Sign up for the daily CJR newsletter.

Ian Urbina’s magisterial probe in The New York Times of OSHA’s failure to police long-term health risks—like harmful fumes caused by glue used in furniture plants—is without doubt a great example of agenda-setting public-interest reporting of a kind that, sad to say, is becoming increasingly scarce among mainstream business news outlets.

The 5,400 word piece—yet another example of the indispensability of longform newspaper writing that itself is becoming an endangered species—explores how and why the furniture industry increasingly uses a chemical known as nPB despite warnings about its consequences for workers from no less an authority than the chemical companies that used to manufacturer it.

The story is smart to point out that OSHA devotes most of its resources to headline-grabbing accidents when toxic workplace air incapacitates 200,000 workers a year and, as the story explains, more than 40,000 Americans a year die prematurely from exposure to toxic substances at work—10 times as many as those who die from refinery explosions, mine collapses, and other accidents.

A few things about the story stand out:

1. The target. OSHA is part of the shadow Washington, the permanent government of regulatory agencies that are vastly under-covered given their importance, the abundance of stories to be found among them, and the number of journalists working in the capital. If only a small fraction of the 15,000 journalists who covered the Republic convention, for instance, could be diverted to the agencies, the news would be vastly more interesting, not to mention useful. The Times, to paraphrase, Willie Keeler, is going where they ain’t, and to great effect.

2. The people. The anecdotes are understated and all the more compelling, and heartbreaking, for that. We’re told, for instance, that Sheri Farley, a 45-year-old worker stricken with “dead foot” from nerve damage, can’t stand the vibration that her kids make playing in the trailer where they live. One of the poorly understood attributes of great journalism is that it can connect segments of society that normally have nothing to do with each other, in this case, the Times elite audience with the working poor of North Carolina. The story reminded me of of how infrequently I read quotes from someone who doesn’t have a college degree.

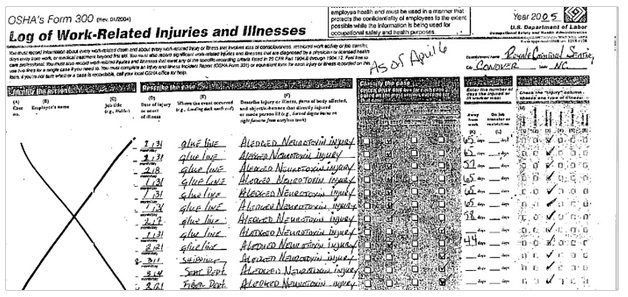

3. The documents. Here’s where interactivity really strengthens a story. This OSHA-required log of work-related injuries shows a long list of incidences of “alleged neurological injury” that the company itself had to record over and over.

And so on.

The flaw in the story is its framing. In a long story like this, it’s necessary to explain what it’s all about, usually with a phrase that begins, “This story shows …”

The Times here has a four-barreled explanation of what the story is about, and it ends up protesting way too much. I’ll add emphasis:

Such hazards demonstrate the difficulty, despite decades of effort, of ensuring that Americans can breathe clean air on the job. Even as worker after worker fell ill, records from the Occupational Safety and Health Administration show that managers at Royale Comfort Seating, where Ms. Farley was employed, repeatedly exposed gluers to nPB levels that exceeded levels federal officials considered safe, failed to provide respirators and turned off fans meant to vent fumes.

But the story of the rise of nPB and the decline of Ms. Farley’s health is much more than the tale of one company, or another chapter in the national debate over the need for more, or fewer, government regulations. Instead, it is a parable about the law of unintended consequences.

It shows how an Environmental Protection Agency program meant to prevent the use of harmful chemicals fostered the proliferation of one, and how a hard-fought victory by OSHA in controlling one source of deadly fumes led workers to be exposed to something worse — a phenomenon familiar enough to be lamented in government parlance as “regrettable substitution.”

It demonstrates how businesses at once both suffer from and exploit the fitful and disjointed way that the government tries to protect workers, and why occupational illnesses have proved so hard to prevent.

And it highlights a startling fact: OSHA, the watchdog agency that many Americans love to hate and industry often faults as overzealous, has largely ignored long-term threats. Partly out of pragmatism, the agency created by President Richard M. Nixon to give greater attention to health issues has largely done the opposite.

Actually, no. This story—like so many others—is about a company using demonstrably dangerous practices for costs reasons, and a compromised regulatory regime. Period. Full stop.

The story itself makes the point here:

OSHA has never set a standard establishing safety limits on workers’ exposure to nPB. The E.P.A. recommended such a limit and considered banning the nPB glues, but it has yet to finalize the plan. It determined that most cushion companies using the glue had fewer than 100 employees, which meant they were less able to absorb the cost of another regulation.

“There just wasn’t the political will,” an E.P.A. official who was part of the decision-making said on the condition of anonymity.

That’s the bottom line.

The Times betrays a strange ambivalence about calling out business malpractice and regulatory failure when it calls OSHA an agency that “many American love to hate”—since when and where’s the evidence?

The Times here—for whatever reason—soft-pedals a straightforward exposé by cloaking it in some gauzy idea of unintended consequences. And there’s no need for it.

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.