimes they work with reporters using pseudonyms or anonymous bylines based in the north and east of the country, where the principal conflict zones are located.

“We are reporting so things will change and improve,” Bama told me. He called the government’s strategy to defeat jihadists a “complete failure”—one that has resulted from soldiers being insufficiently equipped, poorly trained, and lacking support. Civilians, too, are ill-protected and victimized. “There are attacks all over the country,” he said. “We are a long way from winning this fight if we don’t change our strategy.”

Bama and other Burkinabé journalists attempting to report on the conflict are up against an aggressive state campaign to control the narrative of the war. The government claims to be winning, despite mounting civilian and soldier casualties, lines of internally displaced people seeking refuge in camps, and widespread allegations of extrajudicial killings committed by both jihadists and government forces. In June 2019, Burkina Faso’s assembly passed amendments to the penal code barring citizens, journalists, and social media activists from publishing or circulating information on terrorist attacks or military operations without authorization from the state. The amendments were not reviewed by press associations or civil society groups, and they move well beyond standard laws to protect sensitive security information and prevent the circulation of false information. One clause states that the punishment for publishing material that “demoralizes” security forces even during “peacetime” is up to ten years in prison. Judges also have the right to block websites and remove content that broadcasts “false information,” of which the law offers only a vague definition: “inaccurate or misleading allegation or imputation of fact.”

Many journalists believe the new set of amendments was intended to target Naïm Touré, an online activist who in 2018 was convicted of inciting public disorder and sentenced to two months in prison. On Facebook, he’d posted that the politicians of the ruling party don’t “give a fuck” about the lives of the army and gendarmerie and called on civilians and the military to “stop the hemorrhaging while there is still time.”

An unveiling ceremony in May for a statue to commemorate revolutionary Thomas Sankara. Photo credit: Clair MacDougall.

Journalists believe the law also targets them, with language deliberately crafted to be vague so that any reporting that is critical of military operations falls under the ban. “It’s a blackout,” Guézouma Sanogo, the head of the Burkinabé Association of Journalists, told me. “We wait for the communiqué because no one wants to go to jail,” he said, referring to the official statements released by the ministry of defense. “You can’t approach the site of a terrorist attack without authorization. You can’t publish a sound or an image. But for how long? A minute, ten minutes a month?” he said. “Can you tell your neighbor?”

Yé, the gendarmerie spokesperson, denied that security forces ask journalists for their sources, though he said that journalists’ practice of speaking to anonymous sources within the security forces was eroding confidence among soldiers. As we spoke, he expressed an expectation that journalists side with security forces, telling me that the military should be “sacred” and needed to be protected from “humiliation.” His rhetoric called to mind a pattern that the Committee to Protect Journalists has documented throughout the continent—in which military officials leverage security concerns in order to stifle reporting.

As strategic interest in the Sahel from powers like the United States, France, and the European Union expands, will they match the millions of dollars they’ve spent on anti-terrorism training with support for press freedom and liberty of expression? Though the amendments to Burkina Faso’s penal code are mentioned in a 2019 Human Rights Report published by the State Department, neither the EU nor the US embassy in Ouagadougou have spoken publicly about the issue.

Burkina Faso is well known for its muckraking media culture, one strong enough to thrive under the twenty-seven-year rule of President Blaise Compaoré. Historically, the country has generally ranked high in the Reporters Without Borders World Press Freedom Index, and is now at 38 of 140 countries. Yet that placement belies the invisible red lines drawn by decades of violence and military rule.

A former French colony once known as Upper Volta, the country became Burkina Faso (“the land of upright people”) in 1984, when Thomas Sankara, a populist revolutionary hero, assumed the presidency. Though Sankara was celebrated for his anti-colonial and pan-Africanist ideas, Jean Claude Méda, a veteran journalist, described Burkina’s early years to me as “demoralizing,” a time when journalists were expected to be propagandists for the military regime rather than truth tellers. In the nineties, press freedom gained traction when François Mitterrand, the president of France, compelled African leaders to undertake democratic reforms as a precondition for financial aid. In 1991, Burkina’s constitution was written to include freedom of expression, and soon after laws were passed that allowed for the creation of independent media enterprises.

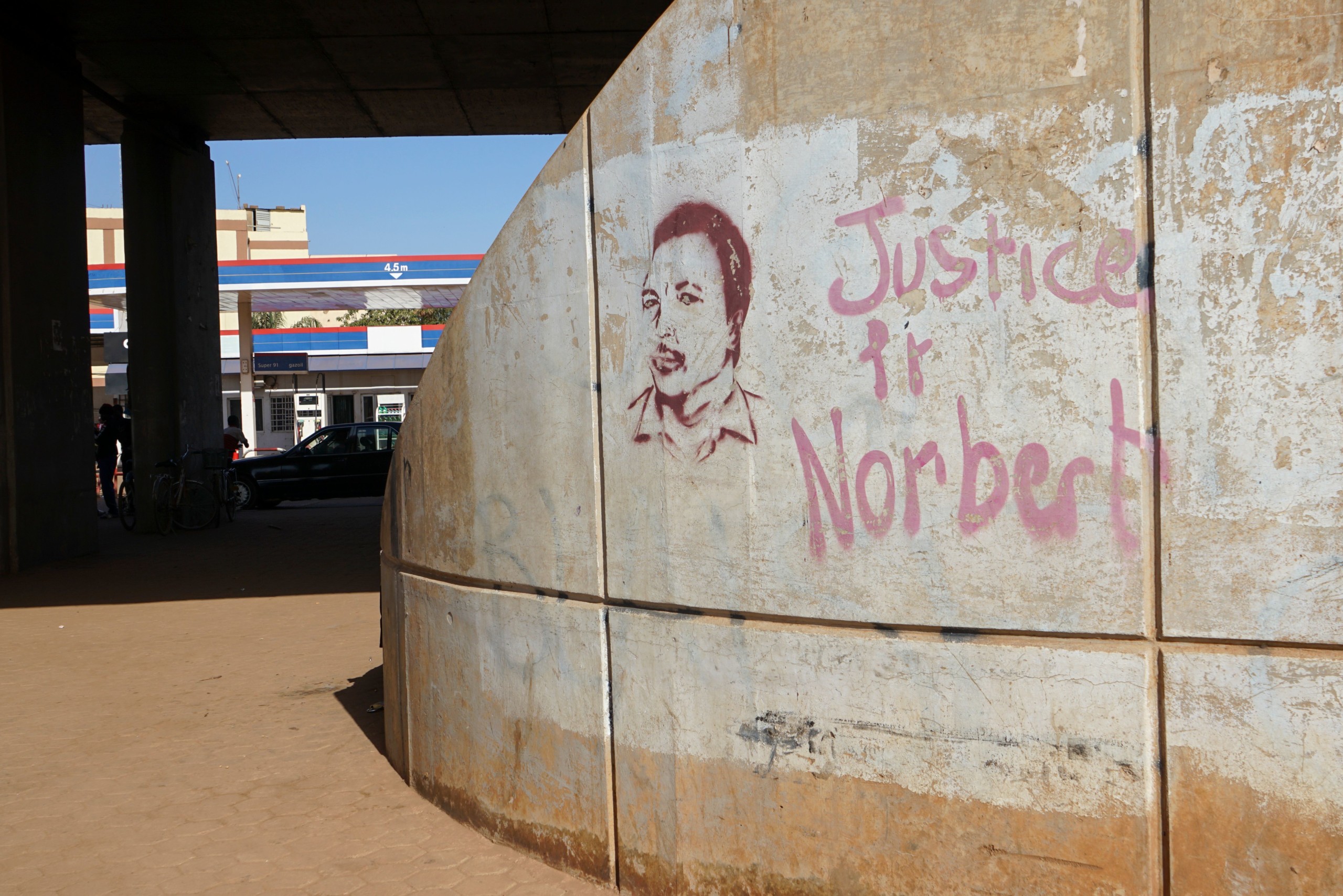

Stencil and graffiti call for justice for Norbert Zongo, an investigative journalist who was assassinated in 1998. Photo credit: Clair MacDougall

Five years later, Norbert Zongo, an investigative journalist for L’Indépendant, was murdered, his body burned inside his car on the shoulder of a dusty road. His driver, his brother, and a colleague were also killed. Zongo had recently begun an investigation into the disappearance of a driver who worked for François Compaoré, a wealthy businessman and the younger brother of Blaise Compaoré. Five of the six suspects implicated in the killings, all members of the presidential guard, were never prosecuted. Zongo’s death drew mass demonstrations—a rarity until that time—and in their wake new independent media outlets and investigative publications set up shop. Many believe that Zongo’s death paved the way for a more critical media that led to Compaoré’s undoing—in October 2014, he was overthrown in what Burkinabés call the “popular insurrection.”

The following spring, the case of Norbert Zongo was reopened. As independent media continued to expand, the government decriminalized libel and created laws that granted journalists access to official documents. This blossoming of the press came to an abrupt halt, however, when Ouagadougou was hit by deadly terrorist attacks in 2016, just months after Burkina’s first democratically elected government in almost thirty years, led by President Roch Marc Christian Kaboré, took power.

To Burkina’s most accomplished journalists, many of whom actively worked to bring about the 2014 uprising, the recent turn-for-the-worse for press freedom has been debilitating. When, they wonder, will they feel once again able to inform their fellow citizens, hold the government accountable, and shape the nation’s future?

Tiga Cheickh Sawadogo, thirty-four, became a reporter on the cusp of the 2014 uprising. “For a journalist it was a wonderful moment,” he told me. “There was excitement in the city, the people were shouting all over. Anyone you pointed a microphone at would speak.” The recent amendments to the penal code felt like a slap in the face, particularly for young journalists like Sawadogo, who believed they were coming of age in a new era.

Tiga Cheikh Sawadogo outside the offices of lefaso.net. Photo credit: Clair MacDougall

As a national security reporter for lefaso.net, the nation’s most popular news website, Sawadogo has been one of the few journalists reporting on claims of extrajudicial killings committed by the military. His colleagues call him “kamikaze” for his willingness to travel to conflict zones to pursue stories. He faces attacks and criticism for his work on and offline. “It’s really difficult for a journalist to write and say there were some murders in an area like Djibo,” Sawadogo said, referring to a city in the northern Soum province. “Actually, if you do that, the readers will say you are not a patriot or in support of your country.” In Burkina, the public holds a positive view of the military; both Bama and Sawadogo described being targeted by online harassment, which Bama suspected might be boosted by government officials. In the lefaso.net office, Sawadogo showed me comments on an article he’d written about extrajudicial killings that had been filtered out by the site’s moderator; they included death threats directed at Chrysogone Zougmoré, the president of the Burkinabé Movement for Human Rights. One commentor wished for everyone in Zougmoré’s home village to be killed; another accused him of being a terrorist.

Sawadogo’s interest in reporting on the conflict is in part personal. His family is from Soum province, and he has cousins who are out of school because of the jihadist attacks. (Schools in the north are regularly targeted.) When he travelled to Djibo, Sawadogo became aware of the stark divisions between the north—where jihadist attacks occur regularly—and Ouagadougou—a city of two million with drinking spots, packed markets, and arts and music festivals—that, on the surface, seems largely untouched by terrorism. If you look closely, though, you can discern traces of the conflict in the corners of the capital. Displaced women and children loiter around the streetlights and inside empty buildings, concrete slabs form barriers around the fancy hotels, metal barrels filled with sand surround military bases and police stations—and then there are the rows of graves of young soldiers in the city’s main cemetery.

Graves of soldiers at the municipal cemetery in Gounghin, Ouagadougou. December, 2019. Photo credit: Clair MacDougall.

In Djibo, the conflict is on open display. Last year, a colleague of Sawadogo helped him interview Oumarou Dicko, the mayor, just two months before Dicko was assassinated. That month, the mayor had made public complaints about the police for raping and killing residents and, in response, Djibo police filed a defamation suit against him. In an interview with Sawadogo and his colleague, Dicko accused the police of killing a mentally ill man and of raping a young girl. After lefaso.net published the remarks, Sawadogo’s colleague, who asked not to be named in order to protect his security, started receiving strange phone calls and suspected he was being followed. He stopped reporting, fearing for his safety.

“When you write something directly about the FDS,” Sawadogo said, using the French acronym for the Burkina Faso security forces, “you need to be careful.” Sawadogo has been warned by colleagues to slow down his reporting. He now avoids disclosing that he is a journalist when crossing military checkpoints. “Someone advised me that when I am working on these types of subjects regularly for months on end, you have to stop so people forget about you,” he said.

In early March, a massacre claimed the lives of forty-five people of the ethnic Fulani people in Barga and the village of Dinguila Peulh, areas in the north. The Collective Against Impunity and Stigmatization (CISC), a group that has rallied to stop violence against Fulani civilians, held a press conference in Ouagadougou and pointed fingers at community defense groups called the Koglweogo, along with volunteer defense forces, who have been recruited by the state and the state security forces. According to Human Rights Watch, the majority of documented cases of alleged abuses and killings committed by the Koglweogo, volunteer defense forces, and the military have targeted the Fulani.

In January, the National Assembly passed a law allowing volunteers from conflict zones to be mobilized, trained, and armed by the state. In March, Sawadogo was at a press conference announcing an investigation of those volunteers for killing people extra judiciously, among other allegations. The room was packed with journalists. Male tribal elders sat in heavily embroidered boubous and young Fulani activists with fashionable haircuts and sculpted afros leaned against the walls, filming on their phones. Sawadogo sat in the second row, dressed in a dyed fabric bomber jacket and skinny jeans, his boyish face still and focused.

“It was around 5AM that the people of Dinguila Peulh saw a column of more than a hundred men on motorcycles in black uniforms with weapons,” Daouda Diallo, the secretary general of CISC, told the crowd. “It was a very violent attack where even children were burned in houses and disabled people killed. Every man was systematically shot, even the old men.”

Daouda Diallo, of the Collective Against Impunity and Stigmatization (CISC), talks to Moussa Diallo, the organization’s media officer, at a press conference in Barga. Photo credit: Clair MacDougall

Afterward, I followed Sawadogo outside to a shady spot under a tree, where he interviewed a community official from the town of Barga and the brother of one of the victims of the massacre. The men allowed Sawadogo to record the interview, but declined to give him their names, photographs, or even their phone numbers. That was to protect the victims, they said.

“Can you tell us about what happened?” Sawadogo asked. The official from Barga, tall and dressed in a white kaftan and kufi cap, recounted how members of the Koglweogo had come months earlier and threatened to kill members of the community if they didn’t leave. According to CISC, men and boys aged eight to ninety were killed. “We beg the mercy of the government to ask the Koglweogo to stop what they are doing,” the man said. “The government should make the Koglweogo stop what they are doing. We lived in peace and harmony in our village, but we can’t understand why the Koglweogo said they will kill all of us. According to them we are terrorists.”

After the interview, Sawadogo jumped on his scooter and headed off to lefaso.net to file his story. In the following days, nobody was officially reprimanded for publishing stories on the press conference, but Radio Omega, a station based in Ouagadougou, was called into the Superior Council for Communications (CSC), Burkina’s media regulator, for airing interviews with alleged victims from Barga. The CSC has the capacity to issue fines and take shows off the air for libel, disturbing the peace, or inciting hate and violations of state security. Boureima Diallo, CSC’s director, told me that the council has recently acquired equipment that enables it to record every radio show across the country and keep archives for at least six months so that it can better monitor whether stations are adhering to its rules. When I asked him about the laws that restrict reporting on military operations, he replied that some information needs to stay confidential so as not to fall into the hands of the enemy.

“We do not want a war between the communities,” Diallo said. “We are in a country where people don’t understand their rights and journalists who are not well trained musn’t write what they want to write, and it’s not good for national cohesion; it could create a war, it could be more fatal than a gun.”

“The attack has galvanized me. It’s strange in this profession when people are going after you, it’s a sign that you are doing good work.”

When I next met Bama in his office, in April, there were five hundred confirmed cases of coronavirus in the country. The Courrier had been covering the story. “Will they tell us we are demoralizing the doctors?” Bama joked.

The police had yet to find out who set Bama’s car on fire, though they did commission a forensic investigation—which ruled it an accident. Bama was disappointed. “It’s like saying that a child was amusing themselves nearby and accidentally set the car on fire. It’s impossible at three o’clock in the morning,” he said. But Bama was always quick to emphasize triumph over trial. “The attack has galvanized me. It’s strange in this profession when people are going after you, it’s a sign that you are doing good work.”

Bama believes that ultimately, journalism in Burkina Faso will be protected. “The enemies of the press know that if they kill someone, like what happened with Norbert Zongo, there will be demonstrations and consequences,” he told me. He acknowledged that the amendments to the penal code represent a setback, but he insisted that journalists are not easily quashed. “Now, when you write something, for example, my story on corruption, there were demonstrations and a minister was fired,” he said, of a major story he broke several years ago. “Norbert Zongo didn’t experience that kind of victory.”

When I checked in with Sawadogo shortly after, he was in the midst of finishing an article about a group of some twenty people who said they had fled their village after witnessing a massacre by members of the security forces. They were living in a grim, unfinished building on the outskirts of Ouagadougou. Sawadogo had taken portraits of each person to accompany the piece. The faces were blurred for protection, features barely visible, like the war itself.

On July 8, Human Rights Watch released a report on allegations of the executions of another 180 men around Djibo. On the same day, the United States threatened to withdraw military aid from Burkina. A senior Imam from Djibo went missing and was found dead, and the government in neighboring Mali, where terrorist attacks continue, was overthrown. News of deaths and attacks have been intermittent in the lead up to parliamentary and presidential elections scheduled for November 22. According to the national electoral commission, an estimated 417,000 people from 1,500 villages throughout the country have been unable to register to vote because of the insecurity, raising concerns about the democratic legitimacy of the process.

Sawadogo has since left lefaso.net, citing, in part, security concerns. He now works for Studio Yafa, an NGO-supported radio station. He is anxious about what the future will hold for Burkina Faso, a nation whose great past is overshadowed by ongoing violence. “There are parts of the country that are closed down, there are thousands of children who can’t go to school, they don’t have a future, what are those children going to become tomorrow?” he wondered. “If everyone closes their eyes people will continue to do what they want.” He continued, “This war is equally a war of information”—the only war, perhaps, that Sawadogo thinks is worth fighting.

Reporting for this story was supported by the Fund for Investigative Journalism.

Clair MacDougall is an independent journalist who reports throughout Africa. She is a fellow at the Ira A. Lipman Center for Journalism and Civil and Human Rights at the Columbia Graduate School of Journalism.