Sign up for the daily CJR newsletter.

On August 12, 2018, Nina Berman, a photojournalist who covers American political movements and a professor at Columbia University’s Graduate School of Journalism, was photographing the “Unite the Right 2” rally in Washington DC. The rally was organized by one of the leaders of the violent Unite the Right rally in Charlottesville the year before. Berman hoped to see what issues motivated the participants and how the press covered the event.

In a closed-off area, where some ralliers were giving interviews, Berman spotted a couple, a man and a woman, with tattoos down their arms and their faces partially hidden by scarves. She took a picture. She later saw the woman telling a TV reporter that she was protesting what she considered threats to her first amendment rights. When Berman reviewed her photos after the rally, she looked more closely at the tattoos, and a series of numbers on the woman’s forearm caught her eye. They read “1488”—a white supremacist meme. The 14 represents white nationalist idealogue and convicted murderer David Lane’s 14-word slogan, “We must secure the existence of our people and a future for white children,” and the 88 represents “Heil Hitler,” “H” being the 8th letter of the alphabet.

The symbol was new to Berman. She reflected that had she been able to identify this symbol in the moment, she would have asked the woman directly about it.

Berman wanted that problem solved, for herself and for other journalists who would no doubt encounter it. Today, a team comprised of Susan McGregor and myself at the Tow Center for Digital Journalism, Shih-Fu Chang, Svebor Karaman, and Xu Zhang of the Digital Video/Multimedia (DVMM) Lab of the School of Engineering and Applied Science (and supported by the Data Science Institute Center for Data, Media & Society), and Berman herself at Columbia are working to do so. Such symbols are constantly evolving and photographers, journalists, and the public should have a reliable resource to consult in order to understand them.

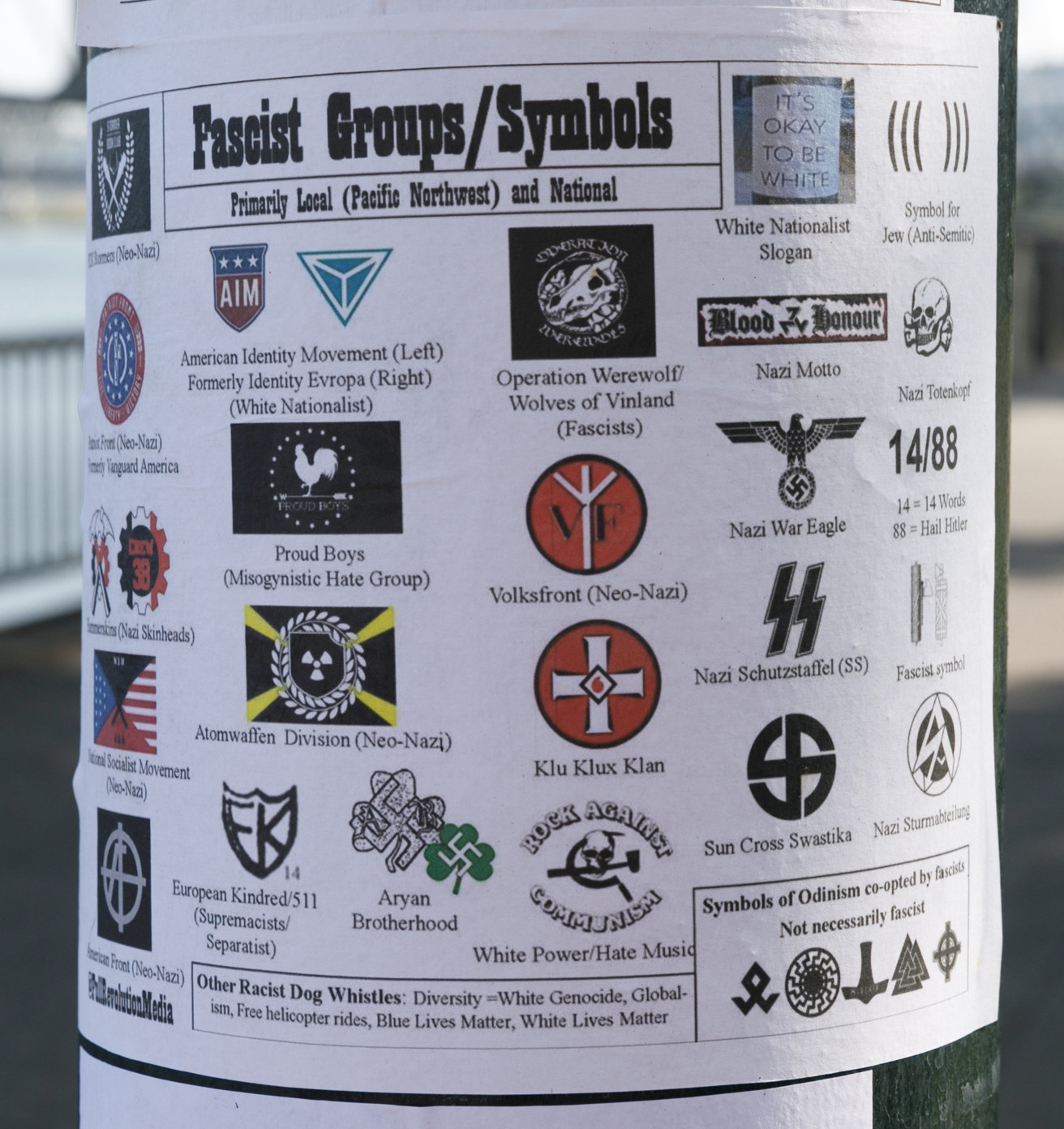

Teachers and researchers aren’t the only ones thinking about the problem of poor visual literacy in political symbols. In the weeks leading up to a right-wing rally in Portland, Oregon on August 17th, activists posted notices to educate the public about symbols that might be displayed on flags, clothing, or tattoos in their city, some on the streets and others on social media.

The images below show some of these notices. The image in the tweet was created by members of “Communities Against Racism Standing Up for Black Lives,” a Facebook group. The “Crash Course in Far-Right Symbols” was written by the American Iron Front, an anti-fascist organization. The “Fascist Groups/Symbols” flyer was made by Full Revolution Media, another leftist Facebook account:

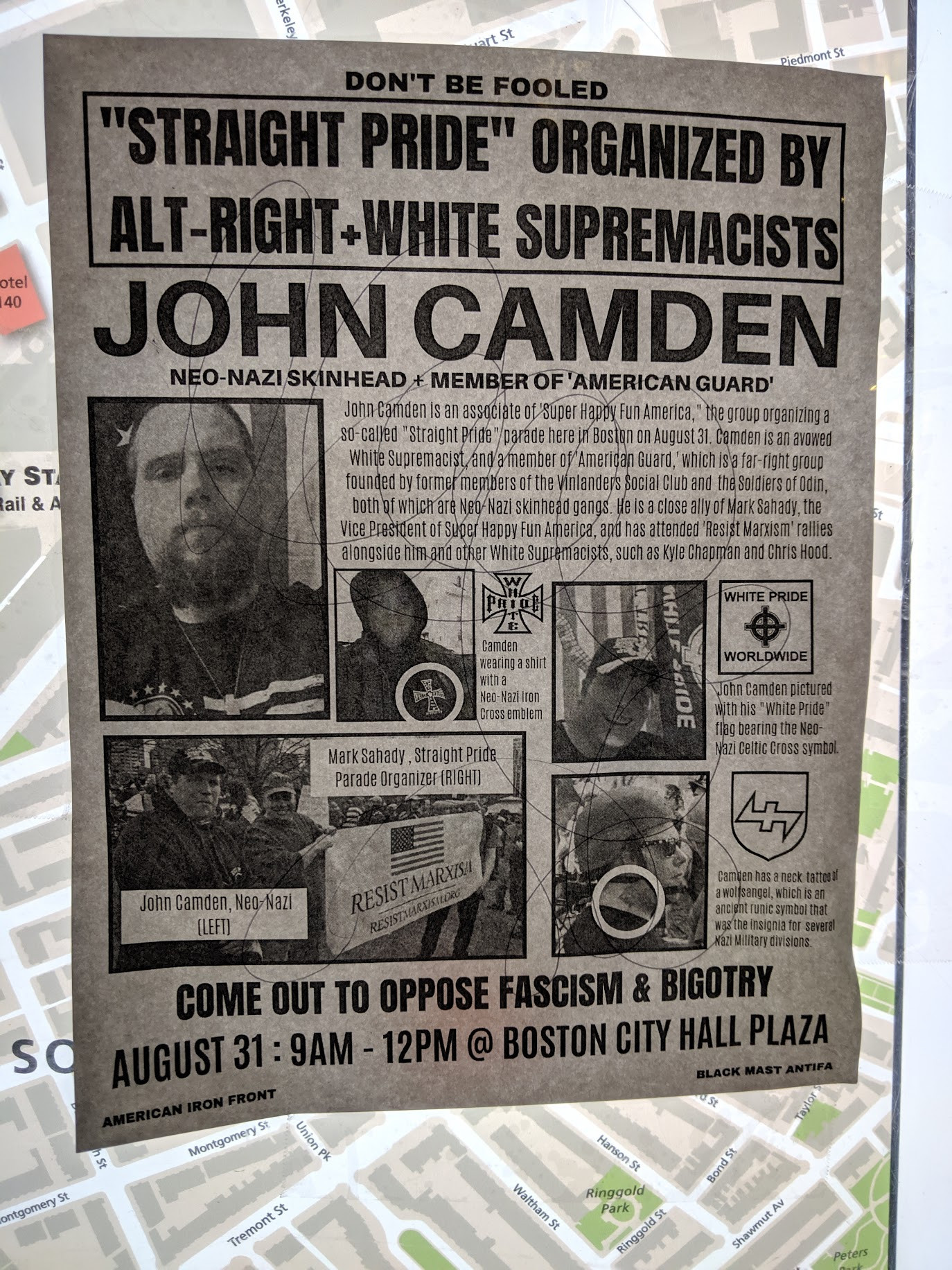

Similar notices from the American Iron Front, Black Mast Antifa and North Shore Antifa appeared in Boston in August, in the days leading up to and after the “Straight Pride Parade.” The authors of the paper notice shown below printed photos of John Camden, the president of a right-wing organization rumored to be attending the parade, in which he wears white supremacist symbols. This warned the public that the parade would be organized and attended by white supremacists. The North Shore Antifa post documents white supremacist symbols present at the parade itself.

Mainstream media outlets have also published guides to symbols used by political groups The Washington Post identified the symbols, flags, and slogans of white nationalist and counterprotester groups (anti-fascist groups have their own iconography) at the Unite the Right march in Charlottesville in August 2017.

These solutions are welcome, but paper signs and websites have limited reach. Instead, what if people could consult a real-time, in-the-moment, query-able resource to learn what a given symbol means? For journalists, such a resource could serve as an invaluable aid to their reporting.

App Design

We are designing an app that will identify political symbols in a photograph that the user uploads, and provide context about those symbols: historical origins, what groups have used the symbol recently, the ideology of these groups, recent news about those groups, and so on. The app is modeled partially on Leafsnap and Merlin Bird ID, which identify species of trees and birds, respectively.

The app will work in real time. Its primary utility is to help the user define unfamiliar symbols, but it might also notice and define symbols that the user hasn’t yet seen in the image. The app can also be a useful backstop for photo editors, so that they avoid publishing a political symbol without intending to. The same goes for anyone uploading an image anywhere on the Internet.

For the app to work, we need to solve two technical problems: first, we need a computational method that can identify known political symbols in a given image. Next, we need a way to track new symbols and new versions of existing symbols so that we can update the app’s database regularly. Thanks in large part to the efforts of the DVMM Lab researchers, we have made considerable progress solving the first of these problems, using state-of-the-art algorithms from the field of computer vision. And none of the progress would have been possible without several hundred example images of political symbols with which we trained the algorithm—Berman herself gave us many images, along with a number of other photographers who cover political rallies.

We will be showcasing our symbol detection tool on September 26th at NYC Media Lab’s Demo Day. After seeking initial feedback, we intend to interview journalists, news photographers, and other professionals to understand what information about symbols they would like the app to give them and how best to design it.

Straight Pride Parade

In an effort to better understand the domain in which this app would most commonly be used— political rallies—some members of the team attended the Straight Pride Parade in Boston as members of the press. We left with three main lessons: i) when asked about the meaning of a symbol they bear, people are not always inclined to give complete or truthful answers, ii) there were many symbols we hadn’t yet encountered, which we take as evidence of the constantly evolving nature of political symbols, and iii) some symbols originate online—where political communities can organize and recruit in closed communities deliberately difficult for journalists to enter and observe—and then spill out into the real world.

We saw many unfamiliar symbols at the Straight Pride parade and were offered incongruous explanations. One rallier had “1488” tattooed on his knuckles, “SS” on his forearm, and a glyph called the Odal Rune on his back:

He told us that these symbols celebrated his “heritage.” As discussed above, 1488 is a white supremacist symbol. The lightning-bolt shaped SS is most likely the SS Bolts symbol, the logo of the Schutzstaffel, a paramilitary force led by Heinrich Himmler that served Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party. The Odal Rune is a symbol from the Germanic Futhark alphabet used by an SS regiment of Germans and ethnic German conscripts that became infamous for its cruelty to civilians during the Second World War.

Both the SS Bolts symbols and the Odal Rune can appear in non-white supremacist/non-neo-Nazi contexts. The ADL states that biker gangs at one time adopted SS bolts as “shock symbols” rather than out of direct malice against Jewish people or other minorities, and Odal Runes appear in fiction and reference books. But here, together with the 1488 symbol, there is a good chance the bearer intended them to be read as white supremacist symbols. His explanation of “heritage” is a different, or at the very least severely incomplete, definition of what we know these symbols to mean.

With our app, reporters will be armed with in-the-moment context about the meaning and history of political symbols, and will be able to push back on such false, incomplete, or deliberately vague answers. The app will also be useful for, reporters who can’t reach or are unwilling to engage the person bearing the symbol.

In the parade we saw some symbols or variants of symbols we hadn’t seen before in our research. There was a black-and-white US flag with a single green stripe. It resembled the “Blue Lives Matter” flag, but with green instead of blue:

According to CRWFlags.com, a non-verified database of flags and their meanings, it “represents Federal Agents such as Border Patrol, Park Rangers, Game Wardens and Conservation Personnel. Some consider the Thin Green Line Flag as representing military as well.”

On the counter-protester side, we saw two variants of the Iron Front symbol that we hadn’t yet encountered. The Iron Front symbol, used by antifascist organizations in the USA today, is derived from a German paramilitary organization in the Weimar Republic that fought the Nazi Party and the Communist Party of Germany.

We had not seen these particular colors in this symbol before.

We also came across a few runic-looking symbols we had never seen before:

Because they appeared in the context of the rally, we plan to research these symbols further. The man with the elbow tattoo told us it meant “chaos.” It is likely that the symbol also has a more overtly political meaning, because this symbol for chaos is often used in alt-right lore (although the symbol itself originates in fantasy literature). These symbols suggest that in some cases, symbols related by root to known symbols might be of interest to users of our app. Furthermore, sometimes it is only when several symbols appear together that we can begin to discern their political message. This is something to consider for the future of our app.

Some political symbols at the parade originated online as memes and then spilled out into the real world. One rallygoer, for instance, sported a “Kekistan” flag on his t-shirt:

“Free Kekistan” shirt

When asked what the flag meant to him, he told us the satirical story of “Kekistan,” a country whose “peaceful farmers were just tending to their memes,” but faced a government that wanted to take the memes away through political correctness. Once again, his answer omitted context for people unfamiliar with the symbol—the reference is now often used by white nationalists. The Kekistan flag is essentially the Nazi battle flag in green instead of red, with the logo of 4chan, the internet message board once popular among the alt-right, in place of the Iron Cross on the top left.

We saw another man wearing what looked like a “Pepe the Frog” pin. According to the Anti-Defamation League, the Pepe the Frog character first circulated nonpolitically, as a meme with a variety of meanings. But members of the alt-right appropriated Pepe around 2015. Although non-bigoted uses of Pepe still exist—notably in ongoing protests against the Chinese government in Hong Kong—they are outnumbered in the English-speaking world by overtly bigoted uses.

This man told us, though, that the character was not in fact Pepe, but “Honkler the Clown.” He said he discovered Honkler on 4chan and 8chan, and that, Honkler represents the chaos in the world.

In February 2019, racist and anti-Semitic variations of Honkler began appearing on 4chan’s /pol/ imageboard. The character is also associated with the term “honk pill,” an absurdist alternative to “black pill” nihilism emphasizing humor in an absurd universe. It is a veiled reference to Hitler, in keeping with the longstanding tradition among racists of adopting harmless-sounding words as stand-ins for ethnic slurs or other expressions of hate. Neo-Nazis on imageboards, in lieu of saying “Heil Hitler,” often sign off with “Honk Honkler.”

Tracking the evolution of online visual memes and political symbols is essential to the success of our app. One of our goals is that our app will be able to recognize political symbols that are in use online before they have been photographed in the real world.

The intersection of internet culture and politics has caused considerable consternation to journalists seeking to accurately and dispassionately analyze current events. Too often, reporters lose promising stories down rabbit holes of symbology and the matryoshka dolls of ever-smaller and more disparate groups that are nevertheless affecting the course of world events. We hope that we can build a tool that will help to mitigate the time and emotional cost of this reporting.

I will address ethical concerns that have emerged over the course of our work in future writing. So far, we are pleased with the positive reception we have received from the news photographers who have discussed the project with us. We hope to receive constructive feedback from patrons of NYC Media Lab’s Demo Day today, September 26th at New York City College of Technology (CUNY), 285 Jay Street, Brooklyn, NY 11221 where we will demonstrate our progress so far.

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.