Sign up for the daily CJR newsletter.

The number of live videos posted to The New York Times’ main Facebook page has consistently surpassed regular videos in the 12 months since Facebook began paying select media partners to use its nascent streaming platform—yet viewing figures for Facebook Live lag far behind.

The Times is one of about 140 media companies and celebrities the platform giant enticed to produce content for Facebook Live through deals totalling a reported $50 million last year. According to The Wall Street Journal, the 12-month deal signed by the Times was worth $3.03 million, a figure surpassed only by the $3.05 million Facebook paid to BuzzFeed.

Now that it’s been a year, how did the Times adapt its video strategy to accommodate Facebook’s investment? An analysis of every video posted to the Times Facebook page from February 2016 to April 2017 shows fewer views for the live ones, but higher engagement. Ultimately, the cost-benefit equation for publishers distributing video content on social platforms remains unclear.

The first year

Since the Times cross-posted its first Live video in February 2016, a total of 1,417 Live videos have been added to its main Facebook page—considerably more than the 1,244 regular videos posted during the same period. Since the contract is believed to have begun in April 2016, there were only two months—November and December 2016—in which the number of Live videos did not exceed the number of regular ones. The precise number of videos the Times was obligated to post by the terms of its agreement with Facebook is unknown, but from April 2016 to April 2017, it posted an average of 4.4 Live videos per day on weekdays (1.4 of which were cross-posted from other Times accounts), and 1.6 per day at weekends (0.5 cross-posted).

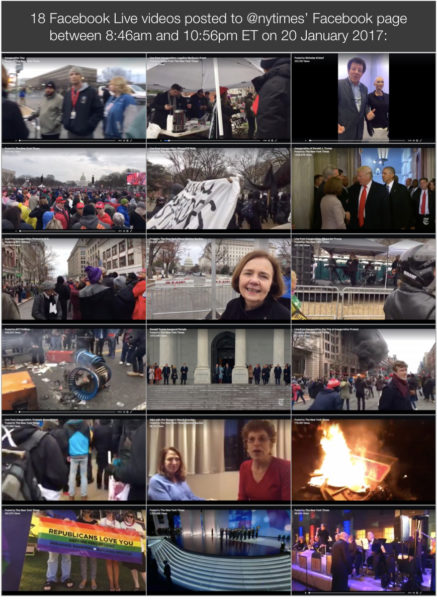

The volume of daily posts has fluctuated considerably. One or more Live videos were posted on 344 of the 395 days between April 1, 2016 and April 30, 2017. There have been seven occasions on which 10 or more Live videos have been posted in a day, with the 18 posted on January 20, 2017, the day of Donald Trump’s inauguration, marking the highest daily peak.

Facebook Live was rolled out to publishers in early 2016 following its launch in August 2015. In March of 2016, Facebook announced it would pay a select group of content creators to produce video for its live platform.

RELATED: Facebook is eating the world

The first Facebook Live video posted to the Times’ page was a live Q&A cross-posted from op-ed columnist Nicholas Kristof’s page in February. The Times posted the first Live video of its own on April 5, a live Q&A with the editor of The New York Times Food and the editor in chief of T: The New York Times Style Magazine.

Given that Facebook paid the Times and others significant sums to create Live videos as part of a broader push for video across the platform, the output bankrolled by the big-money deals struck by Facebook has been subject to close scrutiny. In August 2016, around four months into the Facebook deal, the quality of the Times’ Live output came in for criticism from Times Public Editor Liz Spayd. Spayd opined in “Facebook Live: Too Much, Too Soon”:

Too many don’t live up to the journalistic quality one typically associates with The New York Times… It’s as if we passed over beta and went straight to bulk. What I hope is that The Times pauses to regroup, returning with a rigor that more sharply defines the exceptional and rejects the second-rate. After all, the world has a glut of bad video and not enough of the kind The Times is capable of producing.

The Times’ Live output also lags far behind its standard, non-live videos in terms of views. As of May 1, 2017, the 1,417 Live videos posted to the Times’ main page had accrued a total of around 243 million views (an average of 172,000 per video). During the same period, regular, non-live videos—of which the Times has posted 173 fewer—collected almost 740 million views (an average of 595,000 per video).

Analysis of the most popular videos on the Times’ Facebook page highlights the importance of the 2016 election in driving views of Live output. Of the 10 most viewed Live videos, eight related to the election. These included live broadcasts of the three presidential elections (2nd, 6th, and 9th most viewed), analysis of the presidential race by Times journalists (4th and 5th), Obama’s farewell speech (7th), and Trump’s inauguration and victory speeches (9th and 10th, respectively). With 5.8 million views, the four-hour stream of the Women’s March in January 2017 is the Times’ most watched Live video to date.

RELATED: The Facebook rescue that wasn’t

The 10 most viewed regular videos since April 2016 are far more varied by comparison. Only three captions mention Trump or Clinton, and none reference the election. The most viewed video, a profile of Olympic athlete Simone Biles, has been viewed well over 50 million times. A video exposing the vulgar language used by attendees of Trump rallies has accrued over 23 million.

Live video breeds engagement

The Times told us that “success is often less about numbers, and more about encouraging journalists to embrace a new platform. The most valuable metrics go beyond views: how long people watched a segment, did they share a live segment, did they comment?” Indeed, the metric through which Live videos typically outperform regular ones is comments. According to our data, Live videos accrue an average of 1,011 comments, more than double the average of 536 on regular videos.

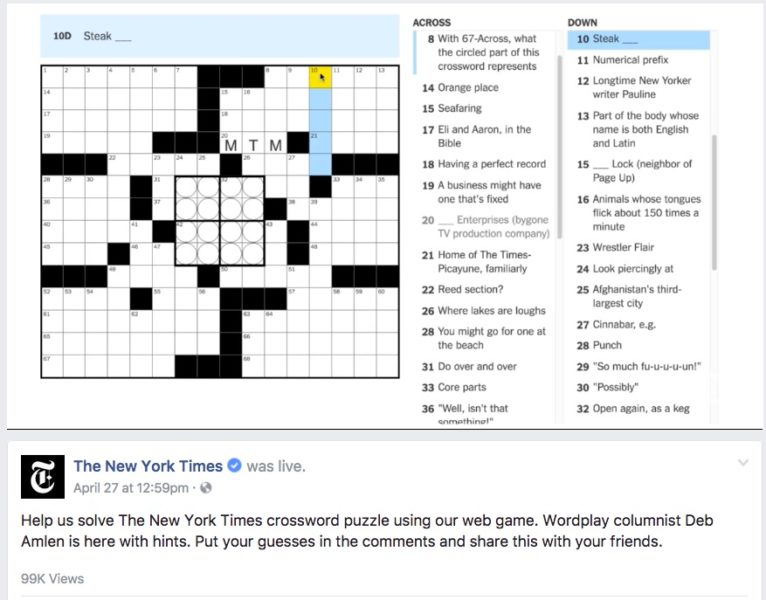

The accompanying captions suggest that soliciting engagement through comments is an active part of the Times’ Live strategy. Fifty-five percent of the Live videos contained explicit calls to action encouraging viewers to leave comments. While these typically take the form of questions for journalists or their interviewee, they have also been used for other purposes, such as crowdsourcing answers to the Times crossword.

The three Live videos with the most comments were the three presidential debates, with the first garnering a whopping 169,057 comments. The other Live video to generate over 50,000 comments came after the Trump campaign circulated a survey about the mainstream media via its email list and the Times invited viewers to comment saying how they would answer the questions.

Is Facebook Live worth it?

The unique selling point for Live is the opportunity to engage with Times journalists over a topical issue in real time, be it a presidential debate or the day’s crossword. This kind of engagement has potential to build bridges between the Times and the enormous Facebook user base and ultimately develop brand loyalty. But it also comes at a cost—with no obvious way of measuring the benefits.

For publishers, weighing up the pros and cons of Facebook Live is far from straightforward. On the plus side, publishers are provided with a ready-made live streaming infrastructure, they have new ways to try and reach Facebook’s vast user base, and their journalists are able to experiment with a new platform and new forms of storytelling. Concurrently, though, publishers have to dedicate expensive resources to creating and moderating videos which are effectively exclusive content for Facebook—they do not control the audience data generated by their output. While they receive (potentially unreliable) data regarding the scale and reach of their videos, and may eventually receive a share of revenue from mid-roll ads, they cannot effectively measure the returns on their investment. In other words, the costs of producing Facebook-exclusive Live videos can be quantified, but the tangible benefits to brand and subscription base cannot.

For Facebook, the benefits of Live appear more clear cut: Following an initial financial outlay, a wide range of publishers continue to deliver vast swathes of exclusive live video to its platform—video that Facebook has not hidden its desire to monetize. For publishers wanting to know if those videos will ever deliver a worthwhile return in their bottom lines, it’s a familiar guessing game.

The first year of Facebook Live epitomizes why social platforms are centerstage in the existential crisis around journalism. Despite the fact publishers are fighting a losing battle for digital advertising revenue, most feel unable to disregard the eye-watering scale social platforms can deliver. In the case of Live, publishers create content that not only directs users to Facebook but keeps them there, further strengthening Facebook’s hand with advertisers—all, presumably, in the hope that they will eventually benefit from a share of the spoils. Yet it remains a relationship premised on potential: the promise of jam tomorrow. For now, the question of whether that potential will ever be realized remains impossible to answer.

ICYMI: A Meryl Streep, Tom Hanks movie has former New York Times journalists pretty ticked off

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.