Sign up for The Media Today, CJR’s daily newsletter.

Clay Shirky, a leading paywall skeptic, deserves credit for grappling with what is now generally conceded to be the clear success of The New York Times‘s digital pay model.

Shirky makes the counterintuitive argument that NYT’s success, coupled with the supposed failure of the Times of London own paywall, “are a blow to the idea that online news can be treated as a simple product for sale, as the physical newspaper was.”, He argues that the failure of the London paper’s rigid paywall (no free stories; readers have to pay to see anything) shows that selling online news is not a “simple product” transaction.

Further, he argues that even a successful leaky paywall (readers get to see some stories but pay for unlimited access) will push newspapers like the NYT to focus on the niche interests of its subscribers at the expense of its mass readership.

He makes some interesting points, once they are translated, but what stands out immediately is that a leading future of news (FON) thinker, faced with evidence contradicting a cornerstone of the theory—that people won’t pay for news online—is still working to show that even when people are paying for news online they aren’t, well, you know.

Can we agree, at least theoretically, that when people do pay for news online, that that would be a good thing? It’s okay to disagree, but it seems to me the FON side of the debate needs to clarify its position on the matter: Is charging for journalism merely impractical or is it wholly undesirable?

Starting with the Times of London’s paywall, Shirky presents it as a flat failure and proof that online news payments are not “simple product” transactions.

One early sign of this shift was the 2010 launch of paywalls for the London Times and Sunday Times. These involved no new strategy; however, the newspaper world was finally willing to regard them as real test of whether general-interest papers could induce a critical mass of readers to pay. (Nope.)

Much as I think the Times of London went wrong installing a rigid paywall rather than a leaky one, to judge its merits fairly we need to look at better data than Shirky gives us via a speculative story written a year and a half ago, three weeks after the paper put up its paywall. That story reported that the Times‘s web visitors plummeted 90 percent after the paywall and guessed that it had just 15,000 online subscribers.

More recent reports have said that Times traffic in the UK, the audience most of its advertisers want to reach, was actually down 42 percent (lots of people still visit the home page, apparently). And in October, News Corp. said that the Times of London now has more than 111,000 paying digital subscribers, up 41 percent in six months. I might not call that “critical mass,” and we don’t have ad numbers, but it’s nothing to scoff at for a paper with the daily print circulation of The Arizona Republic.

While the Times of London case is more nuanced than Shirky would have us believe, I’ll leave it to readers to decide whether even a total failure would show that buying news online is not a simple transaction.

Now anti-paywallists are presented with a harder case, a bigger “problem,” if you will: The New York Times.

Here, Shirky argues that readers in that case are paying $16 a month not because they necessarily want or need journalism, but because they want to support the journalistic cause:

When a paper abandons the standard paywall strategy, it gives up on selling news as a simple transaction. Instead, it must also appeal to its readers’ non-financial and non-transactional motivations: loyalty, gratitude, dedication to the mission, a sense of identification with the paper, an urge to preserve it as an institution rather than a business.

Shirky argues that, like donors contributing to NPR, New York Times subscribers pay $16 a month out of a sense of civic obligation (“support the cause”) rather than as an exchange of value (“you’ve got what I want and I’ll pay you for it.”)

I’m sure lots of subscribers want to support the paper, but some evidence would be nice. Isn’t is just as likely that the paper’s digital subscribers pay for the NYT because they like to and/or need to read it, and because the NYT now charges them to do so? Indeed, the NPR analogy really isn’t apt. In the public radio case, people pay when they don’t even have to. In the newspaper case, they pay only when compelled to. In this case, it takes a wall.

All in all, it’s not clear how a successful paywall at the NYT (and, apparently, at the Star-Tribune), and a less-successful one in London show how leaky paywall purchases aren’t simple transactions.

This logical leap is related to an oft-asserted and seldom backed-up tenet of future-of-news thought is that readers have, actually, never paid for content, which shows up in this quote from Shirky’s piece:

In fact, as Paul Graham has pointed out, “Consumers never really were paying for content, and publishers weren’t really selling it either…Almost every form of publishing has been organized as if the medium was what they were selling, and the content was irrelevant.”

Again, evidence would be nice here, but none is offered. Is the content of the New Yorker really irrelevant to people’s decisions to pay for it? How about The Wall Street Journal after it revamped its journalism in the 1940s and grew circulation by a factor of 50?

Is it really possible to separate the medium from the content, and what would be the point?

This assertion (consumers have never “really” paid for content) is a doubling-down on the FON view that journalism has little intrinsic worth (see John Paton: the value is ”about zero”, a view that is at best debatable and, coming from journalism academics and news people, strange.

How many digital subscriptions need to be sold before FON thinkers conclude that journalism may, in fact, have some economic value and that, potentially, the greater the quality, the higher the value?

The truth is, readers have been paying for both the medium and journalism content for years. The trick is, it has to be of high quality.

To show how few people will really pay for news and that paywalls will leave newspapers with only niche customers, Shirky makes the the true observation that only a fraction of online readers actually subscribe.

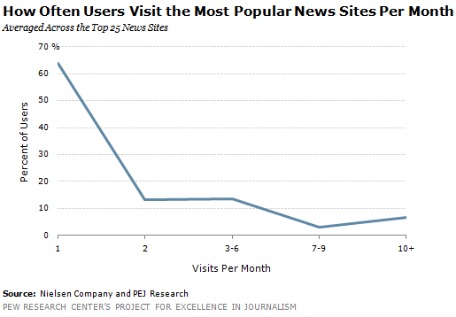

Calling article thresholds a “leaky” or “porous” paywall understates the enormity of the change; the metaphor of a leak suggests a mostly intact container that lets out a minority of its contents, but a paper that shares even two pages a month frees a majority of users from any fee at all. By the time the threshold is at 20 pages (a number fast becoming customary) a paper has given up on even trying to charge between 85% and 95% of its readers, and it will only convince a minority of that minority to pay.

(Note as an aside: Shirky here says the Times‘s leaky wall is really a wall; earlier to make the NPR case, he said the leaky paywall was a retreat from a paywall: “When a paper abandons the standard paywall strategy, it gives up on selling news as a simple transaction….”)

In any case, Shirky’s analysis puts far too much significance on what are mostly new, casual online readers, who are neither customers nor even potential customers, and don’t need to be. Dare I call this the junk traffic ? Most of the unique visitors a newspaper site gets are noise, drive-by traffic they get from Reddit or Drudge that’s worth almost nothing besides marketing. It’s like counting people who walk by the newsstand and glance at the headlines but don’t ever buy the paper.

About 14 percent of NYT readers online account for 75 percent of its pageviews, so it’s just not helpful to think of the vast majority of online readers as potential customers. In reality, if you read just one or five pages, you’re almost certainly not going to pay. But if you read more than twenty NYT articles a month, you have to pay, unless you’re willing to cheat the system (and while many people, unfortunately, are, even more aren’t or don’t bother). And this idea ignores the fact that hundreds of thousands of people are already paying for news and magazine subscriptions via iPad apps and e-readers. Are those people going the NPR route or are they paying for digital news because they have to in order to read their favorite publications on their gadgets?

While The New York Times has made it for decades with about a million print subscribers, it now has roughly thirty million online readers in a given month. But absent a paywall, most of those online readers are essentially worth nothing to the paper, visiting it only a few times a year. It’s not going to turn these folks away, but it shouldn’t focus much (if any) effort on them. They’ll continue to come as long as the NYT serves its core readers, which is not some new paywall phenomenon, but something that it’s been doing all along. The paper has calculated, correctly, that it can keep the ad revenue while adding tens of millions of dollars from subscriptions. Traffic (unique visitors) is actually up 2 percent at nytimes.com since the meter went up and it took in 6 percent more in digital advertising in the third quarter than it did a year ago without a meter.

Shirky says the new paying online subscribers are a niche, “almost certain to be more political, and more partisan, than the median reader.” But, again, there’s no evidence presented to support that. How exactly are paying digital subscribers different than paying print subscribers, who also choose “sports” or “politics” or “food.”? Come to think of it, if people are paying for unlimited access to the whole newspaper, just like before, is bundling really dead?

In any case, Shirky calls these digital subscribers a “niche,” but six months after launching, the NYT‘s paid digital circulation (424,000) is already nearly half its paid daily print circulation. Take out the 100,000 subs paid for by a sponsor, and it’s still more than a third. The Wall Street Journal has more than half a million digital-only subscribers and another half a million-plus who pay for it on top of their print subscriptions. If these are niches, they’re awfully big ones. It’s unclear why a million-circ newspaper is “mass-mass” while a 400,000-circ digital edition isn’t.

Paywalls are hardly a panacea for every third rate paper in the country that disinvested in journalism. But the success of the Times’s metered model shows that people value good journalism and will pay for it when charged.

Maybe it’s not so complicated after all.

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.