Sign up for the daily CJR newsletter.

The popular and opaque social media app WeChat has been largely overlooked as a culprit in spreading misinformation during and after the 2016 election season. Anti-Hillary memes and conspiracy theories about sharia law found their way onto the mobile messaging platform, which serves the growing number of Chinese immigrants in the United States.

With 889 million monthly active users, WeChat has more than triple the user base of Snapchat and half that of Facebook. It is the social media platform of choice in mainland China, used for everything from social networking and messaging to takeout orders and personal finance. In the US, it emerged as a primary avenue for pro-Trump sentiments and mobilization, especially for first-generation Chinese immigrants. Partisan news outlets native to WeChat sprung up during the 2016 election, and continue to this day. They still actively stoke right-wing sentiment, with recent headlines such as “Liberal media threatens to violently destroy Mount Rushmore,” “George Soros backed the violence in Charlottesville,” and “Illegal Immigrant Started Wildfire in Sonoma County.”

ICYMI: Some WSJ staffers are probably unhappy right now

Like the English media world, WeChat is characterized by a dazzling array of content generators and the potential for polarization. A huge number of organizations post to WeChat, but there is little to no information available identifying the influential players—the Politicos and the Breitbarts of the platform. With support from the Tow Center for Digital Journalism, my team at the University of Southern California is collaborating with The Alhambra Source and Asian American Advancing Justice to assess the nature of bias and misinformation in WeChat and ethnic Chinese media and to explore strategies for intervention.

With features reminiscent of WhatsApp, Facebook, and Twitter, WeChat combines the intimacy of mobile messaging and small-group interactions with the capacity for viral dissemination. But WeChat is notoriously opaque. This hybrid platform provides no API, which restricts analysis of its content and user behavior. This is not uncommon: Weibo, the microblogging site whose popularity was eclipsed by Wechat, restricted its API a few years ago. For these companies, data is not only something to be monetized, but also coveted information ultimately under control of Chinese authorities.

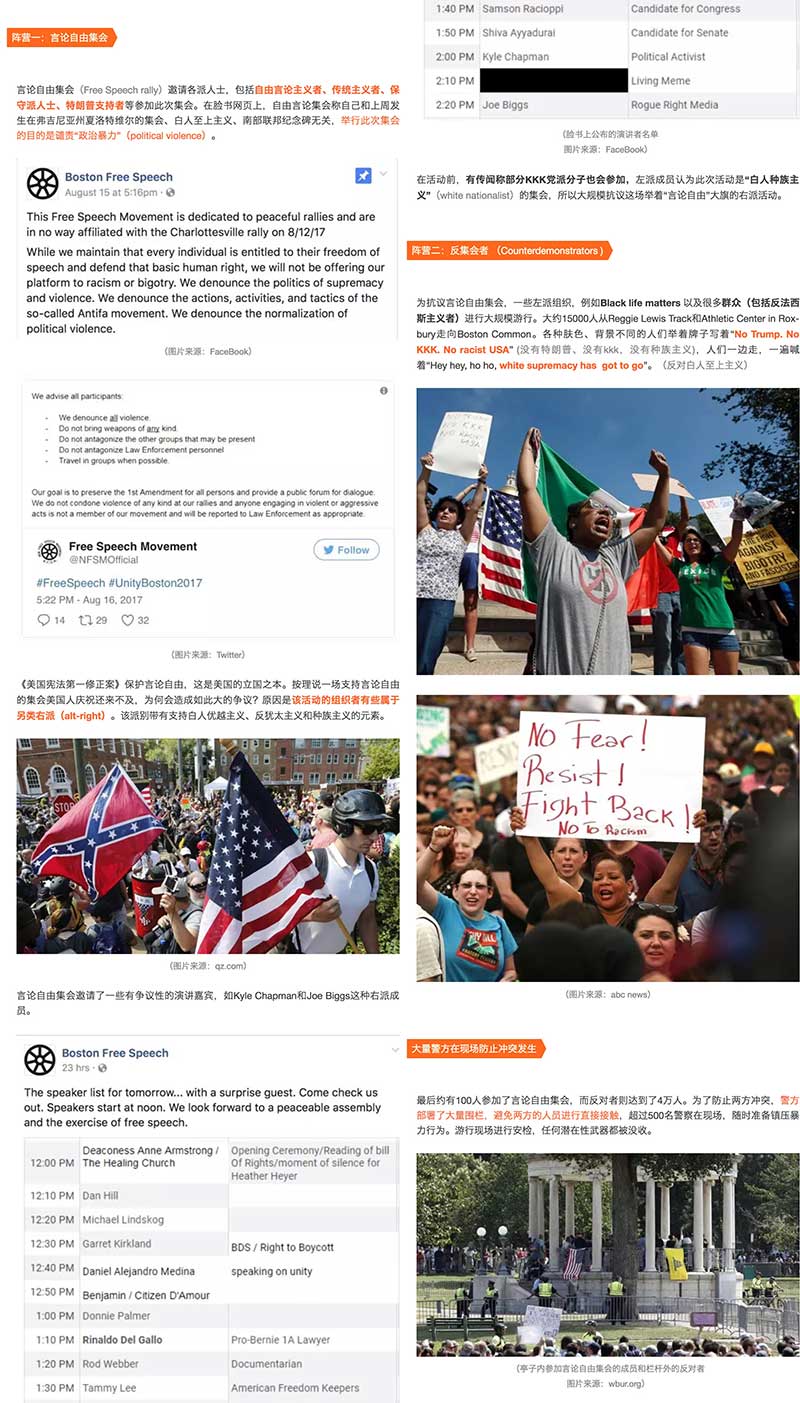

Many information outlets, known as Official Accounts (OAs), are native to WeChat. OAs are in-platform, content-based accounts that anyone can start, and they vary greatly in their activity level and size of operation. Think of NowThis, or political blogs that only exist within a social platform rather than on the open web. News content on OAs can be original but are often repackaged from other media sources. For example, in the screenshot to the right, the article covering the recent “free speech” rally in Boston sourced from venues such as ABC, Facebook, and WBUR, Boston’s local NPR station.

By the last official count in April 2017, there were 10 million OAs in WeChat. There is a low barrier to entry, and becoming an OA grants access to the vast user base to focus on niche audiences. Most metropolitan areas in the US with an established immigrant Chinese population have their own OAs specializing in local news and consumer information. Some draw a decidedly pro-Trump crowd.

ICYMI: “It’s a story that I think can potentially save people’s lives”

Unlike Twitter and Facebook, WeChat does not have hashtags or trending topics. OAs generate and dispatch content to their subscribers, and subsequent dissemination happens when users share content within chat groups and Moments, WeChat’s news feed–like feature. These are private or semi-private networks. Chat groups range from smaller, more intimate groups formed with family members, friends, and colleagues, to groups organized around common interest, issue, or locality, where membership is subject to approval by the administrator. What you share on Moments can only be seen by your friends; there is no option to make posts publicly visible.

All discussion about the news content takes place within the bounds of private and semi-private networks. Information cascades through networks of friends and acquaintances, rather than across a (theoretically) open, connected public sphere. Users cannot reply to or tag OA accounts, or others who are not part of her existing network. Although some OAs enable reader comments, which comments get displayed are entirely at the discretion of the OA.

Content on WeChat is also primarily curated by the individual user and his or her social network. This means that WeChat cannot effectively tweak platform design to prevent the spread of misinformation or the presence of filter bubbles. While Facebook might alter its algorithm to bring more varied content to users, such changes are not applicable to WeChat. Neither are bots a problem on WeChat.

Official attempts at containing fake news on WeChat could easily slip into the territory of censorship. WeChat has long invested in efforts to detect and remove “fake news,” including a feature for users to report false information and tools that automatically detect keywords to remove associated content. However, within the purview of WeChat’s fake news filter are not only banal rumors such as “padded bras cause cancer,” but also politically undesirable content.

Given the lack of API access and private nature of the platform design, we know how many times an article has been viewed, and that is about it. WeChat does not even reveal follower numbers to anyone besides the owners of OAs. More insightful questions about network structure and information flow—who has viewed the article and through what pathways the article ended up traveling—cannot be grasped by computational tools.

Traditional methods such as user surveys and digital ethnography could be key to piercing the veil of WeChat’s news ecosystem and lending clues to potential intervention strategies. This is why we are partnering with local media and organizations that have strong ties with the community to explore the issue and formulate solutions together. The case of WeChat also reminds us that when it comes confronting the reality of social media and spread of fake news, there is no one-size-fits-all solution, and that strategies need not always be high tech.

ICYMI: For Facebook, the political reckoning has begun

Correction: This piece has been updated to reflect the fact that in May 2017 WeChat introduced a search function.

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.