On Friday the thirteenth of March, Lourdes Torres, the senior vice president of political coverage at Univision News, traveled from Miami to Washington, DC. Her team was to cohost, along with CNN, the first virtual presidential debate in United States history. Nearly two thousand Americans had already tested positive for the novel coronavirus; more than forty had died. In a matter of days, the debate’s organizers had decided to move the event from a large theater in downtown Phoenix to a television studio in the nation’s capital. There would be no crowd in the room—no raucous cheers or applause, no in-person audience questions. The two Democratic candidates, Joe Biden and Bernie Sanders, would have to stand six feet from each other. The moderators would need to account for the public’s sense of fear and doubt over the spread of covid-19. This was to be a defining event in the election, and a test with no precedent for everyone involved. “I left Miami that day feeling as if a hurricane was coming our way,” Torres said.

Florida was still weeks from a lockdown, but people were beginning to worry about stocking up their pantries and filling up their gas tanks. Having worked at Univision for nearly three decades, Torres soon realized that covid-19 would be the single most disruptive story of her career. Fifty-nine and born in Cuba, with shoulder-length auburn hair and a slight gap between her front teeth, she is a behind-the-camera person, but the decisions she makes on set are always visible. Her staff looks to her for everything from story planning to conflict resolution. “When you’re dealing with an emergency situation such as this one, you’re not thinking about strategizing or about what needs to be done the following month,” Torres said. “You basically go into survival mode.”

The week before the debate, Jorge Ramos, Univision’s biggest star, had to drop out as host—he was worried he’d been exposed to someone with covid-19—and Ilia Calderón, another anchor at the network, took his place. Univision banned all nonessential travel; in order to fly to Washington, Torres had to request a waiver from her supervisor for herself and four others—a small delegation compared to the multitude who awaited them at CNN. When she got in a taxi at Reagan National Airport, she asked her driver how he was coping with the crisis. He replied by saying she was his first customer in four hours. “My mind was set on figuring out how to reflect that kind of hardship during the debate,” Torres told me. “And the conversations we were having with the team were all about translating those experiences into questions for the candidates.”

Once they arrived, Torres and Calderón hunkered down to prepare with their staff. Typically, debate hosts have several weeks or more to familiarize themselves with the material they will be covering. In this case, Calderón, who is forty-eight, had only a few days. Univision’s team compiled research on each candidate’s proposals for healthcare, the economy, immigration, and US foreign policy on Latin America. Long hours were spent at CNN’s office, where Calderón joined Jake Tapper and Dana Bash for mock debates. “Our priority was to bring up Latinos to the table,” Calderón said. She wanted to ensure that the candidates would address the needs of America’s eleven million undocumented workers—many of whom were deemed essential but continued to live in fear of deportation—and of all Latinos who have felt targeted by President Trump’s derision. She wanted to remind everyone in the room that Latinos could be pivotal to the 2020 election.

By the time the event was held, that Sunday night, Biden and Sanders were moving their campaigns entirely to digital. El debate demócrata began with the two men walking into an empty CNN studio and exchanging an awkward elbow bump. “Welcome to this unique event,” Tapper said. The three hosts sat straight backed, their hands resting on a high acrylic table. When Tapper introduced Calderón, who wore a V-necked pink dress, her eyes darted left and right; she flashed a bashful smile.

Calderón asked Biden and Sanders to explain how they would handle the economic ravages of the pandemic—a matter of urgent concern for the 84 percent of Latinos who are unable to work from home. The median household income of Hispanics is three-quarters that of whites; after Native Americans, they are the most likely of any group in the country to lack health insurance. Calderón pressed the candidates to speak about comprehensive immigration reform, deportation raids, and sanctuary cities. Each man offered a pitch to Latino viewers. “Look, we are a nation of immigrants—our future rests upon the Latino community being fully integrated,” Biden said. “Twenty-four of every one hundred children in school today, from kindergarten through high school, is a Latino. Right now. Today. The idea that any American thinks it doesn’t pay for us to significantly invest in their future is absolutely a bizarre notion.”

In hindsight, Torres wishes the debate had been held a month later. By then, statistics made it evident that the virus disproportionately affected Latinos, who, because of their low incomes and immigration statuses, were all the more vulnerable. Within weeks, news surfaced of workers dying at meat-processing plants; millions of business owners grappling with bankruptcy; and many more losing their jobs. “The coronavirus has exposed the cracks in society,” Torres said. “These cracks are never the focus of debates—they’re certainly not discussed as bluntly and openly as they are now.” Torres had wanted the debate to reveal that the political interests of Latinos are inextricably linked to those of the entire American population. The question afterward, as the campaigns became overshadowed by the coronavirus, was how Univision could keep Latinos in focus.

She wanted to remind everyone in the room that Latinos could be pivotal to the 2020 election.

“People depend on us,” Ramos, who is sixty-two, told me recently from his office, in Miami. “Univision is a lifeline to survive in the United States, and our audiences expect us to do much more than just deliver the news.” The notion of a television network being a lifeline may seem an exaggeration, but in polls, Latinos have consistently ranked Univision as one of the most trusted institutions in the United States, second only to the Catholic Church. Its coverage, entirely in Spanish, reaches the homes of people who speak it as a first language. During its prime-time news hours, Univision has an audience of nearly two million.

Univision grew from the first Hispanic TV channel in the US, which went live in San Antonio in the summer of 1955. In the early sixties, a group of businessmen, including Emilio Azcárraga Vidaurreta, a Mexican communications tycoon, bought the channel and some others to create the Spanish International Network, now known as Univision. Among the group’s purchases was KMEX-TV, a station based in Los Angeles, where Ramos—freshly arrived from Mexico City—began working as a reporter in the mid-eighties. KMEX, he realized, was not a typical newsroom. It hosted health and employment fairs for its audiences and offered advice on the best schools for Hispanic youth. The mission was not only to inform, but also to empower and serve Latinos—

a mandate that Univision eventually made its own.

Since then, the Hispanic community in the United States has quadrupled in size, comprising some sixty million people. This year, for the first time, Latinos are the country’s largest minority voting group. Many of them see Ramos and his colleagues as the best large-scale advocates they have, and Univision as their main access point to politics. “There is an absolute leadership vacuum at the national level,” Torres told me. When Julián Castro dropped out of the 2020 presidential race, in January, he delivered a blunt message: “It simply isn’t our time.” Congress now has the largest class of Latinos in history—totaling thirty-eight—but there are only four Latino members of the Senate. Ramos, the elder statesman of the Latino media elite, outranks them all.

Over the decades, if it’s been covered at all, the Latino demographic has typically been cast in the press as a “sleeping giant”—a term meant to evoke its tremendous, yet dormant, potential. “For a long time, everyone expected the sleeping giant to wake up, without anyone setting the alarm,” Stephanie Valencia, a cofounder of a research group called Equis Labs, told me. Many Latinos felt disengaged from the political process because no one was speaking directly to them. News outlets repeated the failures of candidates, who for decades saw the Latino electorate as a monolith. It didn’t matter whether politicians or journalists were addressing Mexicans, Central Americans, Puerto Ricans, or Dominicans—their message remained the same. And, for the most part, it centered on immigration. As a corollary, Latino turnout has lagged compared to that of other voting groups. In 2008, the last time the country saw an economic crisis comparable to today’s, participation rates among Latinos were dismal. In 2016, less than half of eligible Latino voters cast their ballots.

Only recently have campaign strategists begun to tap into Latino voters’ yearning to be part of the political process. And Univision has been uniquely positioned to cover the community’s political rise. During the 2016 election cycle, Ramos made headlines for being ousted from a press conference at which he grilled Trump about the wall and deportations. Ramos has been similarly tough on Democrats. “Would you take responsibility for the three million people that were deported during the Obama-Biden administration?” he asked Biden in February. “Many people are expecting you to apologize for that—to say that it was wrong.”

“I think it was a big mistake,” Biden responded. “It took too long to get it right.”

Biden, for lack of money or will, largely failed to engage with Latinos in the primaries. He lost to Sanders among these voters in all states with a sizable Hispanic population except Florida. Now that Biden is the presumptive Democratic nominee, it’s unclear whether his campaign can win over the demographic in time for November. Laura Jiménez, Biden’s Latino-engagement director, told me recently that it was crucial for the campaign to “meet people where they are,” but she wouldn’t offer any specifics on the budget allocated for doing so, the plan she would follow, or even the lessons she had learned from the primaries. Events continue to be online only.

Univision sees its responsibility to educate Latino voters—to be “the bridge between candidates and voters,” as Ramos told me. But ultimately, a news channel—no matter how much trust it has earned from its audience—cannot compensate for the work of campaigns. “You can give people the information they need to go out and vote, but they will need to have an incentive to do so,” Torres said. “That is where politicians have to come in and take Latinos seriously. Latinos will listen. They will know who is doing the work that needs to be done—and who isn’t.”

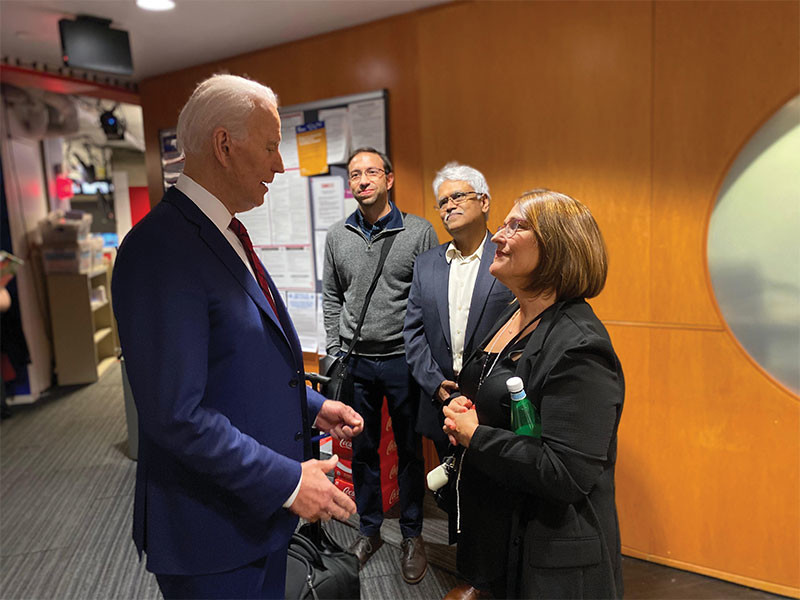

Behind the Scenes Lourdes Torres speaks with Joe Biden pre-quarantine. Univision News.

Like many other outlets, Univision had to frantically adapt its coverage to the fast-evolving nature of the pandemic. Although the network started reporting on the coronavirus from the time it surfaced, in Wuhan, China, anchors weren’t prepared to grant it their full attention until the crisis overwhelmed the United States.

Enrique Acevedo, forty-two and the anchor of Univision’s nightly news show, was the first among the staff to ring the alarm. Early this year, he’d attended the World Economic Forum, where he met Chinese leaders, including Hong Kong’s chief executive, who warned him and others of the imminent risk of covid-19. Acevedo had covered the 2009 H1N1 pandemic in Mexico, where he’d witnessed the deadly effects of swine flu. The dispatches from his Chinese colleagues sounded frighteningly familiar. “I came back from Davos in mid-January and told my team that we needed to be speaking much more about the topic,” he said. “I remember their response being, ‘But why? We already put out two stories last week!’ ” He kept insisting. In early February, he reached out to Daniel Coronell, Univision News’s president, urging him to allocate resources to the network’s covid-19 response, including gear to protect employees. Acevedo asked about a contingency plan, in case the staff became infected. What would happen if the anchors fell ill? Where would they record daily news shows? His alarm went unheeded.

Then March rolled around. The number of covid-19 cases in the US rose significantly; many of Acevedo’s colleagues realized that the pandemic wasn’t as distant as they had thought. “One week we had a normal news show focused on politics, the economy, immigration, and all the other topics,” Calderón said. “And all of a sudden, we were plunged in a show where all that mattered was to inform people about what was happening around the coronavirus.” Most staffers in Univision’s news department were sent home. Only those deemed essential—roughly 10 percent of all five hundred employees—were required to work from the studio, in Miami. Among them were engineers, sound technicians, and camera operators, whose labor was needed to keep the control room running. Everyone entering the studio was required to fill out a medical questionnaire before setting foot inside. A cleaning crew was on call; phones were sanitized constantly. All meetings, including twice-daily editorial check-ins, took place over the phone, and became subject to awkward silences, frozen images, and cumbersome exchanges.

In late March, two employees tested positive for covid-19. Univision temporarily closed its studio, and the evening news team had to record from a parking lot. Under a blazing sun, production hands set up folding tables, teleprompters, light stands, and cameras to film the program outside. The building was later sanitized, and no additional cases surfaced, but Univision continued taking precautions. Any journalists still leaving the house to cover the pandemic were required to wear N95 masks and gloves; they also carried long sticks for their microphones and kept a safe distance from people they interviewed. Those reporting from home set up makeshift studios, with the occasional intrusion of a child or pet. From one day to the next, on-air personalities turned into amateur makeup artists and hairstylists. The audience seemed to enjoy peeking into the homes of their favorite anchors, but producers had to cope with not being able to fix the lighting and frame the shots as they once did. “We have little control over the quality of our productions,” Torres said.

By then, Univision had realized that its viewers were seeking even more information about the pandemic. Coronell and María Antonieta Collins, another veteran Univision anchor, decided to put together a new show in the 3pm slot—The Coronavirus Diary—which would be cohosted by Ramos and aired live on Univision and on Facebook. When the show started, Ramos was still in quarantine, so he joined the broadcast via Skype while Collins took the lead from the studio. Dr. Juan Rivera, Univision’s chief medical correspondent, called in to answer questions from the audience: Is it safe to treat covid-19 symptoms with ibuprofen? Why is hydroxychloroquine in short supply? Does remdesivir really work? The program delved into practical concerns, including when to expect stimulus checks and whether undocumented workers qualified for federal aid. Ramos and Collins also showcased stories of Latinos on the front lines—a Puerto Rican nurse spoke about conditions at the intensive-care unit of her hospital, in the Bronx; Collins wore a face shield made by a Colombian businessman who had repurposed his printing company. The Coronavirus Diary reached as many as 15.9 million viewers. Soon, Ramos returned to the studio, and the two anchors began presenting the news sitting six feet apart.

The show’s second episode coincided with the March 17 Democratic primaries, which took place in Florida, Arizona, and Illinois. President Trump had just released his “Fifteen days to slow the spread” guidelines, and recommended avoiding gatherings of more than ten people, yet only Ohio decided to alter its original plans. Univision needed to find a way to cover the health story alongside the election news. A correspondent in Chicago said that, at the polling station where she was, only half the people who would typically have cast their ballots showed up. In Florida, Univision reported that election authorities expected just 20 percent of registered voters in Miami-Dade County—where a large majority of residents are Latino—to appear at the polls. That prediction had been made before covid-19 upended everything; now Latino turnout in Miami-Dade looked even bleaker. Ramos was troubled. “I hope that Latinos won’t make the same mistake they did in 2016,” he told me. “We just don’t know how the pandemic will affect voter participation.”

During the pandemic, Univision’s ratings have skyrocketed. But to keep the numbers high, its leaders will need to strike the right balance between a crisis with no foreseeable end and an election scheduled for the fall. “No topic can be dissociated from the pandemic at the moment,” Torres told me. “That applies to any topic you may be covering—including politics.” Daniel Morcate, Univision’s chief newsroom editor, agreed, but he wasn’t sure how political stories would play with viewers. He felt an obligation to cover the campaigns, yet he knew that Latinos were relying on Univision to help them survive the coming months. “I worry about what we can do to keep the topic of the election alive, given how important it is for the country, and for Hispanics in particular,” he told me. “I think that is our biggest challenge.”

In mid-May, Torres sat on the balcony of her apartment in Doral, just inland of Miami, and waited for her colleagues to join her via Webex. She was hosting a virtual meeting with Univision’s art department to review the motion graphics they will use on election night. Rosa Mosqueira, the only person calling from the studio, was in the control room; her role was to pull up the options and move the camera around to see the set from different angles.

The designers had been working on the graphics for more than two months. Mosqueira showed the group an image of Trump taking 57.5 percent of the vote in North Carolina, Biden 42.5 percent. It was adorned with blue stripes and “2020” in the background. A debate ensued. “I don’t know if I like the stripes clumped up,” an art director said. “Maybe some of those blue lines should be dimmed down a little.” Someone spoke over him, in disagreement. They went in circles, voices crossing helplessly in the video chat. Torres cut in, asking for someone in the studio to stand onstage, so they could all see how the graphic looked. “Maybe the final solution is a combination of both ideas? I don’t know,” Mosqueira said.

After everyone had their say, Torres ruled, asking for one more revision. “It’s like a puzzle,” she told me after the call. Normally, they would all have been together in the control room; it would have been easier to make changes on the spot. The only upside of working remotely was that everyone was seeing the set from a small screen, as their audiences do. Still, Torres was hoping to delay her return to the office as much as possible. She recently recovered from gastrointestinal cancer, she explained, and her doctors had advised her to stay home as long as she could.

Until things got back to normal, she needed to figure out how to reintegrate campaign news into Univision’s coverage. In conversations with senior producers and representatives of the network’s local stations, not everyone agreed. “We all share a sense of responsibility over keeping our viewers informed on the coronavirus, but that also applies to other topics,” Torres said. “There are those who think we should continue to focus on the pandemic; others, like myself, believe it’s important to cover more political news.”

The responsibility to which Torres alluded came with a high level of scrutiny. After George Floyd, a Black man in Minneapolis, was killed under the knee of a white officer, Univision (and its competitor, Telemundo) were accused of dedicating too much airtime to the looting and property damage that emerged from protests across the country; instead, critics said, the focus should have been on police brutality. “Hispanic media like Univision & Telemundo are so selective on whats broadcasted in regards to the protests and riots going on knowing thats where the majority of our latin/hispanic parents depend on 4 info,” a viewer wrote on Twitter. Some argued that Univision was falling into racial prejudices against Black people that pervade the Latino community. They called for broader representation of Afro-Latinos in the newsroom and held Hispanic outlets accountable for their power to sway public opinion. The controversy, which was largely stirred by young voices, made it clear that Univision had yet to figure out how to engage those viewers—many of whom get their news online and have a preference for English. “Our audiences are much more fractured now and shared with many more outlets,” Torres told me. Univision had spent heavily on its website and on its social media presence; the importance of that demographic was understood, at least. “Young Latinos are the lifeblood of our community,” she said. “These are the ones that will help their parents exercise their right to vote.”

In the immediate term, Univision was aiming to bring together voters and candidates through virtual town halls. In May, Torres joined the League of United Latin American Citizens (lulac) in arranging a conversation with Biden, members of Congress, activists, and the sons and daughters of Latino workers at meat plants. The event, held on Zoom and moderated by Acevedo, focused on how to protect essential workers. “They designate them as essential workers, then treat them as disposable,” Biden said. Domingo García, the national president of lulac, reminded the audience that five thousand workers at meat plants had tested positive for covid-19 and twenty had died; until a few weeks before the town hall, employees were handling food without face masks. Relatives of these workers said that many in their families had caught the disease; they were determined to speak up on their behalf. Each panelist addressed the imperative to protect workers in the short term, to ensure that none lacked necessary protective gear, that none would be deported. As for the long term, some argued, the fate of essential workers would be determined on Election Day, and only Biden could upend the status quo. But he had yet to successfully make that case for himself, Torres observed. “A lot will depend on what Biden does, on whether he prioritizes engaging with Latinos,” she told me. (In June, Acevedo left Univision.)

Torres is still grappling with how to cover Trump. Univision initially aired his coronavirus briefings live but later decided to simply have anchors report on them. “It’s a very difficult predicament,” Torres said, “because we need to be constantly balancing people’s right to have full access to these briefings while also being mindful of what other outlets are doing.” Reporting on Republican candidates had grown increasingly difficult since 2012, when the party’s position on immigration hardened, Torres explained. “They didn’t want to answer our questions, because they knew we would get right at the topic.” In 2016, she said, Trump only exacerbated the problem. “It became toxic for candidates to be associated with Latinos.” Three months ago, she reached out to the White House, asking for a prerecorded clip of the president to include in a special episode on the coronavirus. She has yet to hear back.

“There are too many unknowns about the election for us to know exactly how we’ll cover it,” Torres said. “But our sense of mission has become all the stronger because we are one of the few resources a lot of people in our community have. And they can trust we’ll be there for them every day.” In the coming months, Torres will have to determine how to cover primaries that have been postponed and whether party conventions have become obsolete. She’ll come out of her seventh presidential election with Univision having learned how a political contest unfolds in the midst of a pandemic. She hopes that she will have elevated the profile of Latinos in the eyes of the campaigns. The stakes are higher than ever. Thirty-two million Latinos are eligible to vote this year. If they show up, their influence could be decisive.

Stephania Taladrid is a contributing writer at The New Yorker. Before that, she served as a speechwriter for the Obama administration. She holds a master’s in Latin American studies from the Edmund A. Walsh School of Foreign Service at Georgetown University.