You begin by teaching yourself what you can ignore. Rot in hell. You’re a cunt. Maybe you wouldn’t be so mad if you weren’t so ugly. They arrive as replies on Twitter, a line dropped into a DM, comments reassuring in their lack of specificity. The reasons they arrive are not always clear. The first time I was told I should go die a slow and painful death, it was because I had written about Kristen Stewart. I’d posted on a small WordPress blog, and a female fan had disliked the way I’d analyzed her star image.

Most of it arrives online—through Twitter, via personal Facebook messages, on Instagram, through email exchanges, and sometimes even in our parents’ inboxes. When ignored, these threats can sharpen and multiply. What begins as displeasure with a piece can escalate to confrontations that are chilling in their cruelty. Abuse and menace have become a way of life for women in journalism. But like so many things in women’s lives, the labor of confronting that menace is largely invisible.

ICYMI: The Wall Street Journal unleashes a bombshell report

Abuse can also manifest itself in invisible ways: In the stories that have gone untold or unexplored by women because the risks of telling them, psychologically or physically, require too damn much. Most editors don’t understand the extent of the abuse—why would they? They don’t read our inboxes or track our direct messages, they can’t assess our fear as the responses mount, weighing the validity of each threat alongside the daily back-and-forth of reporting. Depending on their own identity, they don’t know the complex matrix of decisions women make in the field to render themselves less threatening, or the thought put into how and who to block, report, or ignore online.

I spoke to several women about how this kind of harassment affects their work as journalists, and while many started the conversation saying they didn’t deal with threats on a daily basis, they ended by telling me intricate strategies they’ve developed for shielding themselves from it online. They’ve defused situations where their very status as a female reporter—asking questions, being in public—made them vulnerable. It’s exhausting to try to experience the reporting world from the same place of safety as a straight white man, but female reporters, especially minorities and those who identify as queer, often forget how many things are making us tired—and making our jobs so much harder.

In 2015, Julie DiCaro was covering rape allegations against Patrick Kane, a hockey player for the Chicago Blackhawks. A reader took a picture of the side entrance she used to enter her workplace and sent it to her. “If someone’s willing to go through all that trouble,” she tells me, “what else are they willing to do?” When Scaachi Koul, currently a culture writer for BuzzFeed, was covering the sexual assault trial of CBC Radio host Jian Ghomeshi in Canada, commenters began to go after her preschool-aged niece, who is biracial, calling her a “mutt,” and criticizing her family for bringing a white person into their family. When Soraya McDonald wrote a piece for ESPN’s The Undefeated that was critical of Floyd Mayweather, she was asked if she was “tap-dancing for the man.” And when Nadra Nittle was covering education for the Los Angeles Newspaper Group, she started receiving messages about “vengeance” from the spouse of the principal of a school she’d covered.

“My editor was like, don’t worry about it,” says Nittle, who now writes for Racked. “But I let my husband know. I let my sister know. I let the school district know. I had to let them know there was a pattern of behavior.”

Nittle touches on three themes of reporting as a woman: First, you teach yourself to downplay whatever threat there might be. (“I didn’t feel like my life was in danger, necessarily,” she tells me.) Second, you tell people about the actual menace, so you have a record of your concern. And third, you realize your supervisors may or may not have the same level of concern, or first-hand exposure, to the threats you face. Whether such threats are viable matters less than their intent: to make women feel more vulnerable, and to use that vulnerability to make them question their work as journalists, a job that is itself under threat.

In 2013, Nittle was reporting part of the Zip Code Project, a large-scale documentation of areas of Los Angeles. “I was assigned to one of the middle-class neighborhoods,” Nittle tells me, “and one of my editors asked me to take video. I had this moment, walking around the neighborhood, in the middle of the day. I don’t want them to think, ‘Oh, here’s this black person, what is she doing filming in this neighborhood?’”

ICYMI: Former New York Times journalists are furious

Solitariness, as Nittle points out, makes it more difficult to “announce” yourself as a press. It also immediately marks you as more vulnerable—especially when you’re reporting as a freelance journalist. Staff journalists, after all, have infrastructure in place (editors, security teams, offices, co-workers) that, depending on the assignment, keep tabs on a journalist’s location, monitor any harassment she receives, and put security measures in place when necessary. There are people, in other words, looking out for her in some capacity. A freelancer operates largely on her own, oftentimes reporting a story on spec before bringing it under the umbrella of an organization that could help shield her.

Liana Aghajanian reports internationally, often in places the mainstream media doesn’t cover, on issues of immigration, identity, and culture in the United States. When she plans to report in an area where she wouldn’t feel safe, she brings her partner along. “I know that because he’s there, I’ll just feel more protected—and I’m able to do things other female reporters can’t do.”

“I’ve started to think about what it means to be a freelance female journalist on a whole other level,” Aghajanian continues. “You associate it with being something dangerous and risky, but the risks are around us in ways that we don’t actually know yet. You want to be like, yes, this is so cool, they’re going to let me into their world. But now you have to think: Is that person going to harm me? Is that person going to put me in a situation where my life is at risk? That makes you more cynical. And especially with my work, and the sorts of topics I like to pursue, if I become more cynical, my work is going to suffer.”

Abuse can manifest itself in the stories that have gone untold or unexplored by women because the risks of telling them.

When I pitched my editors at BuzzFeed earlier this year the idea of moving my beat from New York City to Montana, it was in hopes of avoiding that sort of cynicism, while also benefitting from my small-town Idaho upbringing. People from rural areas are skeptical of anyone from cities, and doubly skeptical of reporters from them. But being from “around here” has many benefits: I know how to talk to just about anyone. I also know exactly how to make myself as unthreatening as possible.

Molly Priddy’s been a specialist in this sort of reporting for nearly a decade. She covers what she refers to as “women’s issues” for the Flathead Beacon, a weekly paper funded by Maury Povich and Connie Chung out of Kalispell, Montana. “I have this nebulous social issues beat,” she tells me, “in part because I’m the only woman on staff.”

Illustration: Ellen Weinstein

“In a place like Montana, you never need to be intimidated by who you’re talking to,” Priddy says. “Talking to the governor is the same as talking to the farmer down the road. It’s never intimidating unless you’re in a crowd, where everyone’s carrying and telling you to buy silver,” a hallmark of a particularly Montana brand of libertarianism.

“When I was younger and had longer hair, I played into the ‘oh you’re teaching me,’ bit,” Priddy says. She’d show up at legislators’ offices and allow them to think she, herself, wasn’t a journalistic threat. “But now that I cut my hair short and started presenting less femininely, I get treated a lot more brusquely.” She quickly learned how best to disarm people. “Women learn it early on: the placating-predator-smile. The ‘I think you’re a good man, aren’t you a good man who would never hurt me?’ smile,” she says.

In truth, I learned that smile a long time ago: The first time I challenged a male teacher in the classroom, the first time I ran into a pair of men in the wilderness while I was out hiking alone. But it’s been put into practice many times since becoming a journalist: at Trump rallies across the nation, when I was pulled over by two state patrolmen outside of Standing Rock, asking questions about Obamacare inside a taxidermy shop in a small Montana town. Times when some combination of my smile—along with my whiteness, and my blonde hair, and my Idaho driver’s license—not only protected me, but ingratiated me.

Priddy’s particular safety is also a matter of local specificity: Most residents think she’s on their side. “Frankly, people up here in the Flathead, they don’t trust the mainstream media, but they do trust the Main Street media. We’re not seen as ‘the media,’ we’re just Beacon reporters. I was born and raised in Montana, so that helps. I know about firearms. I hunt and fish. I come from a military family, so I can find a traditionally masculine conversation thread which changes the tone. It becomes, ‘Oh, she’s Montanan, not a lady reporter here to fuck up my life.’”

Priddy acknowledges that here in Montana, which is 89.5 percent white, her own whiteness protects her from the kind of threats that make it far more difficult for reporters of color to do their job. Other white journalists were quick to point out that whatever threats they might experience, there were areas where their whiteness not only made them safer, but made their jobs easier. Annie Gilbertson, an investigative reporter for KPCC in the Los Angeles area, told me that when she was covering education, she was able to walk onto public school campuses with ease. “No one would question why I was there, or whether I was a threat,” she says. “That isn’t afforded to someone who doesn’t look like me.”

“I don’t know how any woman of color can have their DMs open,” says Imani Gandy, who works as a legal journalist for Rewire, focusing on reproductive justice. When she publishes a piece she knows will go viral or press buttons, she activates Twitter’s “quality filter” that makes it so she can only see comments and replies from people she follows.

Gandy practiced law for a decade before starting her blog, Angry Black Lady, as a way to bring together the threads of social and reproductive justice that mattered to her—and build a following robust enough that she could quit her day job. Her blog’s name stems from a pituitary gland condition whose major side effect is massive mood swings, but when she started to get into political Twitter, it began to fit the rest of her brand. “No one’s going to accuse me of not having an opinion,” she tells me.

Those opinions made Gandy’s online life (and necessarily, her life) difficult from the beginning. A person has stalked and harassed her for five years based on a blog post she wrote in 2012. Other commenters call her the N-word and a “cunt.” One man devoted two years to creating new Twitter accounts every day with the sole purpose of harassing her. She’s been told she’s not really black because her mom is white—that she’s posing as a “quasi-Negro.” Her medical condition has been questioned, as have her credentials.

“I’ve also gotten over the notion that I need to be open to engagement with everyone,” she says. “I see white guys saying, ‘you really need to follow people you disagree with,’ but they don’t spend all day being attacked just for their identity. If they got harassed as much as I do, they wouldn’t last a day.”

“Feminist female writers have always known this is an issue,” explains Koul. “But something happened two years ago, with the ramp-up to the election: If you were a female writer, you couldn’t say something without someone wanting to kill you. It shifted our understanding of a threat.”

Koul, who lives in Toronto, has been pissing people off since she first began writing on the internet: for Maclean’s, for Hazlitt, and, most recently, for BuzzFeed, where she focuses on the intersection of race and culture, broadly speaking. Koul’s threats largely come from men’s rights activists, Indians mad that she went after Jian Ghomeshi, and members of the Canadian media. Unlike the vast majority of women I spoke with, Koul prides herself—and has, in some sense, made her name—on fighting her trolls.

Threats make women feel more vulnerable and question their work as journalists, a job that is itself under threat.

Koul’s posture is unique because it goes against general industry wisdom not to “feed the trolls,” as responding only authenticates and emboldens their existence. But ignoring them can also feel incredibly passive: Abuse happens to you; you’re the “target” of abuse. Responding can oftentimes feel like regaining dominion over the rhetoric that surrounds you.

When Koul receives a comment intended to shut her up, she just talks more. “If you’re coming to me on Twitter or in my inbox, you’re coming to my home. If you’re telling me, for instance, that I only got my job because I’m a diversity hire, I will guarantee that you will leave the interaction with the sensation of your testicles slowly leaving your body,” she tells me.

ICYMI: A school district kept a secret blacklist for decades. A reporter found it.

Ashley Lopez, who covers the intersection of health and politics for KUT, an NPR station in Austin, Texas, regularly receives negative, often personal pushback online, especially when she writes about abortion. She used to block or mute those who went after her. When one account’s comments began to resemble death threats, she didn’t even see it—her colleagues did. When she brought the tweet to the attention of law enforcement, they advised her to stop muting accounts: She needed to be able to actually see when she received death threats. So now she just lets what would once have been muted flow over her. But she refuses to allow it to affect what she will and won’t cover. “If there’s a story that I need to do as a journalist, I’m going to do it,” she tells me. “Just because I’m a woman, or I’m Hispanic—it doesn’t matter. Because I’m not myself when I’m reporting.”

“I’ve had people ask me if I were ‘legal’ during a conversation,” she says. “If someone asked me that at a bar, I would lose my mind. But this person was taking the time to talk to me when they didn’t have to. I wasn’t Ashley in the moment. I was just trying to have a conversation. This is why I find being a person more exhausting than being a journalist: There are rules that I follow as a journalist.”

But women, journalists and not, know that you can follow all the rules, put in all the work, set all the boundaries—and things can still go terribly wrong.

Kim Wall, a 29-year-old graduate of the Columbia Journalism School, told the sort of expansive, probing stories that people dream of when they imagine the life of an international freelance journalist, looking at the creation of an internet-free culture in Cuba, the tiger-poaching industry in India, and the regulation of pornography in China. Her reporting is filled with what we might call “characters”: furries, topless painted ladies in Times Square, real-life vampires, plus-size pole dancers, the sort of “places and people that did not conform and were frowned upon if they stood up for themselves,” recalls her friend and reporting partner Caterina Clerici in an essay for The Guardian. Wall took calculated risks with her work, as do the best journalists.

Last summer, Wall, a native of Sweden, happened upon on a very Kim Wall sort of story: A Danish inventor named Peter Madsen had set to build his own space rocket. As Wall learned more about him, she also found out that he’d built his own submarine. In August, he agreed to meet her in Copenhagen for an interview on board. It would be the perfect setting for the sort of profile at which Wall excelled.

She never returned. Eleven days after her disappearance, her torso washed ashore. Madsen claimed that Wall had fallen down a set of stairs, but an autopsy revealed that she had been stabbed numerous times, including at least 14 wounds to her genitals. Footage of women being tortured and mutilated was also found on Madsen’s hard drive.

The story of Wall’s death circulated swiftly through the journalism community. It was gruesome, unspeakably tragic, a nightmare, as if all the threats from our inboxes and Twitter feeds came to life, but with the promise of a really good scoop or the makings of a killer lede. “Every independent journalist I know would have put herself or himself in that situation,” writes Clerici, “pre-reporting what sounded like an extremely quirky, complex, and challenging story.”

Clerici argues Wall’s death should not be used to blame women or exclude them from this sort of reporting. But it does reanimate the fears many female journalists swallow or otherwise suppress. Aghajanian knows the feeling. “When you read about Kim Wall, your worst fears get confirmed. I think back to every situation I’ve been in, even in the US: getting into a car with someone, visiting someone in their home. Every instance is one where what happened to Kim could happen to you. As journalists, we all want access. We want to go in that submarine. But at what risk do we get that access?”

It’s not that women can’t get this sort of access—journalism has never been a matter of being able to do it. We know how to navigate every encounter with an unknown man with the quiet thought that it might lead to violence. We figure out how to delete or ignore or make light of the emails that arrive in our inboxes. We learn how to deal with the way menace accumulates through the course of our daily workload. We know how to perform all of that labor—and, like so much other labor largely performed by women, to make its existence, and its toll, disappear. The question isn’t our capacity to do it. The question is, at what cost?

Nothing new

Over the course of nearly 200 years, female journalists have been under threat because of their gender, race, beat, views, and coverage.

1829 Travel writer and newspaper editor Anne Royall was charged and convicted of being “an evil-disposed person and a common scold and disturber of the peace and happiness of her quiet and honest neighbors” following a string of altercations with local DC clergymen. Royall avoided punishment, which at the time was “a dunking,” because the judge considered it too medieval.

1850 Journalist, activist, and the first black woman publisher in North America, Mary Ann Shadd Cary fled the US and moved to Canada with her family after the passage of the Fugitive Slave Act to escape the threat of unlawful enslavement.

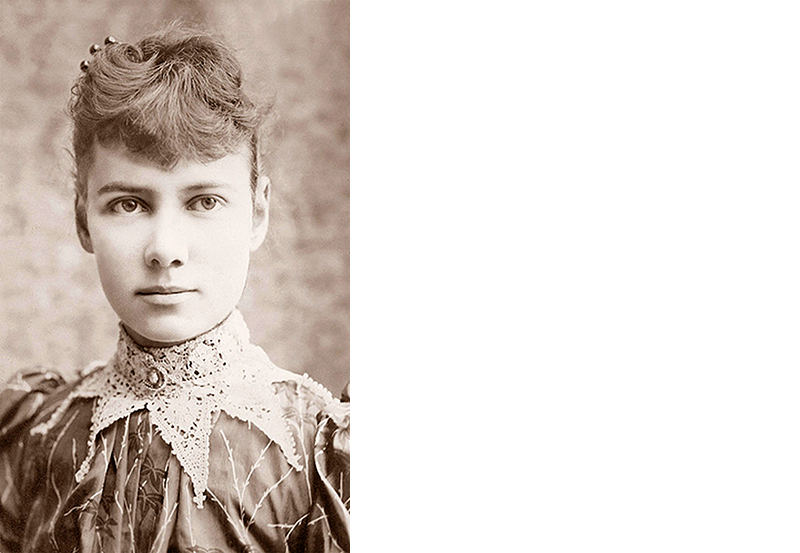

1887 While undercover in an asylum for an assignment, pioneering investigative journalist Nellie Bly experienced the horrific conditions of the institution firsthand and had difficulty getting out. (The New York World’s lawyer had to negotiate her release.) “My teeth chattered and my limbs were goose-fleshed and blue with cold,” she wrote of the experience.

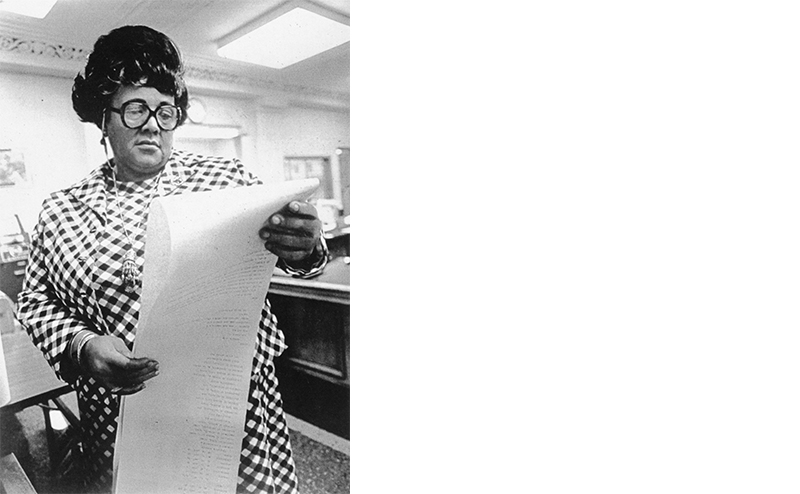

1892 Ida B. Wells—journalist, civil rights activist, and co-founder of the NAACP—received countless death threats when she wrote an article denouncing lynching in The Memphis Free Speech, the newspaper Wells owned at the time. Angry white residents, who destroyed the offices, left her with little choice but to leave town.

1937 Having reported on almost every major international conflict, Martha Gellhorn routinely put herself in harm’s way. Reporting from Madrid on the Spanish Civil War, she wrote: “Every night, lying in bed, you can hear the machine guns in University City, just ten blocks away.”

1939 Margaret Bourke-White, a photojournalist and war correspondent, came under fire in Italy and other combat zones while documenting World War II, eventually becoming known as “Maggie the Indestructible” by her Life colleagues.

1954 White House press secretary James Hagerty explored ways of revoking journalist and civil rights leader Ethel Payne’s White House press accreditation after she pushed President Eisenhower on segregation and racial inequality.

2006 A controversial figure, Italian journalist Oriana Fallaci received several death threats and lawsuits for vilifying Islam in her writing, in which she vowed to blow up a mosque.

2006 Russian journalist and human rights activist Anna Politkovskaya received countless threats of rape and death before being assassinated in Moscow in 2006. Her critical reporting of the Chechen conflict and Vladimir Putin has been cited as the motive.

2012 While covering the siege of Homs in Syria, American journalist and war reporter Marie Colvin was killed when rockets were fired at the house where she was staying.

Anne Helen Petersen is a senior culture writer and Western correspondent for BuzzFeed News. She received her PhD in media studies from the University of Texas, and her most recent book is Too Fat Too Slutty Too Loud: The Rise and Reign of the Unruly Woman.