Executive Summary

Today, journalists are facing increased threats in the world. As New York Times publisher A.G. Sulzberger stated in his May 2023 speech before UNESCO for World Press Freedom Day, “All over the world, independent journalists and press freedoms are under attack.”1 A.G. Sulzberger, 2023 World Press Freedom Day Keynote Address. (May 2, 2023), https://www.nytco.com/press/2023-world-press-freedom-day-keynote-address/ But what this statement fails to capture is that journalists’ work is under threat not just abroad, in dangerous parts of the world, but within the United States on a daily basis in much less visible ways. American journalists are increasingly prevented from accessing the information they need to hold the powerful to account. As Daniel Ellsberg said in an April 2023 investigative journalism conference in California, there has to be more reporting on our country’s systems of secrecy. This paper looks at some of the ways corporate secrecy has been leveraged against reporters seeking to tell the full story.

One system of increasing secrecy involves corporate actors holding space for more of our lives that now take place online. While this trend has led to an increase in data creation, it has also led to more walls being erected, thwarting access to information that was previously public. Since the pandemic, week-long conferences, investor calls, and court hearings that were all once held in person often now take place online. Although the ease of this information sharing can be a cause for celebration, this bounty of data is increasingly kept locked away. Through new legal and technological measures, private actors can more easily stop public access to growing troves of data. Such techniques create deleterious new barriers for journalists, academics, and policymakers tasked with reporting on powerful entities that shape all aspects of public life. Without access to this information, society becomes at risk of being unable to verify the truth, at the same time that artificial intelligence makes the proliferation of false information easier than ever.2At the same time that this opacity continues, “authorities and society at large have been pursuing increased transparency and disclosure,” to combat various social harms that can occur without greater awareness or knowledge. Anneka Randhaw, Jonah Anderson, & Laura Higgins, Four major changes to corporate transparency in 2022. WHITE & CASE (Mar. 30, 2022), https://www.whitecase.com/insight-alert/four-major-changes-corporate-transparency-2022.

This paper hopes to reveal how corporate control over information has been used to legally stymie access to data in the United States, at the same time that our lives online have created more data than ever before. This paper will excavate five specific ways through which corporate actions have thwarted public transparency, including (1) the rise of company towns withholding electronic data; (2) legal threats made under the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act (CFAA) and state laws; (3) the growth and manipulation of trade secrecy law and confidential business information exemptions; (4) the increasing passage of Congressional laws blocking corporate transparency; and (5) the recent Supreme Court decisions stymieing the possibility for state transparency laws alongside the ballooning incidence of shell companies used to withhold crucial financial information from the public.

To look deeper at these issues, this paper uses various case studies, including several from the author’s own legal practice as the general counsel of The Center for Investigative Reporting (CIR), the oldest nonprofit newsroom in the country. In her role as general counsel, the author has assisted and defended reporters working on various investigations and observed how reporters have increasingly been thwarted from doing their jobs by having corporations block access to data, often online. The author delves into these case studies and the surrounding body of law to explain how newsrooms face increased challenges in obtaining information held by at least in part by private companies.

The five key findings of this paper:

- Companies are creating private towns that control the same number if not more responsibilities as local governments, but unlike local governments, demand contractual secrecy from local governments that bar disclosure under local public records acts.

- Moving live events to online spaces has left reporters more susceptible to being excluded from access to information under the CFAA as well as other state laws.

- Since 2019 there has been an expansion in trade secrecy law and confidential business information exceptions which permit for the withholding information that previously would have been public.

- In the past decade Congress has passed various statutes that require data secrecy and circumvent general public-access laws.

- In the last five years the Supreme Court has issued two decisions that make it more difficult for states to pass transparency laws. At the same time, there has been a rise in shell companies over the past quarter century which permit anonymity in a way that corrupts various finance sectors (such as real estate and public health) undermining a healthy marketplace.

In conclusion, while this paper is not a holistic map of corporate secrecy — nor does it come close to encapsulating all the transparency needs in the United States — it is the beginning of a study that demands further observation, i.e. how our existence on the Internet is creating more opacity in our society. At the same time as more of our democratic landscape is led and controlled by actors online, more transparency is needed than ever.

Overview

A 2020 survey of dozens of investigative journalists working on financial crime and corruption in 41 countries asked respondents to name the main source of threats against them. Seventy-one percent of respondents identified3 Susan Coughtrie & Poppy Ogier, Unsafe for Scrutiny: Examining the pressures faced by journalists uncovering financial crime and corruption around the world. THE FOREIGN POLICY CENTRE (Nov. 2020), https://fpc.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/Unsafe-for-Scrutiny-November-2020.pdf. This was followed by organized crime groups and the government, jointly, at 51 percent. threats from corporations as more ubiquitous than threats from other entities like organized crime groups or governments. Similar recent reports by UNESCO and the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ) showed that repression tactics used to prevent journalists around the world from doing critical reporting4 UNESCO, Journalism is a public good: World trends in freedom of expression and media development. Paris, 2022. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000380618 have started to include not only violent physical attacks but also informational attacks conducted by corporate actors on reporters, such as legal threats against reporters or stymieing access to information.5 Id. at 93, 96. (Both state and nonstate actors use these tactics to gain access to confidential information and intimidate journalists.) The United States is no outlier to this trend. Various aspects of newsgathering online for U.S. reporters have been thwarted by corporate actors more often than in decades before when these avenues were not available, especially as our lives have gone almost ubiquitously online since the beginning of the COVID pandemic.

This paper aims to provide a review of five ways private actors have manipulated the law to obfuscate information from journalists and create more opacity:

- the control of government functions through the growth of company towns;

- the rise of potential claims under the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act (CFAA) and other statutes as more events take place online in the post-COVID era;

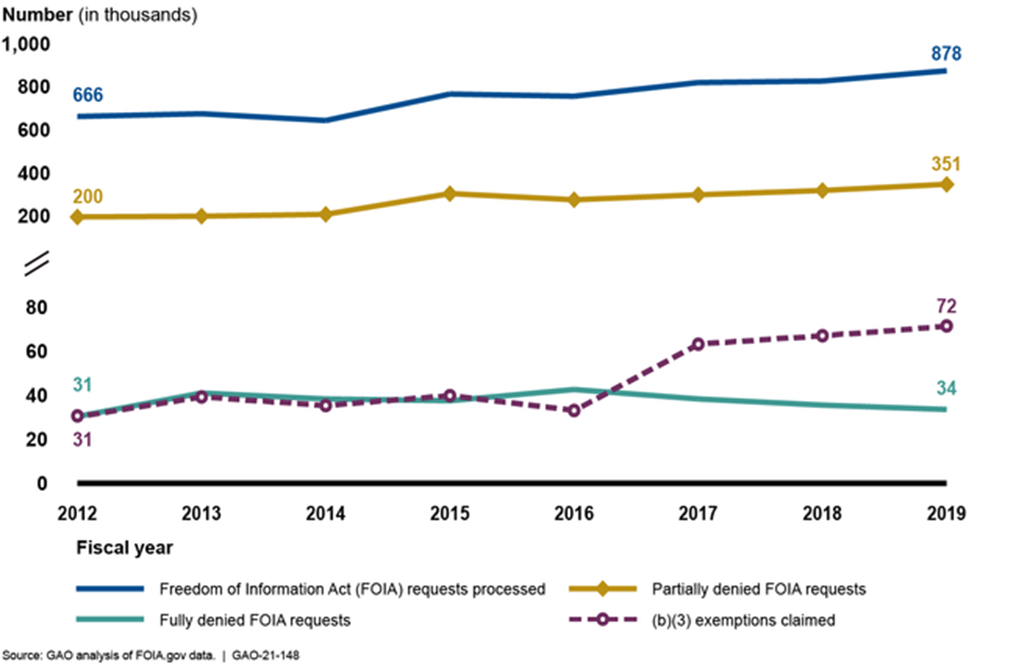

- the expansion of trade secrecy and “confidential business information” exemptions under the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA);

- the passage of new laws to override FOIA’s presumption of openness; and

- two recent Supreme Court rulings that make the state transparency laws more difficult to pass at the same time that shell companies are frequently used to obfuscate unfair dealings.

These problems listed above are all exacerbated by the fact that an increasing number of government tasks have been delegated to private contractors. The privatization of the federal government’s public functions is no secret. For instance, just looking at America’s penal system, the number of individuals housed in private prisons since 2000 has increased 14 percent.6 Mackenzie Buday & Ashley Nellis, Private Prisons in the United States. THE SENTENCING PROJECT (Aug. 23, 2022), https://www.sentencingproject.org/reports/private-prisons-in-the-united-states/ Indeed, “the largest prison system relying on privatization is the federal Bureau of Prisons (BOP), which has increased its reliance on private facilities by 79 percent since 2000.”7 Id. (Starting in 2021, President Biden signed an executive order to phase out private prisons used by BOP.)

With this shift of responsibility to the private sector, public information concerning even our most vulnerable populations is now swiftly being passed from government to private entities. By handing off such information to contractors, the government can defer questions of access to corporate actors who eschew responsibility and are not held accountable to the public.

Many of the examples used to display this growing opacity are taken from the reporting at The Center for Investigative Reporting (aka CIR or Reveal, its radio program and podcast), where the author is employed as general counsel. Increasingly, the cases tackled by CIR’s newsroom show that as private actors are contracted to do more government work, and as more of the Internet becomes an active place of growth (particularly since the COVID pandemic began), more public information is being withheld from Americans. This paper aims to show how and where those changes have taken place, and to inspire possible solutions for change.

Corporate actors creating company towns

In recent years, corporations have built company towns around the United States through which they are able to act as pseudo-governors. In creating these towns, they contract with governing bodies like state or local townships and impose obligations for government officials to withhold public information,8Caroline O’Donovan, When Cities Sign Secret Contracts With Big Tech Companies, Citizens Suffer. BUZZFEED NEWS (Nov. 20, 2018), https://www.buzzfeednews.com/article/carolineodonovan/amazon-hq2-google-foxconn-secret-nda-real-estate-deals. including from journalists, often in contravention of local public records laws.9Matt Drange, ‘A gag order for life’ — How nondisclosure agreements silence and control workers in Silicon Valley. BUSINESS INSIDER (July 27, 2021), https://www.businessinsider.com/how-nondisclosure-agreements-silence-control-workers-silicon-valley-2021-7. Many employees are similarly gagged from speaking about these agreements.10Id. As a journalist for Business Insider reported, one such contract explicitly required “Employee may state only ‘I can’t discuss it’ or ‘I would prefer not to discuss the matter.’”11Matt Drange (@mattdrange). TWITTER (July 27, 2021, 4:50 PM), https://twitter.com/mattdrange/status/1420049048027860998. This secrecy is acutely problematic where companies are in control of every aspect of towns, including municipal technologies that can violate citizens’ privacy and other rights.

A. Background on Company Towns and Legal Precedent

In the early twentieth century, United States corporations often built company towns designed “as both social and physical” spaces that included “centers with social and community facilities and … numerous parks, playgrounds, and other recreational amenities.”12 Margaret Crawford, The “New” Company Town. 30 PERSPECTA 48, 49 (1999), https://doi.org/10.2307/1567228 In doing so, they “hoped that appealing and well-designed communities would build loyalty and stability and thus head off more strikes.”13Id Over the first few decades of the twentieth century, more than 40 new industrial towns were created.14Id However, “[b]y the end of the 1920s, the new company town was all but dead,” being viewed as “outdated” and engaging in “excessive paternalism.”15 Id. at 55. These towns of the 1920s, however, sparked a major question of debate in the country that continues to reverberate today: When a company takes on responsibilities generally assigned to the government, who is accountable to the public — and what must the company disclose?16Id. at 51.

That question is more alive than ever as more government functions are ascribed to private companies, and as corporations like Google and Facebook17Also referred to as Alphabet and Meta. seek to acquire entire towns under their ownership, as was done in the late nineteenth century. This widespread growth of company control revives the dilemma of whether corporations can be held responsible in the same way that local governments are held accountable to the public.

The first attempt to answer this question came from a case originating from Chickasaw, Alabama, a company town that was the subject of the 1946 Supreme Court case Marsh v. Alabama. Chickasaw was owned by Gulf Shipbuilding Corporation, which controlled the streets, sidewalks, and stores.18Molly Shaffer Van Houweling, Sidewalks, Sewers, and State Action in Cyberspace. THE BERKMAN KLEIN CENTER FOR INTERNET & SOCIETY (2000), https://cyber.harvard.edu/is02/readings/stateaction-shaffer-van-houweling.html. In 1945, when Grace Marsh, a Jehovah’s Witness, entered Chickasaw and started passing out leaflets, she was arrested for trespassing and distributing literature on Gulf Shipbuilding’s property. Signs around town identified the town as “private property” where “solicitation of any kind” was off-limits.19Id.

Marsh sued the town as a government actor that was responsible for censoring her speech under the First Amendment. When the case came before the Supreme Court, the main question was whether the town could be sued as a state actor under the “state action doctrine,” a rule that holds that the First Amendment and all other constitutional protections apply exclusively to the government. Under the state action doctrine, private actors are not prohibited from limiting a citizen’s rights. Applying this rule to itself as a shield, Gulf Shipbuilding Corporation claimed that the state action doctrine barred a ruling against it because they were a private company.

In Marsh, the Court decided, for the first time, in an unique but narrow ruling that a corporation could be held liable under the state-action doctrine. The Court held that because a company-owned town was akin to a normal government-owned town, Gulf Shipbuilding Corporation had to be treated like a normal government that would be held accountable for censoring speech. The Court found that the private ownership of Chickasaw was a mere technicality that could not let the company circumvent responsibility that other government-run towns faced. In essence, when the company looked, smelled, and acted like a government-owned town, it was one. Justice Hugo L. Black’s opinion, writing for the Court, stated that “many people” live in “company-owned towns,” and these towns “must make decisions which affect the welfare of community and nation.”20Marsh v. Alabama, 326 U.S. 501, 508 (1946) (stating signs identified the town as “private property” where “solicitation of any kind” was off-limits).

B. The Rise of Modern Company Towns

Today, various corporate towns around the world are considering these exact questions: Who is responsible in a company town, for what, and what must they disclose to the public?

In 2017, a twelve-acre plot of land in Toronto became a subject of hot debate when a “provincial not-for-profit corporation,”21 Ellen P. Goodman & Julia Powles, Urbanism Under Google: Lessons from Sidewalk Toronto. FORDHAM L. REV. 88 (2) 457, 458-60 (2019), https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/flr/vol88/iss2/4. Waterfront Toronto (WT), decided to join Sidewalk Labs LLC, a self-proclaimed “urban innovation firm” owned by Google, to develop the land into a modern “urban development” that would be a “testbed for emerging technologies, materials and processes.”22 Id. To bring the project to fruition, the LLC signed an agreement (the “Sidewalk Toronto agreement”) with the city to define the parameters of the development. The Sidewalk Toronto agreement was harshly criticized as the town intended to overstep citizens’ privacy rights, and the agreement would gravely stymie individuals’ access to information about the project, perfectly demonstrating the danger in corporate control over traditional government functions.

Complaints about the Toronto project ultimately centered on two key issues involving the collection of data from private citizens: how the company’s collection of data infringed on privacy and the strict secrecy around the held information.23 Id. at 466-68 From the outset, activists and the press complained that the plan for the project was itself shrouded in secrecy. In fact, the initial agreement between WT and Sidewalk Labs was not released in full: “[T]he parties contracted to keep the full twenty-nine-page agreement confidential, sharing it with government staff only in a limited fashion.”24Id. at 464. The Framework Agreement was only released to the public on the day it was replaced by the Plan Development Agreement. Id. at 469-70. To make matters more opaque, it included references to other agreements to which the public had not received access.25Id. WT’s constitution further exempted its records from FOIA requests, so it did not need to disclose its agreements unless it chose to do so.26 Id. City residents subsequently “expressed concerns about data, secrecy, scope, the corporate role in planning, and the absence of public accountability.”27 Id. at 466.

Additionally concerns grew around the privacy violations involved with the data collection. The Sidewalk Toronto project was meant to create a “digital layer” of infrastructure where data would become “the foundation for all downstream production of goods and service.”28 Id. at 476, 478. This layer would include the set of data, sensors, cameras, data storage, and wireless and wired infrastructure, among other “things data touches.”29 Id. at 476. Through this arrangement, the urban governance would track any person that enters the city and “facilitat[e] the collection and transmission of data to applications and services that run on top of the platform” of the city.30 Id. at 479. In other words, the data of any tracked person would be shared freely with the company. While the agreement referenced “general and vague principles” of data privacy, it did not include any specific information31 Id. at 466-67. and while the project stated it would create a “Privacy by Design” policy,32 Id. at 467. one of the key people hired to develop it resigned after the project failed to meet its promises regarding de-identifying data.33 Id. at 474. By keeping key details secret about the project, these and other privacy concerns were more easily able to be withheld from the public.

By turning over public governance to a private platform, the Sidewalk Toronto project was completely kept free from public accountability. “Whoever controls the ‘digital layer’ of the city exerts control over the activities transacted through it.”34 Id. at 479. Such privatization would largely exclude the public from contributing to the direction of the development, and from regulation and enforcement matters. For instance, Sidewalk, rather than a traditional public zoning body, would determine factors like land use.35 Id. at 480-82. Thus, by having Sidewalk in control, it would most likely be “optimized for efficiency and the efficient production of material value, which would serve the private interest rather than the public.” 36 Id. at 487.

While the Sidewalk Toronto project has been canceled, the problems that came with it are far from over. Throughout the United States, several companies and organizations have begun or proposed taking over their surrounding towns and developing them as company-run communities. This section describes efforts by Facebook, Google, and Blockchains LLC to develop these types of programs.

While the Sidewalk Toronto project has been canceled, the problems that came with it are far from over.37Daniel L. Doctoroff, Why we’re no longer pursuing the Quayside project — and what’s next for Sidewalk Labs. MEDIUM (May 7, 2020), https://medium.com/sidewalk-talk/why-were-no-longer-pursuing-the-quayside-project-and-what-s-next-for-sidewalk-labs-9a61de3fee3a. (The Sidewalk CEO attributed the decision to end the project to “unprecedented economic uncertainty” that “set in around the world and in the Toronto real estate market” due to COVID-19.) See also Andrew J. Hawkins, Alphabet’s Sidewalk Labs Shuts Down Toronto Smart City Project. THE VERGE (May 7, 2020) (stating Waterfront Toronto indicated it did not contribute to the decision to end the project), https://www.theverge.com/2020/5/7/21250594/alphabet-sidewalk-labs-toronto-quayside-shutting-down Throughout the United States, several companies and organizations have begun or proposed taking over their surrounding towns and developing them as company-run communities. This section describes efforts by Facebook, Google, and Blockchains LLC to develop these types of programs.

1. Google

Google has taken various steps to expand its presence within and outside of its Silicon Valley community. In September 2020, Google announced its newest proposed community, Middlefield Park, which would include about 1.3 million square feet of offices and six residential buildings comprising 1,675 to 1,850 residences.38Kevin Forestieri, Google unveils massive mixed-use housing and office village in East Whisman. MOUNTAIN VIEW VOICE (Sept. 1, 2020), https://www.mv-voice.com/news/2020/09/01/google-unveils-massive-mixed-use-housing-and-office-village-in-east-whisman. The plan additionally called for retail, restaurant, and community/civic spaces, along with parkland and a private utility system.39See City of Mountain View, Google Middlefield Park Master Plan, https://www.mountainview.gov/depts/comdev/planning/activeprojects/google/middlefieldpark.asp, accessed Jan. 10, 2023. In July 2021, Google hosted public meetings to receive input on its plan.40 Id.

In addition to this new plan, Google in 2019 formally applied to build a second headquarters in San Jose, which would include up to 7.3 million square feet of office space, up to 5,900 units of housing, and 15 acres of park and green space.41Jennifer Elias, Google expands plans for its massive second headquarters in San Jose. CNBC (Oct. 11, 2019), https://www.cnbc.com/2019/10/11/google-expands-plans-for-second-hq-in-san-jose.html. It would further include hotel rooms and retail and “cultural” spaces.42 Id. Since much of the housing would likely be for Google employees, one article describes the campus as “a next-generation company town”43Veena Dubal, Google as a landlord? A looming feudal nightmare. THE GUARDIAN (July 11, 2019), https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2019/jul/11/google-as-a-landlord-a-looming-feudal-nightmare. where Google will function as the residents’ “employer and landlord — and also the creator, owner and disseminator of their data.”44 Id. By relegating ownership over data to the private company managing the community, Google’s plan in San Jose resembles its sister company’s effort in Toronto.

This San Jose expansion was the subject of local controversy and litigation because of Google’s furtive nature in pursuing the project. Google “made extensive use of nondisclosure agreements in negotiations for its planned second campus in San Jose.”45Elizabeth Dwoskin, Google reaped millions in tax breaks as it secretly expanded its real estate footprint across the U.S. THE WASHINGTON POST (Feb. 15, 2019), https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/economy/google-reaped-millions-of-tax-breaks-as-it-secretly-expanded-its-real-estate-footprint-across-the-us/2019/02/15/7912e10e-3136-11e9-813a-0ab2f17e305b_story.html. This secrecy at early stages of the development process resembles the issues that arose with Sidewalk Toronto. To combat this problem, the First Amendment Coalition, a public interest organization committed to freedom of speech, filed a lawsuit with other public interest groups in 2018 against the City of San Jose under the California Public Records Act. The plaintiffs sought records about the new Google campus and any nondisclosure agreements (NDAs) signed by city officials.46The First Amendment Coalition (FAC), FAC And Local Community Group Sue San Jose Over Secret Negotiations With Google (Nov. 13, 2018), https://firstamendmentcoalition.org/2018/11/fac-and-local-community-group-sue-san-jose-over-secret-negotiations-with-google/. While the judge dismissed the complaint, the city did release thousands of pages of documents. See Janice Bitters, Judge sides with San Jose on transparency lawsuit over Google negotiations, SAN JOSE SPOTLIGHT (Aug. 20, 2019), https://sanjosespotlight.com/judge-sides-with-san-jose-on-transparency-lawsuit-over-google-negotiations/. They also separately alleged violations of the Brown Act, California’s law requiring open meetings.47 Id.

Beyond the development of new spaces in California, Google has continued to deliberately withhold information as it expands elsewhere with new offices and data centers. Its “development spree has often been shrouded in secrecy, making it nearly impossible for some communities to know, let alone protest or debate, who is using their land, their resources, and their tax dollars until after the fact.”48 Dwoskin, supra note 44. For instance, Google has required public officials in eight cities to sign NDAs during its real estate transactions, and has further used shell companies to conceal its identity in transactions in Iowa, Tennessee, and North Carolina, among other locations.49 Id. Google’s identity would only be revealed at a later point in the process when there would no longer be public debate over its deals.50 Id. Moreover, the North Carolina city of Lenoir “agreed to treat as a trade secret information about [Google’s] energy and water use, the number of workers to be employed by the data center, and the amount of capital the company would invest”; Google’s subsidiary then pushed to make those trade secrets exempt from disclosure under public records requests.51 Id.

2. Facebook

As Facebook has expanded its physical location, it has moved to take over and control public services in its neighborhood, slowly leaking into the role of governor. In these arrangements Facebook has often employed NDAs, as it has customarily done with its employees in other circumstances.52Michelle Dean, Contracts of Silence. COLUMBIA JOURNALISM REVIEW (Winter 2018), https://www.cjr.org/special_report/nda-agreement.php. NDAs are used even in the most seemingly innocent settings involving land. For instance, Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg required NDAs from farmers and small-business owners he met when he toured the United States in 2017.53 Id.

Since 2013, Facebook has funded many government-like services, including a police substation in the Belle Haven neighborhood of Menlo Park near Facebook’s main campus.54Sarah Emerson, How Facebook Bought a Police Force. VICE (Oct. 23, 2019), https://www.vice.com/en/article/d3akm7/how-facebook-bought-a-police-force In 2014, it granted $600,000 to the city to fund the hiring of a community safety officer for up to five years at the substation, which at the time may have been the only privately funded full-time policing role in the country.55 Id. Critics feared the possibility of preferential treatment.56Id. Meanwhile, beginning in 2016, Facebook sought to fund a new unit of the Menlo Park Police Department to service the area around its campuses. When the city council considered the issue in 2017, it negotiated a deal with Facebook for the unit to be funded by a “general in-lieu sales tax agreement” for $11.2 million to be paid to Menlo Park’s “unrestricted general fund.” Under the arrangement, Facebook would not technically be paying directly for the police unit, and the city would not be under a legal obligation to use the money for the police force. The unit was fully staffed by August 2019.

But even more concretely, Facebook is developing its plans for the creation of Willow Village, a retail, recreational, residential, and professional community in Menlo Park.57See David Streitfeld, Welcome to Zucktown. Where Everything Is Just Zucky. NEW YORK TIMES (Mar. 21, 2018), https://www.nytimes.com/2018/03/21/technology/facebook-zucktown-willow-village.html. The community would include “1,729 housing units, 1.25 million square feet of office space, a 193-room hotel, shopping space, including a grocery store, as well as a publicly accessible neighborhood park, elevated park area, dog park, and town square.”58 Kate Bradshaw, Facebook’s Willow Village now includes giant glass dome, “High Line” path and more. PALO ALTO ONLINE (Jan. 12, 2021), https://www.paloaltoonline.com/news/2021/01/12/facebooks-willow-village-now-includes-giant-glass-dome-high-line-path-and-more. This development is designed to emphasize public spaces, replacing industrial warehouses and office buildings with “a town square and main street where the business, housing and ground-floor retail areas would connect.”59 Id. Facebook would not manage the retail stores but would own the property.60Streitfeld, supra note 56.

Willow Village shares some similarities and differences with the Sidewalk Toronto project. This project, like Sidewalk Toronto, demonstrates an attempt by a major technology company to create an urban environment under its control. Just as Sidewalk Labs would have likely controlled much of users’ data from the area, Facebook would own and operate the physical area under its geographic control.61 Unlike Sidewalk Labs, reports have not indicated that Facebook would manage the data of those in the Willow Village community.

To the extent that Facebook as a private entity fulfills responsibilities traditionally performed by a city, and has enough power to shape the actions of the city, the Willow Village project could succumb to the same concerns of privatization and secrecy as the Sidewalk Toronto project did. One local advocate explained that “Corporations are paying for things that the city or county and state used to pay for,” and noted that the corporations have more money and more power than the city — leaving them especially vulnerable to abusing those powers when governing with no checks and balances.62Id. Bradshaw, supra note 57. Nevertheless, the process of developing Willow Village seems at least somewhat more responsive to public engagement than the Sidewalk Toronto project. While Sidewalk Toronto obscured its plans from public view, Facebook has modified its plans in response to public feedback. For example, it expanded the number of housing units and lessened the size of office space following concerns about the region’s traffic and “already high ratio of jobs to housing units.”

3. Blockchains

Blockchains LLC, a fledgling cryptocurrency company based in Nevada, developed a proposal to create a city driven by blockchain technology.63Sam Metz, Nevada governor wants lawmakers to study ‘Innovation Zones.’ ASSOCIATED PRESS (Apr. 26, 2021), https://apnews.com/article/local-governments-technology-business-government-and-politics-nevada-e3bd9ef669145af228adcfaadcf7cdb1. Jeffrey Berns, the founder of Blockchains, purchased 67,000 acres of land in Storey County, Nevada, which he sought to develop into a “smart city.”64Joshua Nevett, Nevada smart city: A millionaire’s plan to create a local government. BBC (Mar. 18, 2021), https://www.bbc.com/news/world-us-canada-56409924. Under his vision, the city would ultimately house more than 36,000 residents who would rely on blockchain-supported apps to access city services.65 Id.

To create this city, Blockchains called for Nevada to establish “innovation zones”66It stated, “Any private sector applicant pursuing emerging technologies such as blockchain, autonomous vehicles, and artificial intelligence would be allowed to develop a mixed-use community, so long as it clears minimum investment and greenfield land requirements.” See Laura Bliss, In Nevada, A Utopian Vision Gets a Blockchain Twist. BLOOMBERG CITYLAB (Mar. 9, 2021), https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2021-03-09/nevada-asks-can-blockchain-build-a-smarter-city. where companies could assume local governance powers and pursue blockchain innovations. Early language even “proposed allowing three county commission-like board members — two of whom would be from the company itself — to create court systems, impose taxes, build infrastructure and make land and water management decisions.”67Metz, supra note 62. While the new city would include traditional utility services, like water and power, the group had not yet determined how that infrastructure would be operated.68 Bliss, supra note 65.

Nevada Governor Steve Sisolak initially endorsed the plan, saying it would diversify the state’s economy and make it a “hub for cryptocurrency.”69 Id. See also Metz, supra note 62. But local leaders in Storey County voted in March 2021 against supporting the “separatist” government on the Blockchains-owned land.70 Nevett, supra note 63.

Other skeptics pointed to concerns about the democratic implications for turning over land to a company to develop into a municipality, and referenced the Sidewalk Toronto project as a “cautionary tale[]” after it “was abandoned last year after fierce opposition from privacy advocates and financial pressures.”71 Id. Sisolak later called instead for a committee to study the “innovation zones” to make an informed opinion on the opportunity.72 Metz, supra note 62.

The Nevada proposal, which was ultimately withdrawn,73Sam Metz, Tech company asks to withdraw ‘Innovation Zones’ plan for Northern Nevada. ASSOCIATED PRESS (Oct. 7, 2021), https://www.rgj.com/story/news/politics/2021/10/07/blockchains-withdraws-innovation-zone-plan-northern-nevada/6046332001/. presented a unique parallel to the Sidewalk Toronto plan. Like that proposal, the Blockchains plan would seemingly transform city operations into a series of data-driven transactions. While the use of blockchain technology would theoretically mean “residents would control their own data with their devices, with their digital identity” rather than rely on “middlemen,”74 Nevett, supra note 63. the proposal still required private entities to assume power, which would implicate the same privatization considerations. Governor Sisolak emphasized that the innovation zones would need to comply with the open meetings and ethics laws that govern traditional cities, but it is unclear from the proposal whether public information would be restricted.75 Bliss, supra note 72.

C. Legal Transparency Obligations of Company Towns

Some might wonder what company towns have to do with newsgathering, but today, as company towns begin to percolate around the United States, the concern over press access and corporate accountability in these towns is higher than ever. The case of Marsh v. Alabama is particularly relevant in this context, as it enlivens the question of whether and when private entities taking on government roles also take on public responsibility and must speak to the press and grant them privileges.

Applying the rule of Marsh, many scholars have argued that companies should be responsible to the public and the press. This argument is even more heightened, as courts around the country have issued differing rulings on whether social media companies can be regulated without offending the First Amendment.76 In 2022, a national debate was spurred over whether legislatures can regulate social media companies and implement certain requirements under the First Amendment. For instance, the Fifth Circuit decision Netchoice v. Paxton, ridiculed on the Techdirt podcast as “the single dumbest court ruling” ever seen, upheld a Texas law regulating social media companies. This stands in contrast with an Eleventh Circuit decision ruled in May 2022 that held similar provisions in a Florida law were unconstitutional as they violated the companies’ First Amendment rights. While most First Amendment and media attorneys disagreed with the Fifth Circuit ruling, many also agree that there must be some accountability and restrictions placed on the outsized power of these companies. See Mike Masnick, 5th Circuit Rewrites A Century Of 1st Amendment Law To Argue Internet Companies Have No Right To Moderate. TECHDIRT, at 4:43 (Sept. 16, 2022), https://www.techdirt.com/2022/09/16/5th-circuit-rewrites-a-century-of-1st-amendment-law-to-argue-internet-companies-have-no-right-to-moderate/; Genevieve Lakier, The Non-First Amendment Law of Freedom of Speech. 134 HARV. L. REV. 2320-24 (2021), https://harvardlawreview.org/2021/05/the-non-first-amendment-law-of-freedom-of-speech/; Press Statement, Knight Institute, Knight Institute Asks Federal Court to Strike Down Florida’s Social Media Law (Nov. 16, 2021), https://knightcolumbia.org/content/knight-institute-asks-federal-court-to-strike-down-floridas-social-media-law-but-urges-court-to-reject-arguments-that-would-prevent-government-from-regulating-to-protect-free-speech-online; Charlie Werzel, Is This the Beginning of the End of the Internet? THE ATLANTIC (Sep. 28, 2022), https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2022/09/netchoice-paxton-first-amendment-social-media-content-moderation/671574/. This paper poses one separate but related question: Could government transparency requirements also apply to a private company taking over municipal responsibilities?

Further supporting this position is a more recent case, Moss v. University of Notre Dame Du Lac.77Moss v. University of Notre Dame Du Lac, 130 HARV. L. REV. 1768, (2017), https://harvardlawreview.org/2017/04/moss-v-university-of-notre-dame-du-lac/. Like Marsh, it involves a First Amendment challenge against a private actor, albeit a private university rather than a corporate town.

In Moss, several individuals committed a racist act against members of an African American student group. Moss, a school administrator, spoke out against the incident and claimed that the school had retaliated against him by denying him a promotion and threatening to terminate his employment, in abrogation of the First Amendment.78 Id. at 1768-69. Once the case reached federal court, Moss argued that “Notre Dame is a state actor like the company town in Marsh” and therefore owed him various protections, unlike a private institution that has fewer obligations as to who or how it fires a person.79 Id. at 1769.

The district court in Indiana denied Notre Dame’s motion to dismiss the complaint, and “rejected the University’s argument that Marsh cannot apply to private universities.”80Id. at 1768-69. The judge considered that the university could possibly be a company town because “‘Notre Dame’s campus is … open to the public and … similar to a traditional town, containing public roads, stores, restaurants, a post office, [and] a police department,’ as well as a fire department, a health center, the state’s second-largest tourist attraction, ‘and more.’”81 Id. at 1770 (quoting Moss, 2016 WL 5394493, at *1, *4).

Moss, which was ultimately settled,82 Moss v. Notre Dame, No. 3:13CV1239-PPS, Order (D. N. Ind. 2017). This case is now closed. may expand what responsibilities can trigger the state action doctrine under Marsh. In essence, where private companies begin — like Notre Dame, Gulf Shipping Company, or Google — to take on more responsibilities of a government actor, it is more likely a court would require them to be publicly accountable, like a governor. In such instances, can the press seek access to records, apply for press passes, and demand more information from private companies in a way they can from their state counterparts? As argued in a recent article in the Harvard Law Review, Moss shows that Marsh could be applied more broadly by not just focusing on municipal services offered by the company.83 Moss v. University of Notre Dame Du Lac, supra note 76, at 1771. Instead, a more “holistic appraisal of the way a place looks and functions from the point-of-view of its inhabitants and visitors” should be considered.84 Id.

Moss describes how Notre Dame houses 6,000 students, maintains an open campus, employs a police force, contains streets that connect with nearby municipalities, and hosts sporting events that are open to tens of thousands of members of the public.85 Id. at 1770-71. Thus, Moss asks whether “the privately-owned place is visually and experientially indistinguishable from a typical municipality and its public sphere.”86 Id. at 1772.

As Silicon Valley companies continue to expand into company towns, media lawyers representing reporters may consider whether First Amendment obligations are triggered under a more holistic application of Marsh demanding more accountability to the public and press.87 Id. at 1775. “Notre Dame provides sewer, water, and power utilities; it has parks. Visitors can stay at Notre Dame’s hotel, enjoy its museum and performing arts center, and catch up on local happenings in the newspaper. These facts reflect much of the substance of municipal life, and they, along with evidence that would show how people interact with the space, may or may not add up to a company town. Judge Moody’s opinion seems to operate on this holistic, experience-oriented view. As Moss and similar cases move forward, courts would do well to expand beyond a “company town” inquiry focused solely on service provision. In order to do so, they can go back to the origins of this branch of the state action doctrine to find that appearance and experience matter.”

Under this theory, attorneys might argue that transparency is a key obligation in our democracy and under the First Amendment. While the First Amendment does not currently require constitutional transparency in America, unlike most countries around the world, this might be a change to codify.88 Article 19 of the United Nations’ Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) states: “Everyone has the right to freedom of opinion and expression; this right includes freedom to … seek, receive and impart information.” Universal Declaration of Human Rights (10 Dec. 1948), U.N.G.A. Res. 217 A (III) (1948), https://www.un.org/en/about-us/universal-declaration-of-human-rights. Article 19 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), ratified by 173 countries, recognizes “the right to seek, receive, and impart information” as one of the three core tenets inherent to human dignity. International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (New York, 16 Dec. 1966) 999 U.N.T.S. 171 and 1057 U.N.T.S. 407, entered into force 23 Mar. 1976, https://www.ohchr.org/sites/default/files/Documents/ProfessionalInterest/ccpr.pdf This author and other academics have argued for this kind of constitutional transparency.89D. Victoria Baranetsky, Keeping the New Governors Accountable: Expanding the First Amendment Right of Access to Silicon Valley. KNIGHT FIRST AMENDMENT INSTITUTE AT COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY (Aug. 21, 2019), https://knightcolumbia.org/content/keeping-the-new-governors-accountable-expanding-the-first-amendment-right-of-access-to-silicon-valley. Under that set of principles, companies would be obligated to disclose public records,90 Some states have already begun instituting provisions demanding corporate transparency, such as California’s California Privacy Rights Act and California Consumer Privacy Act, which more recently included advanced transparency requirements akin to California’s Public Records Act, which requires disclosure of government records. See CPPA Issues Its First Draft of CPRA Regulations. AKIN GUMP (July 11, 2022), https://www.akingump.com/en/news-insights/cppa-issues-its-first-draft-of-cpra-regulations.html. just as the government is required to under various freedom of information acts.

Increased numbers of online meetings cut off from access because of CFAA and other legal concerns

Since the start of the Covid-19 pandemic in 2020, our lives have increasingly taken place online. In tandem with that change, there has been a natural spike in newsgathering taking place over the Internet. Journalists have been investigating and reporting stories by reviewing website content and joining Zoom calls, e-conferences, and online conversations. Some have been chastised for some of their online newsgathering methods, with critics arguing that they amount to hacking or undercover reporting. For instance, in April 2020, the Financial Times suspended a journalist for listening in to a rival outlet’s Zoom call.91 Mark Sweney, FT suspends journalist accused of listening to rival outlets’ Zoom calls. THE GUARDIAN (Apr. 27, 2020); Financial Times reporter accessed private calls at Independent and Evening Standard. THE INDEPENDENT (Apr. 27, 2020), https://www.independent.co.uk/news/media/mark-di-stefano-financial-times-independent-evening-standard-zoom-call-a9485931.html. In November 2020, a login code was accidentally made public, so a Dutch journalist who joined the confidential call of EU defense ministers was accused of hacking the meeting.92 Dutch journalist gatecrashes EU defence video conference. BBC NEWS (Nov. 21, 2020), https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-55027641. In May 2021, reporters went undercover on a Zoom call with Prince Michael of Kent, the Queen’s cousin, posing as businessmen seeking royal connections in order to write a story about his supposed financial malfeasance.93 Sylvia Hui, Queen’s cousin accused of willingness to sell Kremlin access. ASSOCIATED PRESS NEWS (May 9, 2021), https://apnews.com/article/europe-entertainment-royalty-arts-and-entertainment-business-6b967250fade7070707d508c63fa31a9. In February 2022, Josh Renaud from the St. Louis Post Dispatch was warned by the governor that he’d “hacked” the government’s website when exposing its security weakness.94 Alex Heuer, Journalist accused by Gov. Pason speaks out: ‘He’s done me wrong.’ ST. LOUIS ON THE AIR (Feb. 16, 2022), https://news.stlpublicradio.org/show/st-louis-on-the-air/2022-02-16/wednesday-st-louis-journalist-at-center-of-parsons-hacking-claim-speaks-out. These forms of news reporting took on a new flavor, in part because of increasing time spent online, as well as law enforcement encouraging the closure of online meetings. In 2020, the FBI advised people not to “make meetings public” and to “manage screen sharing” to protect against Zoom bombing.95 WCVB Channel 5 Boston, YOUTUBE (Mar. 30, 2020), https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=N6iC05IND20.

With these calls, many meetings and phone calls that were traditionally open to the general public have been made private, creating hacking and undercover reporting risks for reporters. For instance, company investor calls and other previously public meetings now take place online in password-protected Zoom calls or behind click-through pages requiring privacy. In several instances, reporters have been advised not to join such calls or conferences — creating serious hurdles to their journalistic work — because entering could trigger risk of crimes, such as trespass, fraud, or the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act (CFAA).

This closure of information and the increased risk of potential criminal or civil liabilities under the CFAA and other areas of law are discussed below. While this is not the first time the CFAA has posed a risk to reporters’ work, it is in some ways an expansion of that problem as more events take place online. This issue is particularly concerning given that the Supreme Court’s recent opinion in Van Buren v. United States continues to permit possible liability through cease-and-desist letters and other threats of litigation.

The Computer Fraud and Abuse Act, a broad and poorly drafted anti-hacking law, has long posed a grave risk to journalism. The 1986 law imposes liability onto anyone who enters a computer “without authorization.”96 8 U.S.C. § 1030(a)(2)(C). This gives corporations broad powers to limit public access to information by simply creating barriers to entry of otherwise public data.

Spurred by the 1983 Hollywood blockbuster War Games, Congress initially passed the CFAA out of fear of the unknown risks associated with hacked computers, including such dire consequences as nuclear war.97 See Riana Pfefferkorn, America’s anti-hacking laws pose a risk to national security. TECHSTREAM (Sept. 7, 2021), https://www.brookings.edu/techstream/americas-anti-hacking-laws-pose-a-risk-to-national-security/; see also Jamie Williams, Our Fight to Rein In the CFAA: 2016 in Review. ELECTRONIC FRONTIER FOUNDATION (Dec. 28, 2016), https://www.eff.org/deeplinks/2016/12/our-fight-rein-cfaa-2016-review. While various policy initiatives have been waged against the CFAA, the statute is still often wielded by corporations to shield data often crucial to the public interest, even after Van Buren.

A. The importance of data to journalism

To understand how the CFAA poses jeopardy to journalism, it is important to recount how much reporters rely on data to tell stories, and have done so for centuries — particularly as data is often able to unveil narratives that otherwise are hard to tell. In 1895, investigative journalist Ida B. Wells compiled public records to publish the groundbreaking narrative on racism in America, A Red Record: Tabulated Statistics and Alleged Causes of Lynching in the United States, 1892-1893-1894. Through systematic data collection, Wells revealed for the first time the number of Black men who were lynched — painting a larger and more endemic story about racism in America.98 Brief of Amicus Curiae The Markup in Support of Petitioner, Van Buren v. United States (No. 19-793) (July 8, 2020), https://www.supremecourt.gov/DocketPDF/19/19-783/147271/20200708180752488_19-783%20-%20the%20markup%20amicus%20brief%20for%20e-filing%207-8-2020.pdf.

In the modern era, data collection has only become more central to tell otherwise unseen stories, particularly as these numbers are what catalog, quantify, and comprehend our world. Reporters in recent years have used a technique sometimes called web scraping — using online tools to crawl publicly accessible pages and create a dataset — to report on topics of public interest such as racial gaps in housing, racial biases in facial recognition technologies, and discrimination imbued in online advertisements.99 Brief of Amicus Curiae The Knight Institute, et al. In Support of Petitioner, Van Buren v. United States (No. 19-793) (July 7, 2020), https://knightcolumbia.org/documents/0fa799b380. Data scraping has also been used to unveil other major social wrongs, including doctors who sexually abused patients,100 See Carrie Teegardin, Behind the scenes: how the Doctors & Sex Abuse project came about. ATLANTA JOURNAL-CONSTITUTION (Dec. 17, 2016), https://www.ajc.com/news/opinion/behind-the-scenes-how-the-doctors-sex-abuse-project-came-about/UKFjNSqXoVOF9754k4wZ3M/. unsavory prison conditions,101 See David Eads, How (and Why) We’re Collecting Cook County Jail Data. PROPUBLICA (July 24, 2017), https://www.propublica.org/nerds/how-and-why-collecting-cook-county-jail-data. unfair credit scores,102 See Michelle Singletary, Credit scores are supposed to be race-neutral. That’s impossible., THE WASHINGTON POST (Oct. 16, 2020), https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/2020/10/16/how-race-affects-your-credit-score/. and broadband access bias.103 Leon Yin & Aaron Sankin, Dollars to Megabits, You May Be Paying 400 Times As Much As Your Neighbor for Internet Service, THE MARKUP (Oct. 19, 2022), https://themarkup.org/still-loading/2022/10/19/dollars-to-megabits-you-may-be-paying-400-times-as-much-as-your-neighbor-for-internet-service.

In addition to being able to uncover stories that would otherwise be difficult to tell, data reporting is a crucial tool as it creates accountability, permitting journalists to show their work and diminishing their chances of legal liabilities. This attribute of data reporting is crucial. When Reveal’s reporters scraped Facebook data to show the overlap between membership in law enforcement groups and extremist groups, the journalists were able to demonstrate to readers how they had reached their conclusions.104 Will Carless & Michael Corey, To protect and slur, REVEAL NEWS (June 14, 2019), https://revealnews.org/article/inside-hate-groups-on-facebook-police-officers-trade-racist-memes-conspiracy-theories-and-islamophobia/. In the three-part series, the reporters devoted an entire article to not only discuss how they used web-scraping tools to find their results, but also how they sought reaction from more than 150 law enforcement agencies about their involvement. Without this kind of proof checking, stories of this scale are often rife with libel claims.105 Will Carless & Michael Corey, These police officers were members of extremist groups on Facebook. REVEAL NEWS (June 27, 2019), https://revealnews.org/article/these-police-officers-were-members-of-extremist-groups-on-facebook/.

Third, data reporting has the added advantage of building trust with readers. The transparency accompanying data reporting goes a long way to show how reporters reach their conclusions and permit the public to double check. In 2020, when Reveal used web-scraping techniques to find that Detroit residents were wrongly charged hundreds of millions of dollars in property taxes, the reporters published the code they used to make the analysis.106 Accountability, The lost homes of Detroit. REVEAL, (Jan. 11, 2020), https://revealnews.org/podcast/the-lost-homes-of-detroit/. This information reinforced the story by not only making it more legally robust, but also helped readers determine how reporters reached these conclusions. Ironically, it is this kind of radical transparency about reporters’ tactics that makes them more vulnerable to companies who can identify them and use cease-and-desist letters to “close the digital gates.” Such threats are concerning, particularly following the Supreme Court’s recent decision in Van Buren.

B. How Van Buren v. United States still permits the CFAA to hinder data journalism

In June 2021, the Supreme Court issued its opinion in Van Buren v. United States,107 141 S. Ct. 1648, 1649 (2021). which narrowed the scope of the CFAA but left open opportunities for corporations to continue to wield it and limit access for reporters and the public.

The defendant in the case, Van Buren, was a police officer who accessed a police database to sell license plate information to a private citizen for thousands of dollars, in violation of department policy.108 Id. While the defendant had the lawful ability to enter the database itself, he misused his access for a wrongful purpose, and therefore was claimed by the government to have entered “without authorization.”

The relevant question before the Court was whether Van Buren had exceeded his “authorized access” as defined by the CFAA when his use of the data extended beyond the intended scope of the policy — or whether he hadn’t, because he had legitimate access to the database.

The majority opinion held that Van Buren did not violate the CFAA. As a police officer, he had the requisite credentials to access the database, even though he had done so for a prohibited purpose. The opinion, written by Justice Amy Coney Barrett, explained that because the government conceded Van Buren had accessed the law enforcement database system with authorization, that was the end of the inquiry.109 Id. at 1649. An individual “exceeds authorized access,” she continued, only when he accesses “particular areas of the computer — such as files, folders, or databases — that are off-limits to him.” This definition of “access” essentially turns on a “gates up or down” approach, she wrote. To violate the CFAA, a person must enter an area they would not otherwise be able to enter without additional circumvention.

Van Buren settled an ongoing dispute over whether the CFAA is a statute that creates liability through trespass or contract law. The importance of this distinction might seem highly academic, but in practice it has a large impact on journalists. The crux of the question is whether entering a computer is similar to a person crossing a property line (trespass) or violating a website’s terms of service (contract). Justice Barrett’s opinion seems to answer that question by holding that the CFAA is fundamentally a trespass statute.110 For decades prior to Van Buren, scholars questioned whether the basic wrong targeted by the CFAA is transgressing a person’s property boundary by essentially breaking a closed gate or breaking a promise made to the company through its terms of service. Therefore, Van Buren essentially decided that what the CFAA is concerned about is whether a person has crossed a website boundary, and not whether a reporter or other individual violates a website’s terms of service.

In general, this is good news for journalists. It means the law penalizes them only if they don’t have access to the website, and if they took a wrongful act to gain access to the site, perhaps by unlawfully obtaining a login code. On the other hand, simply accessing publicly accessible data even though it violates a site’s terms of service is not enough to cause liability. For example, if Facebook’s terms of service states no person can use its data for researching bias online, a violation of that policy is not enough to create a CFAA claim. “The statute is all about gates,” writes law professor Orin Kerr. “When a gate is closed to a user, the user can’t wrongfully bypass the gate.”111 Orin S. Kerr, The Supreme Court Reins in the CFAA in Van Buren. THE VOLOKH CONSPIRACY (June 9, 2021), https://reason.com/volokh/2021/06/09/the-supreme-court-reins-in-the-cfaa-in-van-buren/.

The ostensible purpose of this approach is that it penalizes the “so-called outside hackers” who lack “access privileges” and operate “without any permission at all.”112 Id. Journalists benefit greatly from this rule as they are able to scrape publicly available information from a website without hacking it, but often could be in violation of the company’s terms of service. Therefore, the trespass rule of Van Buren was widely preferred by many civil society organizations and amici-representing journalists, who were concerned about the contract approach to the CFAA because of how broadly terms of services could be applied.

In many cases, companies have drafted far-reaching terms of service where the “interpretation [was] so broad that it [swept] in ordinary journalistic activity that is essential to the newsgathering process.”113 Brief of Amicus Curiae Reporters Committee in Support of Petitioner, Van Buren v. United States (No. 19-793) (July 8, 2020), https://www.rcfp.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/2020-07-08-RCFP-Supreme-Court-amicus-brief-in-Van-Buren-v.-U.S.pdf. They began stating in their terms of service that even though online data was public, it still could not be used by the public. As the Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press, a nonprofit organization that provides pro bono legal representation and resources to journalists, wrote in its brief, “If that interpretation is permitted to stand, it would significantly chill the exercise of speech and press rights protected by the First Amendment, dramatically altering the way in which government officials and corporate whistleblowers relate to the press, the means by which the press gathers and reports the news, and the degree of newsworthy information made available to the public.”114 Id.

Even though Van Buren’s determination makes it seem that a violation of the CFAA would be much harder to prove, companies have been able to create more barriers as events move online. Increasingly as public information and in-person conferences have moved to sites requiring passcodes or private Zoom calls companies can take advantage of the “behind a gate” approach. In several instances, Reveal’s reporters have been thwarted from attending Zoom calls for events that previously would have been public, such as earnings calls, which are now often password-protected. Similarly, a state prison in Pennsylvania required phone calls (previously open to the public and allowed to be recorded) to be accessed only through Zoom calls that require visitors to consent to a list of checkboxes, including statements that attest “the making of a 3-way call” and “the recording … sharing … or … distributing of this visit is not authorized.”115 Screenshot on file with the author. Attending such online conferences, or Zoom calls while violating one of the checkboxes would now, under the rule of Van Buren, likely create a potential CFAA violation, in addition to giving rise to other legal claims. Reporters have therefore been unable to freely enter without risk.

Van Buren left another important question open: Can a website’s terms of service still have some negative impact under the CFAA? Can corporations still close their gates by drafting terms of service that are so broad that they are easily broken, such as by journalists scraping website data? Justice Barrett, writing for the Court, leaves this door ajar to corporations who wish to wield such broad provisions. She writes: “We need not address whether this inquiry turns only on technological (or ‘code-based’) limitations on access, or instead also looks to limits contained in contracts or policies.”116 141 S. Ct. 1648, 1659 n.8 (2021). Judge Barrett’s single line permits a corporation to ostensibly still continue to use “contracts or policies” to limit journalists’ access to their data.

The easiest way of doing this today is by sending cease-and-desist letters to individuals, such as reporters, advising them that their behavior violates the terms of service, and so any advance onto the website could also amount to trespass.

For example, in 2016, in Facebook v. Power Ventures, the Ninth Circuit found that a cease-and-desist letter threatening suit and revoking authorization was sufficient to create a CFAA violation, even though Power Ventures had not clearly violated Facebook’s terms of service.117 Facebook, Inc. v. Power Ventures, Inc., 844 F.3d 1058, 1067 (9th Cir. 2016). In that way, Van Buren leaves open the door to companies’ blocking access by simply sending a bullying letter to a reporter. As the Electronic Frontier Foundation wrote in June 2021, “Service providers will likely argue that this is the sort of non-technical access restriction that was left unresolved by Van Buren.”118 Aaron MacKey and Kurt Opsahl, Van Buren is a Victory Against Overbroad Interpretations of the CFAA, and Protects Security Researchers. EFF (June 3, 2021). https://www.eff.org/deeplinks/2021/06/van-buren-victory-against-overbroad-interpretations-cfaa-protects-security; Issie Lapowsky, Van Buren v. United States: The SCOTUS case splitting the privacy world in two. PROTOCOL (Nov. 30, 2020), https://www.protocol.com/van-buren-v-united-states-supreme-court. Similarly, law professor Eric Goldman wrote in 2021, “I think courts are likely to continue treating C&Ds [cease and desist letters] as sufficient to withdraw authorization for CFAA purposes.”119 Eric Goldman, Do We Even Need the Computer Fraud & Abuse Act (CFAA)?–Van Buren v. US. TECHNOLOGY AND MARKETING LAW BLOG (June 9, 2021), https://blog.ericgoldman.org/archives/2021/06/do-we-even-need-the-computer-fraud-abuse-act-cfaa-van-buren-v-us.htm. But “[t]his stance always strikes me as backwards,” he continued. “It means that C&Ds — unilateral demands from the sender that are often only loosely tethered to the law — have greater legal effect than properly formed bilateral contracts (TOSes).”120 Id.

This feared hypothetical came to pass when Facebook cited the CFAA in an October 2020 cease-and-desist letter sent to New York University academics who were researching the impact of advertisements on Facebook. The research, conducted by the NYU Ad Observatory, recruited more than 6,500 volunteers to collect data from Facebook about the political ads the platform showed them. Facebook’s letter stated that the NYU research had violated the company’s terms of service and put it at risk of violating its own consent decree with the Federal Trade Commission. The letter came at a time when Facebook advertisements were under intense public scrutiny just a month before the U.S. presidential election.

Empowered by Van Buren’s position, Facebook subsequently disabled the accounts of the academics in August 2021. While many researchers and journalists continue to rely on access to Facebook’s data and programming software, such as Application Program Interfaces (APIs) and other information on the platform, to understand matters of public importance (like the discriminatory impact of online housing ads121 Julia Angwin and Terry Parris Jr., Facebook Lets Advertisers Exclude Users by Race. PROPUBLICA (Oct. 28, 2016), https://www.propublica.org/article/facebook-lets-advertisers-exclude-users-by-race and the traction of fake news online)122 Issie Lapowsky, The most engaging political news on Facebook? Far-right misinformation. PROTOCOL (Mar. 3, 2021), https://www.protocol.com/facebook-misinformation-far-right-politics Van Buren creates a blueprint for other companies to use the threat of a cease-and-desist letter to stifle reporting.

Some of these questions may have been resolved in hiQ Labs, Inc. v. LinkedIn, which was remanded by the Supreme Court to the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals in 2021.123 hiQ Labs, Inc. v. LinkedIn Corp., No. 17-16783, 2022 WL 1132814 (9th Cir. Apr. 18, 2022). Central to this litigation was hiQ, a small startup scraping LinkedIn data to make a human resources tool to sell to employers. When LinkedIn found out, it sent hiQ a cease-and-desist letter; hiQ filed suit to prevent LinkedIn from taking legal action against it under the CFAA for scraping LinkedIn’s publicly available data.

While the district court ultimately ruled in hiQ’s favor by finding that scraping of public data didn’t violate the law, a decision affirmed by the U.S. Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals, LinkedIn petitioned the Supreme Court to take up the case. On June 14, 2021, the Supreme Court remanded the case back down to the Ninth Circuit in light of Van Buren. In April 2022, the Ninth Circuit held Van Buren affirmed that the hiQ Labs case was correctly decided and that “the concept of ‘without authorization’ does not apply to public websites,”124 Id. at *14. particularly where “access is open to the general public [then] permission is not required.”125 Id.

In reaching this conclusion, the Ninth Circuit expressed a concern over “information monopolies.”126 Id. at *17. The opinion by U.S. District Judge Edward M. Chen noted that, while the public has an interest in preventing bad-actor hacking or improper use of data, there is no public benefit in LinkedIn or other companies having “free rein to decide, on any basis, who can collect and use data — data that the companies do not own.”127 Id.

While the Ninth Circuit’s opinion is good news for reporters, how other courts of appeals interpret Van Buren remains to be seen, and whether they adopt the Ninth Circuit’s is similarly to be determined. Moreover, the facts of this case stress the Ninth Circuit’s view of whether information is “public” may vary if the user “demarcate[s the information more clearly] … as private,” including through “authentication system[s]” like usernames and passwords readily available on Zoom and other software.128 Id. at *14, 16.

While hiQ affirms that CFAA claims are less likely where information is public and easily accessible, it encourages companies to simply put more and more information behind closed gates — leaving liability in those instances to be more complicated, even under Van Buren.

In 2022, a federal district court in Virginia held in Carfax, Inc. v. Accu-Trade, LLC that a company that once had access to data that had “since been rescinded by the information provider” could have a CFAA claim established against it if “affirmative notice of the revocation” had been made.129 Carfax, Inc. v. Accu-Trade, LLC, 2022 WL 657976, at *14 (E.D. Va. 2022). Relatedly, in WhatsApp LLC v. NSO Group Technologies Ltd.,130 WhatsApp Inc. v. NSO Group Technologies Ltd., No. 4:19-cv-07123 (N.D. Cal.). WhatsApp successfully litigated a CFAA claim against NSO, an Israeli spyware company, for its hacking of WhatsApp users. NSO brought their arguments all the way up to the Supreme Court, but the Court denied the petition for certiorari in January 2023. These cases all seem to show that while application of the CFAA is context-dependent, the more a company can put information behind walls, the easier it is to allege a claim.

In addition to claims under the CFAA, reporters embedding themselves in various private Zoom calls and closed online events are increasingly at risk of being held liable under other areas of law, such as state law claims of fraud, trespass, conspiracy, and breach of contract. These kinds of cases have historically arisen in the rare instances of undercover reporting,131 Desnick v. American Broadcasting Companies, 44 F.3d 1345 (7th Cir. 1995); Food Lion v Capital Cities/ABC, Inc., 194 F.3d 505 (4th Cir. 1999). but today these fact patterns have become more common with the proliferation of online events.

Such a case was decided in August 2022 by the Ninth Circuit National Abortion Federation v. Center for Medical Progress.132 National Abortion Fed’n v. Center for Med. Progress, Case No. 15-cv-03522-WHO (N.D. Cal. Aug. 27, 2015). In that case, David Daleiden, an anti-abortion activist, went undercover to the National Abortion Federation (NAF) conference, obtaining 500 hours of surreptitious footage and then publishing it online, claiming the publication was protected under the First Amendment.133 Id. Daleiden had posed as a procurer of human fetal tissue for a fake biomedical research company to infiltrate the conference.

In the district court, NAF successfully sought an injunction against him for illegally obtaining the information in breach of contract on the website hosting the conference, and claiming release would cause damage.134 Id. Two years earlier in 2019, a federal jury awarded Planned Parenthood nearly $2 million after finding the same activist had caused the organization substantial harm, letting the judge reach its conclusion that similar harm would result. See Maria Dinzeo, Jury Finds Abortion Foes Harmed Planned Parenthood, Awards Over $2 Million. COURTHOUSE NEWS SERVICE (Nov. 15, 2019), https://www.courthousenews.com/jury-finds-abortion-foes-harmed-planned-parenthood-awards-870k/. Daleiden appealed to the Ninth Circuit, arguing that the First Amendment protected his ability to newsgather, but the Court held that his First Amendment rights had been knowingly, voluntarily, and intelligently waived by signing the agreements with NAF in its terms of service online. In essence by signing the terms and conditions Daleiden, the Court held, unambiguously prohibited him from disclosing recordings, and from disclosing any information he received from NAF.

Although journalists are generally discouraged from conducting undercover reporting135 Food Lion v. Capital Cities/ABC, Inc., 887 F. Supp. 811 (M.D.N.C. 1995) (holding that claims against the news outlet for doing undercover reporting did not warrant dismissal, but that plaintiff could not recover damages for injuries to its reputation as result of broadcast). Daleidin’s case demonstrates a likely hurdle for reporters who wish to engage in undercover reporting even if aided with extensive editorial, ethical, and legal review. These kinds of liability, i.e. claims of fraud and breach of contract, like the kind Daleiden incurred, are increasingly more common in our online world. As more companies are holding conferences and events online, requiring password-protected entrance to events and terms and conditions that prohibit filming and distribution, these events become closed to reporters. Violating these terms could induce liability even if done undercover. This is especially aggravating when many of these events used to be open to the public.

For instance, more investor calls, as previously discussed, are password protected and require terms and conditions to be signed prohibiting disclosure. Similarly, other online events like panels or conferences now require visitors to agree not to publish information that they gather. As stated earlier, one such statement required a visitor to attest that “the recording … sharing … or … distributing of this visit is not authorized.” By agreeing to these kinds of statements, reporters are then vulnerable to claims like the kind alleged against Daleiden. Thus with companies being able to more easily close these online events to the public, reporters must increasingly be careful not to violate the CFAA and dozens of other potential civil or criminal state laws.

C. Conclusion

In conclusion, the problem of the CFAA is that it essentially transforms research, journalism, and fact-finding into criminal behavior and puts the power of categorizing that criminalization into the hands of corporations. Companies incentivized by financial gain, avoidance of corporate embarrassment, and protection of proprietary information are given tools beyond their scope. In the case of Van Buren, the primary legal violation was that of an employee who disclosed information behind a private wall. As Eric Goldman wrote, “The fact that Van Buren committed these violations using a computer database feels mostly irrelevant. … For that reason, shoehorning Van Buren’s activity into the CFAA feels gratuitous.” Similarly, shoehorning journalists’ research of data that is mostly visible online seems like an unconstitutional way to threaten the press from writing truthful stories on important public information.

While an immediate solution is unlikely, the most obvious answer would be for Congress to revise the CFAA to remove these ambiguities, as various activist and civil society organizations have long advocated. In addition to a legislative fix, companies should stop sending frivolous letters that only intimidate reporters and deny access to information important to the public, as well as changing previously public events to private.

Finally, courts interpreting Van Buren should clarify that its narrow ruling clearly suggests that access to information should not be stifled where members of the public have gained access freely and with ability.

Expansion of withholding data as “confidential business information” and “trade secret” under the Freedom of Information Act’s Exemption 4

Perhaps the largest block to critically important corporate information stems from the expansion of trade secrecy law, particularly under the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA), a statute that generally requires the government to disclose public records unless one of FOIA’s nine exemptions apply.

In 2019, the Supreme Court case Food Marketing Institute v. Argus Leader Media expanded FOIA’s Exemption 4, which permits the government to withhold records containing trade secrets and confidential business information.136 Food Marketing Institute v. Argus Leader Media, 139 S. Ct. 2356 (2019). Previously, Exemption 4 required the government to show that the disclosure of the information would substantially harm the industry. Under Argus Leader’s new test, however, companies are allowed to simply rubber-stamp information as “confidential” to have the government exempt it from disclosure requirements.

Increasingly, federal and state governments have used this expansion of “confidential business information” to withhold records involving important health information, corporate pollution records impacting the environment, corporate injury records, and diversity statistics of federal contractors. Generally, Exemption 4 records are often held by states when corporations perform government work in lieu of the government, so their information inherently demands accountability as these companies are performing government work. Additionally, the state may demand these records for corporate accountability around matters of public interest. However, the Argus Leader decision permits companies to withhold under Exemption 4 of FOIA. The statute has nine narrowly drawn exemptions, the fourth of which permits the government to withhold trade secrets and confidential business information. Several cases have been litigated interpreting this decision in the lower courts, slowly hemming in the overly expansive view of the decision. This section of the paper will delve into the history of Argus Leader and possible reinterpretations of the case, based on these lower court decisions.

In 2019, the Supreme Court relaxed its requirements for when the government can withhold public information under Exemption 4 of FOIA. In general, Exemption 4 protects “trade secrets and commercial or financial information obtained from a person [that is] privileged or confidential.”137 The Freedom of Information Act, 5 U.S.C. § 552(b)(4) (1967). Because the term “confidential” is not defined in FOIA, courts over the years have applied various tests to determine what qualifies as confidential.138 At least part of the confusion surrounding Exemption 4 must be attributed to what has been described as “the tortured, not to say obfuscating, legislative history of the FOIA.” 9 to 5 Organization for Women Office Workers v. Board of Governors, 721 F.2d 1, 6-7 (1st Cir. 1983), quoting American Airlines, Inc. v. National Mediation Board, 588 F.2d 863, 865 (2d Cir. 1978). Justice Stephen Breyer summed it up well by stating that the definition of “confidential” within the meaning of Exemption 4 has troubled the courts since the enactment of FOIA. For many years, courts of appeals determined records were “confidential” if the government provided an express or implied promise of confidentiality to the submitting company.139 General Services Administration v. Benson, 415 F.2d 878, 881 (9th Cir. 1969). Subsequently, courts considered whether the information was of the type customarily released to the public.140 Sterling Drug, Inc. v. FTC, 450 F.2d 698, 709 (D.C. Cir. 1971); see also M.A. Schapiro & Co. v. Securities & Exchange Com’n, 339 F. Supp. 467, 471 (D.D.C. 1972).