Yes, as Kira Goldenberg writes, the most remarkable finding of the big new Pew study on nonprofit news organizations is their confidence in their own future—fully 81 percent said they were “very” or “somewhat” confident they’d be solvent in five years.

That’s heartening.

But, as Pew itself hints, it’s hard to know exactly what that confidence is based on, and whether we, the rest of us, can have any confidence that these operations will ever become more than they are now—marginal supplements to a deracinated news-gathering infrastructure.

First, the good news: Well, first, we have a good number for the universe of nonprofit news organizations, and that number is 172. Pew does its usual rigorous job in scouring the landscape for the category. What’s more, the number is up 25 percent since 2010-2012 and up 46 percent since newspapers began their revenue free fall in 2007-2008. All but nine states have one of these organizations.

And for the most part, they’re doing core reporting. Of the 93 organizations that responded to Pew: 26 percent do general news, 21 percent do investigations, 17 percent cover government, etc.

But as the report makes clear, we’re looking at mostly tiny operations: 52 percent have between 1 and 5 fulltime staffers; 26 percent have none at all. Only 6 percent have more than 25. And that includes business-side people, administrators etc.

By comparison, Pew reports, the 1,396 daily print newspapers in the U.S. averaged 29 full time journalists, and that’s down from 39 full timers in 2001, back in the day.

This isn’t to look at the glass as half empty (though it sort of is that, too) but it is point up the difference between artisanal and industrial scale journalism, even in its current sad state.

And the comparisons become even more striking when you consider actual output of content:

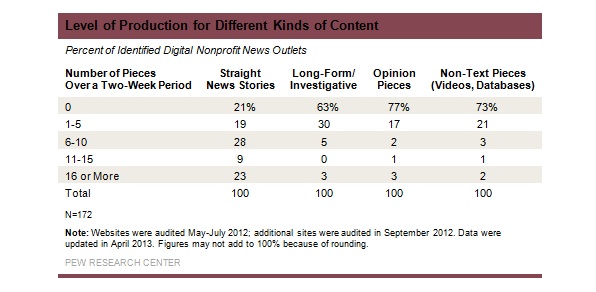

Pew gives this chart that shows nonprofits’ output over two weeks. It shows that only 32 percent were able to post more than 11 straight news stories in the period, that is to say, or more or less put up something everyday. That’s not a knock. But there’s only so much small operations can do, and it speaks to the difficulty of coming up with bespoke content, day in and day out.

Pew doesn’t give totals—and quantity doesn’t matter so much in and of itself, anyway, of course—but extrapolating a bit from the data, you’ll see that all of the nonprofits in the country don’t produce more than what a couple of regional dailies did a decade ago.

To get there, assume that all the outlets in Pew’s study produce at the top of the range in the above graphic (i.e., if you assume “1-5” means 5 stories in two weeks). Then we substitute some higher number for the highest end of the range, since Pew says “16 or more.” Let’s say the top of the range is 25, which is just a guess, but a generous one. So for example, I’ll say 23 percent produced 25 straight news stories, instead of “16 or more.” THEN you double your totals, since only 54 percent of the nonprofits responded.

What you get is about 3,200 stories (3,262 to be exact if you’re figuring along) and 460 stories over 1,000 words every two weeks. (The 1,000-word definition stretches the definition of “longform”—or shrinks it, if you will— but let’s go with it.)

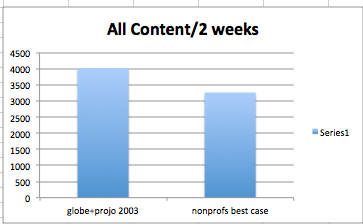

And to be clear: this is beyond generous. But as a point of reference, that’s about less than what two of the national papers did last year (the NYT did about 2500 in two weeks and the LA Times a little more).

Even if the nonprofits’ output is only half that number I posit, which is likely, it is nothing sneeze at.

Still, it’s less than the Boston Globe and Providence Journal did alone a decade ago:

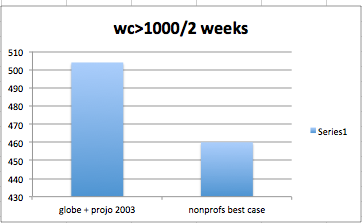

And here’s a graph for stories longer than 1,000 words:

Actually, the Globe alone did more than nonprofits’ best-case scenario but the point is made. Again, not to look a gift horse in the mouth. It goes without saying that this production is much better than the alternative—which is nothing.

But it also helps to show that, even if you weren’t a fan of old media, how big a hole there is to fill, at least in term of quantity and, it’s fair to say, sheer coverage.

Which brings us back to the confidence question. Nonprofits got their revenue from two main sources, Pew found: Foundations and wealthy individuals.

“Other forms of income,” Pew says, “pale by comparison.” Sponsorships, ads, events, and other income sources were still supplemental at best:

Nearly half of the organizations with at least three streams generated 75% or more of their revenue from just one of those–almost always foundation grants.

Foundations and wealthy individuals are important revenue sources, and will continue to be, one hopes, for a long time. But philanthropy goes up, and it comes down. It is many things, comes in many forms, and has been described in many ways. But it cannot be fairly described as a model for growth.

And, as respondents reported, one of their biggest needs is the time to raise money and create a business model:

When one small nonprofit news organization discussed its ongoing struggle to raise money, the message was simple. “We don’t have time to do this,” it reported. “And we don’t know how.”

Fair enough. That’s not uncommon in nonprofit news, and we’re not strangers to the problem here.

But the question at this point is, nonprofits’ confidence notwithstanding, where does the growth come from?

Dean Starkman Dean Starkman runs The Audit, CJR’s business section, and is the author of The Watchdog That Didn’t Bark: The Financial Crisis and the Disappearance of Investigative Journalism (Columbia University Press, January 2014). Follow Dean on Twitter: @deanstarkman.