Sign up for the daily CJR newsletter.

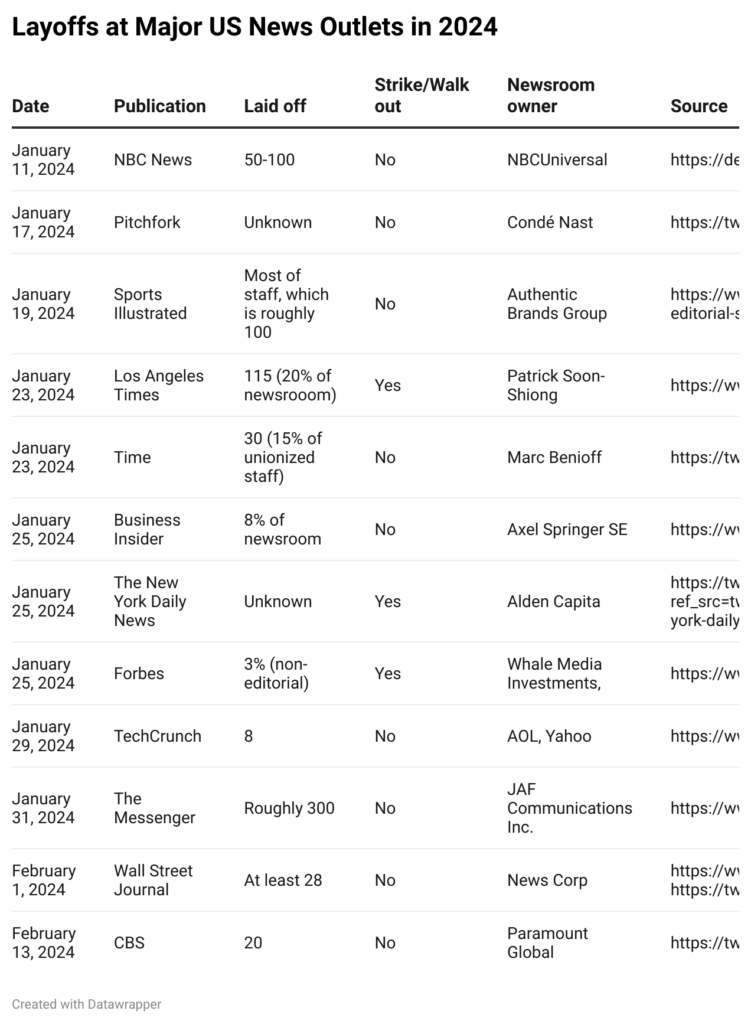

The US news industry didn’t catch a break in the new year. Over five hundred news workers were laid off in January, according to an employment tracker report. This figure doesn’t include the three hundred journalists cut from The Messenger less than a year after its launch. Bleak headlines have dubbed the past months a “Journalism Bloodbath,” and some suggest the news industry is facing a possible media extinction. These events escalate amid an election cycle, triggering concerns about the media’s upcoming political coverage.

It’s an old story by now that local news in the US is struggling. But as the past month has starkly demonstrated, many of the factors hurting local newsrooms are catching up to national outlets as well. The first six weeks of the year have brought layoffs at some of the biggest publications, including NBC News, Sports Illustrated, Business Insider, and Time. The Los Angeles Times cut over a hundred reporters—roughly 20 percent of its newsroom. The music publication Pitchfork reportedly laid off over half of its employees when Condé Nast folded the outlet into GQ. Anna Wintour, Condé’s chief content officer, notoriously delivered the news to employees without removing her signature sunglasses. The cuts struck into the capital as well. As Cameron Joseph reported for CJR last week, the Wall Street Journal amputated a big chunk of its Washington bureau, axing nearly half of its journalists.

X, formerly Twitter, is flooded with posts from recently unemployed journalists seeking new career opportunities. The three hundred journalists laid off from The Messenger received neither severance nor healthcare, leading several ex-employees to start a GoFundMe page. “Working through this traumatic incident over the past few days has been challenging,” reads a statement from the page. “It’s been even more stressful knowing that many of us don’t have a safety net for support while we look for a new job.”

These layoffs follow the worst year for the news industry since the pandemic. According to one report, 2023 had over twenty-five hundred layoffs in broadcast, print, and digital news media. Perhaps most memorably, BuzzFeed News closed, and the Washington Post offered buyouts to two hundred and forty employees. It’s not necessarily that the demand for news is lower; according to one recent Columbia study, consumption of news content remains robust. But the absence of an equally robust business model continues to suck the oxygen out of news organizations.

Publications that used to rely on advertisements now have to compete with tech giants. The Columbia report argued that Google and Meta should pay news outlets $14 billion annually in revenue for their search traffic and content. As technology companies incorporate AI-enhanced search experiences, which create answers to the user’s question in the sidebar, some fear that users will opt for these short answers. This would further damage the news business model: news consumed on platforms means no traffic to news sites, which means no ad revenue, no brand affiliation, and no chance to convert paying subscribers.

Tow spoke with Victor Pickard, a professor at the University of Pennsylvania’s Annenberg School for Communication, about the underlying cause of these layoffs and ways to rethink our media systems. According to Pickard, the recent layoffs are a continuation of what has been a downhill trend for journalism in the past decade. Indeed, startling numbers from a 2023 report by the Medill School of Journalism showed that since 2005, the newspaper industry has lost nearly two-thirds of its journalists and nearly a third of its newspapers. The current downturn highlights the need for a structural fix to the failing commercial model, Pickard said. This includes systematic alternatives such as nonprofit (examples include ProPublica and the Texas Tribune) and public-ownership models. “We’re seeing a grimmer confirmation of a trend that we’re already painfully well aware of, which is, there really is no market solution,” Pickard said.

Some publications, like the New York Times and The New Yorker, have successfully implemented a subscription-based model. But few local and nonurban newspapers have found success with this approach. Also, according to Pickard, paywalls risk creating greater inequality among those with access to quality local news. “People who are willing to pay tend to be from wealthier and whiter households,” he said. “So if we’re gonna go with this model, we’re automatically disenfranchising millions of Americans from having access to local news to public service journalism.”

The decline of newspapers has led to news deserts, which disproportionately hurt people of color, rural districts, and people of lower socioeconomic status. The situation creates an information vacuum that attracts misinformation, clickbait content, and hyperpartisan pseudo-journalism. In an attempt to deal with the news crisis, publications have looked to billionaires like Patrick Soon-Shiong (owner of the LA Times), Jeff Bezos (owner of the Washington Post), and Marc Benioff (owner of Time). However, as reported by the New York Times, these media companies lost millions of dollars last year despite big investments. Billionaires, it turns out, can’t erase many of the underlying factors hurting journalism. This has become especially apparent in light of the recent layoffs at the LA Times and Time magazine.

There’s a need for a media system that allows all members of society to have access to a baseline level of news and information. However, this requires significant modes of public funding. Examples of government-funded newsrooms include NPR, BBC (UK), and CBC (Canada). But as of 2020, federal funding of US public media reached about $1.40 per capita—a tiny number compared with that of other democratic countries (many Northern European countries devote around $100). According to Pickard, democracy requires a new long-term vision that untangles news and capital. “We should think of journalism, not as a commodity whose worth is determined by its profitability in the market, but as a public service,” he said.

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.