Sign up for the daily CJR newsletter.

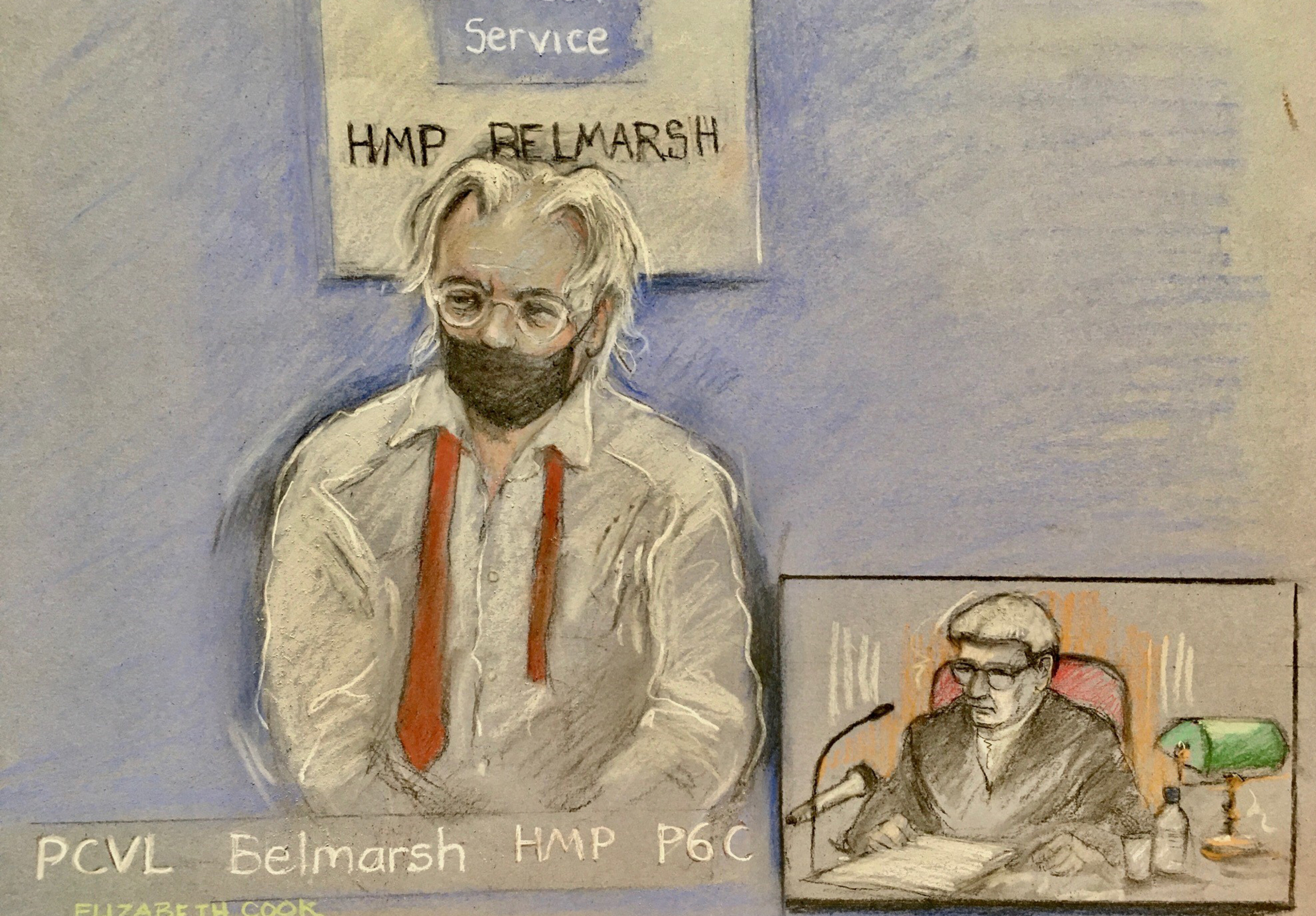

In recent days, we saw significant movement in a case involving federal charges under the Espionage Act against an individual alleged to have mishandled highly sensitive official information. Julian Assange—the founder of WikiLeaks, which, in the early 2010s, published a trove of leaked defense and diplomatic documents—has been fighting his extradition from the UK, where he is currently in prison, to face the espionage charges in the US; in 2021, a judge ruled in his favor, citing risks to his mental health, but a higher court overturned that verdict, and, earlier this month, denied him permission to appeal, ruling that he had not raised “any properly arguable point.” Assange’s supporters say that the extradition threatens his human rights and that the charges he faces in the US criminalize truth-telling. In any case, he plans to fight on.

Recent days, of course, also brought a raft of fresh Espionage Act charges against another individual: Donald Trump, who stands accused under the act of willfully retaining classified materials after leaving the White House in 2021. He has also been charged, under different statutes, with concealing the documents from federal law enforcement officials, making false statements about them, and conspiring with an aide to obstruct the investigation in the case.

Trump and his allies have since whined that the charges amount to targeted political persecution and are incorrectly predicated: Trump himself said that the Espionage Act is designed for the prosecution of “traitors and spies,” and that he is nothing of the sort; Lindsey Graham, the Republican senator from South Carolina, acknowledged that Trump may have committed wrongdoing, but insisted, “He is not a spy. He is overcharged.” The word espionage, of course, does typically refer to spying. But as many observers have pointed out, the Espionage Act (with its capital E and A) is much broader in scope than this classical definition might suggest—not only in theory, but in practice, not least under the presidency of Donald Trump. According to the CNN fact checker Daniel Dale, at least seven comparatively obscure individuals have been convicted of retaining sensitive documents since Trump took office in 2017; just this month, Robert Birchum, an Air Force intelligence officer, was sentenced to three years in prison after acknowledging that he stashed hundreds of papers at his home and in other locations. And presidents—again, very much including Trump—have increasingly wielded the act against leakers who have disseminated such materials, either to the news media or online. Just last week, prosecutors brought additional Espionage Act charges against Jack Teixeira, the Air National Guardsman accused of posting classified information to Discord.

Since being charged, Trump has been mentioned in the same breath as various other leakers, including Reality Winner, who was jailed for passing proof of Russian election interference to The Intercept; Daniel Hale, who was jailed for leaking information about America’s use of drone warfare, also to The Intercept; and Teixeira. (Writing for the New York Times, Oona A. Hathaway, a Yale law professor, noted suggestions that both Trump and Teixeira may have kept hold of classified information to win clout among friends.) This vein of commentary, particularly as applied to the likes of Winner and Hale, risks concealing obvious, important differences: Trump is in no way a whistleblower acting in the public interest, and he has not been accused of leaking or widely disseminating the documents he retained. (James Risen, a veteran national-security reporter at The Intercept, called such comparisons “facile.”) Yet Trump has at least been accused of bragging to acquaintances about retaining classified material. And his case has, at the very least, begun to spark a broader conversation around the Espionage Act—a conversation to which whistleblowing, and by extension journalism, are absolutely central.

The Espionage Act dates to World War I. It was first passed in 1917 and subsequently bolstered to clamp down on supposedly seditious anti-war dissent, including among members of the press; Victor Berger, a newspaper editor turned Socialist congressman, was convicted under the act, as was the activist and writer Emma Goldman. (Publications linked to both individuals were denied mail privileges by the postal service.) Provisions targeting dissent were later struck off, but the informational core of the Espionage Act survived and, since the fifties, has not been significantly revised. (The act predates the modern classification system and so applies to the broader category of national-defense information—though these days, documents falling under the act are typically classified.) During the Cold War, the act was wielded against alleged spies like Julius and Ethel Rosenberg, who were accused of passing nuclear and other secrets to the Soviet Union and eventually handed the death penalty. (As fate would have it, yesterday marked the seventieth anniversary of their executions.) Prosecutions of whistleblowers under the Espionage Act were once rare: according to Heidi Kitrosser, a law professor at Northwestern University, the act had only been used to target sources for news organizations on three occasions by the time George W. Bush left office in 2009. The Obama administration, however, aggressively went after government leakers. Trump maintained something like the same pace.

Prosecutions of leakers haven’t always invoked the Espionage Act, but they often have, and critics of the law, from press-freedom advocates to progressive members of Congress, have repeatedly argued that it should be amended to enshrine some degree of legal protection for whistleblowers who leak information in the public interest. Others have argued that the act in its present form is unconstitutional and should be thrown out by the courts. Around the time that the recent charges against Trump were unsealed, Ryan Grim, The Intercept’s DC bureau chief, pointed out that Daniel Ellsberg—the whistleblower who leaked the Pentagon Papers to the press in the early seventies and was charged under the Espionage Act, only for the case to be thrown out—has often made this argument. On Friday, Ellsberg was in the news again—he died, aged ninety-two. Charlie Savage, of the Times, subsequently reported that Ellsberg had sought, as his life neared its end, to get charged again under the Espionage Act, as a vehicle to try to convince the Supreme Court that it violates the First Amendment. In 2021, Ellsberg passed Savage a decades-old classified record that was still in his possession, concerning US plans for a nuclear strike on China. Savage published a story, but Ellsberg was never charged.

Even many critics of the Espionage Act don’t believe that it is unconstitutional in every sense; Jameel Jaffer, the director of Columbia’s Knight First Amendment Institute, told MSNBC’s Mehdi Hasan last week that he doesn’t know of “any First Amendment advocate who’s ever said that,” adding that “the argument has always been that the act is unconstitutional as applied to publishers and whistleblowers.” Who gets to call themselves a publisher or a whistleblower can be a thorny question, as Jaffer noted. Trump’s alleged conduct clearly doesn’t place him in either bracket, and journalists have no obvious professional interest in defending its legality. The problem here is that—however different the cases of Trump and, say, Winner or Hale might be—the Espionage Act currently leaves no room to assess motivation or public interest. As Thomas Drake, a former top national-security official turned whistleblower, put it, “the deep irony is that the Espionage Act, in its contemporary use, can’t tell Trump and Hale apart.”

The closer you look, the hazier the lines here become; in his defense of Trump against claims of “espionage” as spying, for instance, Graham seemed to elide, in his definition of that term, leaks intended to “damage this country” to both foreign powers and news organizations. At the very least, much as the initial probe into Trump’s mishandling of classified documents opened an adjacent, wider media debate as to whether the US government classifies too much information, we should hope that the Espionage Act charges against Trump, however solid they prove to be, might shine a broader spotlight on the act itself, and whether its recent application—not least, but not only, by Trump—has served the public good. As Kitrosser put it in an article for Lawfare, “at the same time that the Trump administration’s prosecution record undermines the notion that Trump’s indictment is political persecution, both things should lead us to rethink the Espionage Act’s capaciousness. Indeed, the gulf between Trump’s alleged behavior and that of the media sources prosecuted by his administration illustrates the extraordinary breadth of the act.”

Ellsberg once warned Savage that the Espionage Act’s extraordinary breadth could in theory allow the government to weaponize it not only against those who leak documents to the press, but the reporters who publish them, or even—perhaps—those who read their articles and don’t immediately alert the authorities. Already, such fears are not purely theoretical: press-freedom groups have repeatedly warned that the Espionage Act charges against Assange cross the Rubicon by criminalizing activities that constitute routine reporting techniques. That it was Trump’s administration that filed these charges may look, in light of last week’s news, to be ironic. But the Biden administration has continued to press them. As the Freedom of the Press Foundation noted after the British court’s recent rejection of Assange’s plan to appeal, his case is “not about one individual, it’s about freedom of the press.” Trump’s case is not about freedom of the press. But the Espionage Act is, and the debate around it is far bigger than Trump, too.

Other notable stories:

- Last year, the homes of Lauren Chooljian, a journalist at New Hampshire Public Radio; her editor; and her parents were vandalized after Chooljian reported on allegations of sexual misconduct against the founder of a network of rehab centers. Now three men, one of whom remains at large, have been charged in the case, with investigators claiming that they conspired to “retaliate” against NHPR with a close associate of the founder.

- Meanwhile, a jury in Asheville, North Carolina, found Matilda Bliss and Veronica Coit, two reporters with the Asheville Blade, guilty of trespassing after they covered the police clearing of a homeless encampment in the city in 2021. According to the Asheville Citizen Times, a judge instructed the jury not to consider Bliss’s and Coit’s First Amendment rights after ruling that they were not infringed. Bliss and Coit plan to appeal.

- Last week—after Belle Adelman-Cannon, a teenager who was gender fluid and used she/he/they pronouns, was struck and killed by a school bus in New Orleans—the local Times-Picayune/Advocate published a letter to the editor referring to Adelman-Cannon’s pronouns as an “inner confusion” and criticizing the paper for using them. The paper subsequently retracted the letter and apologized to Adelman-Cannon’s family.

- Last week, I reported in this newsletter on the imminent firing of Geoffroy Lejeune, the editor of the hard-right French magazine Valeurs Actuelles, amid a broader debate about its positioning on the country’s far right and perceived closeness to the commentator turned presidential candidate Éric Zemmour. Now Lejeune’s departure has been confirmed. He will be replaced by his deputy, Tugdual Denis. Le Monde has more.

- And, after Prince Harry and Meghan Markle’s production company severed ties with Spotify, Bill Simmons, a Spotify podcasting executive, blasted the pair on his show, calling them “fucking grifters.” Harry and Meghan only produced one podcast for Spotify, a show hosted by Meghan, and that only ran to twelve episodes—too few, the Wall Street Journal reports, to meet productivity benchmarks in their Spotify contract.

ICYMI: The tech platforms have surrendered in the fight over election-related misinformation

Update: This post has been updated to clarify a reference to accusations about Trump’s dissemination of classified documents.

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.