Sign up for the daily CJR newsletter.

In March 2021, Lara Trump posted an interview with her father-in-law to Facebook.

The former president, then suspended from the major platforms, wasted no time repeating unsubstantiated claims about the 2020 election results being illegitimate.

“It was a third-world country voting system,” he said, and referred to the election as “a hoax.”

Facebook removed the video, explaining in an email that anything “in the voice of President Trump” was banned from the platform following the insurrection at the US Capitol two months earlier. To sidestep the ban, Lara Trump used a tactic popular with election deniers: she posted the interview to Rumble, the controversial video platform, before sharing the link on her Facebook page.

Rumble was a perfect fit for Trump’s video. Having positioned itself as a champion of “free speech,” the platform has become a key vector through which baseless claims of election fraud have continued to thrive unabated.

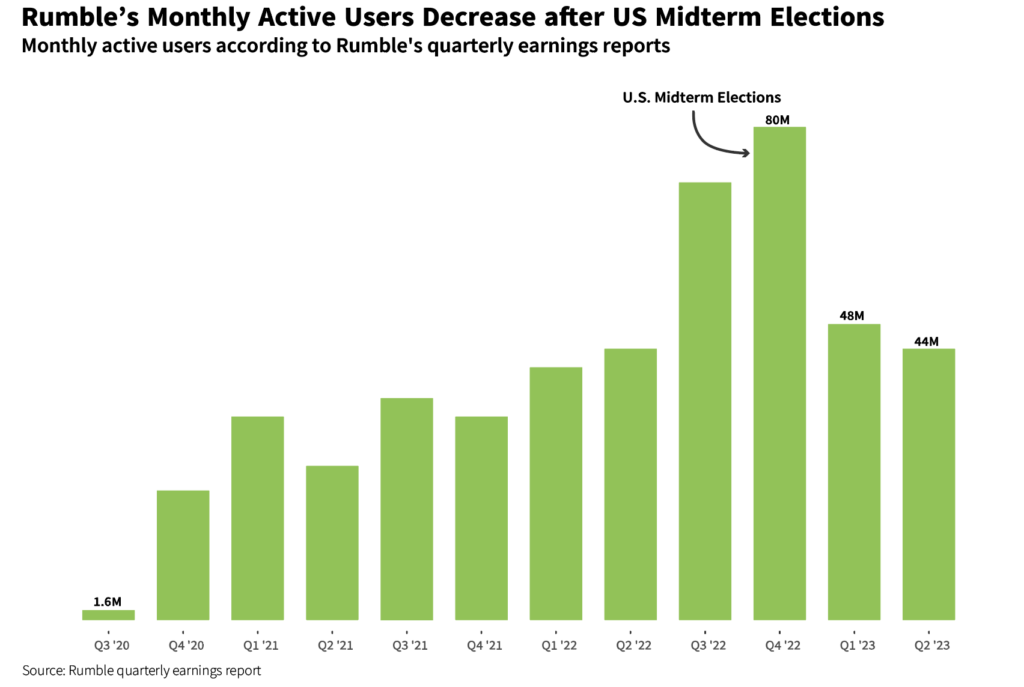

As the U.S. hurtles towards another election cycle, Rumble continues to give a megaphone to false information, although this time with a significantly larger audience. The platform’s viewership numbers have grown from 1.6 million in the third quarter of 2020 to 44 million today, according to its latest quarterly public disclosures. Now, in an effort to broaden its user base, the platform is seeking to look beyond politics and branch out into areas like gaming and sports. It’s a move that risks exposing unsuspecting new users to mis- and disinformation and other inflammatory content lurking in the platform’s murkier corners.

“Rumble is not just a leader in political content, but will now also lead in culture,” chief executive Chris Palovski announced during an earnings conference call earlier this year.

Palovksi, a Canadian who founded the company in 2013, has said that he did not intend to make a platform that favors right-wing content. Rumble is for “the right, the left, and everyone in between,” he recently tweeted. And yet, roughly three-quarters of people who get their news from Rumble identify as Republican or lean towards the Republican party, according to Pew Research. So do its major donors: libertarian investor Peter Thiel and GOP senator JD Vance. Just this June, David Sacks, the Republican donor and Silicon Valley entrepreneur, joined Rumble’s board of directors.

With more cultural content, Palovski aims to reduce the platform’s dependence on political news cycles and elections. During the first three months of 2023, Rumble saw a 40 percent drop in monthly active users, which Palovksi attributed to the platform’s overperformance around the 2022 midterm elections. Now, the platform is recruiting cultural celebrities from other platforms, many of which have been banned or faced content moderation policies elsewhere.

Some of the biggest names include popular Youtube gaming streamer IShowSpeed and Twitch streamer Kai Cenat, who have announced a joint livestream show on Rumble. YouTube hip-hop commentator, DJ Akademiks, also live-streams exclusively on the platform. All three stars have faced bans on mainstream platforms: IShowSpeed was banned from the Amazon-owned Twitch in 2021 after making suggestive remarks to a female TikTok personality during a live stream. And in February, YouTube banned him for “spam or deceptive practices.” DJ Akademiks and Kai Cenat, one of the most popular Twitch streamers, have similarly been banned numerous times for violating Twitch’s community guidelines. “I feel like if I get banned one more time, I’m off the fuckin’ platform for good,” Cenat said during a broadcast a few weeks prior to signing with Rumble.

It’s become a pattern: people with turbulent relationships with mainstream platforms migrate to alternative sites like Rumble. According to a Pew Research report, about a quarter of Rumble’s two-hundred most prominent accounts are banned or demonetized elsewhere. Andrew Tate, a former kickboxer charged with rape, human trafficking and forming an organized crime group to sexually exploit women in Romania, joined the lineup last year after being banned by Instagram, TikTok, YouTube and Facebook for breaching rules on harmful content. When IShowSpeed and Kai Cenat joined Rumble, Tate was quick to tweet his approval and vision for what’s to come: “The largest YouTubers and Twitch streamers in the world have joined Rumble, along with hundreds of others prepared to tell the TRUTH.”

Mizkif, a popular YouTube and Twitch streamer, suggested during a live stream that Rumble is trying to pivot away from its political reputation by recruiting new cultural stars. “Yeah, Rumble is politically driven. True. But, I feel like they’re trying to change with Kai. Obviously. And Speed,” he said.

Mizkif later joined Rumble on a non-exclusive contract, explaining that he wanted to help make the platform more gaming-oriented. “I am doing zero political things over here,” he added.

To attract a younger audience, Rumble has also created a space for itself in the action sports category. In March, the video platform got exclusive streaming rights to two major action sports series: Nitro Rallycross and Street League Skateboarding. They’ve partnered with Power Slap, a slap-fighting organization, which will have its own exclusive show. In a public statement, the partnership was described as a “strategic investment” to grow and diversify Rumble’s content library.

Rumble’s lenient approach to content moderation has allowed for QAnon conspiracy theories, anti-LGBTQ rhetoric, and misogynistic content to grow on the platform. As unsuspecting new users navigate the site for IShowSpeed’s latest livestream, one potential ramification is that they may navigate out of Rumble’s cultural sector and into rabbit holes of extreme content. According to Luke Munn, a research fellow at Digital Cultures & Societies of the University of Queensland, Rumble risks functioning as a radicalization pipeline for a widening audience.

Rumble’s front page is “edgy” and “controversial,” he said, but not necessarily hate speech. However, the content increases in intensity as the users navigate off the front page and start digging into comments, thereby leading the user towards more extreme content. “I call these alt-tech platforms the friendly face of hate because they’re very accessible and intuitive,” he said. “But they also remove a lot of the safeguards which foster extremist, radical, racist, sexist, xenophobic content.”

Last year, Rumble proposed an open-sourced moderation policy that removed an existing ban on material promoting hate groups. Robert Barnes, one of Alex Jones’ defamation attorneys and frequent guest on Infowars, was hired to help draft the policy alongside Canadian lawyer David Freiheit. According to the Daily Beast, Barnes stripped language from the current content moderation policy that specifically bans material supporting and promoting groups such as the Ku Klux Klan and white supremacist groups. “Barnes’ proposed terms not only do away with naming those groups, but they don’t say anything about content promoting hate groups at all,” the review states.

Rumble has defined itself against the big tech platforms by offering an experience free of ‘censorship.’ While big tech companies are not liable for the content published on their platforms due to Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act, they began moderating more aggressively after coming under fire in 2016 and 2020. (Although, in recent months, many of these measures have slipped away). Still, the difference between Rumble and YouTube’s respective approaches to moderation can attract a certain kind of users to the former.

According to Sander van der Linden, a professor of social psychology at the University of Cambridge who studies misinformation, people come to free-speech platforms like Rumble because they see it as one of the last havens for unmoderated speech. “The psychological lure is very much that people want to be in the know,” he said. “They want to be part of the truth seekers.”

But with the influx of new cultural content to Rumble, new users who aren’t necessarily “truth seekers” may nonetheless stumble across the misinformation and extreme content that’s hosted on the platform.

In fact, it can be almost difficult to avoid. A Media Matters investigation found Rumble currently hosts a QAnon-affiliated show called Why We Vote that amplifies election misinformation and conspiracy theories. The channel behind it, Badlands Media, has appeared on Rumble’s leaderboard at least 225 times since the beginning of February, according to Media Matters data. Likewise, an investigation by Wired revealed that Rumble actively recommends misinformation. “If you search ‘vaccine’ on Rumble, you are three times more likely to be recommended videos containing misinformation about the coronavirus than accurate information.” A quick search for ‘2020 election’ on Rumble reveals that nearly every top suggested video makes claims about the election being fraudulent or illegitimate (Rumble’s press team did not return Tow’s request for comment).

A search for ‘2020 election’ on Rumble reveals that nearly every top-suggested video makes claims about the election being fraudulent or illegitimate

While mainstream platforms still have problematic content on their site, van der Linden said, they are at least attempting to avoid explicitly recommending it. Rumble, by contrast, is putting conspiracy theories directly on its front page.

“At least when you’re in an echo chamber on Twitter, or Facebook, or YouTube, there is a potential to get back to mainstream news,” van der Linden said. “But on these platforms, that’s all you get.”

Concerns about Rumble 2.0’s potential to cause harm seem unlikely to dampen the platform’s ambitions. During an interview earlier this year, Palovski made his ambitions clear: “There’s this moment in time where everyone is really dissatisfied with the current incumbent platforms,” he said. “And we are going to strike.”

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.