Sign up for the daily CJR newsletter.

On Sunday, Zach Dorfman, Sean D. Naylor, and Michael Isikoff reported in an explosive, seven thousand-word story for Yahoo News that in 2017, Donald Trump’s CIA—then under the directorship of Mike Pompeo, a future secretary of state—plotted to kidnap Julian Assange, the founder of WikiLeaks, from Ecuador’s embassy in London, where he was then holed up, and that high-level Trump administration officials even discussed assassinating Assange and asked for “options” as to how to do it. There’s no indication that such plans were ever formally approved, and it’s unclear exactly how serious the assassination talk was, but a number of senior officials were so worried that they privately shared concerns with Congressional oversight panels. The story contends, in perhaps its most attention-grabbing claim, that—after US intelligence agencies began to suspect Russia of a plan to spirit Assange to Moscow and harbor him there—they prepared a range of possible responses, including “potential gun battles with Kremlin operatives on the streets of London, crashing a car into a Russian diplomatic vehicle transporting Assange and then grabbing him, and shooting out the tires of a Russian plane.”

Dorfman, Naylor, and Isikoff describe the frenzied CIA campaign against Assange and WikiLeaks as a response to the latter group’s publication of details concerning top-secret CIA hacking tools, a document drop known as “Vault 7”—Pompeo and top colleagues were reportedly “embarrassed” about the disclosures and, in the words of one former national-security official, “saw blood.” In April 2017, Pompeo publicly described WikiLeaks as a “non-state hostile intelligence service”; at the time, Isikoff (and others) viewed the remark as “a grabby talking point,” but a former official said that the phrase was “chosen advisedly,” and gave the administration a pretext to treat WikiLeaks as it would a state adversary, without jumping through legal hoops or informing Congressional leaders. Nor was Assange the sole target of this effort: under the rubric of “offensive counterintelligence,” American spooks reportedly surveilled other WikiLeaks associates and stole their electronic devices, while working to seed disharmony between them. According to Yahoo, CIA officials entertained the possibility of killing people who weren’t Assange but also had access to the Vault 7 cache.

From the magazine: All of It Matters

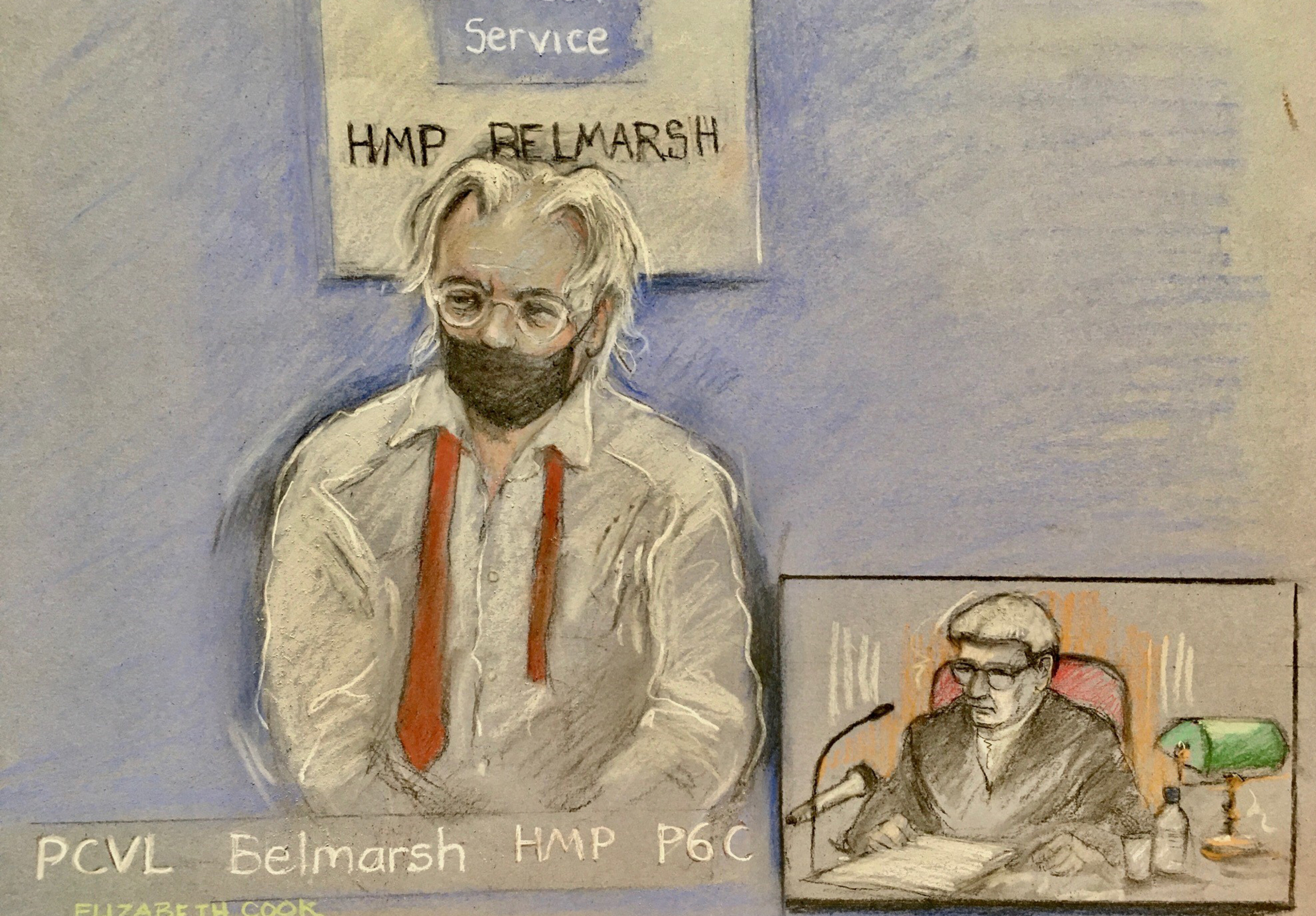

The Yahoo story is directly tied to the US government’s ongoing efforts to extradite Assange from the UK—where he is now in jail, having finally been kicked out of the embassy in 2019—and prosecute him for his work with WikiLeaks; as Dorfman put it on Twitter, “Trump administration officials were both worried about the legality of rendering Assange generally, and particularly concerned about kidnapping him absent an indictment,” and so reportedly accelerated the drafting of charges against Assange so as to have something ready should he be brought onto US soil. Soon after British police dragged Assange from the embassy, US authorities indicted him only for computer fraud, which briefly assuaged the fears of press-freedom advocates who feared that the charges might criminalize the publication of secrets. Those fears were soon un-assuaged, however, as prosecutors added a bevy of charges under the Espionage Act that had a much more direct bearing on routine journalistic practice.

Other claims in the Yahoo story also bear directly on press freedom, beyond those immediately concerning the charges; indeed, many of them predate Trump’s time in office. As Dorfman, Naylor, and Isikoff report, the Obama administration, “fearful of the consequences for press freedom—and chastened by the blowback from its own aggressive leak hunts,” initially limited investigations into Assange and WikiLeaks, only for its approach to become more aggressive over time, following the group’s involvement in the Snowden leaks, in 2013, then again after its publication of hacked Democratic Party emails around the time of the 2016 election. In between times, intelligence officials reportedly lobbied Obama to bolster their investigative powers by classifying WikiLeaks as an “information broker,” and, troublingly, sought the same designation for Glenn Greenwald and Laura Poitras, two journalists at the heart of the Snowden story. (“I am not the least bit surprised that the CIA, a longtime authoritarian and antidemocratic institution, plotted to find a way to criminalize journalism,” Greenwald told Yahoo.) Trump’s administration, of course, had fewer First Amendment qualms than its predecessor. Then came Vault 7.

After Britain took Assange into custody, press-watchers debated old questions as to whether he can really be considered a journalist, and how much professional solidarity he deserves, especially in light of the historic rape claims against him and his links to Russia and its 2016 election-meddling. The espionage charges, by contrast, seemed to focus media minds to a greater extent, given their clear ramifications beyond Assange’s very specific circumstances. Some press advocates have reacted similarly to the details in the Yahoo story. The American Civil Liberties Union shared the article and reiterated its past call for the US to drop the charges against Assange on press-freedom grounds. The Freedom of the Press Foundation described the story as “shocking” and “disturbing,” and the CIA as “a disgrace”; Jameel Jaffer, the director of Columbia’s Knight First Amendment Institute said that the story was “mind-boggling,” adding, “the over-the-top headline actually manages to capture only a small fraction of the lunacy reported here.” Many media-watchers shared the story on Twitter, and numerous major news outlets, at home and abroad, covered or at least noted it.

Still, since its publication on Sunday, the story has hardly attracted wall-to-wall attention from other outlets: as far as I can see, the New York Times has yet to even mention it; CNN discussed it a couple of times on air yesterday, but not in prime time. There are a number of potential factors at play here, and they aren’t mutually exclusive. Rival outlets’ national-security reporters may still be working to corroborate the story, which is more useful than aggregation and takes time. Stories about national security, in general—and Assange, in particular—can be gnarly, and have been challenged before; the Yahoo article has itself already elicited some pushback. That said, Yahoo claims to have spoken with thirty former officials, eight of whom described the kidnapping plot and three of whom spoke of the assassination discussions; perhaps more to the point, TV talk shows, in particular, frequently give splashy billing to Trump scandal stories that seem less consequential and less extensively sourced. (The relentless cable coverage of a recent slew of books about Trump’s last days in office has often been a case in point.) It’s more than conceivable that—as with past stories about Assange—Yahoo’s claims haven’t yet gotten bigger billing because Assange is perceived to be an unsympathetic victim and because, unlike other examples of Trumpian demagoguery, the authoritarian state power at issue here has much deeper, broader roots than Trump himself, involving years of national-security policy under presidents of both parties.

If Yahoo’s reporting holds up, its bottom line is that senior US officials entertained extreme, violent, and extrajudicial responses to the publication of sensitive information. You don’t need to accept the probity of the publisher or the merits of the information to see the slippery slope here for press freedom—you need look, in fact, no farther than Greenwald and Poitras. The plans never came to fruition, but their high-level consideration would be bad enough—and the US government still very much is pursuing Assange on charges that could criminalize reporting, despite another recent change of administration; officials are currently appealing a British judge’s ruling that blocked the extradition of Assange on health grounds, and recently won the right to expand the terms of that appeal. The charges against Assange are as much a threat to press freedom under Biden as they were under Trump, yet for many media-watchers, they no longer seem close to front of mind.

Below, more on Assange:

- Questions: At a briefing on Friday, before the Yahoo story came out, Kimberly Halkett, a White House reporter for Al Jazeera English, asked Jen Psaki, the White House press secretary, why Biden hasn’t dropped the Trump-era charges against Assange given his many public statements in support of press freedom. Psaki defended the administration’s approach to press rights but said she didn’t have “anything new to say” about Assange, specifically, and referred Halkett to the Justice Department; Halkett countered, “This is something that I’ve emailed you about months ago, so there’s been time to discuss this.” At the briefing yesterday, after Yahoo’s story had dropped, Psaki did not field a single question on Assange.

- A counterpoint: Writing on her blog, Marcy Wheeler, a national-security journalist, took aim at the Yahoo story, arguing that it buried details debunking its assassination claim, a notion that “went nowhere,” in significant part because it would have been illegal. “This is a very long story that spends thousands of words admitting that its lead overstates how seriously this line of thought, particularly assassination, was pursued,” Wheeler wrote. “Pompeo is and was batshit crazy and I’m glad, for once, the lawyers managed to rein in the CIA Director. But this seems to be, largely, a story about crazy Mike Pompeo being reined in by lawyers.” (In 2018, Sam Thielman interviewed Wheeler for CJR.)

- Up north: Next week, a tribunal in Canada will consider whether Chelsea Manning—who leaked information to WikiLeaks and went to jail for it, only for Obama to eventually commute her sentence—should be allowed to enter the country. Canadian officials “are preparing to argue that Ms. Manning’s past crimes render her too dangerous to be allowed entry into the country,” the Globe and Mail reports. Manning’s lawyers argue that the bid “to block ‘one of the most well known whistleblowers in modern history’ would offend Canada’s constitutional and press freedoms.”

- Further reading: In 2017—around the time that, per Yahoo, the CIA’s campaign against WikiLeaks was ramping up—The New Yorker published a detailed profile of Assange by Raffi Khatchadourian, who repeatedly visited the embassy to speak with him. Assange once told Khatchadourian that WikiLeaks came “not to save journalism but to destroy it,” because it “doesn’t deserve to live. Too debased. Has to be ground down into ashes before a new structure can be formed. The basic asymmetric information between writer and reader just encourages lying.” The whole profile is still well worth a read.

Other notable stories:

- For CJR’s new magazine on political journalism after Trump, E. Tammy Kim profiled Real Change, a newspaper in Seattle that “models how to cover unhoused people—and puts money in their pockets.” If, “at its founding, in 1994, the newspaper had a unique grasp of the housing crisis, most media have since been forced to confront the problem,” Kim writes. Also for the magazine, Sam Sanders, of NPR, interrogates “the strange distinction journalists make between ‘hard’ and ‘soft’ news”—which “not only perpetuates inequality in the industry,” given that “hard” news has traditionally been pitched at straight white men, but “produces journalism that isn’t as informative and edifying as it could be.”

- Yesterday, a jury in New York found the R&B singer R. Kelly guilty of crimes including sex trafficking and the sexual exploitation of a child. He will be sentenced in May. As Alexandria Neason has written for CJR (and I recapped recently), dogged investigative reporting long ago shone a light on Kelly’s wrongdoing, though for years, swathes of the press downplayed it. The judge in the case banned journalists from the courtroom, citing COVID—a decision, CNN’s Sonia Moghe writes, that blocked reporters from observing key evidence and jurors’ reactions. Some reporters were finally let in to see the verdict.

- For Defector, Laura Wagner assessed a new initiative at the Times that will aim to build trust among readers, including by highlighting the paper’s journalistic practices. The project, Wagner writes, appears to be “a marketing exercise; the logical solution if you think, as Times honchos clearly do, that the problem of waning audience trust is located squarely in the audience’s lack of understanding of what New York Times journalism is, and not in anything having to do with the company’s approach to journalism itself.”

- Yesterday, the Times announced another new initiative, called the New York Times Corp: a “pipeline program for early-college students to receive career guidance from Times journalists over a multiyear period.” The program will target US-based students from underrepresented groups, including students of color and those from disadvantaged backgrounds. Nieman Lab’s Joshua Benton assessed the pros and cons of the program.

- Recently, the Wall Street Journal reported, as part of its “Facebook Files” series, on internal research showing that Instagram is harmful for many younger users. Facebook accused the Journal of mischaracterizing its research, but yesterday, Instagram paused work on a product aimed at kids; the company defended the concept, but said it wants to build “consensus” around it. Officials from both parties had previously criticized the idea.

- Yesterday, KATU, a TV station in Portland, Oregon, preempted its morning and afternoon news shows so that staff could attend a seminar, hosted by the Poynter Institute, on workplace stress and trauma. “In almost 25 years as a photojournalist, I’ve never seen a newsroom do this,” KATU’s Mike Warner tweeted. “But it’s been a crazy time… Personally speaking, seeing bodies daily gets to you.” The Oregonian has more.

- Today, Gimlet—in partnership with A24 and Crooked Media—is out with 544 Days, a new podcast in which Jason Rezaian, of the Post, tells his story of spending that amount of time in prison in Iran on bogus espionage charges. The podcast promises “a story about government and family and journalism, and what it took to free an innocent man… all while navigating the high-stakes world of nuclear diplomacy.” You can listen here.

- Last week, censors in Kenya banned I am Samuel, a documentary about a gay man; officials called the film “an attempt to use religion to advocate same-sex marriage” in a country where homosexuality remains illegal. Censors previously banned Rafiki, a fictional film about a lesbian relationship. The producers of I am Samuel hoped that their film’s nonfiction status would qualify it for press-freedom protections, without success.

- And Andrew Neil has spoken out about his acrimonious exit from GB News, a fledgling right-wing broadcaster in the UK that is already struggling. Neil tearfully told the Mail that his work helping to launch the channel brought him “close to a breakdown”; he also blasted its shambolic technical glitches, and alleged that colleagues once suggested putting “secret cameras in classrooms to show how left-wing the teachers were.”

From the magazine: Retail Politics

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.