On March 3, 1873, Congress passed what later became known as the Comstock Act, which made it illegal to send material by mail that was “obscene, lewd, or lascivious,” “indecent or immoral.” The wording was vague, and used to target anyone interested in exploring their sexuality, particularly women and queer people. Distributing information about birth control through the Postal Service became a federal offense and, as Michael Waters wrote for CJR in 2021, “police would regularly shut down publications that spoke too frankly about homosexuality.”

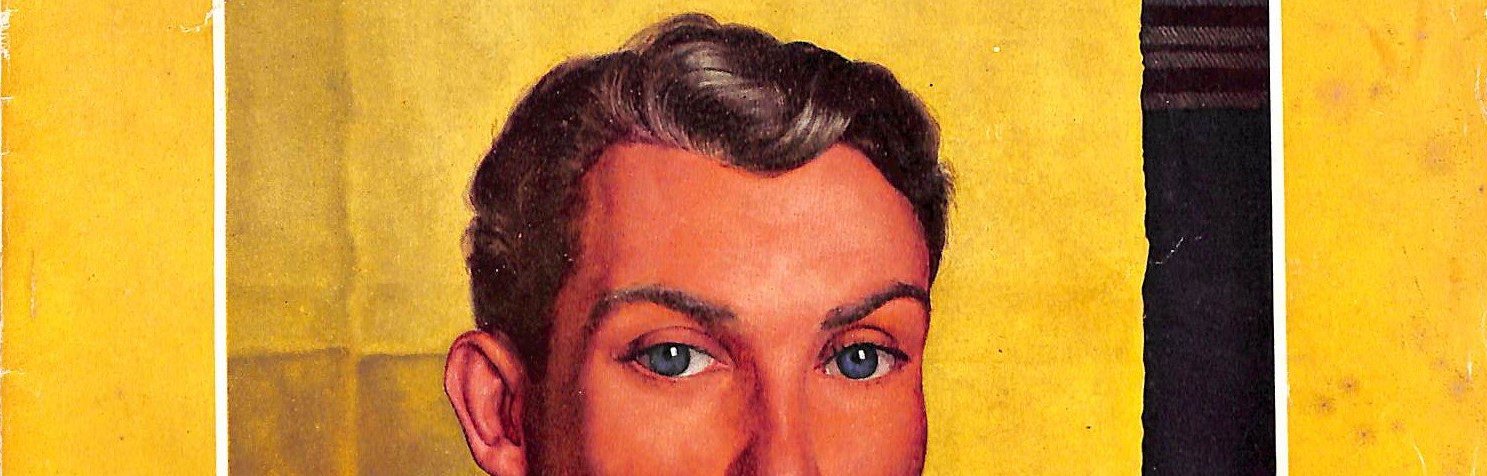

For queer media in the first half of the twentieth century, Waters observed, “very few publications explicitly said they were meant for the queer community.” But queer people made space for themselves anyway. Waters turned his attention to Bachelor magazine, which in 1937 shipped to newsstands across the United States and in Canada. “The magazine was hard to miss,” Waters wrote. “It was glossy, as big as Vogue, and its covers featured close-ups of famous men against garish backdrops.” Bachelor described its target reader as a “discerning cosmopolite,” a single man. “To a queer reader, that emphasis on bachelorhood brought to mind the phrase ‘confirmed bachelor’—a winking reference to a gay person,” Waters noted. Crucially, “the queer coding in magazines like Bachelor wasn’t just meant to wink at queer readers—it was also the only way a publication that wanted to discuss queerness could survive.”

Though producing an outlet for queer readers came with risks, Waters wrote, as time went on, Bachelor “only seemed to get more queer.” Its founder was Elizabeth Criswell, a woman from Circleville, Ohio, who had no evident “special knowledge of or relationship to the queer community.” Yet the magazine was based in New York, where she hired a number of queer staffers, who steered the editorial vision. If Criswell “intended Bachelor as a flipping-the-script of gender politics,” casting its gaze on men, Waters observed, her colleagues “created an opening for queer men to express their desires.”

Bachelor was not the only publication of its kind at the time, though it may have had the widest circulation. As the years went by, “hijacking of mainstream publications was essential to how queer people located one another,” Waters wrote. In the forties, the personal-ads section of a magazine called The Hobby Directory became a source of discovery and connection. At one point, federal officials charged a man named James McCabe with sending an “obscene letter” through the mail—because, as Waters discovered, “McCabe wrote to a man he had met in the pages of The Hobby Directory.”

This Pride Month, historical pangs of moral panic have felt all too current. A report released last week by the Anti-Defamation League and GLAAD revealed that, between June 2022 and April 2023, there were at least three hundred and fifty-six acts of anti-LGBTQ+ hatred across the country, including harassment, vandalism, and assault. Many of the perpetrators harmed drag performers, at a time when more than a dozen states have introduced bills to crack down on drag shows. All the while, state legislatures have carried out an assault on trans rights, including by restricting access to healthcare. According to the Trans Legislation Tracker, five hundred and sixty bills targeting trans people have been introduced in forty-nine states; eighty-three of those bills have passed. In Nebraska, lawmakers went after bodily autonomy of two kinds with a single ban: it blocked gender-affirming care for minors and made abortion illegal after twelve weeks. Major news organizations have often struggled to get the coverage right; in February, some two hundred journalists signed an open letter expressing concerns about how the New York Times reports on trans, nonbinary, and gender nonconforming people. As Graph Massara wrote recently for CJR, “Transgender people are increasingly in the news, and not always in a good way.”

Criminalizing queerness is not new, nor has telling queer stories in America ever been simple. Still, as Waters wrote, even a century ago, “queer people weren’t waiting for editorial approval to make space for themselves.” That, too, has not changed. You can read Waters’s piece here.

Other notable stories:

- Vanity Fair’s Charlotte Klein assessed how mainstream news outlets are covering the presidential candidacy of Robert F. Kennedy Jr., the conspiracy-spouting Kennedy scion, concluding that they are taking him “seriously, but cautiously.” Last night, Kennedy did a live town hall on NewsNation. CNN’s Oliver Darcy was not impressed, slamming the moderator, Elizabeth Vargas, for failing to hold Kennedy “accountable in a real way.”

- Yesterday, National Geographic—whose owner, Disney, has implemented several rounds of cuts in recent times—laid off all of its remaining staff writers and its audio department, eliminating around nineteen jobs, the Post’s Paul Farhi reports; going forward, article assignments will be “contracted out to freelancers or pieced together by editors.” Starting next year, the magazine will also disappear from US newsstands.

- Bloomberg’s Lucas Shaw and Gerry Smith report that Warner Bros. Discovery is planning to fold live CNN programming into its recently rebranded Max streaming service. The move “could be complicated” since TV providers that pay for cable rights are sensitive to online competition, though options exist for circumnavigating existing TV deals. (CNN’s last foray into streaming, CNN+, was abandoned last year.)

- Also for Bloomberg, Emma Ross-Thomas reports that journalists from that news organization, as well as from Reuters and the Wall Street Journal, have lost their accreditation to cover a forthcoming conference organized by the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries. OPEC blocked the same outlets from covering a policy meeting earlier this month; in both cases, the organization did not give a reason.

- And, drawing on data from a recent postmortem of the pandemic, David Wallace-Wells, of the Times, pushed back on what he calls the “myth” of partisan polarization during the early months of COVID in the US, arguing that, at the state and local levels, “red and blue authorities moved in quite close parallel,” and that “red and blue people did, too.” America’s experience in 2020, Wallace-Wells writes, has been “distorted in our memory.”