Sign up for the daily CJR newsletter.

Last week, Joe Lieberman died unexpectedly, following a fall. He was eighty-two. Obituaries and other stories about the news often led with Lieberman’s legacy as a senator for Connecticut and vice presidential nominee—he was the first Jewish candidate for the latter office, as Al Gore’s running mate in 2000—as well as tributes to his “mensch”-ness, his authenticity, and his independence. The latter theme came across particularly strongly: after running alongside Gore, Lieberman moved away from the Democratic Party (though he would have said that it moved away from him), won reelection to the Senate as an independent, and was considered to be the Republican John McCain’s running mate in 2008. Lieberman “was never shy about veering from the party line,” the AP wrote. The Washington Post described him as “doggedly independent.”

Perhaps surprisingly, given its relevance to this theme, these and other obituaries made only sparing reference to Lieberman’s most recent political legacy: as a leading light of No Labels, the nominally centrist group that has courted significant media coverage (and no little controversy) over the past year as it has explored running a bipartisan unity ticket in the presidential election in November. (The New York Times’ obit said that Lieberman wore “no labels easily” some twenty-five paragraphs before getting to his involvement with the capitalized organization of that name.) Not that there was no coverage of this angle: the AP described Lieberman’s death as an “irreplaceable loss” for the group, one that “injects a new level of uncertainty” into its plans. Among other things, the AP noted, Lieberman was the group’s chief defender in the media. Less than a week before his death, he insisted to Bloomberg that “this is the moment” for a unity ticket—but also acknowledged that finding candidates was “not easy.”

Even aside from Lieberman’s death, there were signs last week that the lengthy No Labels news cycle might finally be running out of steam. Chris Christie, a Donald Trump ally turned antagonist, told the Post that he would not be running as the group’s candidate—he considered the idea, but concluded that a bid would be onerous, and risked letting Trump back into the White House—adding his name to the growing list of perceived moderates (Joe Manchin; Larry Hogan; Nikki Haley) to have turned the opportunity down. (Last month, No Labels pledged to decide on a ticket by early April; April is now here, and a No Labels ticket is not.) Alexander Burns, the head of news at Politico, wrote in his column that the group is approaching its hunt all wrong—going after establishment types when it should be courting charismatic outsiders. (“My point here is not to belittle No Labels” since “whatever else there is to say about the group, it has a formidable tolerance for ridicule,” Burns wrote, before suggesting that it tap Ramit Sethi, Dave Chappelle, or Julia Louis-Dreyfus.) The USA Today humor columnist Rex Huppke likened No Labels to the “kid at recess who nobody picks for a kickball team” and jokingly proposed himself as its candidate. His proposed platform: “For the love of God, please vote for Joe Biden.”

Still, for now, No Labels continues to attract media attention. And the broader idea of a potent third-party challenge to Biden and Trump remains a huge story, in a country where many voters remain turned off by the prospect of that matchup and where various candidates beyond No Labels—of the left, right, both, and neither—are already running. Last week alone, the Post convened a Q&A with readers to discuss the possible impact of third-party candidacies on the race, while the Times made a video addressing the same question. (“If there was ever an election where a third-party candidate could make a real impact,” a reporter said, “it’s this one.”) Meanwhile, a Texas math teacher and self-described political centrist named Dustin Ebey legally changed his name to “Literally Anybody Else” and declared that he is running for president, attracting a predictable flurry of media interest. “I don’t want to be a gimmick for the rest of my life,” Ebe—sorry, Literally Anybody Else told CNN. “It’s meant to get your attention.”

Some recent coverage has addressed the bigger-picture ramifications of the surge in third-party interest. (“It feels like the last four years in America have been a time to really question the structures of government and the way things have been working for decades,” the Times video continued, over footage of protesters holding signs including “STOP THE STEAL,” “FAILED COUP,” and “STAND WITH PALESTINE.”) Much of it, though, has been concerned with the relative minutiae of the electoral process: polling, ballot access, fundraising, personnel. And, of course, whether Biden/Trump stands to lose/gain (delete as appropriate) from the phenomenon.

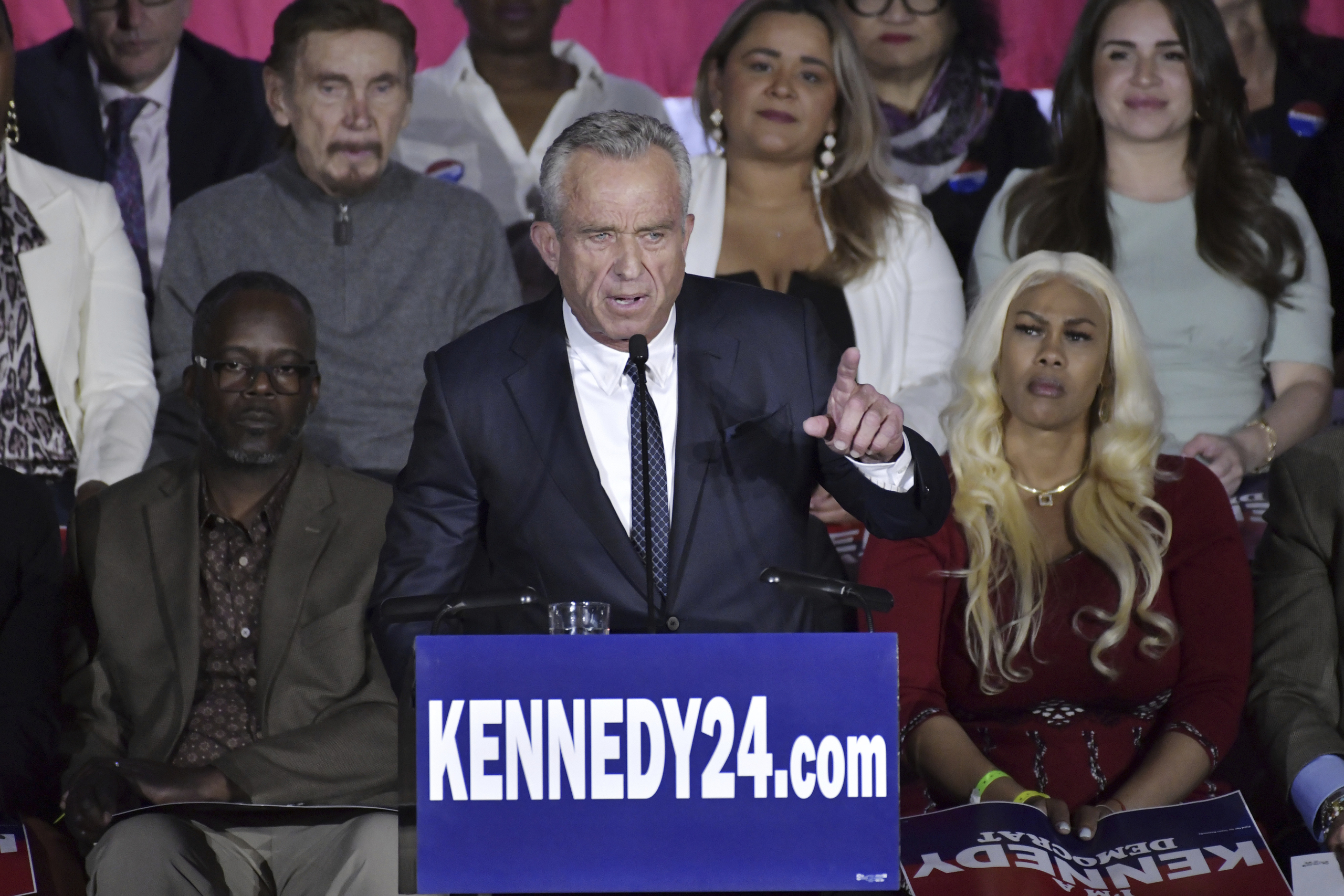

No one candidate, perhaps, has better encapsulated these divergent coverage dynamics than Robert F. Kennedy Jr., who initially jumped into the race as a Democrat last year before switching to run as an independent, and is having a media moment (again). Politico’s influential Playbook newsletter noted last weekend that Kennedy “has been everywhere” of late—a result, the authors suggested, of a recharged media strategy on his part or boredom with the Biden-Trump rematch among reporters—before running through three “angles” to the Kennedy story: “spoiler,” “money and enthusiasm,” “running mate.” Since then (in what an NPR analyst described as one of the week’s “most anticipated stories in politics”) Kennedy did tap a running mate: Nicole Shanahan, an attorney who is not especially well-known to the press or public but is especially wealthy. (The press quickly published explainers, like Politico’s “55 Things You Need to Know About Nicole Shanahan.”) Reporters covered Kennedy’s apparent ballot-access woes in Nevada and flirtations with the Libertarian ticket. And journalists and pundits continued to debate whether his candidacy stands to hurt Biden or Trump the most.

The coverage of third-party candidates in general—and Kennedy in particular, as I wrote last year—has sometimes fed into media tropes that I have frequently criticized in this newsletter: an obsessive focus on the horse race; what one might call negative bothsidesism (or the idea that third-party options are surging because both main parties are similarly distasteful); the unfortunate reality that attention-seekers with fame and/or money can get what they’re after just by running for president.

But dodging these tropes can be complicated when covering political insurgents (as I also wrote last year with regard to coverage of Kennedy’s campaign). Attention-seekers can exploit a presidential run to get attention or build a brand—but the press should scrutinize those running for president (especially the likes of Kennedy, with his conspiratorial views on vaccines and other key questions). Many people are fed up with both main parties. And in any close election, even relatively unpopular third-party candidates can change the result by playing spoiler. (Pundits often point to the case of Jill Stein, the Green Party candidate, who appeared to do just this in Wisconsin in 2016. Incidentally, she, too, is among those running this year.) If horse-race media coverage is a dog bites man phenomenon (to mix journalistic animal metaphors), then a multi-horse pileup halfway down the track is, at least, man bites dog.

I’ve also criticized political journalists for structuring their work rigidly around the two-party system as it exists now, a framing I see as being rooted in both journalistic expediency and the assumption (as I put it in 2021) “not only that two parties can collectively represent a huge and diverse country, but that those parties should, as a matter of moral principle, strive as much as possible to agree.” Devoting more coverage to third parties and independents can help to counter this myopic tendency, which can lead to coverage that extols bipartisanship as an end in itself without interrogating whether the bipartisan system is actually delivering. And yet this system is very real, not least in an electoral sense—and so coverage of third parties must, to some extent, be structured around it, even if this can, in turn, encourage the types of third-party coverage I just criticized above. All of which creates a dilemma.

Not an unsolvable one, though—as I see it, there are several ways we can cover third-party candidacies fruitfully. One is to pay close attention to the history of such candidacies and what they can still tell us—not only in terms of how they affected the final outcome, but what they said about the country and its mood at the time. Recently, the history podcast The Road to Now has done just this, recording a series of insightful conversations with experts about the impact—and enduring lessons—of third-party candidacies dating all the way back to the election of 1824. (In part, the series is framed as an explicit response to current media coverage of past third-party bids, with the hosts arguing that modern reporters “don’t do very good history a lot of the time”—throwing out “references that don’t make sense” and missing pertinent parallels.)

One consistent theme of the series—the idea that the US party system has historically fluctuated, rather than existing in some immutable, inevitable equilibrium—points to a second suggestion: that reporters today should recognize that, one day, future history-podcast hosts might see the partisan dynamics of our time very differently from our assessment of them in the present. This isn’t to say reporters should indulge in fantasy (about, say, the likelihood of Kennedy’s campaign actually winning) or take too long-term a view; as I’ve written before, history and journalism have different demands. But we should show both humility and imagination in keeping an open mind about the third parties we’re covering. Where America is now is not where it’s always been, or necessarily where it’s headed.

At the same time, we should interrogate what third-party candidates in this election are substantively offering, and whether they’re meeting a real popular demand or gaming the media for attention (not that these outcomes are mutually exclusive, of course). There is certainly a demand for Kennedy’s views—but as I wrote last year, coverage of the conspiracy-as-zeitgeist can sometimes overstate it. And the mainstream press—which, as I noted above, often tends to romanticize the notion of bipartisanship—can certainly overstate the appeal of a No Labels–type offering, one rooted in an establishment centrism that sounds intuitively sensible to many journalists and pundits in Washington, but may have much less of a constituency beyond.

Nearly a year ago, when the No Labels presidential news cycle was still in its relative infancy, Astead Herndon, the host of the Times’ political podcast The Run-Up, interviewed Lieberman and showed how to ask tough questions about a third-party project while taking the concept itself seriously. Herndon asked about electoral dynamics like potential candidates, but also grilled Lieberman and a colleague as to their actual policy offerings and political positioning, which emerged as fuzzy. And Herndon used interviews with voters to illustrate the—often very weird—range of views out there in the country, which would not slot neatly into a three-party system, never mind a two-party one. No Labels “diagnosed the central reality of this moment,” Herndon concluded. “But their ability to provide a solution is much less clear.”

Other notable stories:

- Over the weekend, Republican politicians and their allies in right-wing media slammed the Biden White House for declaring Easter Sunday as Trans Visibility Day—even though the latter is always celebrated on March 31 and the timing of Easter this year was a coincidence. A Trump spokesperson further alleged that the Biden administration had banned children from submitting “religious egg designs” for the annual White House Easter Egg Roll, which will take place today—but spokespeople for the American Egg Board, which helps organize the event, scrambled (sorry) to rebut that claim, noting that such prohibitions have been in place since 1976, including under Trump’s presidency. (It was, as Politico’s Playbook newsletter noted, a “weird news cycle.”)

- The Baltimore Banner’s Abby Zimmardi and Jessica Gallagher tracked down and spoke with Larry Desantis, a local bakery employee who was one of the last people seen driving across the Francis Scott Key Bridge before it collapsed last week. A cargo ship crashed into the bridge approximately a minute after Desantis drove off of it, though he says that “he didn’t hear the boom of the bridge crashing down because he had a SiriusXM radio channel playing,” Zimmardi and Gallagher write. He did, however, find it weird that the road behind him was empty, and was eventually informed of the collapse when he fielded concerned calls from a colleague and from Maryland transport police.

- Last week, Kim Mulkey, the head coach of the women’s basketball team at Louisiana State University, made headlines when she threatened to sue the Washington Post over a supposed forthcoming “hit piece” about her. Over the weekend, the story, by Kent Babb, was published; it characterized Mulkey as combative and divisive, but, as CNN noted, lacked “the type of bombshell revelations that many were expecting” following Mulkey’s prepublication tirade. Meanwhile, the LA Times made changes to an op-ed referring to the LSU team as “villains” after Mulkey publicly criticized it as offensive.

- For Air Mail, Rich Cohen profiled Fergie Chambers, a onetime heir to the Cox media empire who cut ties with his family, settled for two hundred and fifty million dollars, and promised to use the cash to “fund the revolution” from the radical left. Chambers “has been the object of a scion’s share of recent media attention,” Cohen writes. Reading each of the recent articles about him, “we once again learn the story of his strange wayward career, which unfurls less like a typical C.V. than a folk song.”

- And, according to Politico, journalists covering the president (and other passengers) keep stealing mementos from Air Force One—a problem that has gotten so bad that the White House Correspondents’ Association recently reminded members not to do it. “The rampant thievery makes sense,” Politico notes, “when you remember that Washington is a town populated by a lot of ambitious, status-seeking dorks.”

ICYMI: The Ronna McDaniel incident reveals a deeper dilemma for journalism

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.