Warren Craghead first drew Donald Trump on July 21, 2016. Trump had just accepted the Republican Party’s presidential nomination, in a speech that described the political leaders he vowed to replace as “a group of censors, critics, and cynics” who would “say anything to keep a rigged system in place.” Watching coverage of the speech on television from his home in Charlottesville, Virginia, Craghead sketched a grotesque portrait on a notecard; in it, Trump appears reptilian, squinty and jowly and unctuous—a bit like a Komodo dragon stuffed into a suit. Later, Craghead scanned the drawing, then posted it to TrumpTrump, his Tumblr account, where he promised a “Donald drawn daily until this nightmare ends.”

Up to the 2016 election, Craghead exclusively drew repulsive portraits of Trump—snarling, naked and leering, then melting into a fetid pool. Following the real Trump’s victory, Craghead’s Trump reconstituted himself. Since then, he has raged on a barren landscape, a bloated monster wearing a crown and clutching a mirror, the ground increasingly littered with debris from four years of havoc.

TrumpTrump now hosts more than 1,500 drawings—one for each day since the nightmare began. Its subjects have grown to include Trump’s appointees and sycophants, along with anthropomorphized rifles and pizza slices, giant skulls and Klansmen, a universe of monsters whose narratives offer a disturbing parallel to the news cycle under the Trump administration. Throughout, Craghead has followed their stories as a sort of beat reporter, pairing each new drawing with a quote or detail encountered in his news consumption, consistently linking to his sources. Reading TrumpTrump, one can see the major storylines of the Trump administration—healthcare and environmental rollbacks, racist and insurrectionist incitement, attacks on the news media—reflected back, grotesque and recognizable.

CJR spoke with Craghead during the final days of the Trump administration. The following excerpts from that conversation have been edited for length and clarity.

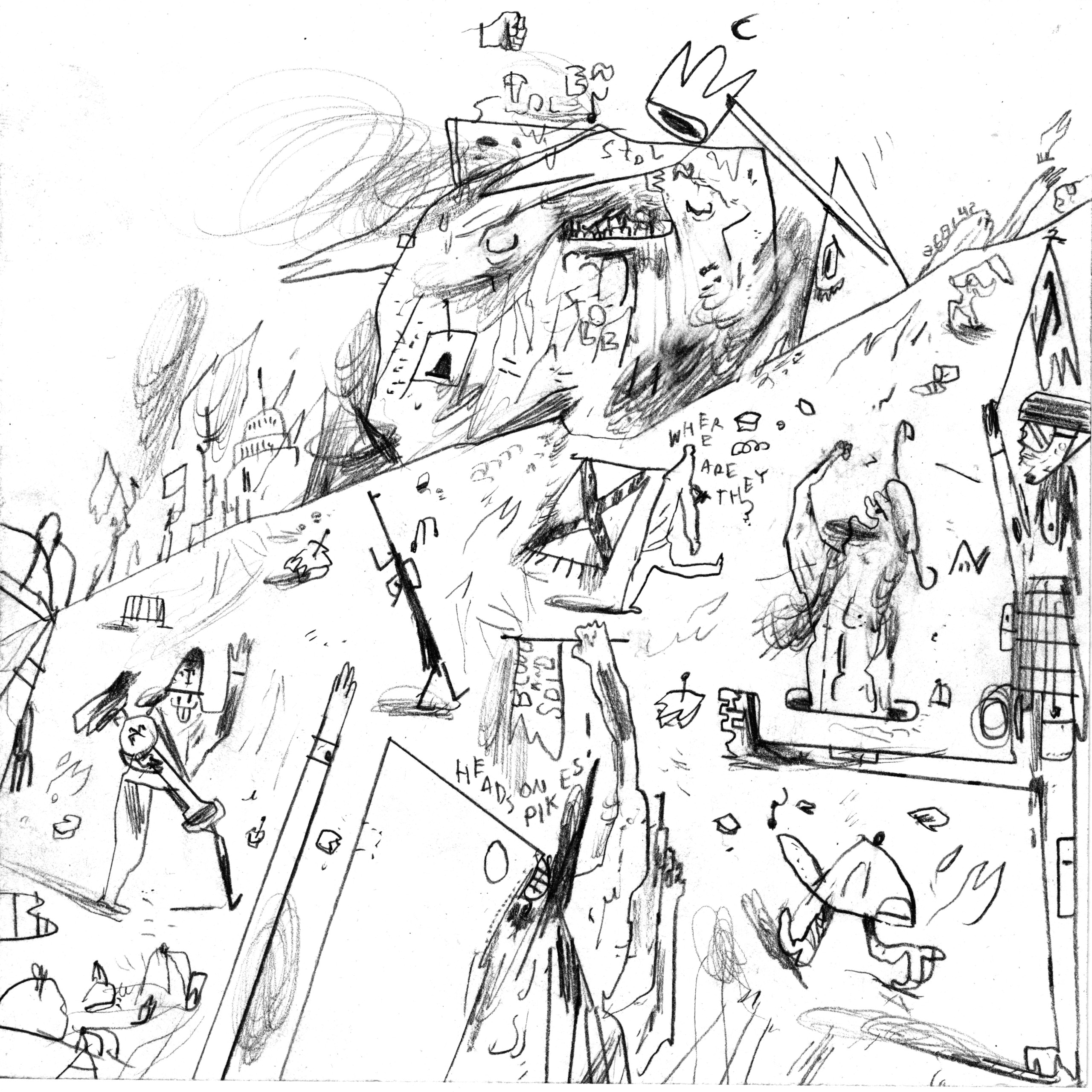

A TrumpTrump drawing posted on January 13, 2021, following the insurrection at the US Capitol. Courtesy of Warren Craghead.

On the evolving phases of TrumpTrump

It began as sort of an offshoot of some earlier projects. I had done LADYH8RS and USAH8RS, both of which were grotesque portraits of misogynist or un-American legislators and other public figures. In 2013, I drew Ken Cuccinelli, who was then the Republican candidate for governor of Virginia, every day for a week, trying to highlight how unfit he was for office. He’s now the acting deputy secretary of homeland security. He has continued to be a great, great, horrible monster.

I drew Trump every day that fall during his campaign. The week before the 2016 election, I drew him melting down into goo. My plan was he was going to lose and then animals were going to come eat the goo and maybe poop it out for a week, until he was just gone. It still would’ve been the longest sustained political-drawing project I’d done.

When Trump won the 2016 election, I remember people saying, Hey, you said you were going to draw this till the nightmare was over. Are you going to? That was my exit ramp. I could have just bailed. But I’m very stubborn.

The way I got out of the melting goo was, he spewed himself forth from his mouth hole. He threw himself up. And then I went on from there.

From November 9, 2016. Courtesy of Warren Craghead.

From there, it changed to another phase. I was looking less at his long history of saying and doing horrible things, and more towards, What’s he going to do to us now? Who is he going to put in charge? I started drawing Pence, drawing DeVos, Steve Bannon, Michael Flynn—all of these people mixed in with him—and writing about who they were and why they were disturbing. I was making drawings very quickly, on note cards.

Then the drawings started becoming more complicated, more elaborate, more focused on documenting things that were happening, like that first summer when they tried to kill Obamacare. I drew on bigger pieces of paper. I would do online searches, find things that were happening, organize the plot in a calendar. So I’d have everything set up for what days I wanted to do things. I drew Paul Ryan. I drew Mitch McConnell as a giant turtle, eating people.

At some point, I realized that Trump is a narcissist, and even bad attention feeds the fire. I was participating in that. And so I thought, Well, what else can I do?

So I started focusing more on his administration’s policies—less of his tweets and the crazy stuff he said, more about rolling back environmental regulations, what they were doing to our education system, who was making money off of what, what taxes were being lowered for the rich. Trump would fall into the background.

I also started drawing the victims of what he did. There was a week that I drew people who had been in the US for decades and were being deported. I drew them with ICE cops and Kirstjen Nielsen and Trump looming in the background. People who’ve been here for thirty, forty years were being deported. Another week, I drew kids who’d been separated from their parents. For a month in the summer of 2019, I drew people who had died in ICE custody.

As I’ve gone along, I feel like I’ve done a better job of not just reacting to whatever chaff Trump has put up, and focusing instead on concrete, material things that are actually happening. Even now, at the end, there are things happening. They’re not wasting a single second.

A drawing of Roxana Hernandez, a transgender woman who died in ICE custody after she was detained at the US border seeking asylum. Courtesy of Warren Craghead.

On linking to his sources

When I started LADYH8RS, one of my friends, a former local journalist, suggested I link to my sources—to give quotes and details more weight, and to make it more of a journalistic project, not just an artistic one. Anyone who argues with the text can click the link and see, Yes, they said this, or, Yes, they sponsored this. So I started doing that. When I got to the Trump project, I did the same thing. Every drawing with writing underneath has a link to where you can find that information.

I did link to a lot of his tweets. It hadn’t occurred to me, when he got kicked off Twitter, how that would affect so many links. A minor thing.

On creating a visual vocabulary

My biggest influence going in was the painter Philip Guston. I don’t only mean his late paintings, which are filled with Klansmen and, later on, some real apocalyptic, cartoony, sort of abstract expressionist imagery. He also did a project called “Poor Richard,” which was about the Nixon administration. He was a hater of Nixon before Watergate broke. He drew Spiro Agnew, Henry Kissinger, all of them—cartoony, grotesque pictures. That was a big influence for me. And by influence, I mean, I stole everything I could, everything that was not nailed down. So the Klansmen in my drawings are obviously from his work.

Over time, my vocabulary began to have little characters that would show up now and then. For example: a pizza slice, because of the “Pizzagate” conspiracy theory from four years ago. The pizza slice shows up all through the project. You’ll see a little pizza slice here and there; it’s been hanging out on Trump, singing to him. I got really good at drawing anthropomorphized M-16 guns walking around. The US Capitol is very tough for me to draw—you think it’s like a cake, but it’s not.

After he was first impeached, I would draw Trump with a little sword sticking out of him. Now he has two swords, of course.

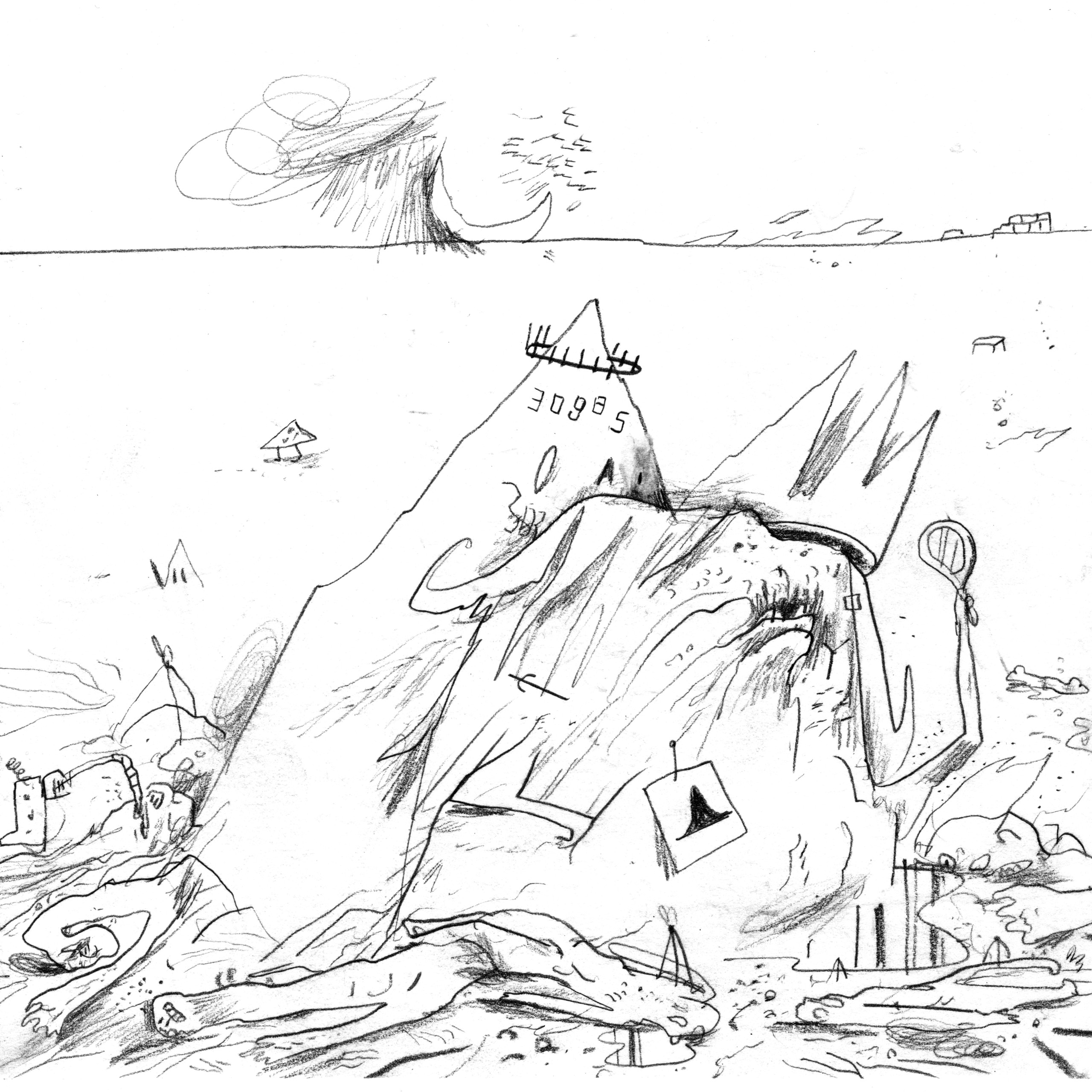

When COVID started becoming an issue, this looming skull appeared in the background, with the number of US deaths on it. The number of course has gone up and up. That character has loomed for a year now.

From April 16, 2020. Deaths in the US attributable to COVID-19 had eclipsed 30,000. Courtesy of Warren Craghead.

Practice as documentation and witnessing

Around 2011, during the Arab Spring, I was drawing a lot of conflict stuff seen through my screen. I know the limitations of doing that, because I’m not there. I don’t know these people and I’m safe at home. I have all of my white privilege in place. I’m totally outside of it.

However, I do think it’s important to try to see what’s happening. For me, drawing is a way to not look away, to not glaze over and move on.

When the protests at Tahrir Square happened, I was very excited and I was very proud to be a person—here was this thing that was almost completely peaceful. I know it hasn’t turned out well for them, but at the time it felt very euphoric.

I started trying to draw less of the historical leaders, and more like, Here are the people on the ground. In 2013, there was a sarin gas attack in Syria that killed a bunch of people, including kids. I was really upset. I searched and found images I wouldn’t have seen otherwise, and I made this book, and the proceeds for it go to the Syrian Children’s Relief Fund.

For my project on the Armenian genocide, as I went through the history, I learned of one day on which 14,000 people were killed in a single town. I thought, I can’t comprehend that number. So I sat down with a bunch of note cards and I drew 14,000 marks. It took me hours. It really brought home for me—in an inadequate, tiny, very weak way—the scale of such a thing.

I think a lot of my work is about trying to not forget things. I draw cartoons about my kids a lot because I want to hold on to these things. I think any parent knows what I’m talking about.

I have some ideas for projects that are happier. I’m going to start one next Wednesday about people doing good things in government: food inspectors, forest rangers. The drawings will be difficult at first because, again, I’m more of a grotesque artist at this point, but I think it’ll be a good road to be on. I like being confused and not knowing what I’m doing. This is a good way to shake that up.

On the relationship between news consumption and drawing

I’ve followed politics pretty closely since the George W. Bush Administration, 9/11, and the Iraq War. I don’t watch cable news because we don’t have cable. I look online to see what’s happening. I get a lot of news from Twitter, which doesn’t always give the brightest take on things, depending on who you follow. I subscribe to the New Yorker.

For TrumpTrump, a lot of days I would just go into my browser, type “Trump administration” into the search box, and see what came up. Sometimes I would find links to local papers, or small magazines, or trade magazines. Then I would find out, Oh yeah, they just changed the oversight rules on nursing homes. That was reported in bigger papers, as well, but I found that in a trade magazine. The internet is a great source because I have access to a wide range of reporting from the local press and journalists in small towns, like Charlottesville, where I live.

From April 19, 2019. Courtesy of Warren Craghead.

On emphasis in journalism and drawing

I have a different metric than them. I’m looking for something relatively short and precise. Although I guess that’s what a lead is, right?

There are times when I’ve cherry-picked things, or left out context to show things in the worst light. I have made a judgment there. But all the drawings come directly from news coverage. In my published books, I list all the source links in an index. Sometimes I’ll even editorialize inside that—he said this because of this. That was actually a lot of work. It would have been much easier for me to just publish a book with the drawings and text on them, but the extra time it took to add in that source material made me really appreciate what journalists do, the fact-checking that goes into things, running down sources and making sure the stuff is done right.

On what was difficult to depict

I live in Charlottesville, Virginia, and we all know what happened there in the summer of 2017. That week, I could not draw Trump. I just couldn’t do it. Anything that I thought of drawing would not capture what happened to all of our friends here. I did go back and draw them, two years later, and it was very raw and tough.

Part of this makes me think of Le Grande Guerre, my World War I live-drawing project. I would draw what happened every day, one-hundred years later. One of the things that project illuminated for me was how long it went on. Maybe that’s part of the Trump project. It’s been a long time. A lot can be done and undone.

August 14, 2017, following the violent white-supremacist rally in Charlottesville, Virginia. Courtesy of Warren Craghead.

On whether to step away

I probably should. There are more than a few people who’ve been worried about my health. Some people think that staring at this stuff and drawing it is corrosive. But it’s not—it’s empowering. It’s no substitute for actual, material activism or advocacy. But it is something; I’m doing something.

If this was just a documentation project, I think that would be wearying. And I have a lot of sympathy for reporters on beats, who are constantly having to just grind out terrible, terrible things. You probably saw that CNN reporter who was upset on the air the other day. But this is not just a documentation project—it’s an art project. I like to draw. I’ll finish a drawing—here’s one from yesterday—and I’ll be like, Oh, I drew that arm with a fist on it really well.

At times it did feel like I was dragging myself through it. But then, other times, it was a delight. You know, Anthony Scaramucci, who was around for like ten days, was great to draw.

On drawing Trump officials

Melania was great to draw—her face is all triangles and lines—but I don’t draw her that often. Jeff Sessions was like a little elf to draw—someone said he looked like a kid who had been cursed by a witch to be an old man. Pompeo is just sort of boring looking. Giuliani is fun to draw.

Pence is great, too—even before the fly incident. That’s something that happened, too: Stuff like the fly would come up, and there were so many good drawings that other people did. I was sort of, All right, I’ve been drawing flies on their heads for a while, I’ll leave that to them. I would see low-hanging fruit and just leave it sometimes. Pence is really good because the way his hair fits to his head is very, very weird. There’s a lot of weird hair on the right, in the US—a lot of strange hair. Matt Gaetz, Giuliani—his hair seemed like it was melting down his face.

On responses to the work

I’ve had a lot of good responses. There have been some people who’ve done some deep dives—RJ Casey for The Comics Journal, F. Stewart-Taylor for Solrad, a roundup at The Atlantic, a cover story by Allan Haverholm in a Swedish art magazine—and I am so grateful for that.

One time, someone told me, Oh, you can’t draw. Ben Garrison is a much better artist than you. My answer to this person was, Hey, that’s great. I’m sorry you don’t like my work, but it’s great you like someone else’s work. You should make sure to let him know.

Brendan Fitzgerald is senior editor of CJR.