Recently, members of Britain’s political and media elite went to a swanky annual awards dinner held by The Spectator, a magazine of the Conservative establishment that once counted Boris Johnson as its editor. (Think the Gridiron Dinner in DC.) Attendees sipped champagne and cracked jokes at each other’s expense, but, according to Politico’s account, there was “an elephant in the room”: The Spectator, along with its sister paper, the Telegraph, is up for sale, and an investment fund linked to the government of the United Arab Emirates is close to buying it. Fraser Nelson, The Spectator’s editor, walked on stage to the theme music from Lawrence of Arabia. By the time of next year’s awards, he quipped, the magazine might be wealthy enough to afford Johnson as a guest (a nod to the lavish speaking fees that Johnson now commands).

Around the same time, Sultan Ahmed al-Jaber—the head of the UAE’s state oil company who is, somehow, also the president of COP28, a major United Nations climate summit that the UAE is hosting this year—was busy denying a report, from the BBC and the Centre for Climate Reporting, that the UAE planned to use the summit to broker fossil-fuel deals with various countries. Initially, officials did not deny the report, but on the eve of the summit, al-Jaber savaged it, telling reporters that the allegations were “an attempt to undermine” his work. “Please for once, respect who we are, respect what we have achieved,” he said. The remarks followed broader concerns that the UAE intended to use the summit to aggressively spin its global image. At one point, it reportedly issued rules barring journalists at the summit from reporting any stories that might offend the country’s rulers, though these were later withdrawn.

These two scenes are linked: al-Jaber reportedly oversees International Media Investments, the Emirati company that, in partnership with the US investment firm RedBird, is hoping to acquire The Spectator and the Telegraph. (Together, they operate as RedBird IMI.) And concerns about press freedom in the UAE—which have included its detention of journalists and critics, and its alleged surveillance of Jamal Khashoggi’s wife—have been widely cited by British opponents of the RedBird IMI takeover, especially among Conservatives. William Hague, a former foreign minister, praised the UAE in broad terms but called the prospect of the country owning UK publications “disturbing” and a step too far. (He recalled an occasion on which a senior Emirati berated him for the BBC’s coverage of the country, in language that allowed “no clear separation between private and public interest, or between national policy and media coverage.”) Journalists at The Spectator and the Telegraph have themselves insisted that their independence must be respected.

Some government lawmakers have gone so far as to call for the proposed deal to be reviewed on national-security grounds. But others have urged everyone to chill out. The latter camp has included Dominic Johnson, Britain’s investment minister, who last week welcomed Emirati officials to an investment conference in the UK and called the country “first class and extremely well run.” Also last week, Rishi Sunak, the prime minister, attended COP28 as the takeover controversy raged at home. Upsetting his hosts was not among his top priorities.

Late last week, Lucy Frazer, Sunak’s culture minister, moved to refer the proposed takeover for regulatory review, on both competition and public-interest grounds, “namely, the need for accurate presentation of news and free expression of opinion in newspapers.” The relevant regulators must report back by next month; if they express concerns, RedBird IMI will likely have to offer extra assurances if the deal is to be saved. The company has already insisted that IMI will be merely a “passive” investor with no managerial control, and that the two titles will retain their independence. In the meantime, it moved forward with plans to repay the debts of the publications’ parent company, the first step in the proposed takeover.

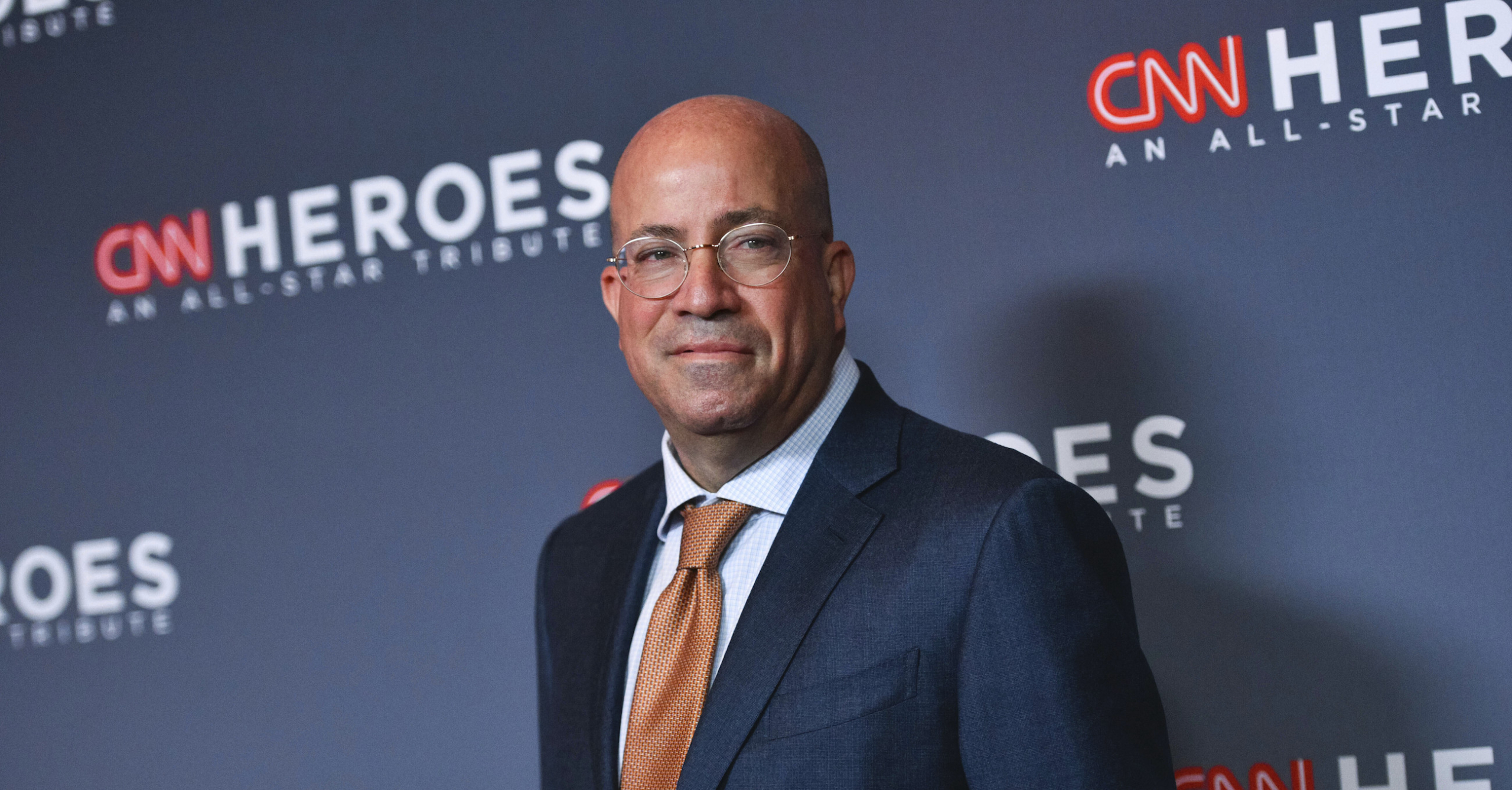

What will happen next is unclear. But beneath the surface-level—if by no means unimportant—focus on press freedom and democratic values already lies a messy tangle of other media stories, from the next act of Jeff Zucker (last seen being unceremoniously ousted as president of CNN) to bickering among RedBird IMI’s rival bidders and what it means to own a newspaper, anyway, in an era of decline for the medium. Most broadly, it is a story about globalization, not only of the media business but of whole swaths of the economy; the outsized current role of Gulf monarchies within that dynamic; and who makes for a “fit and proper” owner of a newsroom—and whether their nationality should have anything to do with it.

Financial entanglements between Gulf states and Western (and Western-style) media companies are not a wholly new development, but they would appear to be growing. It is, at least, in vogue to talk about them. Earlier this year, the media-business analyst Brian Morrissey noted that “more media companies are rationalizing their decisions to turn to Middle East autocracies” as venture investors steer clear of the media business; around the same time, Business Insider’s Claire Atkinson and Lucia Moses reported on a “steady trickle of US-based executives jetting to Gulf State capital cities” amid rising interest rates, the implosion of the crypto exchange FTX (which previously “spread dollars around the media business”), and sluggish ad revenue at home. The opening to the final season of the prestige drama Succession—always an astute observer of media trends—showed its fictional moguls preparing to pitch “petrostate” investors on a parody of a digital news brand. (“Substack-meets-Masterclass-meets-The Economist-meets-The–New Yorker.”)

IMI has been among the regional players getting in on the action. It invested in the launch of Grid, a buzzy news startup that was absorbed into The Messenger (itself a buzzy news startup) earlier this year; it also holds interests in Sky News Arabia, the European network Euronews, and a licensing deal to launch an Arabic business channel under CNN’s brand name. Zucker was involved in that deal while still at CNN; he has since helped to found RedBird IMI, which recently took a minority stake in Front Office Sports, a media company that covers the business of sports, and reportedly held discussions about investing in Puck and Semafor. Elsewhere, firms linked to Qatar have gotten involved with US production companies. And various entities linked to or owned by the Saudi state have interests in media companies including Bloomberg, Penske (now a significant investor in Vox), and Britain’s Independent and Evening Standard.

Moses has reported that the precise constellation of Gulf money in Western media companies can be hard to trace due to the opacity of the financial flows involved. And she found that many media dealmakers were reluctant to talk about it on the record—not least due to human-rights concerns, particularly around deals involving Saudi Arabia. Following the execution of the journalist Jamal Khashoggi in 2018, the kingdom briefly became a pariah on the world stage, not least among media executives. But that seems to have changed, if mostly on the quiet. Proponents of such deals justified them to Moses by arguing that they might help export Western values to the region—or by arguing that other parts of the world aren’t so innocent, either.

Gulf money isn’t only, or even most notably, flowing into the media industry. In recent years, much ink has been spilled on the massive regional investment in Western sports teams and leagues. (Sheikh Mansour bin Zayed bin Sultan Al Nahyan, who controls IMI, also owns the all-conquering English soccer club Manchester City.) Often, observers have attributed such investments to Gulf monarchies’ desire to wield influence and improve their global reputations. (“We’ve had sportswashing,” a source at the Telegraph fretted to The Guardian. “Are we now seeing newswashing?”) Other analysts have cited a more complex range of motivations, from a desire for economic diversification to attempts to boost tourism and public health.

When it comes to news-media investments, concerns about foreign influence are, of course, particularly acute, and sometimes concrete. Earlier this year, The Guardian’s Jim Waterson reported that Vice killed stories about Saudi transgender rights campaigners and the kingdom’s powerful crown prince, Mohammed bin Salman, after managers expressed concerns that publication might endanger company staff inside the country. An executive at a media company with Middle Eastern ties told Moses that they worry about the potential for self-censorship among their staff. Writing last week in the context of the proposed Spectator and Telegraph takeover, Robert Shrimsley, of the Financial Times, argued that it would be “naive” to expect the titles to publish coverage inimical to the UAE’s interests, despite IMI’s pledges of “passive” investment. (When Western media companies have publicly addressed Gulf financing, they have typically insisted that it has no impact on their editorial practices.)

Over the summer, a bank effectively seized The Spectator and the Telegraph from their owners, the Barclay family, over unpaid debts. The race to buy the titles quickly resembled a “murderers’ row of media barons,” as Vanity Fair’s Joe Pompeo put it. Among those reported to be interested were Lord Rothermere, the owner of the right-wing Mail; Paul Marshall, an investor in the upstart right-wing network GB News; and, of course, Rupert Murdoch. It’s safe to say that these moguls courted the titles less for their flush financial potential than their political influence as bibles of the (still just about governing) Conservative Party. It’s also safe to say, as Shrimsley argued, that they and Britain’s other existing press barons are hardly, between them, paragons of virtue. And in several of their cases—especially that of Murdoch—an acquisition of The Spectator and the Telegraph would raise serious concerns about media competition and pluralism.

Zucker has argued that his rival bidders’ sniping at the UAE’s press-freedom record is hypocritical, insinuating that Marshall, for one, previously wanted in on the RedBird IMI deal. (Marshall has denied this.) In general, the opposition to the takeover in the UK has at times felt parochial, or at least exceptionalist—like King Canute commanding that the rising tide of globalization be reversed. As I wrote earlier this year, viewing the media world through rigid national prisms no longer seems tenable. That is not in and of itself a bad thing.

None of this is to say that Emirati officials are suitable owners for a major media company—their involvement at the very least sends a symbolic message about press freedom, climate, and myriad other concerns—but to say that, within the commercial, highest-bidder media landscape we have, it’s possible to imagine British-based owners who might be even worse, especially if RedBird IMI is sincere about the UAE’s passivity in the deal. “This is me,” Zucker told the Telegraph last week. “This is not IMI or Abu Dhabi.” Not that his words will necessarily have assuaged the paper’s conservative readers. If online comments are any guide, some of them object more to Zucker’s past running of CNN than any tie-up with the UAE.

Other notable stories:

- The Atlantic is out with a new issue assessing what Donald Trump is likely to do if he is reelected to the White House, with twenty-four contributors assessing his impact on everything from NATO to the courts. Trump’s second term, they collectively conclude, “would be much worse” than his first. In an essay focused on journalism, George Packer argues that Trump has repeatedly entrapped the press and could render it “irrelevant” in a second term. “The first time around, Trump’s attempts to use presidential power against the media were desultory,” Packer writes. Now “it’s not hard to imagine Trump breaking laws to go after journalists, seeking embarrassing personal information on his most effective pursuers” while also leveraging legal assaults and economic pressure.

- For CJR and the Tow Center for Digital Journalism, Meghnad Bose, Matthew Danbury and Dhrumil Mehta report that Trump is continuing to dominate cable news. “According to closed-captioning data from the Internet Archive’s TV News Archive, Trump has been mentioned in 38 percent more clips on the big three national cable news networks—CNN, MSNBC and Fox News—than President Joe Biden has this year so far,” Bose, Danbury, and Mehta write. “Journalists who covered the 2016 election cycle may be experiencing some déjà vu. But there is one significant difference. Fox News viewers are seeing more coverage about the incumbent Democratic president.”

- Yesterday, Spotify announced that it is cutting around fifteen hundred staffers, equivalent to nearly a fifth of the workforce, after already cutting around eight hundred positions across two rounds of layoffs earlier this year, many of them in its podcasting department. According to Bloomberg’s Ashley Carman, the company is also canceling two popular podcasts: Heavyweight and Stolen, the latter of which won a Pulitzer Prize earlier this year. Per the Hollywood Reporter, the cancellations were “unrelated” to the other layoffs “but rather come as the platform tempers its investment in the podcast space.”

- Hearst acquired Puzzmo, a puzzle platform that bills itself as “a reimagining of the classic newspaper games page,” The Verge’s Andrew Webster reports. As part of the deal, Puzzmo will “begin rolling out to readers of more than 50 Hearst publications, including the San Francisco Chronicle and Popular Mechanics.” Webster writes. “Additionally, Hearst will be licensing out Puzzmo games to other publishers.” The acquisition puts Hearst into competition with the Times, which acquired Wordle last year.

- And at least nine relatives of Ibrahim Dahman—a producer for CNN who covered Israel’s war with Gaza before escaping into Egypt with his immediate family last month—were killed in an Israeli air strike on Sunday. The same day, a separate strike wiped out his childhood home. “I left all my memories, my belongings, and the gifts that my bosses sent me at work in this house,” he said, “all of which were lost under the rubble now.”

ICYMI: George Santos’s greatest grift

Jon Allsop is a freelance journalist whose work has appeared in the New York Review of Books, Foreign Policy, and The Nation, among other outlets. He writes CJR’s newsletter The Media Today. Find him on Twitter @Jon_Allsop.