“You can’t say ‘hit job’ in here.”

I was six months into my tenure as the editor of the New York Observer, and I was schooling my publisher, Jared Kushner, on why ordering up a slam of someone who had crossed his family in business didn’t pass the journalistic smell test.

Kushner, in an earlier meeting, had asked for a hit piece on an official at Bank of America, and was now in my office to check on how the story was coming together. I had spent the previous weeks trying to avoid the subject with him, knowing full well that the Observer was never going to pursue a story about an anonymous banker whose only sin was running afoul of the Kushner family.

ICYMI: “I spent 45 minutes on the phone with Megyn Kelly asking her to not run that show”

But he was pressing the issue. Finally, in that office meeting in the spring of 2010, I told him the piece was not going to happen, that talk of a “hit job” was a textbook definition of malice, and that I considered the issue closed.

Kushner, then a 28-year-old journalism novice who had so far been deferential to my news judgment, pursed his lips, paused a beat, and ended the conversation.

Thus began the unraveling of my relationship with the man who would become one of the most important advisers to one of the most press-hostile presidents in American history.

A year after that conversation, I would be tossed out, one of five editors at the Observer in the 10 years Kushner served as publisher. My case wasn’t helped when I was quoted in a blog post calling the place a “shitshow” under Kushner and his business-side team.

TRENDING: New York Times makes important statement about mass shootings with a series of clocks

Throughout Donald Trump’s campaign and into his presidency, I have looked back on my short tenure at the Observer for signs of the anti-press fervor I can only assume Kushner has shaped. How did this socially ambitious real-estate developer, who bought a beloved Manhattan weekly and counted Rupert Murdoch as one of his personal heroes, end up helping to guide an administration that has made the vilification of anyone associated with journalism a central plank? Did Kushner simply inherit the “fake news” mantra from his father-in-law, or did he have a hand in creating it? Were there hints during his tenure at the Observer of what was to come?

It didn’t take long at the Observer for me to figure out that Kushner didn’t have much respect for the people on his payroll who were reporters. Several times during my time there, when reporters were due merit raises, I went to him in his office building on Fifth Avenue in Midtown—which he bought at such a premium that he nearly broke the family business—for approval to raise their salaries.

The numbers were tiny, sometimes as little as $3,000 or $4,000 per year. But they meant a lot to the people who were getting them, who often were struggling to stay afloat in New York City. At the time, Kushner and Ivanka Trump were newly married, kidless, and living in an enormous loft apartment in lower Manhattan that had the feel of very fancy corporate digs. I didn’t spot a single family picture or memento, and the fridge was stocked like a college student’s, with cartons of takeout food and little else. When I would approach Kushner about raises for the staff, he would almost always balk, pointing out that if we didn’t boost their pay, there was a line of replacements willing to work for the same salary or less. Journalists, in his mind, were essentially interchangeable, and easily replaceable. The fact that they were so poorly paid was evidence, in his mind, that what they did or how they did it could not possibly be that important. On a couple of occasions, he reversed course, pulling the plug on pay raises he’d approved—and that I’d already let the staffers know were coming. (CJR asked Kushner, through a spokesman, for comment on the issues raised here, and they did not respond.)

I came to believe that Kushner wanted the Observer to succeed not because he believed in what it was, but because he needed it as a bullhorn for his own business interests.

While he was, on the one hand, right—journalism is a notoriously low-paying profession, and there are more willing reporters than there are jobs—his dismissive and even condescending attitude toward the people he had chosen to employ didn’t fit with his emerging public persona as a hip, young progressive Manhattan player. Years later, I would recognize that same disdain for journalists coming from his father-in-law, amplified a thousandfold.

Most weeks, Kushner not only didn’t read the Observer, he didn’t appear to read anything else, either. I never knew him to discuss a book, a play, or anything else that was in the Observer’s cultural wheelhouse. His circle of friends was fairly limited, largely tech executives and other successful business people, a smattering of celebrities, and a coterie of much older successful men, people like Rupert Murdoch, financier Ron Perelman, and the public relations impresario Howard Rubenstein.

Even politics seemed to lie outside his area of interest. Every week, Kushner and I held a conference call with the Observer’s editorial writer, who would pitch ideas for the paper’s two main editorial slots. These ideas usually touched on state, local, or national politics. Kushner almost never showed any interest in what tended, at the time, to be the hottest and most pressing issues of the day.

He bragged that he never read The New York Times, though he did seem to care what was in the New York tabloids and The Wall Street Journal.

ICYMI: Newspapers are using two troublesome words to describe the Las Vegas shooting

At the time, his father-in-law showed a similar cluelessness. Very early in my tenure, I was asked by Kushner to meet with Donald Trump, as a courtesy visit. I went to Trump Tower, navigated the series of outer offices that surround Trump, and met the future president, who was sitting behind his desk, hands folded, in an office completely dominated by framed magazine covers of himself. I had the impression that he had spent a minute composing himself, even posing himself, before I stepped in.

I didn’t entirely know why I was there, and nor, it seemed, did he. He had no words of advice or insights about the Observer or journalism, no thoughts on the news of the day, no story tips. It was clearly a ring-kissing visit, and the fact that I showed up meant the deed was done. “We love Jared,” he repeated, concluding our very short meeting.

While Kushner didn’t remotely care about the content of the paper, he cared desperately that it be seen as a financial success. While that is essentially every publisher’s job, his interest in turning the business side of the Observer around seemed rooted more in bragging rights than in any commitment to the paper itself. He also made it clear that, compared to his day job of buying and selling real estate in New York City, this journalism stuff wasn’t exactly heavy lifting; he treated it as a sort of annoying hobby. (The irony, of course, is that Kushner never was able to replicate the success of Arthur L. Carter, the paper’s founder and previous owner. As for his real-estate success, that has been overshadowed by severe debt problems at his flagship on Fifth Avenue—the building where we’d have our weekly meetings—and some critical stories about rough tactics his company used to force out people who were late in paying their rent.)

You can hear echoes of Kushner’s attitudes toward the press in Trump’s obsession with the “failing” New York Times, a notion that is inaccurate but that echoes Kushner’s singular focus on the Observer’s bottom line, often to the detriment of the quality and integrity of the paper he was supposed to be shepherding.

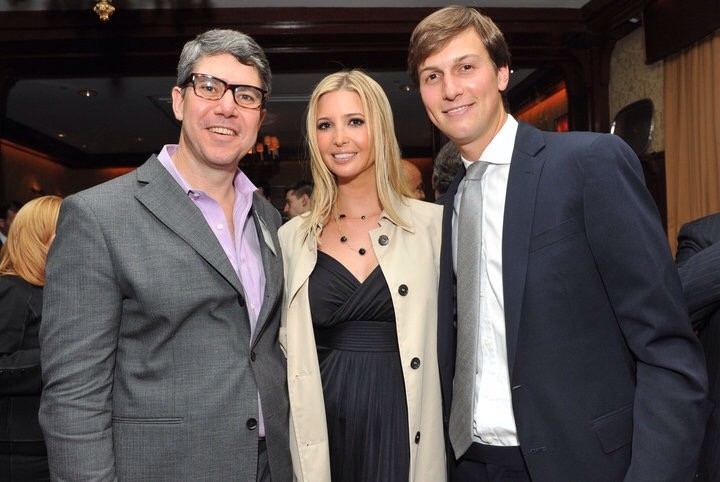

Honeymoon The author, left, with Ivanka Trump and Jared Kushner at an Observer party shortly after he started as editor

I came to believe that Kushner wanted the Observer to succeed not because he believed in what it was, but because he needed it as a bullhorn for his own business interests. The episode with the banker “hit job” was only the most egregious of many more minor examples of him using the paper to prop up himself and his family, ranging from a dubious annual listing of the top people in New York real estate (which was dominated by his clients and business partners) to favorable treatment for other people in his business circle. Other former editors of the paper have weighed in with their own stories about Kushner’s attempts to use the paper to settle scores or reward cronies, including an effort by Kushner to get a critical piece into the Observer about a lender who was taking a tough line in renegotiating debt on the Fifth Avenue tower. The story never ran.

Journalism for him was transactional, an attitude his father-in-law seems to share. “I give you ratings and Web traffic,” Trump seems to fume, “and this is how you treat me?” In the end, Kushner, too, seemed to have decided that he had wrung all he could out of the Observer, and that owning a newspaper with a staff of recalcitrant journalists was more trouble than it was worth. By the time he left the paper, it had given up any pretense of being independent of the Kushner family, or of Donald Trump, and its presence as a feisty independent voice in New York journalism had disappeared.

There’s a deep and complicated family history at play. Given his family’s backstory, it never made sense to me why Kushner owned a newspaper at all. His father, Charles, had been sent to prison for, among other things, trying to coerce his brother-in-law not to cooperate with federal investigators by secretly taping him with a prostitute, then mailing the tape to his sister. The case was a cause célèbre in New Jersey (the US Attorney on the case was Chris Christie), and the family long blamed the press for aiding in Charles Kushner’s downfall.

Jared and his family are extremely close, and it was clear that his father’s travails had a big impact on him. (Charles, whom Jared talked to frequently while the father was imprisoned in Alabama, popped in often during my meetings with Jared on Fifth Avenue. I remember this because Jared would refer to him as “daddy,” which I found strange. I also later learned that Charles was behind the “hit job” story, which explained in retrospect why Jared was so persistent about pursuing it.)

Given this background, why would Jared choose to buy a newspaper, of all things? Was his poor treatment of reporters some sort of revenge for the press’s treatment of his father?

Inside Track President Trump on the phone with King Salman of Saudi Arabia in January, with Jared Kusher and former National Security Adviser Michael Flynn (Mandel Ngan/AFP/Getty Images)

I came to view this family drama as almost Shakespearean, and gave up trying to make sense of why Jared did what he did. But these questions came back to me when I began to see Jared showing up at his father-in-law’s primary rallies around the country, spouting the kind of conservative populist message that I’d never heard come out of Jared’s mouth. When I knew them, Jared and Ivanka were hanging out with Ashton Kutcher and Demi Moore, not trying to keep immigrants out of the country.

Initially, I chalked up his devotion to his father-in-law to family loyalty, a deep and unshakeable trait that runs through both the Kushner and Trump clans, and one that is quite admirable.

But there also was something familiar about the anti-media rants we were hearing from Trump. They brought me back to those two very difficult years at the Observer, and the frustration of working for a paper owned by a man who had no respect for or interest in journalism or the people who practice it. In fact, his view was the opposite, a deep suspicion and derision of journalism and reporters, an impression burned into him by a painful family trauma. In his view, journalism’s utility lay only in what it could do to polish his image or enrich his coffers or those of his family.

And it dawned on me then that Kushner and his father-in-law weren’t so far apart after all. Both had used the media, quite successfully, for their own ends. Now the press had become more trouble than it was worth, and both felt perfectly fine tossing it aside.

It reminds me of a story often told by a writer then working for the Observer, who met Kushner, the man who signed his paycheck, for the first time at a cocktail party. The two of them chit-chatted until Kushner, in mid-conversation, turned and walked away. He had, he told the writer, found someone more important to talk to.

TRENDING: An analysis of Vegas shooting headlines reveals unsettling trends

Kyle Pope was the editor in chief and publisher of the Columbia Journalism Review. He is now executive director of strategic initiatives at Covering Climate Now.