In November, just before I went to see Jerry Brown at the annual meeting of the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, some eleven thousand climate experts signed a statement declaring “clearly and unequivocally that planet Earth is facing a climate emergency.” At eighty-one, Brown, the former governor of California, was retired, but not really, having committed himself to fending off environmental disaster. Recently, he had testified before a House subcommittee, calling an attack by President Trump on California’s auto emissions rules “just plain dumb, if not commercially suicidal.” A month before that, he’d announced the creation of the California-China Climate Institute, a bilateral research and training initiative “to spur further climate action.” And just before finishing his last term as governor, he’d signed on as the executive chair of the Bulletin, which was eager to stake out territory in the climate fight.

I’d arranged to interview Brown about his choice to join the Bulletin, a nonprofit magazine founded in Chicago in 1945 by conscience-stricken alumni of the Manhattan Project. The Bulletin covers all things nuclear and is best known for its annual Doomsday Clock announcement, which draws on expert opinion to report just how close we are to the “midnight” of man-made apocalypse. But the publication’s original remit—to help “formulate the opinion and responsibilities of scientists” and “educate the public” about the many “problems arising from the release of nuclear energy”—has broadened considerably. It now devotes equal attention to the threat of the climate crisis, including in the setting of the clock.

In this regard, the Bulletin and a post-gubernatorial Brown were an ideal match. The meeting I attended, at the regal University Club in downtown Chicago, was Brown’s second with the science and security board, a group of subject-matter experts who set the clock and advise the editorial staff. (The Bulletin also has two other boards: the governing board, a corporate and philanthropic fundraising body, and the board of sponsors, which boasts thirteen Nobel laureates.) A few hundred people arrived, palling around and getting ready to talk all things apocalypse. The dress code for the event had called for business attire, but Brown turned up in crumpled slacks and a navy-blue sweater—a suitcase screwup, he explained.

Why the Bulletin? I asked. “Number one is, of course, the reduction of the nuclear threat, but climate is another huge threat to humanity,” he said. “And the Bulletin, by linking the two threats, can increase public awareness, get people thinking about the big threats that humanity faces.” Brown complained, in his jocular, pugnacious way, that the American news media’s “servitude to the concept of the news of the day” is partly to blame for public ignorance about climate change. He asked me repeatedly, “How can journalism cover something as diffuse and general and gradual as climate change?” As we chatted, searching for answers, I thought of the untold amount of carbon we’d all combusted to get to Chicago.

I next saw Brown at the opening luncheon, in the buffet line among Bulletin funders and fans. The crowd resembled that of a classical-music concert: old, white, intellectual. The day included three sets of workshops, led by eminent scientists and policy wonks, then a closing plenary session and dinner banquet at Chicago’s Palmer House, a grand hotel dating to the late nineteenth century. At the dinner, Brown delivered an energetic, free-flowing speech. “The worse it is, the more excited I am,” he said, the it being our current geopolitical, nuclear, and climate morass. “Let’s get it done!”

That second it—the avoidance of total destruction—aptly distilled the Bulletin’s mission. Since the atrocities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the magazine has tried to convey the grave danger we’ve imposed on ourselves. Today, though the possibility of nuclear war remains real, the climate crisis feels just as daunting and consequential. Environmental scientists know this, as do journalists who report on global warming. Yet the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists may be the only publication to cover climate change with an approach that is explicitly existential.

What time is it? At the 2020 announcement of the Doomsday Clock, the Bulletin’s leaders declared us closer than ever to midnight. Lexey Swall Photography / Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists

In 2017, during a seemingly endless, ever-escalating row between President Trump and North Korean leader Kim Jong-un, the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists was permanently tabbed in my browser window. What some were calling a new “North Korean nuclear crisis” wasn’t really new or even a crisis so much as the crackling of a rather constant fire. Still, as a Korea watcher with family on the peninsula, and given the “statesmen” involved, I felt frightened and looked to the Bulletin as a vital source of news and commentary. The magazine had, after all, invented the nuclear beat.

From the very first issue, a slight, mimeographed newsletter published on the fourth anniversary of the attack on Pearl Harbor, the Bulletin appealed to America and the rest of the world to eliminate nuclear weapons and establish “efficient international control” of atomic energy. Progress “will be useless if our nation is to live in continuous dread of sudden annihilation,” the editors said at a conference in Moscow. “We can afford compromises, disagreements, or delays in other fields—but not in this one, where our very survival is at stake.” A few years on, the Bulletin published the text of a speech by Albert Einstein, delivered to journalists at the United Nations, in which he asked why global cooperation hadn’t yet staved off the threat of apocalypse. Perhaps it would be different, he suggested, if the atom bomb were not “one of the things made by Man himself.” Einstein later founded the Bulletin’s board of sponsors.

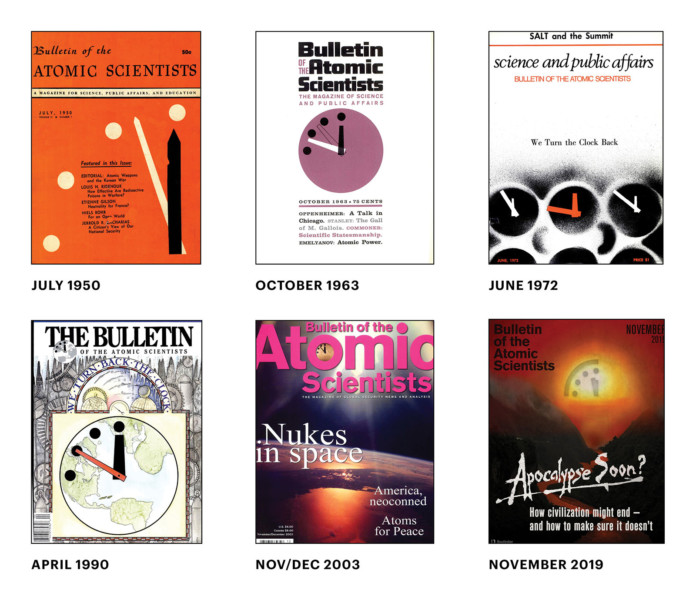

The Bulletin evolved from a newsletter into a magazine, headquartered at the University of Chicago, and Martyl Langsdorf, a landscape painter and the wife of a Manhattan Project alumnus, designed a symbolic cover: an analog clock, set at 11:53pm, to represent the imminence of our self-destruction. In 1949, when the Soviet Union tested its first nuclear device, Eugene Rabinowitch, the Bulletin’s coeditor, decided to animate Langsdorf’s clock, winding it four minutes closer to midnight. It has ticked forward and backward ever since—through the proliferation of ballistic missiles; the catastrophes at Three Mile Island, Chernobyl, and Fukushima; and the adoption of and American withdrawal from the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty. The Nuclear Notebook, a research column of hair-raising erudition, has appeared in every issue since May 1987 and is second only to the Doomsday Clock in Bulletin influence. Each Notebook installment analyzes a category of stockpile—tactical nuclear weapons, for instance, or the Chinese nuclear arsenal—down to the quantity and types and locations of various arms and fissile materials.

The interests of the magazine have always overlapped with those of environmentalists. Early Bulletin scientists expressed a desire to make atomic energy a clean, limitless alternative to fossil fuels. That did not, of course, come to pass; more apparent were various kinds of long-term damage, from nuclear tests to plant meltdowns to radioactive waste buried on- and offshore, all of it documented in the Bulletin. There’s still no consensus on nuclear power. At the annual meeting, Robert Socolow, a member of the science and security board and a Princeton professor emeritus, said in a presentation, “I’m still going back and forth on nuclear energy, because of the coupling of nuclear power and nuclear weapons.” There is always “some probability” of disaster, he added.

Atomic energy, in any case, never came close to rivaling fossil fuels, and the subject of climate change appeared in the Bulletin as early as November 1961. “Climate to Order,” an article-cum–thought experiment by H.E. Landsberg, a German climatologist, described geoengineering—that is, hacking the atmosphere (reflecting sunlight, injecting chemicals into the stratosphere, etc.)—avant la lettre. In theory, Landsberg wrote, it would be great to customize our environment, but “When we are changing the climate of the whole world, a mistake could be disastrous.” In 1970, the Bulletin ran another piece on geoengineering, this time in relation to “polar ice” and “man’s inadvertent influences on global climate.” By 1972, a long, poetic account of the loss of forests and arable land would warn, “There is plenty of evidence that man is the principal cause of this change.”

When I visited Rachel Bronson, the CEO and president of the Bulletin, in the magazine’s Chicago offices, she plucked a bound library volume from her shelf and opened it to February 1978. “Is mankind warming the Earth?” William W. Kellogg, a meteorologist, queried in the magazine’s first climate-change cover story. “The answer is, I believe, an unqualified ‘yes.’ ” Kellogg’s article might have been written today, so salient are its arguments against delayed action and the conflating of extreme weather and atmospheric transformation. He included a message to colleagues who “maintain that we should not publish any conclusions about the response of the climate to anthropogenic influences until we have done more homework,” expressing his disagreement “with such a conservative and noncommunicative attitude because the stakes are so great, the issues so fundamental to the future of society and most of all because some decisions are upon us that depend on every scrap of insight we can muster.”

By the end of the Cold War, most scientists were aware of the dangers of climate change and its relation to atomic and geopolitical concerns. Around the time Bill McKibben published The End of Nature, the first mass-market account of global warming, in 1989, the Bulletin was running pieces on the science of climate change “side by side with heated denials that global warming posed any threat at all,” historians David Kaiser and Benjamin Wilson observe in a special seventieth-anniversary issue of the Bulletin. The magazine also recast the debate over nuclear energy “amid new apprehension about greenhouse gas emissions and implications for global warming.” Len Ackland, the editor from 1984 to 1991, told me that it became clear “we needed to address longer-term environmental dangers.” To that end, he commissioned new artwork from Langsdorf: in her cover illustration for the October 1989 issue, the circle of the clock encloses a blue-and-white map of the world, the minute and hour hands radiating out from the North Pole. In 1992, the Bulletin published a major speech by Mikhail Gorbachev that set out environmental priorities for a post-Soviet world: “The prospect of catastrophic climatic changes—more frequent droughts, floods, hunger, epidemics, national-ethnic conflicts, and other similar catastrophes—compels governments to adopt a world perspective and seek generally applicable solutions.”

The Bulletin has vacillated in style over time, toggling between academic journal and science magazine, but has always maintained a certain seriousness. When I spoke to Bronson, she told me that tradition and expertise are no longer enough. “In the moment of populism in which we’re now operating, we’d better inform the populace,” she said. “Our power will come from having an educated and devoted following that’s larger than it is right now.” Recently, the Bulletin has adjusted its idioms; leaned more on interviews, explainers, personal essays, and multimedia; and stretched beyond an author base of older white male technocrats from Europe and the United States. There’s the Voices of Tomorrow column, which ran a moving essay by four teenage activists, including Isra Hirsi, Congresswoman Ilhan Omar’s daughter: “Adults won’t take climate change seriously. So we, the youth, are forced to strike.” There’s elegant multimedia reportage, such as deputy editor Dan Drollette’s “Tilting toward windmills,” about a test wind farm on Block Island, Rhode Island. And there’s refined polemic: for example, “Let science be science again,” by Yangyang Cheng, a Chinese physicist based in Chicago, on science advocacy in the age of Donald Trump. A popular video series, “Say What? A clear-eyed look at fuzzy policy,” produced by multimedia editor Thomas Gaulkin, demonstrates that, even though the Bulletin is nonpartisan, it’s religiously pro-science.

“Some decisions are upon us that depend on every scrap of insight we can muster.”

Ticktock: Martyl Langsdorf, a landscape painter and the wife of a Manhattan Project alumnus, designed a symbolic Bulletin cover: an analog clock that would represent the imminence of our self-destruction. That clock would become the magazine’s visual touchstone. Courtesy Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists

In recent years, the Bulletin website has more than quintupled its traffic, from about 42,000 visits per month in 2013 to 236,000 per month today. The audience remains small but is also—judging from the comments section and social media—well connected and atypically informed: scientists, graduate students, journalists, the kinds of people who subscribe to Scientific American and Foreign Affairs. In response to a recent article on the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change that debunked the supposed coming of a “little ice age,” commenter Cjones1 wrote: “You forgot to mention that less solar radiation allows more cosmic radiation which effects [sic] cloud cover. The IPCC predictions have been less accurate than a bone throwing shaman.” Fifty-five people responded to this with a thumbs-up.

The Bulletin discontinued its print edition in 2008 but maintains a distinction between its paywalled bimonthly magazine and other articles. A yearly subscription costs eighty-six dollars and comes via Taylor & Francis, a profitable British publisher of scholarly books and journals. Since 2011, John Mecklin has served as the Bulletin’s editor in chief. He supervises six editors, spread out across the United States, who commission and write; seven other staff members handle administration, public relations, and fundraising. Collectively, they aim to grow the magazine’s readership, assign more illustrations, and invest in narrative and investigative journalism. “I’m in the process of commissioning a story right now, paying somebody two to three dollars a word,” Mecklin told me. “The Bulletin is doing well financially, but I can’t pay what The New Yorker pays somebody, or I can’t do it for very many stories a year.” Most pieces are written for nothing—“donated,” as Mecklin put it—by experts with day jobs. One of Mecklin’s predecessors, Mark Strauss, recalled compensating at least one contributor with a Bulletin T-shirt.

When Mecklin took the job, climate represented just “a quarter or 30 percent” of the magazine, he told me; it’s now “more like 40 percent nuclear, 40 percent climate.” As he explained, “What has evolved and changed since I’ve been editor is that there are now three areas of focus: it’s nuclear, climate change, and this area we call disruptive technologies”—such as artificial intelligence and disinformation—a sort of “threat multiplier of the first two.” Both Mecklin and Bronson described this expanded mission as logical and necessary, and in line with the Bulletin’s history of tackling the impacts of cutting-edge science.

When I listened in on a recent editorial meeting, via Skype, I was struck by the magazine’s simultaneously banal and illustrious character. The editors did what all editors do: they evaluated pitches and commissions, reviewed social media statistics (e.g., an “SUV shaming” story, by contributing editor Dawn Stover, that was “doing well on the interwebs”), brainstormed story ideas, and planned coverage. But every so often, someone would refer to a famous politician or scientist (e.g., Siegfried Hecker, a Stanford physicist who has personally inspected North Korea’s nuclear arsenal) not as a dream subject or occasional source, but as a friend and adviser to the magazine. On questions of climate, for instance, they might consult Elizabeth Kolbert, a Pulitzer Prize–winning New Yorker writer who sits on the science and security board. This is a publication with extraordinary history and reach. I thought of something Mecklin told me when we first spoke: “We want to be read in the White House, at the Kremlin, and at the kitchen table.”

Among the prominent scientists closely involved with the Bulletin is Raymond Pierrehumbert, a lavishly bearded and tweeded physicist, not of the nuclear sort. He joined the magazine’s science and security board while across campus at the University of Chicago. He has since moved to Oxford, but remains heavily involved. In his work on “the early Earth” and planets around other stars, he applies the “same physics we use to quantify the greenhouse effect on Earth,” he told me. “If you’re a climate scientist or paleontologist, you’ve studied the role of CO2 in the Earth’s past history—you know that what humans are doing to the Earth’s climate is truly disturbing.” For his part, he said, “It would be irresponsible to stay in the lab.” Pierrehumbert once wrote a lively column on science and politics for Slate; he also contributed to the website RealClimate and appeared in a well-intentioned rap video titled “We are climate scientists, Chicago style.” (He’s better as a folk musician.)

In a recent cover story for the Bulletin, “There is no Plan B for dealing with the climate crisis,” Pierrehumbert argues in dramatic language against geoengineering. To pursue that strategy, he writes, would commit “generations yet unborn to continuously run a mechanical process, over a time-span longer than the age of the pyramids.… And if our offspring don’t, or simply can’t, do so at some point in the future, then they will suffer the consequences of an unimaginably huge climate shock, accumulated over vast amounts of time.”

When I saw Pierrehumbert at the annual meeting, he was sheepish about the sin of his flight to get to Illinois. Yet he seemed energized by the company of his colleagues: fellow physicists, national-security experts, and politicians, including Jerry Brown, whom he admires. A few years ago, Pierrehumbert told me, he’d raised concerns with Brown about coal exports. If California allowed a proposed coal export terminal to be built, Pierrehumbert had said, it would increase demand in China, putting all of our carbon reduction goals in jeopardy. The problems were confounding, the answer frustratingly simple: “We need to put fossil fuel companies out of business, or at least their traditional business,” Pierrehumbert told me. “We will need to write down carbon to zero.” Brown heard him out, Pierrehumbert recalled, but “it was not on his radar.”

In November, Pierrehumbert had California’s cap-and-trade program on his mind. A flaw of that and related markets, he told me, is that they apply an inaccurate equivalence “standard, mass for mass,” to methane and carbon dioxide, thereby exaggerating the role of methane in global warming. But “if we reopen the debate”—that is, rejigger the math of cap-and-trade—“we could lose the benefit on carbon dioxide. It’s politically complicated. I’m not sure it’s worth the risk,” he explained. “It’s too bad that Jerry Brown is no longer governor.” Even if he didn’t act on everything Pierrehumbert told him about, he had, at least, listened. Gavin Newsom, the new guy in Sacramento, has yet to show up to a Bulletin meeting.

“We want to be read in the White House, at the Kremlin, and at the kitchen table.”

Illustration by Gaby D’Alessandro

At the start of 2020, Bronson and her staff flew to Washington, DC, as they do every January, to announce to the world what time it is. At the press conference, livestreamed to maximize virality, Bronson wore a scarlet dress and stood at a podium bearing the Bulletin’s somber black-and-white logo. In 2018 and 2019, the clock was set at 11:58, the direst assessment by the science and security board since 1953, after both the United States and the Soviet Union tested hydrogen bombs. This year, alongside Brown; Mary Robinson, a former president of Ireland; and Ban Ki-moon, a former UN secretary-general, Bronson delivered an even grimmer report: the world was now a hundred seconds from apocalypse—“closer than ever to midnight,” as CNN would write.

The Bulletin’s accompanying statement, authored by Mecklin and addressed to the “leaders and citizens of the world,” is a seven-page, reader-friendly recitation of man-made horrors and suggested mitigations. Humanity is facing “a state of emergency that requires the immediate, focused, and unrelenting attention of the entire world,” it reads. The reasons are many. On the nuclear side, the US, Russia, and China retain their stockpiles; Iran retreated from international cooperation, in response to America’s withdrawal from their nuclear deal and its assassination of a top Iranian military commander; the INF Treaty is no more and other arms agreements are soon to expire. In terms of climate change, the US officially left the Paris Agreement; Brazil is allowing its precious rain forests to be destroyed; and greenhouse gas emissions are on the rise, zero-carbon rhetoric be damned. All this is made worse by a “corrupted and manipulated media environment” in which truth, let alone scientific reality, becomes increasingly unknowable. Still, the Bulletin statement offers shards of hope. “Climate change has catalyzed a wave of youth engagement, activism, and protest,” it observes. If we multiply this “mass civic engagement,” it states, “there is no reason the Doomsday Clock cannot move away from midnight.”

If the clock announcement invites sober reflection, it’s also an occasion to push for political action. Throughout its history, the Bulletin has balanced its journalistic mission with various forms of advocacy. As soon as the atomic scientists in Chicago founded the Bulletin, they joined with colleagues in Los Alamos, Oak Ridge, and Manhattan to lease an office in Washington, forming a Beltway collaboration that eventually became the Federation of American Scientists. Last year, just after the clock announcement, Bronson, Brown, and former defense secretary William Perry, who now chairs the Bulletin’s board of sponsors, met with House Speaker Nancy Pelosi and Senate Minority Leader Charles Schumer—to lobby not for a specific candidate or bill, but for arms control, diplomacy, and nuclear and climate policies rooted in science. Bulletin staff transmitted the ominous details of the clock statement: North Korean nuclear proliferation, increasing carbon dioxide emissions, and information warfare. This year, alas, Congress was busy with impeachment proceedings.

There is a tension, in such conversations, between fear and hope. How much is too much apocalypse talk? “It’s very hard to find the words, even, to express the moment we now are in,” Brown said, during the clock announcement. “I myself am a person of limitless words, but I can’t find how to say it in such a way that it can be heard.” Back in November, at the end of the closing plenary session, a tall, bespectacled woman in the audience raised her hand: Elizabeth Talerman, a strategic-communications expert, who offered some advice on framing. It’s best to avoid phrases like “existential threat,” she said, because they bum people out. The Doomsday Clock certainly has its skeptics, mostly on the right. See: “Just skip the doomsday predictions, guys” (the National Review); “Goose eggs: No climate change doomsday warning has come true” (the Washington Examiner); “The Climate Doomsday Trap” (the Cato Institute). Strauss, the former editor, told me that the Bulletin has played just as important a role in debunking “overhyped threats”—for example, “fears that terrorists might start massive forest fires”—as it has in playing up actual perils.

When I asked Brown how the Bulletin should convey the urgency of the climate crisis, he didn’t have an easy answer. He brought up a document from 1992, a one-page “Warning to Humanity” published by the Union of Concerned Scientists, a nonprofit whose members and staff often write for the Bulletin. “A great change in our stewardship of the earth and the life on it is required, if vast human misery is to be avoided and our global home on this planet is not to be irretrievably mutilated,” the statement reads. Brown’s point was that every climate messenger, not just at the Bulletin, struggles to balance gloom and motivation. Meaghan Parker, executive director of the Society of Environmental Journalists, told me, “It’s not so much about the emotion—are you a doom writer or a solutions-and-hope writer?—but talking about the specific, lived changes of real people.”

Some Bulletin articles punch and flail; others coax. Many do both, traipsing from seemingly intractable problems to optimistic solutions. In its March 2019 issue, the Bulletin examined “climate change action—from the right,” including an interview with Christine Todd Whitman, the former governor of New Jersey and head of the Environmental Protection Agency under George W. Bush, and an article about a Christian group, Young Evangelicals for Climate Action. Mecklin’s editor’s note offered practical guidance to “ungenerous corners” of the American left: “Republican officeholders are not likely to agree to substantive action on climate change until they feel it is clearly in their best political interest to do so. The best people to explain those best interests to Republican congressmen and women? Republicans who believe in climate action and vote their beliefs.” Recently, when I sat down to read a tall stack of Bulletin articles, I felt a confusing combination of terror, depletion, and productive rage.

Perhaps this is how the original atomic scientists felt, trembling from guilt, trying to pull us away from the abyss. Nuclear war, so overwhelming a concept, once needed its own metaphors to be understood. When the Bulletin first took on climate change as an area of focus, it might have seemed an odd fit. “As they say, nuclear can do us in in an afternoon; climate change will take much longer,” Kennette Benedict, the Bulletin’s former director and publisher, who oversaw the inclusion of climate change in the clock-setting, told me. But the two crises are now an inseparable apocalyptic pair. If memories of fallout shelters and air raid drills make rising sea levels and extreme temperatures feel more pressing, then so be it.

E. Tammy Kim is a freelance reporter and essayist whose writing has appeared in The New Yorker, the New York Review of Books, the New York Times, and many other publications. She coedited 2016’s Punk Ethnography.