About a hundred miles from New York City, among the trees in East Hampton, Long Island, sits the Ross School. Started in 1991 by Steven Ross, who founded Time Warner, and in larger part by his wife, Courtney, as a tutoring group with extravagant field trips, today the school is a campus of glass and stone. In attendance are some 450 day and boarding students from across Long Island and around the world, in kindergarten through 12th grade. In front of the high school building, at the back of campus, is a reproduction of the Winged Victory flanked by a fountain.

One day in November, students in navy blue and khaki uniforms filed into a classroom in the basement. Their chatter was multilingual—English, Czech, Chinese, German. The teenagers, in grades 9 through 12, took their seats at three tables arranged into a U. Their teacher, Paul Gansky, 33, wore a gray blazer and a button-down with brightly colored stripes. He carried a jade-colored teacup. (“It’s a Fire-King milk glass,” he says.) His students call him Paul.

Gansky directed everyone’s attention toward a projector screen displaying an image of a factory—row after row of bright-yellow machines with robot arms—belonging to Foxconn, the Taiwanese electronics manufacturer. This was the Apple supplier in Shenzhen, China, that, several years ago, earned significant media attention when China Labor Watch reported on conditions there. After a quick review of the report (it was a survey of a small number of workers, Gansky explained, and those who spoke about their experiences did so at significant personal risk), Gansky asked the class how much workers tasked with assembling laptops should be paid. “What would be a fair wage? How many hours do you think it would take to assemble a single computer?”

Hands shot into the air. Estimates varied widely. Luisa said $70 an hour; Cristina suggested $8 and change. Katharina, a boarding student from Germany, said that assembling the computers required skilled labor. “So I would expect a good wage,” she explained.

Gansky pulled up the real numbers. A student, visibly shocked, whispered “Fuck!” under his breath. According to the 2012 report that Gansky had in hand, workers at the Foxconn factory in Shenzhen earned $250 a month—less than $2 an hour—and paid up to $18 for dorm rental as well as fees for the privilege of having been given an opportunity to interview for the job. The class scribbled notes: on hundreds of workers sleeping on cots in a single room, on the dangers of working with copper, on what low-level radiation and excessive heat do to the body, on suicide rates. Gansky encouraged the students to consider why Foxconn might insist that its workers use banana oil, which is toxic, to polish screens before they’re packaged and shipped around the world, erasing fingerprints “as if nobody built this machine at all.”

The class, e-commerce, an elective, is a component of the Ross media literacy program, aimed at teaching students not just how to consume and produce different types of media but also how to interrogate a narrative—how to pick it apart, flip it around, and inspect it for flaws that its makers worked hard to conceal. Over decades, Ross has set scholars on the task of crafting its curriculum, with ample resources—annual tuition is $72,800 for boarding students, $41,200 for day—yielding a sophisticated approach reminiscent of graduate-level programs. The result is a scholastic counterpart to the refinement of the Hamptons, an area known for its beachfront mansions, luxury cars, and elite social scene. (Alexa Ray Joel, daughter of Billy Joel and Christie Brinkley, attended the Ross School, as did Scott Disick, onetime love interest of Kourtney Kardashian, among other children of the Hamptons upper class.)

For Gansky, the decision to tackle media literacy as part of an education in the culture industry at large—with attention paid to journalism as well as film, advertising, video games, and other kinds of storytelling—is about restoring a sense of political agency lost in the hyperpolarized world in which Ross kids live. His most effective message to the class is “You guys are living in a sort of media narrative that’s been designed for you,” he tells me. “And they kind of perk up across the board, whether we’re people who read news or who play Fortnite. That’s when you start to see, across nationalities, folks begin to go, ‘I can interrogate that. My video game is actually worth analyzing the same way that a news article is.’ ”

The next day, the class watched a segment of a documentary about Shenzhen produced in 2016 by Wired magazine as part of a series called Future Cities. Before Gansky hit play, he asked his students to predict what information from the China Labor Watch report might appear. Liam Murray, 17, suggested that American income stagnancy—and with it the fight to raise the minimum wage—might be offered as a point of comparison for US viewers, to encourage empathy for the low-paid employees of Foxconn. “American viewers familiar with disappointments in wages could relate,” he said. Harlan Beeton, 18, thought the filmmakers might try to make an explicitly political statement, exploring what the US and Chinese governments were doing to combat the human rights offenses the class had discussed a day earlier.

But the beginning of the film offered none of that. Instead, it was a glossy introduction to Shenzhen: the camera sweeps through a busy market where salesmen offer iPhones, tablets, and the tools needed to take them apart. Drone shots ogle a crowded, booming metropolis, its buildings fitted together like Legos. “Oh my gosh, I love Shenzhen,” a man says. “You can’t talk bad about Shenzhen.”

About 10 minutes in, Gansky hit pause and turned on the lights. He wanted to talk about what the class had seen so far—and what it hadn’t. “Our students are coming from incredible privilege, and many of them end up writing New York Times best-selling books, or they end up being editors at major newspapers, or at places like CNN, or they become film producers,” he tells me later. “They have a real leg up in terms of where they’re going to be in the culture industry. I want them to know, as producers, that they need to take the same sense of critical analysis to the projects that they deal with as professionals. Because they’re setting the discourse. They’re really shaping how our country thinks of itself.”

In the wake of the 2016 elections, lawmakers, aghast at the prevalence of “fake news”—outright lies designed to look like legitimate information—sprang into action. States began adopting legislative fixes. In Rhode Island, Governor Gina Raimondo signed two bills mandating that the state’s education department consider adding media literacy to its curriculum. In Washington State, the superintendent of education conducted a media literacy survey and launched a website enumerating practices for incorporating relevant lessons into curricula. Similar bills have been introduced or passed in Connecticut, New Mexico, California, Hawaii, Arizona, Massachusetts, New Jersey, New York, Pennsylvania, and Texas. Internet resources like Snopes (a fact-checking site), FactCheck.org, and Common Sense Media’s Digital Citizenship curriculum are being adopted for use in classrooms all over the country. The dizzying election cycle that delivered Donald Trump the White House heightened America’s media-related anxieties, giving them tangible form. The need to devise a solution became urgent. “Now it’s about mobilizing students,” Gansky tells me.

But media literacy has been on the minds of educators for generations. When, on October 30, 1938, Orson Welles broadcast The War of the Worlds, a radio account of a fictitious alien invasion, and caused panic in American households, the public came to understand the technology’s dark potential. The extent of the hysteria has since been called into question—media historians note that newspapers, eager to discredit the new medium cutting into their ad revenue, grossly exaggerated the reaction; even so, the broadcast sparked concern about radio’s application in the widespread dissemination of propaganda. Scholars began to study radio’s impact; a group of researchers, teachers, and journalists founded the Institute for Propaganda Analysis (IPA) at Columbia University. In a 1939 report, Howard Cummings, an IPA researcher, wrote of a need to teach the public “general habits of analysis” and “attitudes of skepticism.”

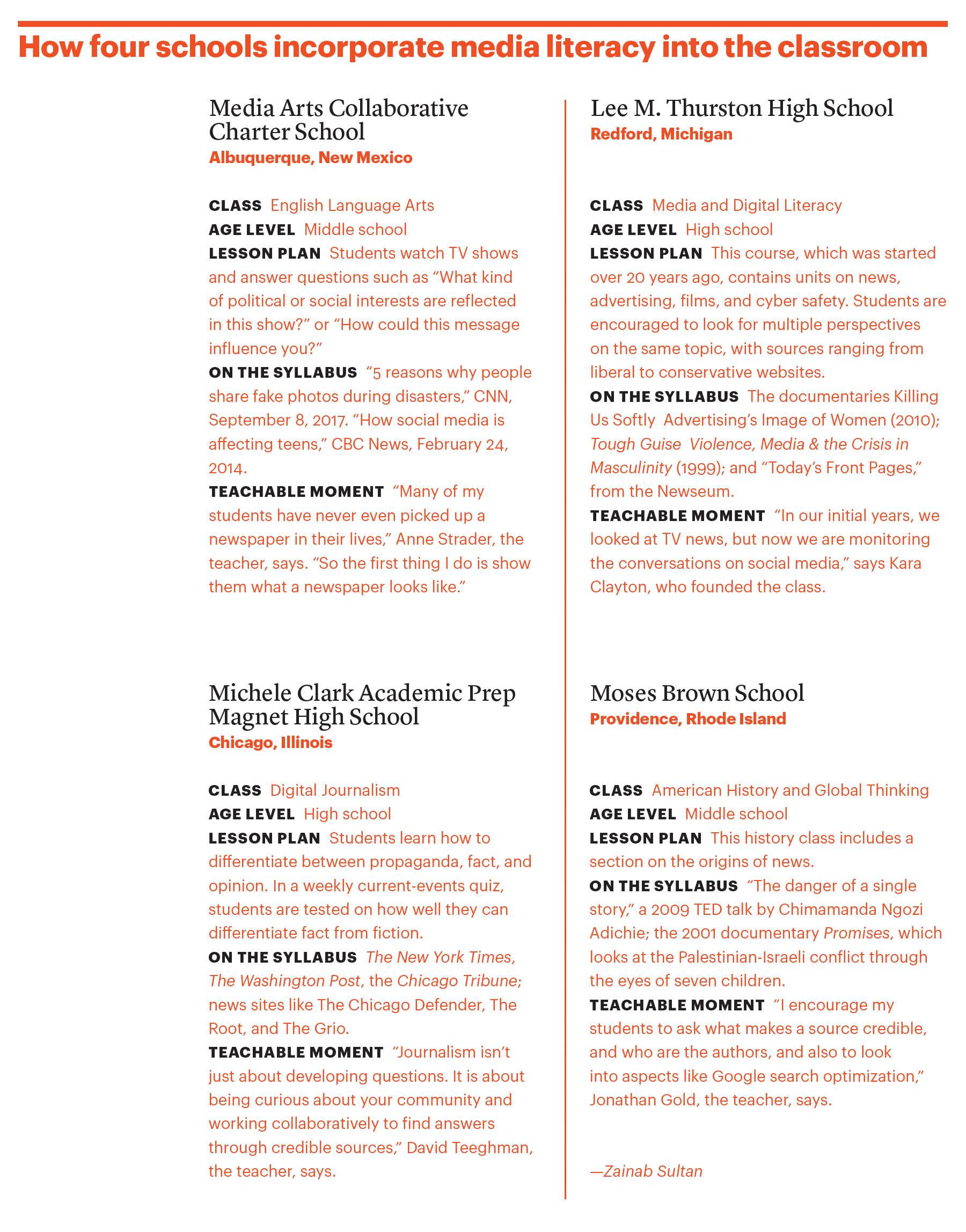

Paul Gansky, left, and Marie Maciak, right, helped develop an innovative curriculum that rivals graduate programs. Photo by Matthew Septimus

In addition to researching how public opinion is influenced, the IPA promoted study groups in public schools that would teach children how to identify propaganda. Edward Filene, the department store baron, funded the institute and, working with Clyde Miller, a former reporter at the Cleveland Plain Dealer and a faculty member at Columbia’s Teachers College, gave more than $1 million to create what was essentially a media literacy curriculum. Miller oversaw the publication of articles with such titles as “How to Detect Propaganda” and “How to Analyze Newspapers.” The materials were shipped to thousands of teachers, librarians, and college professors.

In the fifties, as television came to the fore, teachers adjusted their efforts to suit a new generation of kids. In 1964, Marshall McLuhan determined that “the medium is the message” in his book Understanding Media, which turned up in classrooms all over. During the seventies, Elizabeth Thoman founded an influential magazine, Media & Values, that would lead to the opening of an organization called the Center for Media Literacy. Eventually, focus landed on the production of media, including film. The eighties and nineties ushered in cable television and the so-called 500-channel universe. Media literacy emphasized the minimization of harmful messages that could be delivered through TV (sexism, racism, violence).

By the following decade, legislators were receiving complaints, spurred in part by the religious Right, of violence in the media. “Media literacy came up again,” Renee Hobbs, part of a fledgling group that would soon become the National Association for Media Literacy Education, recalls. “We all got to go to Washington to meet with President Clinton and talk about media as prevention strategy.” Broadcasters, in an effort to avoid congressional regulation, created educational programming focused on health and crime prevention.

While Congress aired concerns about violence in media, agents of the state could be seen on camera brutalizing people. Hobbs, a professor of communications at the University of Rhode Island, made a documentary instructing viewers in critical analysis of the distressing scenes they saw on the news. Called Tuning In to Media, it examined coverage of Rodney King, a construction worker in Los Angeles who was beaten by police, and the riots that ensued in response. She sought to prevent desensitization—a goal that has not become easier to achieve in the years since. “The fact that the media is always changing means media literacy is also always changing,” Hobbs tells me. “It’s a moving target.”

When Courtney Ross wasn’t in the Hamptons, or at her home on Park Avenue, in Manhattan, she was traveling the world with her daughter, Nicole, whom she homeschooled. The experience, Ross realized, was an opportunity to help her child make connections across subjects and cultures. Soon, she started bringing along Nicole’s friends; after Steven died, of cancer, in 1992, she became an “edupreneur,” pouring more than $330 million into building the Ross campus. To formalize the academic offerings, she tapped her extensive network of accomplished friends; in 1995, William Irwin Thompson, a poet and historian, and Ralph Abraham, a chaos theorist, developed the “spiral” curriculum, which thematically links all subjects into a narrative telling “the evolution of human consciousness.” During those early years, the school was for girls only and had no class periods; learning would not be circumscribed by arbitrary limits on time.

It follows that instruction in media literacy at Ross was always highly experimental. That’s thanks in part to Marie Maciak, a documentary filmmaker the school hired in 1996 (along with a Tibetan monk and a Maasai warrior, both scholars in residence). She came to capture the school’s attempt at building a learning environment that would, in Courtney’s terms, produce “global citizens.”

“In my early years at Ross this was a very vibrant community where people were coming in and discussing current events and issues that, in their specific fields, were cutting-edge, and seeing where those issues fit in a K–12 education,” Maciak tells me over lunch in the school’s Center for Well-Being (it houses the gym and a cafeteria that rivals those of corporate offices). One day, a group of students approached her in the studio on campus where she edited her work, curious about what she was doing. “Interest grew,” she recalls. “Within a year I was asked to set up a proposal for integrating media into the curriculum.”

Maciak suggested a focus on “construction and deconstruction”—teaching kids how to make media, evaluate it, and use it to effect change. Working with people like Goldie “Red” Burns, the founder of New York University’s Interactive Telecommunications Program at the Tisch School of the Arts, Maciak began to build an outline. “We started to lay out the structure of how we can ensure that kids are empowered to produce their own messages but can also think critically.”

The message to Ross students is: “You guys are living in a sort of media narrative that’s been designed for you.”

Over the years, Maciak tailored her students’ media projects to align with themes they were learning about in other classes, like social studies. In the early aughts, Ross’s fifth graders were studying ancient Sumer, so Maciak gave out assignments connecting that region to current events. “We were talking about the upcoming possible bombing of Iraq, and kids were very active,” she says. “Kids were protesting, were making PSAs.” Maciak, who had been working on a film about refugees in Syria, connected her class with a group of Iraqi children living in Damascus. Using Skype, the students collaborated on a project: those in Syria would write a play about their experience, and those at Ross would perform and record it for them. They Skyped back and forth, sometimes working on the script (with help from an interpreter) and sometimes just talking.

Technological advances forced changes in how Ross approached media. Cameras became smaller and less expensive, which made production appealing, but the long blocks of time needed for kids to edit footage were impractical for a school schedule. (By this point, periods had been introduced.) Classes that focused on filmmaking became electives or independent studies. Today, Maciak explains, “In the courses that are mandatory, we put the whole focus on understanding how media functions—media consumption issues, ownership.” Students are asked, “Who created this? What is their agenda?” They look at conventional outlets, such as the Times and CNN, and turn to resources like Democracy Now! and Fairness and Accuracy in Reporting (FAIR), a media watchdog group.

Photo by Matthew Septimus

Gansky, originally from Colorado, received a PhD in media studies from the University of Texas at Austin and arrived at Ross in 2016. Reflecting on his period immersed in scholarship, he recalls, “The big focus at that time was moving away from areas where mass audiences were constructed for television and radio, and into these more complex and, in some cases, much more insidious realms.” One of his professors was especially interested in Alex Jones, based in Austin, who for years had been broadcasting conspiracy theories via InfoWars, his multimedia company. “It was really hair-raising to see how he weaponized information,” Gansky says. “He wanted to reach a certain audience, to create extremism in the discussion for that audience, and he really couldn’t care less about any sort of empirical truth. I was totally hooked.”

Gansky took a teaching job at Ross—a place that he says has both the money and the “political chutzpah” to prioritize a serious media studies program—and worked with Dan Roe, formerly a teacher and now the school’s communications director, on writing an updated media literacy curriculum. The framework would be based on an exploration of “persuasion—how thoughts, actions, and speech are transformed or engineered,” Gansky explains, and would feature both production and critical-studies tracks. It would be intended for students in every grade; by high school, he says, students are “ready to consider the fact that reality is constructed.”

The embrace of a theory-heavy approach—“My influences are primarily Natasha Dow Schüll, Jonathan Sterne, Paul Lazarsfeld, and Elihu Katz,” he says—is unusual for children. Students frequently work with news articles and film, but their conversations go much further than simply identifying material as credible or not. After Gansky’s class watched the Wired documentary, Murray, who has been a student at Ross since grade 9, told me how his perception had shifted: “I was expecting to see an exposé, like, Oh my god, look at this horrible thing.” Instead he found himself musing about Wired’s interest in portraying Shenzhen in a certain way. “Wired is a company that benefits off of every electronic that those sorts of companies produce,” he said. “When I first thought about what I was going to see, I didn’t take into consideration that it was Wired, a tech magazine. I didn’t really think about how they’d frame it. Then as I’m watching this, I’m like, ‘Of course. China Labor Watch are the ones putting this information out. So Wired doesn’t really have an obligation to say, Look at this terrible thing happening.’ ”

Until recently, so-called digital natives—children born after computers and cell phones became ubiquitous—were assumed to be better equipped than their parents to parse the constant flow of information. But kids, supposed masters of the screen, tend to be novices at interpreting the information they are so adept at sharing. Meme culture on social-media platforms like Instagram and Snapchat, where huge numbers of young people convene, further complicates matters.

In 2015, researchers at Stanford University’s History Education Group set out to measure what they called “civic online reasoning,” the ability of young people, from middle-school to college age, to assess the credibility of information they consume on the internet. The group evaluated 7,804 student responses to 56 media-related tasks in 12 states. The goal was not to ask participants to make murky distinctions about the best answers to questions. Instead, the group set a series of what they believed to be reasonable benchmarks: For middle schoolers, the hope was that they’d be able to distinguish between a news story and an advertisement. The researchers hoped that high school students reading about gun laws would notice that the origin of a chart was a political action committee for gun owners. And by the time students reach college, the researchers thought, they should look askance at a website with a “.org” URL that focused on just one side of a contentious subject.

“But in every case and at every level, we were taken aback by students’ lack of preparation,” the researchers wrote in 2016, when the first results were published. Over 80 percent of the 203 middle schoolers surveyed believed that native advertising—even when labeled “sponsored content”—was a legitimate news story. The high schoolers, meanwhile, were asked to examine a website on the minimum wage that included links to news articles published by the Times; the site was managed by the Employment Policies Institute, which self-identified as nonpartisan. Only 9 percent of students enrolled in an Advanced Placement history course could correctly identify the group as a front for a conservative DC-based lobbying firm. (A quick Google search of the organization’s name pulls up several trustworthy results identifying it as such.)

By the end of high school, Gansky says, students are “ready to consider the fact that reality is constructed.”

Later, 25 undergraduates at Stanford were asked to spend 10 minutes examining two websites: that of the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), a trusted group with an 88-year history, and one for the American College of Pediatricians, a fringe organization classified by the Southern Poverty Law Center as a hate group for its stance linking homosexuality to pedophilia. The students were asked to determine which site was more credible. More than half chose the American College of Pediatricians and, even among those who selected the AAP, most spent their time on the organizations’ websites; they failed to venture out and independently investigate details about the groups before making a judgment.

News outlets have lamented a decline in trust from adult readers, but kids, unable to reliably interpret information online, don’t engage with credible journalistic outlets either. In December, a Knight Foundation survey of high school students found sharp drops in teen news consumption: just 14 percent of high schoolers said they “often” watch their local TV news stations, compared to 30 percent in 2016; 12 percent reported watching cable news often, a fall from 26 percent.

Even engagement with news on social media, where teenagers spend hours daily, dipped from 51 percent in 2016 to 46 percent in 2018. The proportion of respondents who said they “hardly ever” share news articles on their time lines jumped from 53 percent to 64. Eighty-one percent said they hardly ever talk about news at all.

Photo by Matthew Septimus

There are numerous ways to teach media literacy, and Hobbs says many teachers rely on resources like the New York Times Learning Network, which provides grade-appropriate lesson plans for teachers looking to use the day’s paper in their classrooms. Some approaches focus on teaching kids to identify the genre, author, and source of information in order to categorize articles on a continuum from fallacious to credible. Another method, created by librarians at the Association for College and Research Libraries, advises that media literacy (they call it information literacy) focus on six core frameworks, including “Authority Is Constructed and Contextual” and “Information Has Value.”

But the most effective programs, according to Hobbs, take up media literacy not merely as a set of skills—how to spot a fake headline or fact check an article—but as a sensibility that must be taught, nurtured, and practiced. “One of the dispositions teachers complain about is intellectual curiosity,” Hobbs tells me. “Ironically, they have a powerful search engine at their fingertips, but kids have difficulty generating questions.”

At schools without the resources that Ross has—which is to say, nearly every other school—taking a holistic, long-term view of media literacy can be an unaffordable luxury. Access to curricula costs money and time, and public schools are bound by state requirements that private schools have leverage to ignore. Particularly for students living in under-resourced districts in cities or rural areas, there isn’t likely to be a whole lot of room for experimentation and unique elective coursework of the sort students at Ross enjoy.

Still, Hobbs insists that private, moneyed schools are not the only places meaningful media literacy education can happen. She points to the Brooklyn School of Inquiry, a public school in Bensonhurst for gifted elementary and middle school students, which partnered with Rhys Daunic’s The Media Spot to integrate media literacy into the curriculum. Classes led by Amanda Murphy, a social-studies teacher at Rhode Island’s Westerly High, are among the most impressive Hobbs has seen, thanks to Murphy’s integration of media literacy concepts. In Philadelphia, Mighty Writers, an after-school workshop for public-school kids, offers sessions on fake news that make use of tools like Snopes and Checkology, a partnership between the News Literacy Project and the Facebook Journalism Project. Teenagers dissect memes, discuss where they get their news (or don’t) and why, and hear from journalists on how they conduct investigations.

But once kids learn to be skeptical of what they read online, everything can be thrown into question. At a recent workshop in Philadelphia, a clever boy asked the instructor, “How do you monitor Snopes? If they’ve told the truth before, they could slip in a lie without you noticing.”

The pressure on children to question all they see can be overwhelming. The same feelings of burnout and disillusionment that adults have reported while following the news over the past several years have affected kids, too. Especially when it comes to the fake news that fills their phones, the idea that they might not be able to trust is a heavy burden to carry, Gansky explains. “As much as they like to perform being adults, man, you can hit just a couple of pressure points and they go, ‘I don’t like being in the deep end. What do you want me to know?’ ”

Students pick up on the declining faith in major news organizations. “A couple years ago, when I began teaching, calling the New York Times the paper of record raised no eyebrows,” Gansky says. But the polarization of politics—and of news consumption—has changed that. “Now I think students are dealing with a lot of cognitive dissonance where they go, ‘God, everything has to be interrogated; there’s no stable referent here.’ How many betwixt-and-between conversations can they deal with before you have to draw a line in the sand and say this can be empirically proven, and this seems like supposition or speculation? And are there very, very clear ways that we can tell those two apart?”

The types of news media that Ross students consume vary widely, and international students bring a range of perspectives. An assumption of belief in the existence—and necessity—of a free press can’t be taken for granted. “My Chinese students present a really different scenario,” Gansky says of his e-commerce pupils. “They will say, ‘Well, we know that everything is fabricated by our state.’ So my job is to say, hey, there are certain things that we can tell are true, and if you follow these steps in terms of basic research you can start to tease out whether this thing has legs or not. For them, it’s working through their immediate cynicism.”

The most effective programs take up media literacy not as a set of skills—how to spot a fake headline or fact check an article—but as a sensibility that must be taught, nurtured, and practiced.

American students “are usually the worst” at judging the credibility of information found online, Gansky tells me. “They are so confident in their abilities to tell what’s true and what’s not that they often don’t do the basic research. They’ll just trust their emotions.” German students, he adds, tend to be good at spotting where the truth has been stretched.

When all of these backgrounds come together in a classroom, teaching can be complicated. During a lesson on Airbnb and Uber as disruptive technologies, the e-commerce class sifted through news articles, academic reports, and op-eds offering divergent viewpoints on the two companies. The frustration of the class, Gansky recalls, led to “a mutiny.” He explains: “They were saying that the data didn’t stack up and they didn’t know what I want them to get from this. What’s the multiple-choice answer? What do you want from me? You’re my sense of authority.”

He was honest with them. “I share your confusion and I share your fear about what might be true and what isn’t,” Gansky remembers telling the class. “ ‘What you guys are feeling is not just an 11th-grade problem. It’s a problem that adults are having.’ That is kind of refreshing for them.”

Ross has long looked for ways to bring current events into the media curriculum in real time. In the past several years, the tone of the news seems to have become grimmer—sexual assault, mass shootings, war, family separations, racist comments from the White House—and even though Ross students come across as particularly savvy, they are still children. Maciak recalls the sense of despair her class felt after spending several weeks engaged in news media. “Many kids would react by saying, ‘This is incredibly depressing. When are we going to talk about something happy in this class? I just want to shut this off,’ ” she says. When the content of the news is inherently age-inappropriate, how do you bring it into the classroom in a responsible way?

That question was put to the test in late September, as the country geared up for a contentious confirmation hearing: Brett Kavanaugh, the Supreme Court nominee who was credibly accused of sexual assault, was set to appear before the Senate Judiciary Committee to answer questions about allegations made against him by Christine Blasey Ford, a psychology professor from California who knew him when they were teenagers.

The Ross Academic Council—made up of administrators and teachers, including Gansky—met to consider how best to approach the event. Should they round up the students, sit them in the gym in front of a television, and screen the hearing? Gansky says there were concerns about plunging them into the deep end without the necessary context. Did the students, especially those from abroad, sufficiently understand the nuances of the Supreme Court and its history with allegations of sexual abuse? Were they prepared to discuss a woman’s assault with sensitivity and maturity? As for the faculty, could they handle the trauma that such a conversation might evoke in students? “Some felt that 11th and 12th graders could handle it, but middle schoolers had barely gotten to sex education,” Gansky recalls. “Middle school teachers said, ‘We don’t feel comfortable bringing this into the classroom. We haven’t done enough groundwork.’ ”

Gansky had discussed related news stories in his classes. His students had learned of the Harvey Weinstein sexual harassment scandal, and when they arrived at school talking about it, Gansky assigned reading from the Times and The New Yorker to facilitate a class discussion about the allegations. At the time of the Kavanaugh hearing, Gansky says, “I was really hoping to pair up with a history teacher so they’d get some understanding of the judiciary and I could explain how the narrative was instructed by news media.”

“When are we going to talk about something happy in this class?”

The council, which makes recommendations to the head of the school, decided against a mandatory Ross-wide screening of the hearing, advising instead that teachers make case-by-case decisions based on student preparedness and age. The hearing was, of course, a spectacle, lasting eight hours; afterward, Gansky wanted to let his students decide whether they would discuss it in class. The topic was clearly on their minds, but Gansky says the group, perhaps uncomfortable with the subject matter, opted for business as usual.

Still, the lessons they’d been learning helped them process the events of the day—and would stand them in good stead for those yet to come. In November, for instance, Beeton voted for the first time. “If I read something and I don’t think that it’s the full truth, then I’ll ask someone about it, or look it up online, or find a different article about it,” he says. “I think this e-commerce class and the 11th-grade media class helped everyone who took them get to a place where we can critically question or analyze information. Not to a point where we’re constantly distrusting of the news, but we know how to question and we know where to look.”

Alexandria Neason was CJR’s staff writer and Senior Delacorte Fellow. Recently, she became an editor and producer at WNYC’s Radiolab.