Amir Tibon might have predicted that Benjamin Netanyahu, Israel’s prime minister, would eventually be haunted by his meddling with the media. In 2013, Tibon, a young producer, walked into the drab, boxy headquarters of Walla News, in Tel Aviv, to interview for a job as a diplomatic correspondent. Walla, owned by Shaul Elovitch, an Israeli business magnate, was at the time one of the two most read news sites in the country, and was angling to overtake its rival, Ynet, to secure the top spot. “We expect you to go hard after everyone, to not give anyone a break,” Tibon recalls the editor of Walla telling him. Tibon got the job and, for a while, he did go hard, writing stories critical of President Shimon Peres, of ministers for the ruling Likud party, even of Netanyahu. After not very long, however, Tibon learned that there was a subject that had to remain off-limits: Netanyahu’s wife, Sara. He didn’t know why. Nor was he particularly troubled by the prohibition. “It could almost be explained as an editorial argument” to keep the prime minister’s family life private, he says.

But then, Tibon recalls, in 2014, “weird things started to happen.” Stories with no apparent news merit, written by “Walla Staff” and adorned with flattering photos, began featuring prominently on the site: Sara lighting Hanukkah candles with Holocaust survivors, Sara visiting a fire station, Sara’s “fashionable makeover”—with pictures of her posing, hand on hip, in a black dress, followed by photos of Michelle Obama and Jacqueline Kennedy. (Mrs. Netanyahu’s “choice of clothes reflects her new, slim figure,” readers were told.)

By November that year, Netanyahu had sidelined his communications minister and annexed the role for himself—an unheard-of move for an Israeli prime minister. The following January, two months ahead of a national election, a lawsuit by two former employees at the prime minister’s residence alleged that the First Lady had instilled an “atmosphere of fear” there—which the Netanyahus denied. Walla, like all other news outlets, published the former employees’ accounts.

Elovitch saw the story on Walla’s site and fumed. He was the majority shareholder in Bezeq, Israel’s largest telecommunications firm. His company was about $200 million in debt, according to a Justice Ministry document, and he was aggressively pursuing a deal that would merge Bezeq with Yes, a satellite network he owned, for several times Yes’s valuation. But for the merger to go through, he needed approval from the communications minister—in other words, from Netanyahu. Upon reading the article, Elovitch sent a text message to Ilan Yeshua, Walla’s CEO: “Take it off immediately, it will ruin the Yes approval. . .I’ll kill you.”

Yeshua complied. Almost as soon as the story was posted, it disappeared from Walla entirely. A reader who had the story open before it vanished would find a message in its stead: page not found.

Now it was the journalists’ turn to fume. A group marched up to Yeshua’s office and threatened to resign. “We felt that we were losing control of our journalistic independence,” Tibon recalls. Several filed complaints with the Union of Journalists in Israel about apparent conflicts of interest in the newsroom. “We knew that Walla was protecting Netanyahu,” Yair Tarchitsky, who heads the union, says. “We saw what Elovitch was giving—but we didn’t know what he was getting in return.”

The merger—which was successful, delivering Elovitch tens of millions of dollars, according to Avichai Mandelblit, Israel’s attorney general—is now the centerpiece of what’s known as “Case 4000,” the most serious of three major corruption cases brought against Netanyahu in February, only weeks before his recent bid for reelection. Mandelblit announced that the prime minister would be indicted for bribery, fraud, and breach of trust, pending a hearing. (He also said that he would indict Elovitch and Elovitch’s wife for bribery and obstruction of justice.) Three former Netanyahu aides—including Nir Hefetz, Netanyahu’s media adviser and right-hand man—have turned state’s witness.

Another case against Netanyahu—“Case 2000”—likewise concerns the media, alleging that Netanyahu offered Arnon “Noni” Mozes, the publisher of Yediot Ahronot, a deal to curb the circulation of Israel Hayom, its main competitor, in return for favorable coverage about him in Yediot and “help” in his election, an arrangement that never came to fruition. Netanyahu denies any wrongdoing and argues that Mandelblit’s indictment is not formal until he gets a fair hearing, which he managed to delay until October.

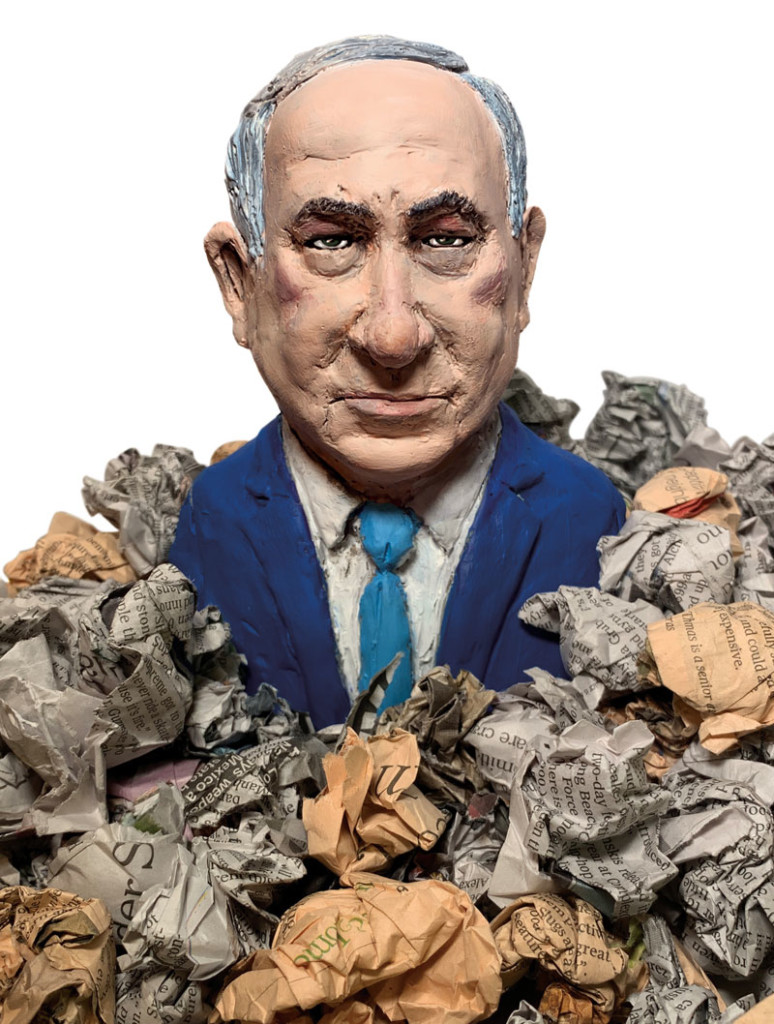

But when the charges were announced, it was the first time since Netanyahu’s ascent that his power fell into doubt. For the past decade, most Israelis were willing to overlook the man’s transgressions. Even Netanyahu’s detractors had come to consider his rule an inevitability; his job has no term limits. Now it became impossible to ignore that no Israeli leader has ever before served under indictment—a fact that Netanyahu exploited in the months following Mandelblit’s announcement to inveigh against a “witch hunt” orchestrated by a “leftist media” eager to overthrow him. In these diatribes, rarely did Netanyahu mention Mandelblit by name—perhaps because, as Netanyahu knew well, to accuse his attorney general of a covert leftist agenda would be a stretch: Mandelblit was his own appointee, a former cabinet secretary and a kippah-wearing jurist who is widely respected across the political spectrum.

Netanyahu’s defensive ploys almost worked. In April, he won reelection. But his vulnerability showed, and after little more than a month, he failed to form a coalition in his government within the 42 days allotted by Israeli law. In an unprecedented turn of events, Netanyahu would be forced to face Israeli voters again, on September 17. “We’ll run a sharp, clear election campaign which will bring us victory,” he told reporters. “We’ll win and the public will win.”

Until this point, Netanyahu’s role as communications minister had seemed to cement his power. The position enabled him to commandeer every regulatory decision having to do with Israel’s bustling telecommunications sector—television broadcasters, cell phone providers, internet start-ups—as well as its infrastructure. In a country where owners of media companies tend to be big players in other major industries (real estate, insurance, oil and gas), control of the Communications Ministry also meant authority over Israel’s main financial power brokers. Mandelblit’s charges, however, highlighted the paradox that has resulted from Netanyahu’s unlikely setup: a story of government intervention, manipulation, and moneyed interests on the one hand, but also one of a vigorous, challenging, and confrontational press on the other—as one veteran journalist described it to me, a “biting” press. (In particular, Gidi Weitz, a reporter for Haaretz, was instrumental in unveiling the story of Walla.) Netanyahu has, perhaps to his ruin, built himself into the media’s omnipresent foil. Among analysts of Israeli politics, the most common word used to describe Netanyahu’s view of the press is “obsession.”

The Israeli press didn’t start out independent. For years, party membership governed almost every aspect of a person’s life: where she worked, what school her children went to, which paper she read in the morning. Hebrew-language newspapers have been in existence since before the country’s founding, in 1948, and were mostly funded by political parties or ideological organizations, which also dictated their coverage. Editors in Israel’s early years considered it their primary responsibility to “educate” the public, rather than to hold the powerful to account. In many ways, they were the country’s powerful. An influential institution called the Editors Committee facilitated exchanges between the government and the press, essentially encouraging self-censorship. Things went on that way until the late 1960s, when Israel’s public broadcaster began to fill the role of establishment news and the status of party-affiliated newspapers eroded. Later, during a surprise attack by Arab countries, which led to the Yom Kippur War, in 1973, the Editors Committee drew harsh criticism for knowing about Israel’s lack of preparedness and censoring reports on it. By the late 1980s Israel’s party newspapers began shuttering; later, commercial television upended the landscape of broadcast news.

“And that’s when Netanyahu shows up on the stage,” says Tehilla Shwartz Altshuler, who heads the Media Reform Program at the Israel Democracy Institute. Netanyahu, who had spent much of his childhood in Philadelphia and his post-military years at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, served for four years as Israel’s ambassador to the United Nations, in New York. He returned to Israel in 1988, fluent not only in English but also in American media culture. Observers recall him shuttling between Likud primary events carrying a rack of identical blue shirts—changing every few hours to avoid the appearance of perspiration on camera. He knew how to apply his own makeup. This, in a country where politicians were known for their sabra unkemptness.

Netanyahu “was a master of television,” Shwartz Altshuler says. He brought ratings and intrigue to a lackluster news environment, and was rewarded with fawning prime-time coverage. (“To what do we owe the pleasure of your visit to Israel?” began a typical interview with Israel’s public broadcaster.)

But a succession of events punctured that mutually beneficial relationship. In 1993, Netanyahu stunned Israelis when he voluntarily went on air to announce that an illicit tape of him having sex with a woman other than his wife was being used as extortion to keep him from running for the Likud leadership. He seemed to have expected the media to adopt his sense of outrage and zero in on his alleged blackmailer—who he all but stated was his political rival. Instead, details about the affair and the woman in question dominated the headlines for weeks. Netanyahu went on to win the primary, but “he was stung,” says Anshel Pfeffer, author of the biography Bibi: The Turbulent Life and Times of Benjamin Netanyahu (2018). “He felt that he was the victim.” Then came the Oslo Accords. The Israeli and international press breathlessly covered the historic peace agreement between Israeli prime minister Yitzhak Rabin and Palestinian leader Yasir Arafat, which culminated in a three-way Nobel Peace Prize, also shared with Shimon Peres. Netanyahu, the leader of the opposition at the time, vehemently opposed the deal, and was treated dismissively by the media, Pfeffer says: “The only game in town was Oslo.”

The relationship between Netanyahu and the press reached its nadir in the aftermath of Rabin’s assassination, by a Jewish extremist, in 1995, and with the triumph of Netanyahu over Peres in the election for prime minister the following year. About a month before the murder, Netanyahu stood smiling from a balcony during a rally as throngs of protesters chanted “Death to Rabin.” Journalists never let Netanyahu forget it, writing about an atmosphere of incitement and intimidation they tied directly to the assassination. “He was seen almost as a usurper,” Natan Sachs, the director of the Brookings Institution’s Center for Middle East Policy, says.

“If you look at what happened, the relationship never recovered,” Pfeffer tells me. “In 1996, it was very clear that the media was rooting for Peres and expecting him to win. When Netanyahu won, the sense was that the media was screwed. You could argue that that’s been the dynamic ever since.”

In 2015, after Walla made the Sara Netanyahu story disappear, word got leaked to Ynet, which sent a push notification to its readers, alerting them to the news. Thoroughly embarrassed, Walla management changed course. Editors no longer emptied internet pages of content in a way that could be traced. “The damage in deleting a piece is great and everyone understood that, because Google remembers everything,” Avner Borochov, an editor at Walla, told HaMakor, an investigative program. Instead, editors shifted to what they termed “burying” or “downgrading” stories that were deemed unflattering to the prime minister and his family. Such was the case, for example, with two articles detailing the lawsuit brought by a former housekeeper, who won $44,000 in damages from the Netanyahus. (“Keep downgrading it fast,” Elovitch texted Yeshua, according to the attorney general’s charge sheet.)

Around the same time, according to Mandelblit, despite warnings from several career professionals in the Communications Ministry that the Bezeq-Yes merger would violate antitrust laws, Netanyahu signed a letter crucial to advancing the deal. Netanyahu has disputed this charge: “The claim that I acted for the benefit of Bezeq at the expense of professional considerations is simply and fundamentally baseless.” But after Netanyahu’s boost to the merger, Hefetz, Netanyahu’s media adviser, ordered Yeshua to post several stories, including one praising Netanyahu’s intention to speak in front of the US Congress and another disputing accusations of financial irregularities at the prime minister’s residence; he also demanded that Walla stop livestreaming a left-wing rally called “Just Not Bibi.”

Yeshua went along with all those demands. Under pressure, he also reportedly sent Hefetz an interview that Walla had recorded with the prime minister ahead of that year’s election. He texted Hefetz: “You never got this from me!” Hefetz sent back a heavily edited version of the interview and texted Yeshua: “Of course not. . .If someone says something—we’ll coordinate an answer.”

The dance carried on through Election Day that March, when polls showed Netanyahu’s Likud party trailing the center-left Zionist Camp by three to four seats. Netanyahu saw the numbers and panicked. (Hefetz made Yeshua change the wording of Walla’s headline to “worried,” explaining in a text, “Panicked is negative.”)

No Israeli leader has ever served under indictment—a fact that Netanyahu has exploited to inveigh against a “witch hunt” orchestrated by a “leftist media” eager to overthrow him.

At 12:23 in the afternoon on Election Day, a video appeared on the prime minister’s Facebook account. Set against a map of the Middle East and the Israeli flag, it depicted Netanyahu, in extreme close-up, speaking in a tone usually reserved for denouncing terror attacks. “Arab voters are coming out in droves to the ballot boxes,” he said. “Left-wing NGOs are busing them in.” Israeli media outlets refrained from showing the video: to display it would violate the country’s strict election campaign laws. Walla, however, featured the video as the lead story on its homepage, where it stayed for hours.

Shortly after the video was posted, Yeshua’s phone dinged. A text message from Hefetz came in: “I showed Bibi the lead—he’s happy.” The following morning, against all previous predictions, Netanyahu was declared the victor of the election for prime minister.

In late December 2016, news broke that police were investigating potential criminal behavior by Netanyahu and two businessmen whose identities were not revealed. Late the next night, Elovitch urgently summoned Yeshua to his house, in north Tel Aviv. Hefetz had reportedly already visited Elovitch earlier that evening, warning him that one of the investigations may have to do with the contact between him and the prime minister. According to detailed reporting in Haaretz, Elovitch asked Yeshua to promise that he would tell investigators that all decisions regarding coverage at Walla were made solely by him—Yeshua—and that Elovitch had never intervened in matters of editorial content. Elovitch further told Yeshua that he and Hefetz had agreed to delete all their previous correspondence from their phones. According to Haaretz, and corroborated for this report by a source familiar with the events, Hefetz ordered Yeshua: “Throw your phone into the toilet.”

Yeshua demurred. He told Elovitch that he had photos of his children saved to his phone and needed time to transfer them. He would destroy the phone the following day, he said. He never did.

In retrospect, Elovitch’s fear had been misplaced: the two businessmen at the heart of the pending investigations turned out to have been Noni Mozes, the Yediot publisher, and Arnon Milchan, a Hollywood producer. In fact, Elovitch’s order only backfired: Yeshua now made sure that his entire message history remained intact; when the time came, the source familiar with the events says, he turned over evidence to investigators that would lead to the attorney general’s decision to indict Elovitch and Netanyahu.

Mandelblit’s charge sheet, written as a public letter to Netanyahu, makes for a chilling read. Over 57 pages, it details how, almost daily, associates of the prime minister texted Yeshua, pressuring him to alter coverage to better suit the prime minister. “Elovitch made sure that Walla gave you and your wife unusual access and material influence over the site’s content,” Mandelblit wrote to Netanyahu. “Your intensive demands and the Elovitches’ unusual response to those demands amounted to a steamroller on the editors and reporters.”

The similarities between the Robert Mueller investigation in the US and the Mandelblit investigation in Israel are evident: both lasted for two years, targeted the occupant of the highest office in the land, and were carried out by muted, straitlaced attorneys in environments that were anything but. There was an important difference, however: whereas the Mueller report’s release truly made waves, Mandelblit’s announcement of charges was hardly surprising; there had been leaks about the exact indictments Netanyahu would face weeks before they were declared. Still, the news dominated front-page coverage for several days. (“A Classic Thriller,” Haaretz called the charge sheet. “Two years of intensive inquests,” Channel 12 began its broadcast, “and an unfortunate bottom line.”) The timing was bad for Netanyahu: polls showed that the newly formed centrist Blue and White party, headed by Benny Gantz, former chief of staff for the Israel Defense Forces, held a decisive lead in the race for prime minister. A third of the public said that Netanyahu should resign immediately.

Netanyahu’s antagonistic relationship with the media has rendered him suspicious, defensive, closed off.

Yet most Israelis did not parse Mandelblit’s damning document. Instead, they watched Netanyahu go on the air, at prime time, on the eve of Mandelblit’s announcement, and reduce it to a trifle. “They’re talking about two and a half articles in Walla, out of an ocean—not a sea—an ocean of hostile articles against me.” He went on: “Who is the first person in history to be accused of bribery for positive coverage? Me, Benjamin Netanyahu. The most maligned person in the history of Israeli media.”

By playing the victim, Netanyahu was soon able to gain back his base. For several weeks, drivers passing by the busy Glilot intersection north of Tel Aviv saw not the usual campaign posters depicting candidates’ Photoshopped portraits, but a billboard showing four stern faces: Ben Caspit, Amnon Abramovitch, Guy Peleg, and Raviv Drucker—all of them journalists who had been reporting critically on the prime minister. A line of text ran above their faces: “They will not decide. You decide.”

By all accounts, the job of covering Netanyahu has become more difficult with time. His antagonistic relationship with the media has rendered him suspicious, defensive, closed off. He rebukes journalists by name, which many see as a direct imitation of Donald Trump, with whom Netanyahu shares an especially cozy alliance and a number of career parallels. Denigrations of “fake news” pepper his speeches. Reporters also recognize a growing disregard for the truth. “He used to have statesmanlike boundaries,” says Tal Shalev, who has been covering Netanyahu since 2011 for a string of publications. “But in the past two or three years, statements coming out of the prime minister’s bureau have turned out to be either not true or distorted; it’s very Trumpian.” Add to that Netanyahu’s mounting legal woes, she says, and “You are reminded that this is a man who is out to save his own skin.”

Another difficulty for journalists lies in the fact that Netanyahu has found ways to circumvent them. In 1999, he experienced his first and only election loss, to Labor’s Ehud Barak. Netanyahu regarded his defeat as a travesty tied directly to negative coverage, particularly by Yediot. He told his associates, “I need my own media.” In stepped his friend Ronald Lauder, the American cosmetics tycoon, who bought a majority stake in Israel’s Channel 10. But, as Pfeffer explains, that “couldn’t stop journalists at Channel 10 from covering him critically.”

More significant for Netanyahu was the founding, in 2007, of Israel Hayom, a free tabloid, by Sheldon Adelson, the US casino mogul who had been his longtime benefactor. Israel Hayom’s launch drastically changed the media landscape. For the first time, Netanyahu had a megaphone for his views. Just as important, the paper saw its role as draining the resources of other news outlets, Pfeffer says: “Otherwise why make a newspaper for free?”

The ploy worked. Mozes, in particular, felt the financial pressure. “His hostility toward Bibi spiked when Adelson came in,” Michael Brizon, who had been a columnist at Yediot for 15 years and writes under the pen name B. Michael, tells me. The nature of reporting changed, too. “Israel Hayom created a new strategy of pulling the curtain back and of telling readers, ‘Here’s what you won’t see in Yediot,’ ” Shwartz Altshuler says. “Until then, media outlets ignored each other. Israel Hayom put the whole industry into a spin. Suddenly Yediot had to answer and to attack Israel Hayom. And Haaretz got in, too. Newspapers suddenly became not just reporters of the news but critics of the news.”

Israel Hayom has become the most widely read daily in Israel, but it never won the establishment cachet of newspapers like Yediot, Maariv, or Haaretz that Netanyahu so craved. What’s more, he remained fixated on his negative coverage, writing a furious op-ed and a series of Facebook posts excoriating pundits who’d criticized him. “The leftist media is on a Bolshevik witch hunt and is engaged in brainwashing and character assassination against my family and myself,” he said in 2017. And so, for the past four years, leading up to the recent election, Netanyahu has refused to sit for a television interview with any network at all, except for a little-known outlet called “the Heritage Channel,” or Channel 20.

When Channel 20 began broadcasting, in 2014, its license was for educational programming, but its ambition was on a far grander scale: the station applied for a permit to broadcast news, and saw itself as an Israeli version of Fox News—with a clear conservative agenda and even a similar motto: “Really Balanced Television.” Its owners wanted to enter “the big league,” as Shwartz Altshuler explains. Over the next three years, Channel 20 aired news and covered right-wing rallies, getting fined more than $100,000 by the Council for Cable Television and Satellite Broadcasting for breaching the terms of its license. In 2017, when a key witness in Case 4000 was arrested, Netanyahu invited two journalists from Channel 20 to his residence shortly before midnight and granted them an exclusive interview—once again breaking the rules. This was the height of irony: breaching regulation by interviewing the regulator. Behind the scenes, lawmakers from the ruling Likud party began working in Knesset committees to change Channel 20’s designation; last year, its license was expanded to include news, politics, and entertainment.

But despite the exclusive interviews and government backing, Channel 20 continues to flail, averaging only 1.1 percent ratings among Jewish households for its nightly news broadcast (compared with 11 percent and 8 percent, respectively, for the more established networks, Channel 12 and Channel 13). In February, with Netanyahu embroiled in scandal, his party launched “Likud TV”—a daily online blend of filtered news and sycophantic material. Broadcasts felt farcical. “To celebrate International Women’s Day, we ask you, women, to tell us how Benjamin Netanyahu has helped or impacted your life,” one began. Likud TV made a habit of reposting videos from Netanyahu’s Facebook account, where he has 2.4 million followers. That might not sound like much compared with Trump’s social-media clout, but the number represents more than a quarter of the Israeli population. By simultaneously shunning the mainstream media and providing it with endless fodder through his own outlets, Netanyahu managed to steer the public conversation away from the Mandelblit story, just in time for Election Day.

In March, unsubstantiated rumors began to surface about Gantz, Netanyahu’s opponent. That he was mentally unstable. That he had been wiretapped by Iran. That he had had an extramarital affair. That he had (God forbid) visited a therapist. Likud TV amplified the gossip, creating a smoke screen. Netanyahu convened a press conference that only served to fan the flames. “Benny Gantz, what do the Iranians have on you that you are hiding from the Israeli public?” he taunted.

When voters went to the polls, in April, Netanyahu repeated his winning strategy from 2015. Deploying his “Arabs are coming out in droves” tone, with the same map and flag in the background, he once again appeared on Facebook and warned that the Left was on its way to victory with help from the Arab vote. (Never mind that Arab turnout would prove to be among the lowest it had been in years.) He called his barrage of videos on Facebook an “emergency livestream.” This time around, however, his messaging wasn’t picked up by Walla.

Netanyahu’s bedeviling of the press has been effective: according to a recent survey by Doron Navot, a Haifa University scholar of political corruption, 77 percent of Likud voters believe that the media is unfair. What’s more, almost 90 percent of religious and ultra-Orthodox Israelis say that the media in Israel has been attempting to overthrow Netanyahu. By contrast, 87 percent of the leftist Labor party thinks that the media is fair. The media has become a fault line between two diverging Israeli realities. Navot tells me that journalism is “perceived as the opposition”; Udi Segal, chief political analyst at Channel 13, has said that the media is “the bloody steak that Netanyahu serves his electorate.”

On April 9, Netanyahu won a fourth term in office. Despite an impressive showing for Gantz’s centrist party, Israelis handed a decisive victory to the right-wing bloc, which was aided by Netanyahu’s last-minute pronouncement that, if he were reelected, Israel would begin to annex the West Bank. Analysts believed that the victory paved the way for Netanyahu to make a deal: annexation or expansion of Israeli settlements in exchange for unflagging support of him in his future legal battles. But once Netanyahu set to work, he found himself unable to negotiate terms between the ultra-Orthodox and the secular, Russian-émigré wings of his party. Officially, the deadlock had to do with squabbles over a military exemption law. Yet behind the scenes Netanyahu’s legal problems were on full display; his position entering coalition talks was so weak that other parties became intractable in their demands. Israeli politics is now at a standstill. No bills are expected to pass until after the next election, in the fall, when the country will be thrown into further disarray by Netanyahu’s hearing before Mandelblit.

For Israeli journalists covering the prime minister, work continues apace—with the recognition that they have been undermined. “Benjamin Netanyahu has managed to annihilate the concept of ‘truth,’ ” Drucker, one of the investigative reporters targeted by Netanyahu, wrote on his blog. “He shattered the institutions that were once part of the consensus and dressed up all the journalists in partisan shirts.” Even so, Netanyahu may pay the ultimate price for this. Yossi Verter, a veteran political analyst for Haaretz, wrote that, once the coalition negotiations broke down, “the countdown to the end of the Netanyahu era began.”

In the months until the next election, and the Netanyahu hearing that will follow, the war over public opinion will only intensify. Netanyahu had hoped that a decisive election victory would force his coalition partners to rally around him and secure him immunity from prosecution. That has now ended. He enters yet another campaign season as a prime minister unable to govern. The prevailing assumption among legal experts is that Mandelblit is not likely to waver; the charge sheet will be made into an official indictment.

Navot argues that what’s at stake is not only Netanyahu’s position, but the fate of Israeli democracy itself. “He tries to present this as a personal war against him, but it’s not. It’s a war about the character of Israel, where on one side you have serious journalists who do real work, and on the other side you have”—he pauses for a moment—“him.”

Ruth Margalit is an Israeli writer. Her writing has appeared in The New Yorker, the New York Times Magazine, and the New York Review of Books. Follow her on Twitter @ruthmargalit.