In the aftermath of the 2016 U.S. presidential election, numerous analysts have criticized the polarized nature of media and its failure to include perspectives that reflect the ideological and demographic diversity of the country. Many have argued that media must do more to listen to multiple publics.

Curious City, a radio series based at WBEZ Chicago Public Media, has been trying to do just that. Since its inception in 2012, it’s produced traffic-generating stories developed from questions nominated by listeners. However, question-askers tended to come from areas of metro Chicago that were public radio strongholds. Seeking to expand its question base, Curious City undertook an outreach project in 2016 focusing on underrepresented areas of the city—primarily African-American and Latino neighborhoods on the South and West Sides of the city, as well as some predominantly white suburbs. Using a combination of face-to-face outreach, outreach via community partners, and social media marketing, the team attempted to determine the best method for generating “novel” questions from target areas during this experimental period.

This report asks what we can learn from Curious City’s digital and offline strategies to expand the demographics of people whom media is listening to. It draws from my observations of the program’s outreach process and twenty-five interviews with journalists, participating audience members, residents of targeted outreach areas, and partner organizations. It also offers an opportunity to reflect on journalistic norms and approaches to participatory media, how community stakeholders interact with local news, and relations between public media and marginalized publics.

The first section offers an overview of the Curious City model—which uses Hearken, a digital engagement platform now being employed by more than seventy newsrooms in the United States and internationally. It looks at how this approach fits within contemporary audience engagement approaches. The second section outlines Curious City’s outreach project, the strategies employed, and WBEZ’s reflections on the series’ efficacy: not only the number of questions generated, but also the type of questions, and the pros and cons of various approaches. Staff members also reflected on negotiating expectations and power dynamics as they entered communities where they were often perceived to be outsiders.

Section three explores how the project did and did not challenge traditional journalistic norms regarding audience engagement. It examines how the public was or was not involved in the process of producing stories—from the selection of stories, to reporting them, to soliciting feedback following their broadcast. The fourth section examines the extent to which Curious City’s outreach initiative affected relationships between local stakeholders. In particular, it looks at the idea of a community “storytelling network” that connects media, community organizations and institutions, and residents.

Through its outreach project, Curious City has made headway as an engagement tool through many, if not all, phases of story production. Ultimately, for media outlets to make a more effective contribution to democratic dialogue in the United States, engagement projects must explore pathways that help them listen to audiences, integrate input into reporting, and offer shared spaces for community members to discuss with each other. While the project focused on demographic and geographic inclusivity more than political ideology, lessons learned regarding engagement could inform a range of projects pursuing more inclusive media. This report offers analysis of the project’s successes and limitations, in the hopes of providing suggestions for how to expand audience engagement beyond the publication or broadcast of stories for all journalists.

Key Findings

- Curious City found, as expected, that expanding the base of residents from which it sourced increased the variety of ideas and questions generated. While outreach to residents who were not familiar with WBEZ required a greater investment of time, the ideas these efforts yielded deviated from typical or expected ones and produced more novel questions. In addition, questions from previously underrepresented communities generated accountability stories (e.g., focusing on inequitable distribution of resources, local governance, etc.) grounded in local experiences.

- Engagement efforts were most effective when online technologies were combined with face-to-face outreach. These were most efficient when Curious City partnered with local institutions with aligned missions.

- The Curious City model and outreach efforts challenged standard journalistic practices around story selection by broadening the pool of possible story ideas. The resulting stories would have had difficulty making it through the normal editorial process (due to, for example, a lack of a time-sensitive news peg) had they not been nominated by a listener.

- The Hearken platform is designed to strengthen links between media and the public. But in the case of Curious City, the platform was mostly used to engage the public in story selection and production—and less so for distribution and feedback due to a lack of in-community marketing.

- Curious City’s outreach initiative also offered the possibility of strengthening storytelling network ties between regional media, hyper-local and ethnic media, and community organizations. Some connections were made that offer potential for future development. However, due to mission and resource priorities, these links were not prioritized as a goal in themselves.

Recommendations

News media organizations interested in strengthening their relationships with their audiences and communities through digital engagement technologies such as Hearken should do so in combination with offline, face-to-face outreach. Targeted offline interactions and events offer opportunities to connect with residents who may be unaware of the outlet or unfamiliar with how or why to engage. Outreach initiatives can incorporate in-community marketing to build upon connections made by face-to-face interactions. Even low-tech, low-budget strategies such as basic flyers, street signs, hosting, and/or advertising follow-up community events, etc., may be useful to build ties with residents. Media organizations should explore collaborations with community partners to conduct outreach. Community stakeholders with aligned missions such as public libraries may make especially strong partners. These partnerships may be strengthened and made more sustainable by ensuring that all sides of the partnership benefit. For example, libraries may find value in connecting audience questions to available books, classes offered, or follow-up community events held on site. Regional media outlets should explore partnerships with hyper-local and ethnic media outlets to further the reach of engagement initiatives by exchanging content and/or cross-promoting initiatives and events. Such relationships can be mutually beneficial, as well as strengthen the local media ecosystem and storytelling network.

Curious City and the Engagement Journalism Field

Do lottery dollars really fund education? Why are there so many revolving doors in Chicago? Why can’t viaducts on the South Side of Chicago have beautiful murals like the North Side?

These are some of the many questions that WBEZ’s Curious City project has answered. At least once a week, the project tackles a query posed by a listener, which ranges from whimsical pondering to critical theorizing about city politics and systemic inequality. Listeners submit questions online in response to the question: “What do you wonder about Chicago, the region, or its people that you want WBEZ to investigate?”

After questions are shared, they are screened by Curious City’s editorial team, which either chooses to do a story directly or puts the question into a “voting round” where listeners are invited to select the question they would like to see reported. Selected questions are assigned to either a WBEZ staff member or freelance reporter, who then loops back to the original question-asker to see if they would like to participate in the process. Involvement may range from a simple phone chat to clarify the question, to accompanying the reporter to conduct interviews in the field or studio. Stories are then produced and edited, and may be shared in a variety of formats—usually both as a radio story and a multimedia story online.

The Curious City model fits within the broader umbrella of engagement journalism or social journalism.1 These are taxonomies of journalism that seek more participatory and connected relationships with audiences, and challenge the one-to-many model of producer and audience 2. While a number of media outlets have engaged with concepts of citizen journalism and community contributors,34 these have often been limited due to a combination of resource challenges and concerns regarding editorial and production standards. In recent years, several outlets have undertaken hybrid initiatives to engage “the people formerly known as the audience”5 in the storytelling process, without completely relinquishing the professional journalist’s grip on the pen or microphone. In addition to Curious City, these have included projects such as the Listening Post, the Public Insight Network, and others that at minimum interact with community members to source story ideas, with varying degrees of outreach and follow up. Such projects claim to open a degree of agenda-setting space to community members, albeit while retaining editorial gatekeeping powers.

Hearken’s “Public-Powered” Journalism Model

Curious City was originally piloted as an initiative funded by the Localore public media innovation fund, before becoming integrated into WBEZ’s operations. Curious City’s creator, Jennifer Brandel, then developed the Hearken digital engagement platform as a tool to make it more efficient to gather and manage questions from listeners. Brandel went on to turn Hearken into an independent company, and the digital platform is now used by newsrooms across the United States and abroad.

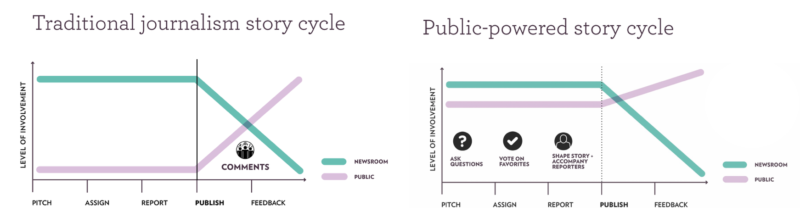

Hearken puts forward a model that its innovators call “public-powered journalism,” which they argue reimagines the “story cycle” of journalism. In traditional journalism structures, outside of breaking news, coverage is often determined through a process of pitching. A reporter may get an idea for a story from a source they have cultivated, a press release they receive, or something they read in another media outlet. This idea is then presented as a pitch—an argument for why the idea is important and why it can be crafted as a story with characters, actions, and scenes. An editor, who is meant to be a surrogate for the audience, then scrutinizes this pitch. The editor decides whether the story has interest and value from the perspective of the public the outlet seeks to serve, as well as other editorial considerations regarding timeliness and newsworthiness.

Figure 1. Traditional journalism story cycle versus Hearken’s “public-powered story cycle.” Source: Courtesy of Hearken7

Hearken, however, allows newsrooms to involve residents earlier in the process—asking questions, voting on them, and participating in the reporting. In the case of Curious City, listener questions are fed into the Hearken platform and seen by Curious City’s editor, producers, and other staff reporters involved in the project. Questions are then discussed in team meetings. Some questions are plucked out of this pool, either by the editor or a reporter who is interested in pursuing the story. Other questions are fed into a voting round, or set aside. Question-askers are then involved to varying degrees throughout the rest of the story cycle.

Curious City’s Outreach Project

Editor Shawn Allee thought there might be a problem when he noticed Curious City was getting some of the same questions suggested multiple times. While it wasn’t a surprise that more than one person in the region was wondering if the recycling items put in Chicago’s blue bins really got recycled, he noticed that many questions seemed to be coming from the same neighborhoods. “I figured that we were probably going to be running into a problem where we’re kind of captured by our own audience in some way—if we’re working so closely with them,” he said. “I kept thinking, well, who are we not [working with]?”8

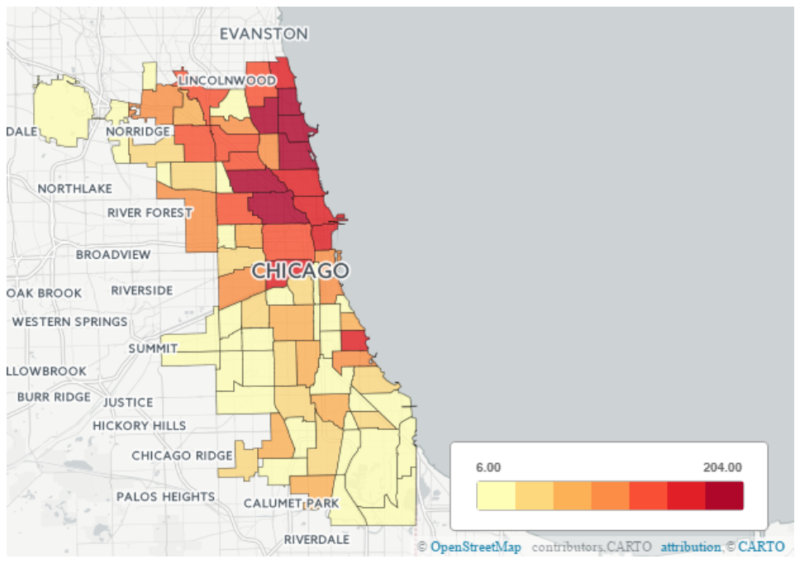

Figure 2. Distribution of Curious City questioners by Chicago Community Areas. Source: Courtesy of WBEZ’s Curious City10

To answer this question, starting in the summer of 2012 and running through February 2016 Allee mapped where question-askers in the city and larger region reported living on their online question forms. Unsurprisingly, areas considered WBEZ strongholds tended to have the largest share of questions. Fewer questions came from the city’s South and West Sides, largely home to African-American and Latino communities, or from many largely white suburbs. Given the station’s mission to cover the entire region, Curious City sought and received support from the McCormick Foundation11 to experiment with different strategies for soliciting more questions from a broader range of geographies.

Curious City commissioned an outreach producer to lead on the collection of questions from areas with a history of fewer question-askers. This was done using three primary methods. First, the producer would physically go to target areas and attempt to speak with residents face to face. Residents were approached in places such as parks and bus stops, and invited to ask a question about “Chicago, the region, or its people.”

The second strategy involved partnering with various community institutions, organizations, or businesses to solicit questions. With some partners, including several suburban libraries and a microbrewery cafe, Curious City would leave a box and a short paper form for residents to submit their question. Curious City also tried a hybrid model where it worked with partners, in this case library branches, to set up a table to talk to library visitors about the project and collect their questions. The series also attempted to establish links with some hyper-local and ethnic media outlets by offering them free Curious City content adapted for print as a way to publicize the project and show their readers how to participate.

The final strategy involved an online marketing campaign. Using both standard and carousel Facebook ads, the campaign targeted demographic “look-alikes” of WBEZ listeners within geographic areas with fewer question-askers. To ensure relevance to its geographic areas, Curious City created banners and landing pages for underrepresented portions of Chicago, suburbs, and Northwest Indiana. The pitch to solicit questions was tailored to include references to Northwest Indiana or the suburbs, in addition to Chicago. According to Curious City’s white paper for the McCormick Foundation, the Facebook campaign, which ran for three weeks, cost close to 4,500 dollars to buy ads reaching just under 200,000 users.

Over the course of the outreach project, I observed the outreach producer as he gathered questions in various areas, and I sat in on team meetings. I conducted six interviews with Curious City team members—staff and freelance reporters, producers, as well as the editor. I interviewed eleven residents whom the outreach producer approached in areas targeted by the campaign, as well as three representatives of community institutions participating in the project. To better understand how past participants from public radio stronghold areas thought about Curious City, I also interviewed five past question-askers from areas not targeted by the outreach campaign.

Which Outreach Method Was Most Effective?

After nearly a year since beginning the outreach project, the team members analyzed their findings. In total, they were able to gather 313 questions through outreach to target geographies (out of a total of 976 questions gathered during the project period). They found that the most productive and efficient method was face-to-face events at libraries, which produced 159 questions. Face-to-face outreach independent of any partner produced 137 questions, though required a larger investment of time and resources traveling from location to location. The Facebook marketing campaign generated 1,920 clicks on the ads, but only fourteen of these people submitted questions. Question boxes left with partner institutions only generated three questions. This was attributed to a lack of sustained promotion of the project by partner organizations’ on-site staff.

From this pool of questions, during the project period, three stories were produced and broadcast as Curious City stories, with a fourth in the planning stages. All of these were selected by the editor and did not go through a voting round. Curious City has a relatively long production cycle as some questions are produced more than a year after they’ve been received. They may be fed into a voting round or selected later based on available staffing, seasonal logistics, or other editorial considerations. For this reason, it is possible that other questions generated by the outreach may be produced at a later time.

Critically, Curious City’s team concluded that the outreach project did “move the needle closer to geographic parity.”12 It found that the percentage of questions coming from previously underrepresented zones grew at a faster rate than WBEZ’s core audience. While the rate of growth of questions from core audiences was twenty percent, the rate for Chicago’s West Side was seventy-eight percent and fifty-three percent for Chicago’s South Side. The suburbs also grew faster than the core audience. Only Northwest Indiana lacked substantial growth.

Team Reflections on Process

It is worth noting that all Curious City questions go through a rigorous editorial process, as was illustrated at team meetings. Meetings were held around a table in the project’s corner of WBEZ’s buzzing, open floor plan newsroom. Behind them, Post-it notes affixed to a computer monitor seemed to satirize the jargon of audience metrics: “1) Grow audience. 2) Kill audience. 3) Eat audience.” The editor, Allee, and the multimedia producer spent nearly an hour vetting which questions should be selected for upcoming voting rounds. Each round contained three questions clustered by an overarching theme. During the meeting, the producer shared several possible groupings of questions with internal working themes such as business, the natural world, and sub-communities. Questions under consideration were a mix of the newly submitted and second-place runners-up from previous voting rounds.

Over the course of discussing the pros and cons of each category, several editorial considerations were raised. Allee rejected a question related to a lead contamination incident, as the newsroom was already covering a similar story. A question that would have required gathering sound outside was tabled due to the dictates of Chicago weather. A series of questions related to Chicago bars was held for later out of concern for its tone. “We can only do so many of a particular topic or tone,” explained Allee, adding that his team tried to include a mix of “fun” stories versus “reporter-y” stories, history stories versus accountability stories, etc.

Going through some of the questions, Allee occasionally noted that such-and-such staff reporter or regular freelancer had interest or expertise related to a particular question. Questions were also considered with an eye toward expanding geographical coverage. When looking at a question tied to Lake Michigan, Allee noted that they could cover the story regionally by basing the story in Indiana or a northern suburb. The discussion was also mindful of who was asking the question. When three different listeners asked the same question, they chose the version proposed by a question-asker who appeared to be Latino (when the other two question-askers appeared to be non-Hispanic white). When they had to makes choices between equally valuable questions, they would attempt to include a listener who either came from a location in the city they heard from less frequently, or from a listener who was a person of color or other less represented group. They would then notify the other question-askers that a question similar to theirs was going to be addressed.

The team members also considered the perceptions of audience members when questions were tied to specific cultural backgrounds. For example, they rejected a grouping of questions that would have pitted a question related to Koreatown against a question related to Chinatown, explaining that they did not want to create situations which could be perceived as setting ethnic groups up to compete against one another.

Interestingly, many questions from outreach areas focused on issues of accountability (regarding the distribution of resources across the region and issues within local governance, for example). All three outreach stories produced to date have been accountability stories. Nevertheless, Allee and Curious City’s outreach producer said that while it was not surprising to receive accountability questions from areas they were targeting, which included Black and Latino communities with histories of disinvestment, they sought to be open to all types of questions from residents of these areas: “Sometimes, a lot of times, they’ll say something that is meaningful and local to them. But sometimes they won’t,” said Allee. “Sometimes you’ll go to a park on the West Side or South Side or suburb or something and they’ll ask about something downtown.”13

He explained that when they were starting the project, many station staff assumed that the goal of expanding coverage geographies would dictate topics. In particular, given that the areas included primarily African-American and Latino neighborhoods with a history of inequalities, it was presumed that the show would be more likely to cover issues such as poverty, racism, and segregation. Said Allee:

And I said I haven’t heard from these folks yet. I don’t know what they’re going to ask. . . . I can’t predict for sure. What I can predict is that if we ask more people from these communities, we’ll get more questions. We’ll get more voices. And since part of our job is to be genuine and listening to them, then, I can sleep better at night at least knowing that I listened—and that it informed my editorial decision-making.14

They did not want to be “tipping the scales” on what topics people’s questions covered, added Allee. He pointed out that if the station felt it should be doing more coverage of specific issues as an organization, WBEZ should be assigning those stories directly. He wanted Curious City to remain open to all kinds of questions from residents of these communities.

While Curious City staff members framed their initiative as an experiment, they acknowledged their approach was more subjective than “scientific.” For example, when the outreach producer went to a target area to seek questions, he acknowledged that the locations he chose skewed whose voices were represented: “It’s limiting because of who is at a park at eleven o’clock in the morning on a Tuesday. So, in that way, I think you’ve got a certain subset of people that’s not representative of the entire population.”15

Walking next to a park in a northern suburb, the producer also reflected on how he chose whom to approach. Allowing a group of power walkers to pass, he explained that he weighed the “kind of barriers you have to get through for the reward.” He calculated the amount of work and time required to get a group of residents to agree to participate and share questions. In the case of the walkers, he decided he would be unlikely to win them over in an efficient way. Other residents were not pursued for other reasons: “It’s all happening kind of at a subconscious level. I’m not doing it on purpose. Like, did you see that [pointing to a couple who disappeared behind some bushes]? Did that look promising?” 16

The producer attempted to be mindful of how the combination of his own implicit bias and how residents perceived him shaped their interactions. He talked to people with a personable and informal manner. Nevertheless, some awkwardness is unavoidable when approaching strangers, uninvited, in public spaces, particularly when the reporter is a visible outsider in terms of race and/or geography.

Engagement Across the Storytelling Cycle

The larger Hearken model of weaving engagement throughout the story cycle—from story selection, to reporting, to distribution and feedback, calls for significant rethinking of the role of journalist as producer and audience as receiver. But how does this engagement model play out in practice in the case of Curious City, particularly given its efforts to expand which residents are engaged?

From Question to Story Selection

As noted, over the course of the outreach project, Curious City saw the percentage of questions coming in from predominantly African-American and Latino neighborhoods on the city’s West and South Sides increase considerably. This process fed questions into the editorial system from residents who lacked familiarity with Curious City or WBEZ. As a result, the spectrum of questions was topically more variable given that question-askers had no preconceived idea of what made a “good” Curious City question. One of the challenges of the outreach project was for outreach staff members to quickly explain why they wanted people to frame their curiosities in the form of a question. “I think a lot of people start with statements,” a reporter who solicited questions at a branch library explained. “Like, ‘I’ve seen blah blah blah,’ and then, ‘What’s up with that?’ Basically, ‘I want you to tell me more about this thing.’”17

Gathering questions in-person allowed for some flexibility in such situations. The outreach producer explained how in some instances he would coach people through the process of thinking of a question they had about a topic. One of these sessions resulted in a question from a resident of the Pill Hill neighborhood on Chicago’s South Side: “Why can’t viaducts on the South Side have beautiful murals like the North Side?” The question-asker believed she knew the answer to this question—structural racism and inequitable resource distribution. But while this was acknowledged in the story, the reporter returned to the question-asker in the piece to share his findings, which included some different political and logistical factors. The editor explained the approach:

I think we needed to be really clear with the listeners, that she’s not coming from a vantage point that she doesn’t think she had an answer already. We didn’t think that would be fair to the listener. And it actually helped us in the end because it was useful, because she was able to critique some of the things that we found. In a meaningful way, but not in a mean way. . . . That gave us the space to deliver things that maybe she should rethink, or at least consider in her analysis.18

The story incorporated the question-asker’s perspective, not just in story-selection, but also in reporting. The transparency of the process allowed for both the question-asker to air grievances, and opened an opportunity for the reporter to add nuance to an assumed narrative.

Of course, it was not always possible to get questions from residents within outreach areas. Some residents refused to talk to the outreach producer. Others did not formulate their thoughts as a question. On a field outing in the far northern suburb of Waukegan, the outreach producer met an African-American man at a noisy bus stop. The young man shared some of his family’s experiences, their hardships, and the fact that they now hoped to move away from the Chicago region. The man did not share a question, but the producer noted his comments: “He said things that were really unique. I’ve never heard people say, ‘My family’s been struggling for generations. There’s no future here for African Americans.’”19 The experience gave the producer ideas for possible follow-up stories. Although these did not directly feed into Curious City in this instance, the outreach process did contribute to the larger mission of connecting WBEZ to perspectives it may not encounter otherwise.

Editorial Gatekeeping

While the outreach process expanded the range of questions considered, Curious City operated within an editorial structure where an editor continued to hold gatekeeping powers. As discussed above, not every question made it into a voting round—the questions in these rounds were curated. They were all questions that the team agreed would be possible to do, and that it had the capacity to accomplish.

Nevertheless, for journalists involved in this process, using questions as a starting point offered a justification for broadening a spectrum of possible coverage. Several producer and reporters noted that the Curious City model gave them tools for pitching stories that otherwise would not have made it past editorial gatekeepers.

As one freelance reporter shared, “When I pitch stories as a freelancer, it always . . . almost always, has to have some sort of hook or news peg.” He said for one of his most popular Curious City stories, he had “no reason at that moment to be doing that story other than the fact that someone asked the question.” And yet, he argued, the story had value: “Sometimes I think the focus on what’s important to what’s happening in the news right now, you lose sight of the fact that there are things just sitting there that are worth writing about, reporting about.”20

Another journalist explained that for him the appeal of Curious City was that it removed the editorial hurdles to producing high-quality, creative, local stories:

If we determine people are curious about it, that’s enough for us. We’re not going to sit around and have an edit and be like, “Really, do the public really want to hear this? What are we going to add that’s different to other people’s reporting?” Because if you hear that people are interested in it, and you ask them why they are interested in it, you can kind of skip a lot of those editorial conversations that I sometimes find frustrating.21

A reporter shared a term for the kind of editorial hazards Curious City helped to avert: “stupid editor ideas.” Stating that while she loved her editors, this industry-wide phenomenon tends to consist of ideas springing from “what your editors saw while driving into work.” Curious City offered an alternative: ideas generated by “the curiosity and questions of people out there who aren’t just in newsrooms,” she said. “Because there are, for better or for worse, especially in some newsrooms, certain types of newsroom people.”22 She suggested that questions and outreach to expand question-askers would hopefully also help to expand the diversity of voices represented. “I think we can always do better in terms of diversity.”

Story Reporting and Production

Moving on from story selection, the actual reporting phase of Curious City stories varied based upon both question and question-asker. In general, the staff sought to involve question-askers in the process. At minimum, someone would attempt to call the question-asker to confirm they understood the nuance of what they were hoping to learn, as this reporter detailed:

So even before I start reporting it out, I call the person. And they’re always so thrilled. “Oh my god, you’re getting to my question I submitted three years ago. That’s so great.” Or sometimes it’s a very recent one. . . . What I try to understand from them is if I’m understanding their question properly. And exactly what they what to get out of it. . . . Is this aspect the one’s that more important, or is it this. . . . And then I say, “OK. Now I’m going to do a little reporting, then I’ll get back to you. We’re going to look for opportunities for you to come out with me to do some of this reporting.”23

If the question-asker wished to remain anonymous or lacked the time to participate in interviews or field outings, interaction ended there. However, when possible, the reporter or producer invited the question-asker to join them in interviewing a source or visiting a site. A producer explained why they did this:

She wants to know the answer to this. We can tell her the answer. But how much better than telling her the answer than to bring her with us and let the person who is most qualified talk directly to her? Not only do we want that to happen, but we want the audience to hear that happening.24

The producer explained that Curious City deliberately included interaction between question-askers and sources to create an audio “scene” they hoped made the information easier for listeners to process. Including the question-asker also added to Curious City’s branding and, he hoped, encouraged participation. “I want people to hear that and be like, ‘Look she just asked him a really interesting question. Normally you’d expect the reporter to do that, but that was just someone like me.’”

A number of past question-askers noted that they liked this aesthetic of Curious City stories. While some said available time and resources limited their participation, those who did participate reflected upon the experience favorably:

I went into studio and I was terrified because it was like going into the cool kids’ room. But everybody immediately put me at ease. It was very comfortable. And I forgot we were recording it was so comfortable. They didn’t treat me like an interloper. . . . I was included in the interview the entire time. . . . I felt part of it. It was great.25

Several reporters noted that this interaction with question-askers was one of their favorite parts of reporting Curious City stories: “You might think almost in today’s media world, and with social media, I would wonder if people are still bedazzled by the fact that, ‘Oh, I’m on the radio,’ or whatever. . . . Is it really that big of a deal? For a lot of people it is. . . . They’re excited about the fact that their question is driving the story.’”26

Another reporter explained that the process built in a back and forth with the question-asker. As she did her reporting, she kept the questioner in mind: “I just learned some new things today. And I can’t wait to go back and talk to the question-asker and say, ‘Here’s some things I learned.’”27

The process of integrating residents into reporting created a kind of accountability loop where the reporter or producer could get feedback on how the story was going before it broadcast.

Distribution and Feedback

When it came to the distribution phase of the story cycle, Curious City generally adhered to more traditional norms of how journalistic stories were shared. That is, they were broadcast on the radio, on the station’s website, and via podcast, and then were shared via various social media. According to the editor, Curious City programs had a wide reach compared with other WBEZ content. They were broadcast in multiple times slots, and tended to garner more clicks and shares than other WBEZ stories on average.

But while Curious City’s distribution of stories was successful, it was also relatively conventional in engagement terms. The program occasionally did public events—such as live tapings in front of an audience combined with puppet cinema. It also occasionally followed a story with a live Twitter chat to discuss issues raised with listeners and stakeholders. However, while these mechanisms were effective in connecting to listeners in WBEZ’s core audience, they had little chance of reaching beyond this. The outreach project did not attempt to do a marketing campaign alongside the effort to seek out questions—due to budgetary restrictions. So while residents were told about Curious City, and many shared questions for the initiative, they were not given any information about how they could listen to the program or participate more in the future. Curious City staff noted that several people they met requested something to take away with more information. They suggested that in the future it might be useful to have bookmarks, flyers, or other materials on hand. Similarly, live events and Twitter chats were not marketed in target outreach communities aside from online and on-air announcements for WBEZ listeners.

The engagement gap at this point in the storytelling cycle meant that even if a story covered areas targeted in outreach, discussion or feedback was likely to come from listeners who were generally not from these communities. In the case of many South and West Side communities, this often (but not always) meant white reporters covering communities of color for a majority-white audience. While the issues and perspectives of question-askers from those communities were represented and shared with WBEZ’s audience, there were few opportunities for residents of those communities to participate in dialogues about issues raised, unless question-askers did their own personal outreach (e.g., notifying their own Twitter followers, etc.).

Of course question-askers and audience members did play an active role in circulating and sharing feedback on stories via social media. And some question-askers took additional initiative to do their own outreach independently. One suburban resident and question-asker shared how she had posted her story in a working mom’s group she belonged to. She said it “spurred a crazy discussion and debate. Lots of people saying, ‘This is amazing. I’ve had this question, too.’” She suggested WBEZ would do well to seek more engagement post-broadcast: “There’s a responsibility to not just sort of publish it, and push it, and forget the story, but to engage people more in debate, in conversation,” she said.28 She suggested this engagement could be online, but also face-to-face in things like discussions or roundtables.

Several reporters and producers also suggested they would like to do more regarding outreach and marketing, from more opportunities for public listening sessions to provide feedback, to using WBEZ spaces such as its neighborhood bureaus as engagement hubs. However, most acknowledged that such efforts were currently limited by available resources.

This energy suggests there may be untapped potential to explore by enlisting residents in a more active role at the distribution, discussion, and feedback-end of the story cycle. WBEZ, like many media outlets, stopped allowing listener comments on its website. While some use social media platforms to discuss programs, those who do not partake in social media now have fewer ways to engage in dialogue about programming that has been broadcast. Exploring opportunities at this point in the process could deepen the cycle of engagement overall.

Strengthening the Storytelling Network?

In the early 2000s, a group of University of Southern California researchers led by Dr. Sandra Ball-Rokeach developed what became communication infrastructure theory as a framework to analyze what made urban neighborhoods more or less cohesive and engaged. They identified what they called a “storytelling network”—where local media, community organizations, and residents told and circulated stories about their community and the issues it faced. In areas where this network was stronger, residents tended to have higher levels of civic engagement and a sense of belonging to their community. When this network was fragmented, say by weak ties between community organizations and media or racial/ethnic/linguistic divisions, community cohesion and engagement tended to suffer.

Figure 3. Communication infrastructure theory’s community “storytelling network.” Source: Courtesy of the Metamorphosis Project.30

Curious City’s outreach efforts attempted to build connections with residents, organizations and institutions, and local/ethnic media—all considered actors in the storytelling network. Given this, how did their initiative affect the storytelling network, if at all?

Connecting Residents and Media

As outlined above, the outreach project centered primarily on the link between media and residents. Curious City sought to connect to a more geographically diverse pool of residents to solicit questions. By going out to communities and talking with people face to face, the outreach project connected to residents who had never heard of WBEZ. Many expressed surprise in seeing a producer come to their community to ask them what questions they wanted covered.

“I don’t see people walking through the neighborhood and talking to people,” said one woman in a park in a South Side neighborhood. “Quite honestly, I was like, ‘Why are these white people over here?’”31 However, this surprise quickly shifted to receptivity for her and many others. Much of this had to do with timing. For many, the simple act of showing up on an ordinary day resonated, and contrasted with conceptions of media only swooping in to cover negative events related to crime or violence. One young man advised journalists that “they should be out there keeping with the community.”32 He suggested they would learn more if they could get to know residents as people, and try to make them feel comfortable in their interactions. He contrasted this with the behavior he saw from reporters from local television news: “Instead of coming up, ‘Oh, what happened? What happened?’ Put your microphone down.”

Almost all residents of predominantly African-American South and West Side neighborhoods interviewed expressed a feeling that their community was misrepresented and misunderstood by the media overall. Several, including this resident of the West Side Austin neighborhood, expressed a sense of distrust, particularly regarding how violence is covered:

They’re not here to get the full detail of the story, so they take the story and put it in their own words. So, yeah, they come out, but they come out with a different story. . . . For example, if there’s a shooting and the shooting took place this way, they rewrite it up the way they want to write it up before they get to their next job. It’s all shenanigans.33

Many expressed frustration that their community was always portrayed negatively as “a lost cause.” Several attributed this to an impulse to sensationalize stories for business interests: “Because journalists are just trying to do a story. And you sensationalize, or you know, overlook important things, just to sell. And that’s not fair. Because it’s like a lot of things are going on in the neighborhoods that journalists don’t know about.”34

One resident explained that her relatively quiet and safe neighborhood was often stigmatized by broader negative coverage of the South Side—to the point that she had been woken up at one in the morning by out of town family calling to check on her safety. “I think journalists need to be more responsible, and need to really learn communities,” she said. She also called on residents to “play a bigger role in how their community is represented.”

This resident supplied a question that was eventually reported. She, and others in outreach communities, expressed an appreciation for the opportunity to share their perspectives with media. However, she and others who were not WBEZ listeners also expressed doubt that fellow residents would visit the Curious City website to participate without in-person encounters.

In a few cases, particularly in some of the majority-white suburbs, the outreach participants were already listeners. In these situations, by being invited to share questions, residents became more invested in voicing issues of interest in their community. In these suburban areas, residents were more likely to see their community as under-covered than misrepresented.

Overall, given the lack of marketing to build longer-term, two-way relationships, the outreach effort did more to strengthen the link between media and residents in one direction (from media to residents) than the other (from residents to media).

Connecting Media and Community Organizations

As part of its outreach experiment, Curious City explored partnerships with a range of community organizations, institutions, and businesses. The objective was to connect with these groups as intermediaries that could help with outreach to more residents. While Curious City did not set out to build relationships with these groups for their own sake, it is worth looking at this link between media actors and community groups.

The relationship between media and community organizations is almost always challenging given the different objectives, expectations, and interests of these stakeholders. Journalists broadly seek “stories,” which they hope will also serve the greater good by informing the public. However, the mission of many organizations is to raise awareness of particular community issues, which may or may not have the ingredients required to make a compelling story.

Curious City was not immune to these complications. The project attempted to work with a few different kinds of organizations to help solicit questions from their communities. The journalists expressed an appreciation for the work of community organizations and their awareness of issues facing residents. These groups were embedded in neighborhoods and facilitated connections that could otherwise be challenging for outside journalists coming in to make. “Their mediation is helpful, in that it exposes us to new people,” said Allee.

Community organizations similarly appreciated when media came to them to learn about their community, as a leader of a group in a West Side neighborhood explained:

Community organizations are the lifeblood of what goes on in neighborhoods . . . in the programs or services they offer, the people they employ. . . . The reporters should be going to these organizations, telling the stories of the people they are working with or themselves in order to represent the community.35

The community leader argued that in his community “most of the times, we’re the subject of a story—and it’s not our perspective. Once the lights and camera go off, that reporter is gone.” He appreciated that Curious City attempted to give community members “a voice, even if just on the topics that are being discussed.” He argued that this sort of contact was essential to reporting a fuller representation of the community, saying, “We have a different perspective than a reporter who comes in and who doesn’t live in the community—who’s never been to it—and the only time coming to the West Side is, ‘Oh man, something bad.’ We know about the ‘something bad,’ but we also know about all the good stuff that goes on over here. So it just gives it that different outlook.36

Despite what seemed to be complementary missions, these connections between community groups and media can run into bumps. In the case of Curious City, Allee explained that they had run into difficulties with organizations he perceived as “pushing an agenda” and attempting to “tip the scales in terms of the topics or the content they want out in the world.” For example, a group would help Curious City gather questions from area residents, but most of the questions that then came in were about the topic the organization was involved with:

I got worried they were pushing people to contribute because of their issue. And that’s OK. . . . If it’s on their mind, it’s on their mind. But . . . I want return people, too. I want people to feel comfortable . . . to trust us with all manner of questions about anything that might be in play for them. Not just one thing. I would worry about disappointing them. I’m not going to do fifty questions a year about the same topic.37

Allee said it had been difficult to get some partners on board with the concept of “starting from the individuals’ vantage” and allowing them to ask questions about anything that interested them, even if it was on a less serious and more fanciful topic. For this reason, over the course of the project, Curious City gravitated more toward public libraries. Libraries, he said, had a shared mission of being open to any kind of learning and being there “to satisfy people’s curiosity.”

Visiting one suburban library, the staff member coordinating the partnership with Curious City expressed a similar mission. “What attracts me to the program is to hear what other people are thinking about. And I like the variety,” she said. The library was all about “learning and discovery,” and she thought in addition to getting questions for Curious City, the collaboration could benefit the library’s mission as well. “If our reference staff engages a patron with something they’re interested in—what’s your question for WBEZ? Maybe it’s the Superfund site, right. What resources can they then connect them to here in the library so they can learn more?”38

The library partnership coordinator suggested the collaboration could be even more effective if they customized some of the outreach materials. While WBEZ did not have resources to invest in marketing, she suggested the library could make some of its own signage and flyers in both English and Spanish. “That would go a long way. People trust the library,” she said. “We worked really hard to build a reputation. People come here and they feel safe. For a community that has a significant population of undocumented immigrants, that is really important. So having our name be on there helps with respect to that population.39

In this instance, the library was happy to lend Curious City its credibility, because it furthered a mutually beneficial goal. But the library communications person acknowledged that it faced similar issues to all community organizations navigating relationships with media. She also sought access to media coverage, not for a specific issue, but to raise awareness of the work her library did, such as providing English language and other courses for adults and children. “Whenever one of our stories is featured, and it talks about the impact that it’s having on our community, that helps make the case for why people should donate to us,” she said. So while Curious City looked upon libraries favorably as “value neutral,” and the libraries did not expect coverage to come directly from Curious City, the libraries were not exactly free of any agenda in interacting with a media partner.

The partnerships formed between Curious City and libraries, and a few other organizations, may grow over time into productive, two-way exchanges. With libraries in particular, the Curious City team saw the greatest success when they set up tables outside (weather permitting) or just inside library lobbies. This lent Curious City the credibility of association with a trusted local resource, and the flexibility of being able to encourage question-askers and explain the project. At the same time, residents were able to engage with staff more on their own terms—choosing whether to stop and talk with them on their way in, or out—rather than feeling surprised and sprung upon. Both parties in this partnership expressed sentiments of mutual benefit, suggesting that at least with these particular community institutions, stronger network links were forged.

With other community organizations, however, there was at best a minimal strengthening of storytelling network links. This is unsurprising given an attitude common to many journalists that they must guard against providing “free advertising” for organizations that presumably have financial interests in promoting their agenda. As one participating journalist said, “I don’t see the need to carry water for any particular group.”40 As a result, links between media (Curious City) and organizations were only strengthened in particular instances for particular kinds of community institutions (e.g., libraries).

Connecting to Ethnic and Hyper-Local Media

While it was not a focus of Curious City’s outreach project, the team did also attempt to forge ties with local suburban and ethnic media as a way to both redistribute some of its content and to encourage new groups of residents to participate.

The outreach producer shared his experience trying to partner with a Polish community newspaper to share content. At one point, when he had been waiting for some time with no reply to his query, he expressed concern that the newspaper might not be interested, or worse, that it may have misinterpreted his request: “It might be kind of insulting in some ways. Might be, ‘We’re fabulous, take our great content.’” In the end his worry was misplaced: The paper ran Polish translations of Curious City stories adapted for print along with information for how readers could share questions. But this back and forth illustrated the challenges of establishing relationships of understanding, particularly with smaller partners that may have limited staff and resources.

Similar to how it viewed organizations, here Curious City looked at partnering with suburban media as a means for reaching individual residents who were readers. The link went mostly in one direction, from Curious City to the hyper-local and ethnic media. This is not surprising given the balance of resources and Curious City’s remit. Nevertheless, WBEZ, as a leading local/regional outlet, may benefit from exploring two-way partnerships with smaller neighborhood and suburban outlets. Such experiments are already taking place with other outlets in the region and nationally. As a youth media director on Chicago’s West Side explained, “Those relationships help better tell the stories. Because we know or least we can lead [the larger media partner] in the right direction of where they can go.”41 At a time when outlets, including WBEZ, acknowledge they have more work to do to increase the diversity of their staffing, it is worth exploring collaboration with existing people-of-color-led media outlets, and outlets from majority-white areas that may be more ideologically diverse. Such partnerships may offer pathways to communication resources that could be shared across boundaries of race or politics.

In aggregate, Curious City’s outreach project did have some influence on the local storytelling network. For many communities in the outreach project, the act of showing up and expressing interest in what residents wanted to know was significant given these communities’ histories with the media. However, given the lack of investment in marketing, this link was in one direction. WBEZ was more able to access community members and their stories, but community members overall were no more able to access WBEZ through this initiative. A similar pattern followed regarding links between Curious City and community organizations, and with hyper-local media. Because Curious City prioritized the perspective of individual residents, a different agenda might be able to reconfigure a two-way exchange between stakeholders.

Conclusion

Curious City’s outreach initiative demonstrates the value that in-person, offline contact can add to digital engagement initiatives. Particularly when these are undertaken in partnership with organizations and institutions embedded in communities with established networks of trust, media initiatives can more efficiently connect with residents they may not otherwise reach. This can have a meaningful impact on whose voices are heard in the media and how participating residents view a media outlet—something that is particularly critical in communities that feel neglected or stigmatized by a history of negative media coverage.

Outreach initiatives like Curious City’s respond to calls for media to listen to communities. They also sit alongside recommendations by a previous Tow study on community-based solutions journalism in which residents of stigmatized communities called for more opportunities to connect with media throughout the storytelling process.42 However, these initiatives have potential to go further if they address some key engagement gaps. For example, even a small financial investment would allow future outreach efforts to develop grassroots marketing tools such as flyers or even physical signs. This would increase the chances of engaging residents beyond their asking a single question, possibly even encouraging them to return to the project website to listen, ask more questions, and share and discuss their perspectives on programs heard. Likewise, investing more in post-broadcast activities to promote discussion and dialogue could be made more accessible to residents from these communities. Here, too, digital initiatives can be combined with offline strategies that draw from community organizing practices such as holding stakeholder convenings or creating community coordinating councils.

Hearken’s founder Jennifer Brandel explained that she and her team regularly encouraged members of their network to pursue online and offline engagement:

You know a lot of newsrooms will see our approach, see our format, and say, “Oh, can we just take the questions and do them?” I’m like, ‘You can, but you’re actually losing out on a lot of relationship building.’’ . . . That would be very extractive to just take their questions. Never follow up with them. Never tell them that you answered it. Never mention them in the final pieces that you’re doing. Never give them credit.43

She acknowledged that Hearken could not control how newsrooms use its technical platform, but that it has put forward a model of best practice. She explained that ideally she would like engagement throughout the story cycle, extending beyond a story’s broadcast. “Afterwards, depending on what the story was about and who it served, figure out a way of extending that into the communities who would be the most interested or who would have the most to gain,” she suggested. Brandel shared her own experience from the early days of Curious City, when they organized in-community events to follow up on issues in partnership with local organizations. She argued that they connected residents who otherwise would have lacked the opportunity to get to know each other, while giving stakeholders a chance to follow up on issues in a way that might not be appropriate for a news organization.

Developing meaningful partnerships with community organizations and institutions takes a substantial time investment. This includes coming to common understandings of expectations and goals, and seeking ways that both partners can benefit. Because Curious City had limited time to invest and was focused on individual residents more than institutional ties, this was not generally possible during the scope of this outreach project. However, to make relationships with institutions such as libraries sustainable and productive over time, it may be worth investing in managing these relationships in a way that more directly engages the interest of the partner organization. Openly acknowledging the interests of actors and finding ways to balance them may be more realistic than pursuing partners that have “no agenda.” This sort of transparency may make it possible to broaden the pool of partners to include other community organizations as well. Similarly, cultivating partnerships with hyper-local/ethnic media outlets and youth media programs requires considerable time. However, the potential benefits could allow Curious City/WBEZ or other outlets to engage with community voices in a way that encourages conversation and avoids extraction.

Overall, journalists, residents, and community stakeholders were favorable about Curious City’s more engaged process and how it challenged some traditional journalistic practices. However, many also expressed that it was a way of working that had a time and place: “It would be weird to have a radio station or newspaper totally driven by, ‘Here’s what people told us to write this week,’” said one reporter. 44 Another journalist shared thoughts on why there should be limits: “Do I think we should live in a world where all news is started by the audience? No. I like the idea that there are journalists who help set priorities. And beat reporters whose continued doggedness on a particular area elicits new questions that we never knew we had. . . . I think too much of it, too much of anything . . . is not a good thing.”45

Several Curious City question-askers from WBEZ stronghold areas were relatively conservative about the role non-professionals should play in making media, expressing a reluctance to get information from blogs and a preference for reading the work of professional journalists. “I appreciate the fact that they do programming based on their audiences’ interests,” said a question-asker. “But I also think they need to tell stuff that we may not know we need to know.”46 Several of these residents spoke of Curious City as filling a supplemental role in their media diet. Many said they valued Curious City for its “quirky” stories, and saw it as an antidote to otherwise depressing news fare. In contrast to many residents from Curious City’s outreach areas, these participants expressed trust in professional media coverage and were overall more satisfied with how their communities were portrayed by media.

Nevertheless, some question-askers and journalists pointed to a critical need to question the status quo. Pointing to media coverage of the 2016 elections, one journalist critiqued the “stranglehold” the national press had on “what gets put forth in the national conversation,” saying: “I just think you listen to what people’s priorities are in their lives and what they’re interested in, and then you listen to what is on CNN all day—and it’s a disconnect.”47

By actively seeking out questions from new geographies and communities, Curious City’s outreach went some way in expanding engagement in the cycle of storytelling—and, at least in a limited way, strengthening links in the local communication infrastructural “storytelling network.” The program could go further in challenging historic power dynamics between media and underrepresented communities by investing more in mutually beneficial partnerships and post-broadcast dialogue, as well as engagement that contributes to a feedback loop.

If the media seeks to alter gaps between media makers and communities, it will be well served to consider how a potential listener, reader, or viewer is situated within online and offline community networks rather than focusing exclusively on individuals. The people formerly known as the audience don’t simply listen to or read stories. They discuss them with friends. They argue about them with family. They refer a neighbor to check out a website or a post on a fellow friend’s Facebook page. They may even mention a story at a community meeting. Engaging with residents requires meeting them in the environments they inhabit, both online and offline. It is a messy and time-consuming business. But if media makers are to take steps to repair fractured trust with the publics they seek to serve, they may well need to undertake radical listening, and grapple with how they can create spaces not just to give voice, but to facilitate dialogue between voices.

Acknowledgments

Many thanks to the Tow Center for Digital Journalism—and, in particular, Elizabeth Hansen, Nausicaa Renner, and Claire Wardle—for their support and thoughtful feedback. The project would not have been possible without the participation of WBEZ’s Curious City project. Despite hectic schedules and workflows, staff and freelancers generously allowed me to shadow them as they went about their work and outreach efforts. Thanks also to the journalists, listeners, and community members who participated in interviews. Be they at a newsroom, library, park bench, or bus stop—all were open and reflective, offering a range of candid insights on how media engages with the public from their various vantages. A special thanks to Jennifer Brandel for openly sharing thoughtful perspective on Hearken and beyond. I would also like to recognize the many people who have formally and informally helped me think through how this project sits within the larger world of journalism engagement and communication infrastructures, especially Dr. Sandra Ball-Rokeach, Daniela Gerson, and Jacob Nelson. —May 2017

Citations

- “What Is Social Journalism,” Tow-Knight Center for Entrepreneurial

- “What Is Social Journalism,” Tow-Knight Center for EntrepreneurialJournalism, https://towknight.org/research/social-journalism-who-what-when-how/what-is-social-journalism/.

- Jay Rosen, “The People Formerly Known as the Audience,” PressThink,2006, https://archive.pressthink.org/2006/06/27/ppl_frmr.html.

- Daniela Gerson et al., “From Audience to Reporter: Recruiting and TrainingCommunity Members at a Participatory News Site Serving a Multiethnic City,”Journalism Practice, nos. 2–3 (2017), 336–354.

- Melissa Wall, “Citizen Journalism,” Digital Journalism, no. 6 (2015), 797–813.

- Jay Rosen, “The People Formerly Known as the Audience,” PressThink,2006, https://archive.pressthink.org/2006/06/27/ppl_frmr.html.

- Hearken, https://www.wearehearken.com.

- Andrea Wenzel, Interview with Shawn Albee, 2016.

- WBEZ Curious City, https://curiouscity.wbez.org.

- “How Can Curious City Diversify the Pool of People Who Ask Ques-tions?” WBEZ Curious City, 2016, https://wbezcuriouscity.tumblr.com/post/140362287302/how-can-curious-city-diversify-the-pool-of-people.

- WBEZ Curious City, “Curious City McCormick White Paper,” WBEZ,2017, https://docs.google.com/document/d/1s1xgcneTlmMJKk5aq-b9Z3XL3bRItr-_jnFE-xoIjvc/pub#id.6jpkqy6p0cey.

- Andrea Wenzel, Interview with Shawn Albee, 2016.

- Ibid.

- Andrea Wenzel, Interview with Journalist 5, 2016.

- Ibid.

- Andrea Wenzel, Interview with Journalist 2, 2016.

- Andrea Wenzel, Interview with Shawn Albee, 2016.

- Andrea Wenzel, Interview with Journalist 5, 2016.

- Andrea Wenzel, Interview with Journalist 4, 2016.

- Andrea Wenzel, Interview with Journalist 3, 2016.

- Andrea Wenzel, Interview with Journalist 2, 2016.

- Ibid.

- Andrea Wenzel, Interview with Journalist 3, 2016.

- Andrea Wenzel, Interview with Question-Asker 2, 2016.

- Andrea Wenzel, Interview with Journalist 4, 2016.

- Andrea Wenzel, Interview with Journalist 2, 2016.

- Andrea Wenzel, Interview with Question-Asker 5, 2016.

- Metamorphosis, https://www.metamorph.org/research/theory/.

- Andrea Wenzel, Interview with Outreach Resident 1, 2016.

- Andrea Wenzel, Interview with Outreach Resident 5, 2016.

- Andrea Wenzel, Interview with Outreach Resident 10, 2016.

- Andrea Wenzel, Interview with Outreach Resident 1, 2016.

- Andrea Wenzel, Interview with a community group leader, 2016.

- Ibid.

- Andrea Wenzel, Interview with Shawn Albee, 2016.

- Andrea Wenzel, Interview with a library staffer, 2016.

- Ibid.

- Andrea Wenzel, Interview with Journalist 5, 2016.

- Andrea Wenzel, Interview with a community group leader, 2016.

- Andrea Wenzel, Daniella Gerson, and Evelyn Moreno, “Engaging Commu-nities Through Solutions Journalism,” Tow Center for Digital Journalism, 2016,https://www.gitbook.com/book/towcenter/solutions-journalism/details.

- Andrea Wenzel, Interview with Jennifer Brandel, 2017.

- Andrea Wenzel, Interview with Journalist 4, 2016.

- Andrea Wenzel, Interview with Journalist 5, 2016.

- Andrea Wenzel, Interview with Question-Asker 4, 2016.

- Andrea Wenzel, Interview with Journalist 5, 2016.

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.