The most dangerous place to be a journalist in America is at a protest.

That’s a key early takeaway from the U.S. Press Freedom Tracker, a nonpartisan website launched in August that documents press freedom incidents around the country. As of mid-September, the database had logged 20 arrests and 21 physical attacks on journalists this year, most of them at public demonstrations.

The Committee to Protect Journalists and the Freedom of the Press Foundation developed the tracker with support from more than two dozen other journalism organizations, including CJR. The tracker collects data points from news stories and tips, and it’s free to use. It’s also needed now more than ever.

ICYMI: A striking detail about NBC’s decision to fire Matt Lauer

With his near-daily denouncements of the press, the president has helped normalize abuses against journalists by ordinary people. Public trust in the press is low, and a growing number of Americans see journalists as part of an elite coastal establishment that doesn’t understand them or share their interests.

Fifteen of the 21 attacks on journalists this year were at protests or rallies, where the victims were targeted because they were journalists.

Those sentiments seem to be combusting at protests. Of the 20 journalists arrested in 2017, six were covering protests against the Dakota Access Pipeline at the Standing Rock reservation in North Dakota; nine more were covering protests at Donald Trump’s inauguration in Washington, DC.

Journalists arrested at protests are usually not charged, or the charges get dropped before trial. But the offenses of which they stand accused tend to be maddeningly vague misdemeanors like “obstruction of a government function.” That’s what filmmaker Jahnny Lee and Mic reporter Jack Smith IV were charged with after their arrests at Standing Rock. They face up to one year in prison. Journalists Aaron Cantú and Alexei Wood, both arrested at DC inauguration protests, were charged with multiple felonies—“inciting a riot” among them—and face decades in prison.

It’s worth underscoring, too, that even if charges aren’t filed or ultimately get dropped, the initial arrest or detainment is still a big deal. They send a chilling message. That’s especially true for the increasing number of freelance and independent journalists who lack institutional legal resources.

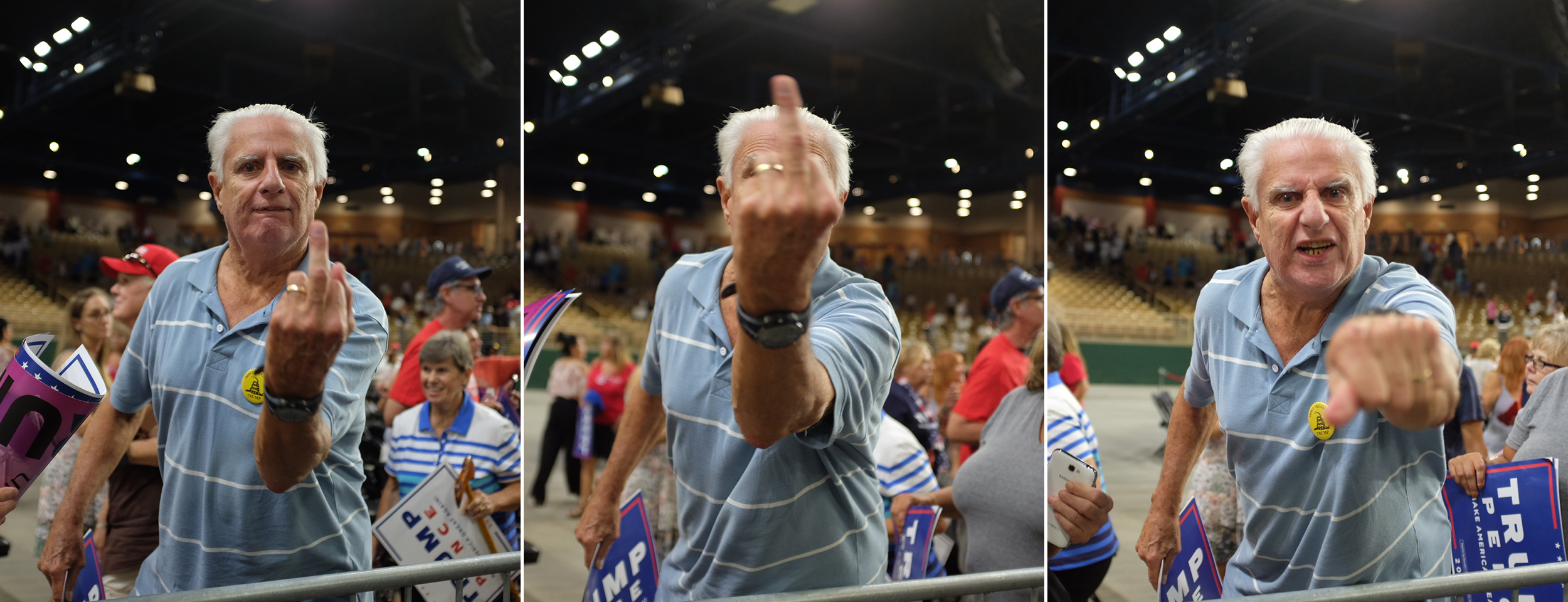

FRIEND OR FOE? A Trump supporter approaches a reporter in Kissimmee, Florida, in August 2016. (Photos by Frank Thorp V/NBC News)

But an arrest or a charge isn’t the only cause for concern—another is a physical attack. Fifteen of the 21 such attacks on journalists this year were at protests or rallies, where the victims were targeted because they were journalists.

Among them was Taylor Lorenz, a reporter for The Hill, who was recording the aftermath of the deadly car attack in Charlottesville when a shirtless man approached and told her to stop. She identified herself as a reporter. He then walked behind her and punched her in the side of the head.

The most serious injury to a reporter that the tracker has documented so far occurred in January at Standing Rock. Independent journalist Jon Ziegler, who streams most of his coverage via YouTube, was recording an aggressive police action against protesters when non-lethal rounds hit his leg and hand. Ziegler was likely known to police because he had been covering Standing Rock for some time. In fact, an officer called out his name before he was shot. A rubber bullet shattered a bone in his finger, requiring emergency reconstructive surgery, a follow-up surgery, and months of physical therapy.

ICYMI: You might’ve seen the Times‘s Weinstein story. But did you miss the bombshell published days after?

This is a critical time for press freedom, and journalists need at least a working understanding of their rights and how to stay safe covering protests. First, journalists have the qualified First Amendment right to record what occurs at protests in public spaces. That includes police activity. On private property, however, or on public property leased to a private party, the owner or tenant may control access to the space and set rules for how it’s used. Journalists are not allowed to trespass to gather news.

Second, journalists don’t need credentials to work in a public space where they have the right to be, but ordinarily it’s smart to display them anyway, because they can convey to police that the journalist is there to cover the protest rather than participate in it. That should discourage police from interfering with the journalist as she gathers news, but that’s not always the case. A press card might actually prompt some officers to target a journalist. In 2011, during the Occupy Wall Street protests, the NYPD used press cards to identify and corral journalists before conducting a mass arrest of protesters in Zuccotti Park, preventing most reporters from documenting it.

Third, journalists have Fourth Amendment protections against unreasonable searches and seizures, and the Supreme Court ruled in 2014 that the police normally may not search a cell phone seized from an arrestee without a warrant. Journalists have extra protections under the Privacy Protection Act, a federal law that requires law enforcement to get a subpoena, instead of a search warrant, to search or seize a journalist’s work product and equipment.

The US has strong legal protections for the press, and we can’t take them for granted. They are under pressure at protests and beyond, and the most effective response is not only to track the threats, but also to develop ways to address them. As Hugo Black, the late Supreme Court justice, wrote in New York Times Co. v. United States, better known as the Pentagon Papers case: “In the First Amendment the Founding Fathers gave the free press the protection it must have to fulfill its essential role in our democracy.”

It’s up to all of us to make sure that protection remains intact.

ICYMI: He was excited to profile a controversial athlete. What happened next? Every journalist’s nightmare.

Peter Sterne and Jonathan Peters are the authors of this story. Peter Sterne is a senior reporter at the Freedom of the Press Foundation and the managing editor of the U.S. Press Freedom Tracker. He was previously a media reporter at Politico. Jonathan Peters is CJR’s press freedom correspondent. He has blogged for the Harvard Law & Policy Review, and has written for Esquire, The Atlantic, Sports Illustrated, Slate, The Nation, Wired, and PBS.