In March, Anna Wintour, the editor in chief of Vogue and global content adviser at Condé Nast, selected Alexi McCammond, a twenty-seven-year-old political reporter for Axios, the Beltway-insider publication known for covering the news in bullet points, to run Teen Vogue. The hire was controversial; soon after it was announced, readers began circulating anti-Asian and homophobic tweets that McCammond had posted when she was seventeen. It was also a surprise to the magazine’s staff, who suddenly found themselves fielding online blowback to McCammond. Many were frustrated that they had not been given a heads-up about her appointment, and found McCammond—who had no magazine experience and was dating someone from the Joe Biden administration—a confusing pick to lead Teen Vogue, which, alongside celebrity-fashion photography, runs rabble-rousing articles claiming that Biden and the Democrats represent a “ruling class.” Lindsay Peoples Wagner, the outgoing editor, had not included McCammond among her list of potential successors, and she cautioned Condé Nast that the tweets might pose a problem. Soon, a rumor went around, one that aimed to explain how Wintour had arrived at McCammond in the first place: perhaps, it was suggested, she’d sought recommendations from Biden.

It may come as little surprise that no one was able to confirm whether the gossip was true. (Wintour declined to comment. A Condé Nast spokesperson said, “It was a rumor that ran around last spring and is totally false.”) But like all good rumors, it was extraordinary only in its banality; the fact that it was believable was telling. Wintour—who has hosted fundraisers for Biden and Barack Obama, and whose daughter-in-law worked for the Biden campaign—might have had the access and, conceivably, the inclination to turn to Biden for advice on personnel. And yet the notion of a referral from the president-elect posed a stark ideological conflict with the antiestablishment sensibility of Teen Vogue. As the backlash to McCammond exploded, and Condé Nast failed to assuage the public or employees, the magazine’s staff took steps to distance themselves from their new boss. On Twitter, they published a note condemning her offensive statements. Drafting the message was an exercise in both collective action and anxious restraint: “One thing that got lost in those edits,” a staffer told me, “was that this is about Condé management and our concerns as to what they think Teen Vogue is and what it means to lead a publication like this.”

The question of what Teen Vogue is has become the basis of escalating conflict in-house as, over the years, the magazine has changed considerably. When it entered the scene, in 2003, Teen Vogue was conceived as a high-fashion alternative to Seventeen and CosmoGirl, an outlet for aspiring upper-class socialites featuring mostly white, thin celebrities like Mischa Barton, Mandy Moore, and Ivanka Trump. The audience skewed more toward college-age readers than young teens. Amy Astley, the founding editor, said upon its debut, “We are going to do what we do well, which is fashion, beauty, and style.” Kara Jesella, the magazine’s first beauty editor, told me recently that Teen Vogue strove to be apolitical: “We were trying to make the content not not feminist. That was about the extent of the kind of activism we were doing.”

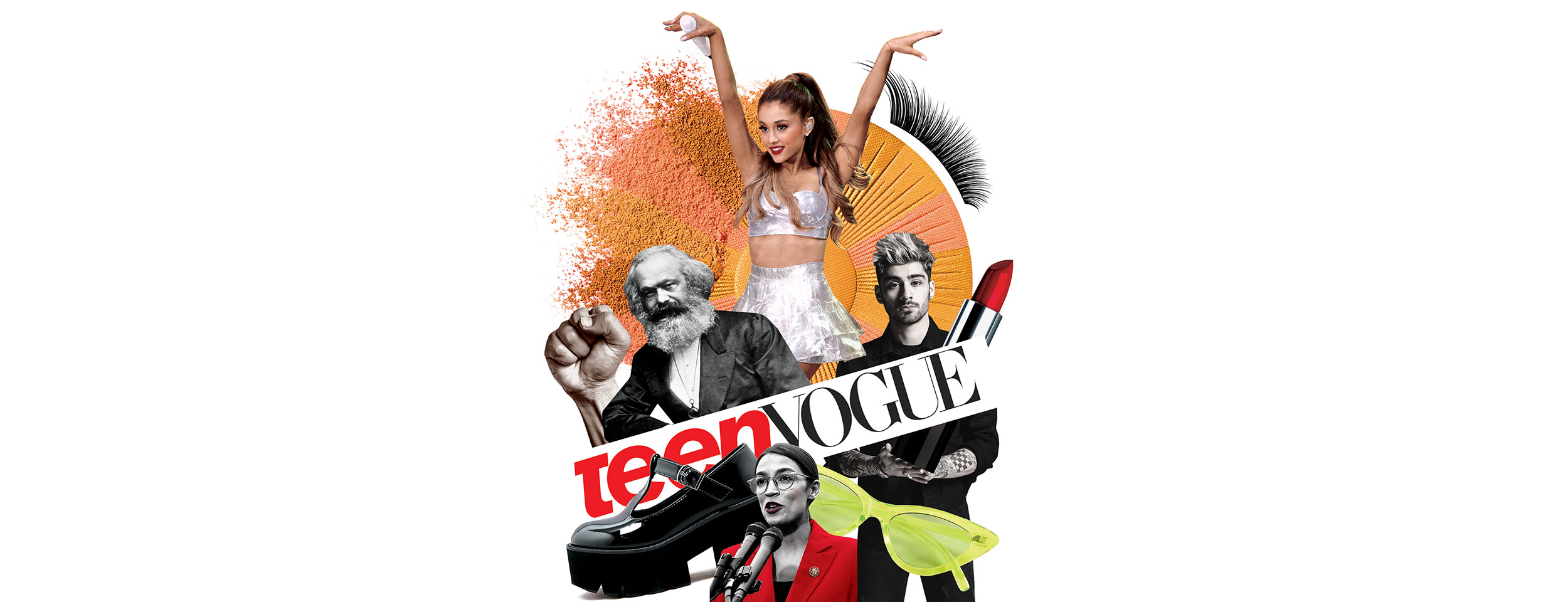

Since then, Teen Vogue has retained its passion for style, but transformed into a charmingly unholy, strangely coherent mix of explainers on Karl Marx, op-eds calling for prison abolition, and on-the-ground protest coverage from teens—all of which sit beside profiles of Jari Jones, a transgender model; a guide to oral sex; and the latest on Zayn Malik and Gigi Hadid. It’s a curious evolution for a publication within Condé Nast, a media conglomerate better known for being an institution of power than for challenging it. The contradictions are obvious: Teen Vogue maintains a socialist bent while trying to commodify its brand for advertisers primarily in the fashion and beauty industry. Yet its peculiar position in media has seemed, somehow, to work; the magazine has attracted bona fide leftists to its ranks as well as praise from unlikely admirers. In 2019, Jacobin, the socialist publication, ran a piece that declared: “Teen Vogue Is Good.”

Not everyone reads Teen Vogue—its website averages roughly seven million monthly unique views—yet it seems as if everyone has an opinion on it. The McCammond debacle proved no exception. Within a week, Ulta Beauty suspended an advertising campaign with Teen Vogue; McCammond, who would have been the magazine’s third Black editor in chief, was caught in a high-profile disaster. She apologized for her old tweets and announced her resignation before having started her first day. (“After speaking with Alexi this morning, we agreed that it was best to part ways, so as to not overshadow the important work happening at Teen Vogue,” Stan Duncan, Condé’s chief people officer, wrote in an email to the company.) The staff were rattled; they were soon inscribed into a narrative—first within right-wing media, then more broadly—of having organized to push McCammond out, despite the fact that they had no say in her hiring or departure. It was, critics claimed, an example of cancel culture run amok. People well outside of Teen Vogue’s demographic threatened to cancel their subscriptions.

The anxieties that Teen Vogue seems to awaken in the general public have proved to be analogous to how America sees teen girls, so frequently flattened into either Greta Thunberg–like saviors or overly woke children who need to be saved. Even when the response is praise, the tone tends to be patronizing. “I do think women’s media is often looked down upon in terms of politics, and that only gets further magnified when you add the teen girl to it,” Samhita Mukhopadhyay, a former executive editor of Teen Vogue, said. “It’s our constant denigration of young women and their ability to be intelligent political actors on their own.” Lately, as publications across Condé Nast have unionized, and there has been a rise in class consciousness across the journalism industry, the staff of Teen Vogue have been making increasingly bold efforts to carry the values they’ve instilled in the magazine off the page; organizing now continues apace. But in taking the political power of girls seriously, Teen Vogue presents a paradox, as its employees find themselves at odds with Condé Nast, a bastion of corporate media that sells ads to young women.

“Women’s media is often looked down upon in terms of politics, and that only gets further magnified when you add the teen girl to it.”

It was March 2016, just a few weeks after Beyoncé performed “Formation” at the Super Bowl, when Nancy Reagan died. Vogue paid tribute with a piece by Hamish Bowles, American Vogue’s international editor at large, who wrote of Reagan’s “brisk, polished, and generally faultless American high style.” Glamour, another Condé Nast magazine, published a similar homage, compiling a “most notable looks” slideshow of Nancy Reagan slow-dancing in a Galanos gown and walking alongside Princess Diana in a red Adolfo suit. Everything went the expected way of glossy coverage. That is, until a few days later, when Teen Vogue took a different tack, publishing a piece with the headline: “Former First Lady Nancy Reagan Watched Thousands of LGBTQ People Die of aids.”

“That was when a sort of bomb went off internally,” Phillip Picardi, who had been hired the year before as Teen Vogue’s digital editorial director, told me. He had been brought in at the age of twenty-three to grow the online presence of the magazine—which still ran on a decade-old content management system—and to connect with actual teenagers. Picardi, who is gay, said that there was no way Teen Vogue was going to run a puff piece on Reagan. The price of the criticism was a torrent of hate mail that flooded the inboxes of Condé’s top executives. Picardi got a message that Wintour wanted to see him. He braced for a scolding—not only had Teen Vogue pissed off conservatives, it had also gone against its parent publication. But the meeting was suddenly called off. Later, he learned that he had been saved by an unlikely source: “Someone from Elton John’s aids Foundation emailed Anna, saying, ‘Thank you so much for Teen Vogue’s bravery in covering the truth of the story,’ ” Picardi recalled. “Long story short, I was not reprimanded for the piece.”

Picardi had been pushing for bold political coverage since before he started; when he interviewed with Astley, he presented a forty-five-page deck on how Teen Vogue was underestimating its audience. He highlighted news stories he thought teenagers cared about that Teen Vogue had neglected to cover: Black Lives Matter protests, Indigenous rights, representational wins in Congress. “Amy was like, ‘You think teenagers would click on this?’ I said, ‘Yes, there’s a chance we can make real waves here.’ ” Astley brought him on and gave him her blessing. Elaine Welteroth was the beauty editor at the time; soon, at the age of twenty-nine, she was promoted to run the print magazine, becoming the youngest and second Black editor in chief in Condé Nast history. Along with Marie Suter, the creative director, the new guard at Teen Vogue prepared to take on the emergent Donald Trump era.

One of Picardi’s early hires was Sade Strehlke, who came from the Wall Street Journal and was put in charge of Teen Vogue’s budding political coverage, along with that on wellness, home decor, and campus life—essentially everything aside from the core fashion, beauty, and entertainment fodder. Early posts on the Republican debates were largely ignored or slammed by commenters on social media, who told Teen Vogue to stay in its lane. But the magazine kept trying. Strehlke described the sense of reinvention in the office as akin to working in a startup within a legacy institution. The team became one of the most diverse at Condé Nast; its political coverage grew more ambitious. Teen Vogue produced videos interviewing Native American girls about Standing Rock and published an advice essay by Hillary Clinton (“Vote, and inspire others to vote too”).

At the same time, Teen Vogue, like most publications chasing BuzzFeed-style virality, fell prey to some of the worst compulsions of the clickbait era; the magazine was publishing as many as seventy posts per day, with a staff of around fifteen people. Most of those pieces focused on classic girl-glossy topics (a makeup hack listicle, “runway inspired” prom looks); many of the political takes were basic-liberal (“You’ll Get Chills When You Listen to Hillary Clinton’s 1969 Wellesley Commencement Speech”). But by one metric, the content strategy proved successful: in its first year, the My Life vertical, which included politics, rose in traffic by 400 percent. “The evolution of wokeness from 2015 to 2016 across American culture was huge,” Strehlke said. “We just jumped on that bandwagon, and the audience came. They were always there—they just didn’t know we were there for them.”

The higher-ups at Condé Nast paid attention mainly when something broke through the news—like the Nancy Reagan obituary or, that December, a column called “Donald Trump Is Gaslighting America.” Written by Lauren Duca, who was working on contract as a Teen Vogue weekend editor, the piece was seen more than a million times and boosted by celebrities. (“Donald Trump is our president now,” Duca declared. “It’s time to wake up.”) Many readers expressed their surprise that a magazine for teenagers could be so incisive; others pointed out the condescension of that view and noted that Teen Vogue had been covering politics for more than a year. Duca became a star—even more so after a combative appearance on Tucker Carlson’s show, on Fox, in which he told her to “stick to the thigh-high boots.”

“All of a sudden,” Picardi told me, “Vogue’s PR was all up in our business.” Condé’s communications machine, notoriously heavy-handed, loomed large. When the New York Times magazine profiled Welteroth, the author noted that a Condé publicist was constantly present. Here was a campaign to be carefully managed: the publication that had once featured Ivanka Trump was suddenly on the map as the center of the #Resistance against her father. As Welteroth told the Times: “We’ve come to stand for something, and it has resonated.”

The buzz proved to executives that Teen Vogue’s political branding was popular, and thus monetizable. In 2017, Picardi was given a budget to hire a dedicated politics editor; he brought in Alli Maloney, who had just spent over a year reporting on institutionalized racism in the Columbus Police Department. Maloney, to whom many staffers attribute the magazine’s sharp left turn, worked with columnists like Kim Kelly, a labor reporter who wrote a widely read explainer on unions, and brought on Lucy Diavolo, who published hard-charging political columns. The site continued to elevate teen voices through interviews and commissions, including an op-ed by Emma González in the wake of the Parkland shooting. “I wanted the mission to be reflecting the intelligence of young and marginalized people whose perspectives were being dismissed,” Maloney said. Teen Vogue’s traffic shot up exponentially, from two million monthly unique views in mid-2015 to twelve million less than two years later.

For the most part, staffers who worked on Teen Vogue’s political coverage felt free to set the site’s direction without interference from above; most were doubtful that Wintour or other executives read much of the site or fully understood the political changes as they were happening. Wintour seemed more hands-on when it came to Teen Vogue’s fashion and beauty coverage, which mattered most to the advertisers on whom Condé Nast relies. (Peoples Wagner told me that, at least during her tenure, Wintour was “incredibly involved” with all aspects of the publication, including politics; they met weekly. “She had a lot of opinions on where our coverage was going and read the site.”) But what was overlooked, amid the magazine’s ideological transition, were the many ways in which the politics of its fashion coverage could be just as controversial as the politics section itself—Teen Vogue would call in broad terms for capitalism to be dismantled without anyone batting an eye, yet the magazine placed less emphasis on reporting that scrutinized the labor conditions of garment workers. The same tension could frequently be found in Duca’s writing; the spectacle around her “gaslighting” piece belied the fact that her takes (obvious at best, reductive at worst) were actually behind the times. (“Duca exemplifies a trend typical in contemporary feminist thinking: the belief that any woman in power must be a good woman,” as Haley Mlotek wrote in a review of Duca’s book.) The superficiality of the pussy-hat moment was already being drowned out by Teen Vogue’s sharpening political voice.

After Biden’s inauguration, Wintour sat down Teen Vogue staffers and asked them whether the magazine should continue covering politics.

Teen Vogue received national acclaim for its political journalism, yet profit did not immediately follow. Picardi recalled the frustrations of working with a revenue team inside a behemoth media company that he felt was “stuck in its ways” and unable to capture Teen Vogue’s sensibility. “They were scared because the tone of the publication was just a lot more aggressively progressive than they were used to,” he said. “It was hard to convey that to the right advertisers and right marketers.” By November 2017, when Condé Nast laid off eighty people across the company, it announced that the print edition of Teen Vogue would be eliminated. Staff found out about the cuts through a Women’s Wear Daily article. In her book More than Enough: Claiming Space for Who You Are (No Matter What They Say), Welteroth writes that she was given only last-minute notice of the closure: “I knew on a gut level that pulling the plug on the magazine this abruptly after a year of record growth and with promising new ventures on the horizon was ill advised.” She met with the CEO of Condé Nast to make a case for keeping print, and asked: “If the company is not prepared to invest in the future of Teen Vogue, would you consider allowing me to help find an investor who is?” The answer was no.

In January 2018, Welteroth resigned from the company. (She wrote of the decision: “My mission at Teen Vogue was to make young people whose voices had been marginalized feel seen, centered, and celebrated. Anna had given me the space and permission to fulfill that mission. I did what I came to do.”) Picardi turned his attention to launching them, a Condé-branded LGBTQ title, but left later that year to run Out magazine. Wintour signaled a return to Teen Vogue’s fashion roots by hiring Peoples Wagner, then the fashion editor at The Cut, as the magazine’s next editor in chief. As the months went by, in a churn of layoffs and reshuffling, employees began to lose patience. “The management changes constantly meant there were new labor experiences that differed from the last, so the ways that we had to work shifted, and that created total confusion and chaos,” Maloney said. In two years at Teen Vogue, she had five bosses.

Under Peoples Wagner, the pace started to become more humane, slowing down from the clickbait days. “Being a newsroom where every single thing that Trump says has to be something we report on is exhausting,” Peoples Wagner said. “It felt like we needed to get to a place where we obviously would pay attention to the news but have a bit more of a curated perspective.” To pull in new sources of revenue, she placed an emphasis on events, like the Teen Vogue annual summit, backed by companies such as Victoria’s Secret and Google; during the pandemic, the magazine hosted a “virtual prom” sponsored by Axe and Chipotle. The publication became sustainable and profitable. (As Peoples Wagner told me, she was “intentional in choosing stories, themes, and people that still aligned with what we wanted to do, but were also exciting to certain advertisers and helped sustain the health of the brand. Because ultimately, if we don’t have a place to do this work, then what was the point of this all?”) All the while, Mukhopadhyay, who had recently started her tenure, steered the politics section along with an editor named Allegra Kirkland; the team covered climate strikes and advocated abolishing landlords. “Teen Vogue had pivoted to covering more politics, but they had yet to fully integrate it into the brand,” Mukhopadhyay said. “I was hired to help do that, and my interest was in deepening the reporting and analysis and showcasing the real force young people were emerging as in the political landscape.”

Peoples Wagner was also political in her way, pushing Teen Vogue to feature those who were not traditionally found in the pages of Condé Nast glossies. “When you talk about the traditional fashion industry, it’s often based in European beauty standards,” she said. “For me, it was really important to make sure that if I’m a young person reading Teen Vogue that I feel seen and heard on this site every single day.” Sammie Scott, a former social media manager at Teen Vogue, said that when she started, in 2017, around a third of the staff were Black, which was unusual—and exciting—for a major publication. “We were politically forward,” Scott said. “Mainstream Black publications wouldn’t have been able to do the same things that I was able to do at Teen Vogue.”

During the same period, a boom in labor organizing reverberated across the media world; staffers grew more vocal about diversity, fair pay, and editorial standards. Within Condé Nast, The New Yorker, Pitchfork, Wired, and Ars Technica unionized. At Teen Vogue, a sense of collective energy percolated through the staff, who at times made their frustrations with management public. Last year, when the site published a glowing article about how Facebook was “helping ensure the integrity of the 2020 election,” without a byline, and Sheryl Sandberg, Facebook’s COO, shared the piece on social media, the story began trending; as it turned out, the article was a paid advertisement—and most of the staff had no clue. A reader tweeted, “What is this Teen Vogue?” Scott composed a reply from the magazine’s official account: “literally idk.” Wintour sent down a directive to delete the tweet, which Scott did, while executives scrambled to respond to criticism; in the end, the article, which Facebook claimed was a “misunderstanding,” came down. When I asked Scott about the tweet, she said, “Here’s the thing—it was a good idea. I stand by it.” The episode may have been an embarrassing misfire for the company’s corporate-sponsorship strategy, but for the staff it was an opportunity to punch up, in keeping with their vision for the Teen Vogue brand.

In discussions about Teen Vogue and its discontents, it’s often forgotten that teen magazines have always been political—that was true as far back as the Victorian era. “The magazine has always been a space way more for girls than for boys,” Natalie Coulter, an associate professor of communications at York University, told me. “It’s something that can be done in private spaces, because girls can’t take to the streets the same ways that boys can—there’s safety issues boys don’t have to face.” Publications for teen girls can provide a forum for self-actualization; they have also, historically, been colonialist—the conservative contradictions of teen mags started early on.

So it makes a certain sense that Seventeen, the prevailing teen publication of the modern age, was founded in 1944 by Walter Hubert Annenberg, a Republican media tycoon and close friend of Ronald Reagan’s. Under Helen Valentine, the magazine’s first editor, Seventeen forged a lucrative business in an untapped market, filling its pages with more advertising than any other women’s outlet before. To help advertisers visualize the demographic, the magazine invented “Teena, the Prototypical Teenage Girl,” a white sixteen-year-old from a middle-class family with a penchant for spending, whose favorite thing to read was, of course, Seventeen. The original influencer, she was “within a few years of a job . . . a husband . . . a home of her own,” per the pitch. “Open-minded, impressionable, at an age when she’s interested in anything new, Teena is a girl well worth knowing—surely worth cultivating.” Articles advised on how to diet and keep a boyfriend; Seventeen prescribed a traditional view of young womanhood. Other publishers spawned their versions—YM, CosmoGirl, Elle Girl—but it was Seventeen that lasted through the years, albeit now in pared-back form.

While Seventeen remained dominant, Sassy, which debuted in 1988 under the editorship of Jane Pratt, became beloved for being political in a different way: a feminist alternative to the usual glossy teen fare. With a staff that averaged twenty-four years of age, Sassy ran pieces on losing your virginity alongside roundups of the best cheap makeup—because, as the editors wrote, “even though a certain president with the initials G.B. says the recession is over, we know better.” The magazine cultivated community; as Jesella and Marisa Meltzer write in their book How Sassy Changed My Life (2007), Sassy’s draw was how it “questioned all the tenets that other teen magazines held dear.” It understood that fashion, beauty, and politics were not separate categories.

Sassy shuttered in 1994, but its ethos went on to influence online publications—among them Tavi Gevinson’s now-defunct Rookie, notable for being staffed and led by teenagers. Sassy’s progeny also included Jezebel, The Hairpin, Worn, Feministing, Bitch, and Bust. Kate Dries, a former Jezebel editor, has compared these sites to “consciousness-raising circles,” crediting them with expanding the scope of women’s magazines. “One hopes we reach a point where they’re no longer a necessary antidote to a flawed system, but simply a cohesive part of an improved landscape,” she wrote in 2014. Teens blogging on Tumblr, and now posting on Instagram and TikTok, carry the torch, demonstrating an audience for inclusive, queer, and Marxist storytelling.

Now, as one of the last teen publications standing, Teen Vogue has surpassed even Sassy’s political chutzpah. When I spoke with Coulter, she acknowledged a tension between the way Teen Vogue at once politicizes teen girls and markets to them. But, she said, “one of the only places they have a voice is in consumer commodity capitalism, particularly because they’re kids—they’re not working, they’re not in halls of power, and there’s not a lot of spaces for them. These kinds of media spaces are often where girls can be political.”

Being editorially assertive can, however, pose challenges to a publication’s bottom line. “Teen magazines have always been known to be extremely beholden to advertisers, particularly because advertisers have particular feelings about teenage girls,” as Jesella told me. In the first year of Sassy, right-wing religious groups called for a boycott over the magazine’s sex positivity; advertisers began to withdraw. Teen Vogue ignited a similar conservative firestorm in 2017, when it published a guide to anal sex. Right-wing mommy bloggers and members of pro-life organizations began tweeting a campaign to #PullTeenVogue. Skittish companies canceled their ads; staff members received violent threats. Scott said that some angry readers even called the FBI. “What’s the FBI going to do?” Scott said. “They’re like, ‘Let me know if any of them are communists for real.’ ”

Sarah Emily Baum, who was a Teen Vogue reader before she became a contributor, at the age of seventeen, told me that the magazine made her feel valued as a participant in the political discourse. “A huge amount of the op-eds are written by students, compared to other national news outlets,” she said. Commentary that trivializes Teen Vogue’s political coverage tends to downplay the importance of personal knowledge, she added. “It begs the question: Who would more authentically or accurately report on, say, queer experiences? A seventeen-year-old queer reporter, or a fully grown adult reporter who is straight and cisgender and doesn’t have any queer friends but has a master’s in journalism?”

If leftist ideals have become a defining feature of Teen Vogue’s coverage, they have not always been reflected in the workplace. During Welteroth and Picardi’s era, the publication’s staff became one of the youngest and most diverse teams at Condé Nast; those employees—now eleven people in editorial, and around twenty in total—have been responsible for elevating the magazine’s inclusion and class consciousness. But company-wide, Condé Nast has remained a largely white place (according to an internal report, 77 percent of the senior leadership and 69 percent of the editorial staff are white), with vast gulfs in compensation between high- and low-level employees. Maloney recalled that, when she asked a manager to address pay disparities at Teen Vogue, she was told, “You all shouldn’t be talking among yourselves about how much you make.” There is a pervasive sense, staff members told me, that one should feel lucky just to be there.

That dynamic has, at times, presented a conflict of principles: while the magazine’s articles have promoted mental health at work, employees have been pushed to the limit. A former Teen Vogue employee, who spoke on the condition of anonymity, told me that she worked from her grandmother’s wake—the one day she’d taken off all year. In the office with Welteroth and Picardi, people said, it was common to see colleagues cry at their desks. Twice, medics were called to assist people who had fainted in the bathroom, which their colleagues said was caused by stress. “All of the voices we were saying we stood for were run bone dry in that office,” Maloney told me. “I got so used to being at my desk at night. The motion sensor lights would turn off, and I’d wave my arms so they’d turn back on—and I wouldn’t be alone in the office. When I got home, I would continue working. It became so intense that I would preschedule my emails so they went out at 8am—at a normal time—but I was writing them at three or four in the morning.”

Most of the employees I spoke with, past and present, blamed the dysfunction primarily on Condé Nast’s corporate bosses; some believed that Teen Vogue’s managers—often young, of color, and under-resourced—were at fault, too, but had been set up to fail. Welteroth writes in her book about being underpaid and overworked; she found herself up against “ever-tightening budget constraints, a shrinking staff, and some of the same systemic issues that made work feel like an uphill battle.” Picardi wrote last year about his “ferocious ambition” at Condé Nast, which mingled with a fear that he “would be revealed as an impostor.” To prove himself, he worked from seven in the morning to ten or eleven at night; weekends, too. When I asked how he may have contributed to a toxic office culture, he told me that he had a “multiplicity of regrets.” Feeding the clickbait economy had grown Teen Vogue’s brand, but it was complicated. “I wish I didn’t look at corporate KPIs as a metric of success and had looked at how my employees were feeling coming to work every day,” he said. It was a tough balance. “I never would have kept my job if those were the metrics of success.” Peoples Wagner told me, “We didn’t have the same resources as a lot of the other publications, and that can be frustrating as an editor when you have really big ideas and want to create an amazing body of work.” She was proud of what the magazine accomplished, she said; still, “it is no secret I wanted Teen Vogue to be able to do more.”

In the past year, Condé Nast has been forced to acknowledge racism in its workplace and in its coverage. The most obvious example: Adam Rapoport, the editor in chief of Bon Appétit, resigned after a photo circulated of him dressed in brownface; employees of color at the magazine then revealed how much less they’d made compared with their white counterparts. During last summer’s protests against racist policing, Wintour apologized to Black members of her staff, writing: “I want to say plainly that I know Vogue has not found enough ways to elevate and give space to Black editors, writers, photographers, designers and other creators. We have made mistakes, too, publishing images or stories that have been hurtful or intolerant. I take full responsibility for those mistakes.” When I reached out for an update, Condé Nast provided a statement: “It’s been a top priority for our People team to evolve our compensation processes and systems over the past year, including a new and uniform job architecture with standard levels and ways of ensuring consistency and equity across our organization.”

Many at Teen Vogue said that the situation there has been especially complicated. Since the start of this year, both Peoples Wagner and Mukhopadhyay have left their jobs. Around Inauguration Day, with Trump gone, Wintour sat down with members of the Teen Vogue staff and questioned whether the magazine should continue covering politics. There was the McCammond controversy. Right-wing media dug up tweets from a Teen Vogue social media editor who had used the N-word. In April, Condé Nast promoted Danielle Kwateng, Teen Vogue’s entertainment and culture director, to become the new executive editor. “We at Teen Vogue have read your comments and emails and we have seen the pain and frustration caused by resurfaced social media posts,” Kwateng wrote in a statement published on the magazine’s site. “While our staff continued doing the groundbreaking and progressive work we’re known for, we stopped posting it on social media as we turned inward and had a lot of tough discussions about who we are and what comes next.”

Rather than stick around, some Teen Vogue employees have opted to give up on their media careers. Scott, who quit at the end of 2020 to work for a beauty company, told me that her mother once asked if she would ever return to Condé Nast—if, say, she were offered a top role. “A lot of things would have to be different,” Scott said. “Anna would have to be dead or something.” (That was mostly a joke, though Wintour’s power can feel so immense to employees that it seems to have grown beyond her.) Scott continued: “I can’t imagine being a Black person in a leadership role at Condé—if you aren’t already a terrible person, it’s going to make you a terrible person.”

In May, after the dust from McCammond’s ill-fated appointment had mostly cleared, Condé Nast announced that Versha Sharma, the managing editor of NowThis, a video-news platform, would be the new editor in chief of Teen Vogue. Sharma—who is thirty-five, with long, swooping black hair and a sense of style that is more approachable-journalist than high-fashion maven—was eager for everyone to move on from what had just transpired. “It’s not my place to comment on that,” she told me. “The team is in a good place right now, where everybody’s excited to focus on our work.”

That work appeared to be continuing on with the magazine as she found it. The June digital cover story profiled Marie Newman, a Democratic member of Congress, and Evie, her transgender twenty-year-old daughter, in their fight against anti-trans legislation. In August, Sharma unveiled the first cover she’d commissioned, on Maitreyi Ramakrishnan, which she described as “brown girl vibes + back to school all in one.” She also pointed me to an interview Teen Vogue ran with a Texas valedictorian who went viral when she switched out her graduation speech to talk about abortion rights. “Nobody else in the industry who interviewed her can do it the way that Teen Vogue can,” Sharma said, “because it was a young person talking to another young person who really understands what we’re up against.”

Sharma didn’t want to mess with what made Teen Vogue appealing. Even with Trump out of office, she told me, she saw no reason to change the political sensibility—and besides, the fact that socialist politics have become both a practice and a trend has implications for the currency of the magazine. “I’m excited to show that, regardless of who the president is, young people want to hold them accountable,” she said. She was pleased with an op-ed calling on Biden to sign an executive order canceling student debt. (“So far Biden has offered nothing but stall tactics,” it read.) Over the summer, the magazine published an obituary that harked back to Nancy Reagan’s: “Donald Rumsfeld, Former Defense Secretary and Accused War Criminal, Dead at 88.” (Picardi tweeted the piece approvingly, with a note: “Aaaand they’re back!”) Sharma’s ambitions for growth focus on video, drawing on her background at NowThis. “That was one area of improvement that I saw, coming into this role,” she told me, “because young audiences are the biggest audience for video, social video, YouTube, TikTok, whatever it may be. So I think there’s a lot more we can do there that will hopefully lend itself well to revenue as well.”

When it comes to the office environment at Teen Vogue, Sharma said that “work-life balance is incredibly important.” She had heard the complaints of the past. “I’m very sensitive to the fact that people are burned out,” she said. “I’ve gone through burnout myself, and I completely understand that—just like I want to emphasize young people’s mental health, I want to make sure we’re doing that internally, too.” The mood today, it seems, teeters between positivity and nihilism; Teen Vogue staffers are fully aware of the strange tension in producing justice-oriented and socialist coverage in the service of a historically racist and classist company, even as they are proud of the work they’ve been able to accomplish within those constraints. I asked Sharma how she felt coming into that dynamic. “I have a very outspoken background on all of those issues, including in the journalism industry,” she said. “I’m brand new, but so far executive leadership has been really receptive to these conversations. I think my hiring is kind of like the proof in the pudding that they’re listening—they’re listening to staff, they’re listening to the audience.” Thus far, Sharma added, Wintour has been “really supportive.” (A Condé Nast publicist was present for our call.)

Around the time I spoke with Sharma, union organizing at Condé Nast was heating up. In June, during protracted contract negotiations with staffers of The New Yorker, Pitchfork, and Ars Technica, the company narrowly avoided a strike: they ratified their first union contract, which included a base salary of fifty-five thousand dollars that would rise to sixty thousand by 2023, a cap on healthcare cost increases, and defined working hours. The deal applied only to those three publications but set a precedent for employees across the company. “This agreement sets a great example for the rest of the industry, and I’m excited to see that put in practice,” Sharma told me. She’s likely to hear more about union organizing plans soon.

In a sense, the fact that Teen Vogue still exists is a feat; for years now, there has been a looming sense that Condé Nast might decide it’s more of a hassle to keep the magazine running than to deal with the public relations nightmare of shutting it down. A union battle could complicate matters. But if the company wants to stay relevant and retain talent, it will need to find a way to support the people and politics able to carry it into the future.

Recently, Maloney told me that she remembered a speech Wintour gave during an office party—a gathering to celebrate Peoples Wagner’s hiring along with the promotion of top editors at them and GQ. “Anna’s introducing these new editors and explaining what a group of visionaries they are and what a moment it is in time,” Maloney recalled. Then, she said, Wintour ended her speech with a request to the staff: “So please don’t leave.”

Maloney went wide-eyed. “I was shocked that she said that, because she must know,” she said. “She knows why the talent leaves.” Within a month, Maloney resigned from Teen Vogue with no job lined up.

Clio Chang is a freelance reporter based in New York. She writes about politics, culture, media, and more.