Just about every television in Europe has a “teletext” button. Push the button on your television remote and you’re digitally transported to the early 1980s. Against a black background, brief news dispatches are spelled out in bright, thickly pixelated text reminiscent of an Atari game title screen. As old-fashioned as it looks, the news you see isn’t from the ’80s—it’s from right now. Almost four decades after it started, teletext remains almost exactly the same now as it was at its birth.

Teletext, first used by the BBC in 1972, is a technology that was developed to take advantage of a previously unused bit of digital space between picture frames. In this space, programmers could send extra information to television sets besides actual TV shows—closed captioning text, for instance, or news alerts. Eventually the service grew to include hundreds of pages of text, from weather reports to sports scores to airline information. And the technology spread to other countries, too, though experiments with teletext in the US were brief and ultimately unsuccessful.

Today, many teletext services throughout the world are on the wane, as they are replaced by sleeker news services online and mobile technology. In the United Kingdom—where teletext was born—the BBC will shut down its teletext service later this year, to go along with its switch from analog to digital service. But, curiously, teletext is still going strong in Scandinavia—much to its providers’ bemusement.

Eva Hamilton, CEO of Sveriges Television, Sweden’s public television network, says that SVT’s version of teletext is “by far the biggest media in Sweden.” She laughs and says, “We say every year, ‘it’s going to decrease’…it doesn’t!” Two million people in Sweden access teletext through their televisions every day, and about 3.5 million do so every week. Sweden’s total population is only 9.4 million. Finland and Norway have similar percentages of the population using teletext regularly: about a fifth of the country every day, and about a third every week. Denmark’s share is even larger: 2.6 million people access teletext every week, which is almost half of the country’s population.

“We’ve been waiting for it to die for ten, fifteen years,” says Erik Bolstad, head of new media services for Norway’s public television and radio network, “and it just doesn’t.”

This all may seem surprising—especially if you take into consideration that the Scandinavian population is among the most web-connected in the world, has among the highest news readership in the world, and has the most newspapers per capita in the world catering to them. With so much media to choose from, why is this old-fashioned, clunky-looking medium still so popular?

One possible reason: old habits die hard. When teletext arrived in Scandinavian homes in the late 1970s, news was delivered via radio, television, and daily newspaper. Teletext was a fast, easy way to check headlines and sports scores. When personal computers made their way into homes, early dial-up connections were frustratingly slow, of course, so teletext was still preferable. Now, generations that grew up with the teletext habit continue to use the service. And even with the development of mobile technology and widespread broadband Internet access, teletext’s old audience hasn’t abandoned it; they just use it in addition to online news sources.

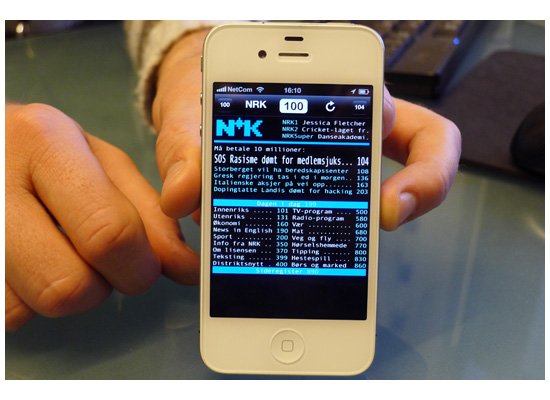

In fact, all of the major publicly funded broadcast networks in Scandinavia have now put their teletext feeds online: Finland’s YLE, Norway’s NRK, Denmark’s DR, and Sweden’s SVT. The format of the online version remains the same as the television version, with pages accessed one at a time through a three-digit page number entered at the top of the screen. Despite its availability online, though, most news producers in these networks say that more than 90 percent of their regular teletext audience still accesses it through their television sets.

“I think the reason teletext is still so popular is that it is so accessible,” says Bolstad. “It takes a shorter time for you to push one button and see whether anything has happened in the world than it does for you to go to a news site.”

Many regulars say teletext is the first thing they check in the morning and the last thing they check before bed. It’s reliable, easy to use, and only gives them the most important news and information, uncluttered by ads or moving parts. As Freja Salo, a member of the SVT’s social media strategy team, puts it, “If something is on the teletext, it’s really, like, ‘proper news.’”

Teletext isn’t just incredibly simple to use, it’s also very simple to produce. In the newsroom, one or two people can be working on condensing the most important news into concise teletext entries while the rest of the team fills out online news stories. Both versions can go up simultaneously—although the online version will likely be filled out, while the briefer teletext version will remain just a bulletin. In Denmark’s DR, the teletext feed and the online news feed share the same CMS with the network’s own wire service, so the updates to the teletext system happen more or less automatically. In other newsrooms, like NRK’s in Norway, a writer still types the teletext in manually.

“The beauty of it is that you really have to concentrate to get the whole story across in such a limited format,” says Bolstad. “There are thirty-nine characters per line. You can’t get in forty.” (Both Twitter users and headline-writers of print publications can probably relate.)

It’s also cheap. Right now, SVT is making considerable investments into its sleek new online video player, and likewise, its sister public broadcaster Sveriges Radio into its 24-hour online news radio network, Alltid Nyheter. Yet teletext keeps plugging along, without requiring any more money or staff time than it ever has in the past. There are about half a dozen people working on SVT’s teletext version within a twenty-four hour period. Of these teletext veterans—mostly older gentlemen—CEO Eva Hamilton says, “they are quite frustrated, because the web people are young, and they are a little bit flashy, and they get all the attention all the time, [but] they know so well that their medium is by far much, much bigger than the web.”

So if teletext is still so popular, why does it still look like an Atari game? Quite simply, the technology doesn’t allow any major changes. Bolstad says that in NRK, the code was standardized in the early 1980s, and the standard has stayed the same. The given structure won’t allow for any more pages that there already are (900), or for a sharper image on the text or graphics. In theory, this standard code could be updated, but since everyone at NRK has been waiting for it to die, it hasn’t made sense to put the time or money into an update.

People don’t seem to mind, though. “Teletext has not developed at all for 30 years,” Heikki Lammi, head of YLE online news, writes in an e-mail, acknowledging that teletext is “ugly” in comparison to even the most basic websites. “The concept and layout are just the same as they were in the 1980’s…. Stories are short, only four paragraphs.” And yet, he writes, teletext remains Finland’s most popular news medium—not because it’s pretty, but because it works: “Because in Teletext, content is all that counts.”

Of course, it was only a matter of time before someone made a teletext app for the smartphone. As incongruous as it seems to have 1970s-era technology displayed on a device as fast, sleek, and powerful as an iPhone or a Droid, teletext apps are actually incredibly popular throughout Scandinavia. The public broadcasters don’t produce their own apps, but they release the teletext content as a free datastream, so commercial services like oxorr and others have developed and sold mobile versions.

According to Larsson, SVT’s televised teletext audience had actually been declining slightly for the past several years, but then saw a sharp uptick in 2011. She attributes that, in part, to a new subset of readers who first got in the habit of checking teletext on their smartphones and then started watching it on their TV sets once they got home.

SVT in Sweden recently used its teletext system to marry a very old bit of technology with another very new one: Twitter. A developer created a program that automatically uploaded the tweets of certain Twitter users to the teletext system, and the Tweets then appeared as subtitles on the television. SVT used this method during a big European Idol-esque contest show. It got a mixed reaction. “Parts of the Swedish Twitter-elite didn’t appreciate the project—they argued that this robbed Twitter of its social aspects,” writes Hanna Larsson, head of online news at SVT in an email. “Others thought it enhanced the TV broadcast in a nice way.”

Larsson’s evaluation of the experiment contains a significant point: at the moment, a relatively small number of Scandinavians have signed up for Twitter. Throughout Scandinavia, the percentage of people who have signed up for Facebook is relatively high, but Twitter has not caught on nearly as quickly. For instance, according to Swedish news siteThe Local, about 43 percent of Swedes have Facebook accounts, while only 2 percent are on Twitter.

If and when Twitter takes hold in Scandinavia, it remains to be seen what effect that might have on teletext’s longevity, especially as the older generations of teletext readers—who read exclusively on their television sets—are replaced by smartphone-addicted younger generations. Will they continue to download teletext apps, and appreciate the uncluttered, all-business content that the news outlets put out? Or will younger users prefer the conversational, brightly-colored, and nearly-immediate social network as the go-to place for the news of the moment?

NRK’s Erik Bolstad doesn’t think that social media necessarily replaces teletext, nor does the Internet; each one has its own particular purposes. But he noted in a follow-up e-mail conversation that mobile news apps accessed via smartphone could be starting to replace Teletext for users under 50. “We have a very steep increase in mobile news usage, and a slow decline of Teletext, which seems to be related,” he writes. Teletext was designed to be used for quick, frequent headline-checking, rather than long reads or analysis, he explains, and many mobile news apps have the same function and usage patterns.

Although teletext has survived—even thrived—in Scandinavia for much longer than even its developers could rightfully expect it to, its gradual decline is inevitable. So enjoy its artful simplicity while you can.

Lauren Kirchner is a freelance writer covering digital security for CJR. Find her on Twitter at @lkirchner