Editor’s note: For decades last century, American magazines used beautiful imagery and brave, honest writing to introduce readers to whole new worlds. They invented a visual language, and gave voice to people we’d otherwise never have heard from or seen. This series seeks to celebrate the most interesting examples, and examine the ways they shaped a nation.

The three soldiers lie in a curved line on the sand of New Guinea’s Buna-Gona beach. The man in the foreground, in full uniform, is a few feet from the edge of the sea, his left knee and forearm already buried in sand. We know he is dead; they are all dead. But if we didn’t, the title of the photograph—Dead Americans at Buna Beach, published in the September 20, 1943, edition of Life magazine—removes any ambiguity.

It was the first photograph an American news organization ever ran of US forces killed in action. The photographer, George Strock, embedded with American forces in the South Pacific in December 1942. It was monsoon season, which meant eight to ten inches of rain a day. Entire companies at the front line tested positive for malaria and fought with fevers of 104. The bodies piled up so quickly—nine thousand over two months—that the troops renamed it “Maggot Beach.”

Strock’s thirteen pages of war pictures from the Battle of Buna first ran in Life in February of 1943. But it did not include Dead Americans at Buna Beach. US government censors feared that such a visceral depiction of the human toll of war would break American morale. It wasn’t until September that Life staffers persuaded the censors, and finally President Franklin Roosevelt, to let them publish the photo. Life’s copy read: “To come directly and without words into the presence of their own dead.… This is the reality that lies behind the names that come to rest at last on monuments.” [Content warning: Strock’s photo runs below]

George Strock’s photo of dead US Marines on Papua, New Guineau, during the Pacific War. This was the first photograph to show American war dead during World War 2. George Strock/Getty Images

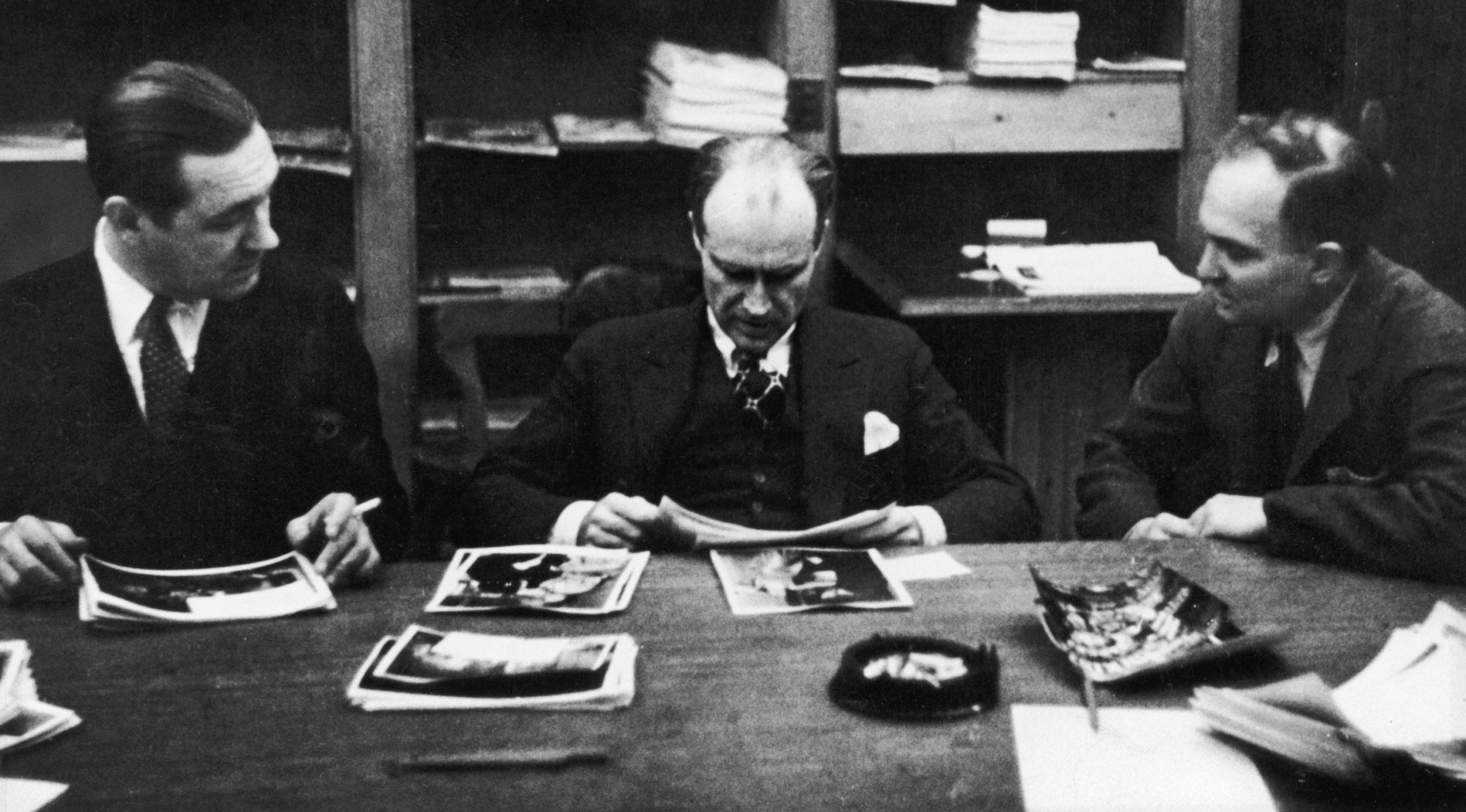

Publisher and editor in chief Henry Luce founded Life in 1936 on the belief that a single picture could alter the course of history. Photojournalism was poised to enter its heyday; the industry’s new 35 mm Leicas and flashbulbs were smaller and lighter. Luce planned to document what he dubbed “the American Century.” Life’s signature element would be the photographic essay, an extended examination of an event or topic driven by what Luce liked to call “beautiful pictures,” with minimal text.

After a tear gas attack by highway patrolmen, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. urges participants of the James Meredith March to stay hopeful and remain non-violent, 1966. Harry Benson/Life magazine. Used with the photographer’s permission.

Access to high-quality images of current events felt brand new. Americans were used to radio broadcasts and newsreels at the movies. Oil-based inks, poor paper, and coarse engraving screens were all outdated by the 1930s; still, major newspapers used them into the 1980s. But Life put out weekly issues with glossy paper and high-quality printing. Luce planned to take new ideas, like journalists embedding with their sources to gather intimate details of their story, mainstream. His first issue, published on November 23, 1936, sold out all 380,000 copies in one day. Four months later, circulation was at 1 million copies a week.

ICYMI: Thirteen seconds. Dozens of bullets. One explosive photo.

By the end of World War II, Life’s staff photographers had grown in number, from four to thirty-eight, and enjoyed near-celebrity status. Access followed. Margaret Bourke-White sat at home with Mohandas Gandhi on a day of silence and photographed him at his spinning wheel. Vietnamese authorities allowed Life’s Larry Burrows to remove a fighter-bomber’s doors, so he could lean out and get the best pictures. Bill Eppridge alone witnessed the vigil of Marilyn Lovell as Mission Control worked to bring her husband, Jim, and the rest of the Apollo 13 crew home alive. Inmates admitted John Shearer inside Attica during the 1971 riots.

The secret was, ‘I’m going to show you something I haven’t seen before.’ The camera cannot lie.

The magazine savored its photographers’ heroics. They were shown harnessed under military helicopters to get the right shot. Captions told how Strock survived an attempted grenade attack and a plane crash to file his negatives of Buna-Gona. In 1953, after Elizabeth II’s coronation, Life chartered a jet and converted it into a darkroom so the team could work the whole way home.

The swagger paid off. Life fixed the best news images the nation had ever seen into America’s collective memory. There was Alfred Eisenstaedt’s V-day nurse and sailor kissing in Times Square; Martha Holmes’s revolutionary picture, published in 1950, of a white fan giggling against the chest of singer Billy Eckstine, who was black; Lennart Nilsson’s groundbreaking 1965 cover photo of an eighteen-week-old human fetus in utero; and Neil Armstrong’s shot on the cover of a 1969 special edition, “To the Moon and Back,” featuring Buzz Aldrin on the surface of the moon, with Armstrong and the Lunar Module Eagle reflected in his visor.

Singer Billy Eckstine and fans. Photo by Martha Holmes/The LIFE Picture Collection via Getty Images

Life also documented regular people, their humanity rendered newsworthy through the photographer’s lens. For “Country Doctor,” published in 1948, W. Eugene Smith embedded with a small-town physician in the Rocky Mountains. America watched Dr. Ernest Ceriani make house calls, cradle an elderly patient on the way to the operating theater, agonize over how to deliver bad news to anxious parents. In “Segregation Story,” published in 1956, Gordon Parks used color photos from quiet moments in the life of an American family in Jim Crow Alabama to educe and channel viewers’ empathy. A young girl and her grandmother stare through a shop window at a crinoline dress on a white-skinned mannequin. A father buys his children ice cream under a sign marked colored.

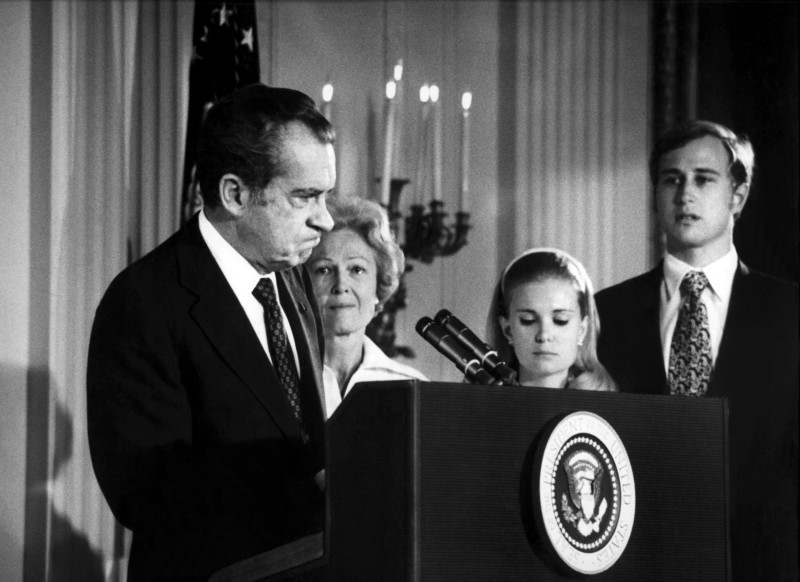

Harry Benson, the Scottish photojournalist, joined Life at the peak of its popularity, in 1969, when circulation was at 8.5 million. Benson, who for years worked as a Fleet Street photographer, shrugs off the heroics the magazine so enjoyed. For Life, Benson photographed KKK meetings; Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s funeral; Nixon in Paris just after his resignation; and the famine in Somalia in the 1980s. Benson embedded with IRA soldiers in Northern Ireland, and photographed the last of the ten paramilitary prisoners to die in the 1981 hunger strike.

Richard Nixon resigns on August 9, 1974, with Pat Nixon, Tricia Nixon Cox, and Edward F. Cox at his side. Harry Benson/Life magazine. Used with the photographer’s permission.

The power of Life’s storytelling, he says, was that readers sensed the honesty in its photos. “It’s really putting a camera in a place you’ve never been before,” he says. “The secret was, ‘I’m going to show you something I haven’t seen before.’ The camera cannot lie.”

“To the Moon and Back” hit newsstands two weeks after the moon landing—a time lapse impossible to imagine in today’s news cycle. Television had been the nation’s dominant medium since the late fifties, and color broadcasts were introduced by the mid-sixties. By 1971 Life had reduced circulation to 7 million; that figure would fall again, to 5.5 million, by 1972. Its last weekly issue went out at the end of that year. Time Inc. published Life special reports, two or three per year, until, in 1978, it revived the magazine as a monthly, which enjoyed moderate success until 2000. Since then Life has existed as a supplement or occasional special issue, such as 2008’s “The American Journey of Barack Obama” or 2016’s “Secrets of the Vatican.”

Even though we have unlimited access to news images today, Benson says, we have failed, so far, to fill the void left by Life. “We used to think that TV would cover everything, but they don’t,” he says. “Fifty images a second is not necessarily good photography.”

ICYMI: A class-action suit has journalists “freaking out”

Amanda Darrach is a contributor to CJR and a visiting scholar at the University of St Andrews School of International Relations. Follow her on Twitter @thedarrach.