Executive summary

In 2018, the technology reporter Taylor Lorenz predicted journalists would adopt influencer tactics to grow their own audiences and directly distribute content to their followers. Since then, journalists have continued to experiment with using digital platforms as part of their career activities. These digital tools provide journalists with the opportunity to capitalize on and monetize their personal brands and skills. In 2020, Lorenz followed up her prediction, anticipating that we will now begin to see “the dark side of this movement.” While independence provides journalists with new career opportunities, it also presents challenges as they risk burnout, precarity, audience pressures, and backlash for their independent work.

The media is often studied as either institutional news work or social media activity. However, on digital platforms journalists increasingly blur the lines between personal and professional, institutional and independent, and reporting and commentary. Opportunities to monetize online content, connect with new audiences, and pursue creative and multimedia projects expand the ways in which journalists can piece together their careers.

Thus, questions arise about how journalists structure and conceptualize their work when working on digital platforms. Why and how do journalists use these tools? What do journalists see as the tools’ strengths and weaknesses, and how do they fit into the broader media ecosystem? In what ways do they complement or contradict journalistic norms and standards?

This report draws on a case study of journalists who use the digital newsletter platform Substack to understand how such platforms affect their work, careers, and identities. Through a combination of computational and qualitative methods, I seek to understand who uses Substack, why journalists use the platform, how they use it, and how Substack relates to the broader media ecosystem.

I identify three dominant themes that explain how journalists use and interpret Substack. Each theme carries implications for how journalists structure their careers, produce media content, and conceptualize their identity.

- Journalists who view newsletters as a career resource use Substack to enhance their work within the traditional legacy media industry. They use their newsletters to create a persona as an expert on a niche topic, publicize their work, practice professional skills, and build a loyal audience in hopes of achieving career advancements. Most in this group tend to offer their newsletters for free; however, some who view themselves as experts in the topics on which they write charge a subscription fee. They seek to continue to uphold journalistic norms of objectivity, fairness, and balance even when embracing the freedom of work on digital platforms. In this way, these writers rely on ties with institutional media outlets to which they seek to link their careers. Strong ties to the media industry and value of journalistic norms strengthen their identification as journalists as a core aspect of their sense of self.

- Alternatively, some pursue newsletters as an alternative media model. These journalists critique dominant media outlets, highlighting experiences of precarity, inefficiencies, and the ways in which norms of objectivity exclude personalized forms of information production and audience engagement. Within their newsletters, these writers strive to produce alternative stories that they feel dominant media institutions do not support or incentivize. Paid subscription models offer a new funding stream that grants writers independence to capitalize on their positionality and personal experiences as a legitimate source of content production. Thus, these journalists express broadened conceptions of their professional identity defined by innate qualities and skills as they seek to build careers unconstrained by institutional norms and barriers.

- Finally, a third subset of journalists define their newsletters as a lifeboat. For these journalists, newsletters serve as stopgaps when they lack other career opportunities and resources. These journalists are critical of the economic feasibility, informational quality, and role of technology companies in newsletter media models. In this way, they remain skeptical of Substack and do not plan to use the platform for a prolonged period. Feelings of hopelessness with the media industry led these writers to distance themselves from their professional identity as journalists.

These three themes illustrate how digital tools expand the ways in which journalists pursue careers and conceptualize their work. By highlighting the multiple ways in which a digital platform affects the careers and structure of journalism, the report emphasizes the ambiguous implications of technological change, rather than representing it as predetermining changes or affecting those who use digital tools all in the same way.1Lee, Kevin Woojin, and Elizabeth Anne Watkins, “From Performativity to Performances: Reconsidering Platforms’ Production of the Future of Work, Organizing, and Society.” Sociologica 14(3), 205-15. https://doi.org/10.6092/issn.1971-8853/11673 The report concludes with a discussion of the implications of the diverse uses of digital platforms for journalists on the trustworthiness and consistency of information in the public sphere.

Introduction

Ben started writing about hip-hop as a freelance journalist in 2014. He gradually built up connections with major outlets, producing articles picked up by business and culture magazines. However, Ben felt dissatisfied by the transactional nature of his work. “It didn’t really feel like I was making a true impact beyond getting an occasional check,” he explains. Ben wanted to make more of an impact with his writing. He wanted to build a relationship with his readers, rather than “writing for the editors” to make a living.

In 2017, Ben started an email newsletter focused on the artists, producers, and fans innovating the business of hip-hop. The newsletter allowed him to build an ongoing and direct relationship with his readers and capitalize on his expertise in his niche topic.

He describes his motivation to start the newsletter:

It was the opportunity to take advantage of the changing landscape in digital media, but also have an opportunity to elevate and have a proper home for the type of things that I was writing.… I saw what a few other early writers were doing in this space, where they were taking advantage of the tools and the platforms to create a home for their writing, and in many ways, being able to build a sustainable career and enterprise off that. It was taking advantage of the niche economics that I think are possible with the internet today, where because of how cheap it can be to get something started, you don’t necessarily need to have a vast user base. You can have a publication that appeals to a pretty small base, but a passionate base of readers, and then just build a business model around that.

Ben’s newsletter has grown into his full-time occupation, with more than ten thousand paying subscribers. He expresses pride in the entrepreneurialism of his pursuits and hopes to see “more independent media own their particular niches,” through which writers can “succeed to do what they want to do full-time.”

Ben’s story exemplifies how digital technologies are creating opportunities for journalists and information producers to structure their careers to produce and distribute content in new ways. Traditionally, dominant professional institutions—most notably legacy media publications and more recently digital news outlets—structured journalistic norms and dictated career success. These institutions served as gatekeepers that enabled insular professional groups to maintain control over the production and distribution of legitimate knowledge and information.2Karin Wahl-Jorgensen and Thomas Hanitzsch, eds., The Handbook of Journalism Studies, International Communication Association (ICA) Handbook Series (New York: Routledge, 2009). They promoted techniques, such as the norms of reporting, sourcing, and fact-checking, as methods of producing “objective” information.3 Michael Schudson, Discovering the News (New York: Basic Books, 1981). Additionally, through the creation of explicitly professional spaces and publications, they intended to separate journalists’ professional roles as revealers or communicators of external facts from their private roles as subjective individuals with their own worldviews and values.

In contemporary media work, digital technologies and online platforms allow journalists to use a variety of tools to produce and distribute content. Digital tools offer journalists new opportunities and constraints. Online platforms challenge the clear boundaries between professional and personal forms of content production.4Erin Reid and Lakshmi Ramarajan, “Seeking Purity, Avoiding Pollution: Strategies for Moral Career Building,” Organization Science, November 24, 2021, orsc.2021.1514, https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.2021.1514. Furthermore, digital platforms, direct distribution channels, and diverse forms of information communication—podcasts, liveblogs, newsletters, etc.—blur the line between professional journalism and the increase of other types of digital creatives and content producers.5 Emily Bell and Taylor Owen, “The Platform Press: How Silicon Valley reengineered journalism” (Columbia Journalism Review, 2017). Digital tools thus require journalists to combine networks and strategies from professional journalism with entrepreneurship, microcelebrity, influencer culture, research, and academia. Additionally, digitization creates new incentives for news work and ways of defining success, including a focus on audience engagement, circulation metrics, and digital attention.6Angele Christin, Metrics at Work (Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 2020); Caitlin Petre, “The Traffic Factories: Metrics at Chartbeat, Gawker Media, and The New York Times,” Tow Center for Digital Journalism. A Tow/Knight Report (Columbia School of Journalism, 2015); Rebecca Jablonsky, Tero Karppi, and Nick Seaver, “Introduction: Shifting Attention,” Science, Technology, & Human Values, November 22, 2021, 016224392110588, https://doi.org/10.1177/01622439211058823. Last, as journalists engage in independent forms of online content production, technology companies serve an increasingly central role in structuring how journalists produce—and audiences access—news and information.7Matt Carlson, “Automating Judgment? Algorithmic Judgment, News Knowledge, and Journalistic Professionalism,” New Media, 2017, 18. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F1461444817706684

Simultaneously, journalists face challenges in legacy media work due to increasing employment precarity and distrust of mainstream institutions. Dominant media outlets increasingly favor part-time, contingent, or contract-based work.8Chadha, Kalyani, and Linda Steiner, eds. Newswork and Precarity. London; New York: Routledge, 2022.; Cohen, Nicole S. “Entrepreneurial Journalism and the Precarious State of Media Work.” South Atlantic Quarterly 114, no. 3 (July 2015): 513–33.; Vallas, Steven P., and Angèle Christin. “Work and Identity in an Era of Precarious Employment: How Workers Respond to ‘Personal Branding’ Discourse.” Work and Occupations 45, no. 1 (February 2018): 3–37. https://doi.org/10.1177/0730888417735662 In 2021, the Pew Research Center reported that newsroom employment has fallen 26 percent since 2008.9Mason Walker, “U.S. newsroom employment has fallen 26% since 2008,” Pew Research Center , July 23, 2021/. Employment precarity incentivizes or necessitates journalists to seek alternative career opportunities, such as using digital platforms. Additionally, Americans remain skeptical about journalists’ and media companies’ ability to communicate quality information. The percentage of Americans who say they have a great deal or a fair amount of trust in the mass mainstream media fell from 53 percent to 40 percent between 2002 and 2020, according to a Gallup poll.10Megan Brenan, “Americans Remain Distrustful of Mass Media,” Gallup.com, September 30, 2020. That distrust contributes to news consumers seeking alternative sources of content outside of standard outlets and publications.

This report focuses on journalists who write independent email newsletters on Substack within the context of the changing status and role of legacy and digital news work. I draw on fifty-two interviews with journalists who write email newsletters to offer a content analysis of their professional backgrounds and newsletter texts. I focus on how the prevalence of platform technologies and the changing role of media institutions affect the ways in which journalists navigate career opportunities, conceptualize their goals, produce content for their audiences, and define their professional identities. This includes understanding journalists’ motivation for working on digital platforms: how they distinguish career transition points and define success, produce content, perceive their audience and networks, and incorporate digital tools into their careers.

The report proceeds in three additional sections. In section one, I describe the Substack case study and outline my research methodology. Section two presents the findings of the report in two subsections. First, I use computational data to explore newsletter writers on the platform and the network structure of newsletter content. I then use my core findings to draw on qualitative data to discuss three dominant themes that emerged from my interviews and explain how interviewees use and understand Substack: using newsletters as a (i) career resource, (ii) alternative media model, or (iii) lifeboat. Each of these themes relates to distinct goals, strategies for content production, and conceptions of professional identity. Finally, the report concludes with a discussion about how the varied ways in which journalists approach and interpret newsletter production relate to phenomena such as the crises of expertise, informational distrust, and post-truth politics.

Case Study and Method

Substack

This report focuses on journalists who use or have used the newsletter platform Substack. Focusing on a single platform allows comparisons of how journalists use the same digital tool.

Substack started in 2017 as an alternative media space in reaction to critiques of institutional and social media production. The company provides the infrastructure to write and distribute digital newsletters, giving creators control over their email subscription lists, archives, and intellectual property. Substack also focuses on writing as the main output versus requiring other technical or digital skills. The company targets journalists, writers, experts, and visual-content creators geared toward discursive output, although it has been expanding its focus and functionality. Journalists who use Substack largely do so for the purpose of sharing and producing textual information.

Substack was created by media insiders with the goal of using technology and entrepreneurship to help independent writers make a living by providing a direct distribution and subscription product. In doing so, Substack seeks to present an alternative to ad-supported media. The company contrasts its platform with those of advertisement-based media models that offer incentives toward shallow “clickbait” and “fake news.” Instead, Substack frames itself as a resource for free speech, “democratizing” discourse and producing “personal” and “trustworthy” content. Substack describes itself as a “platform” that “enables” content without dictating it, in contrast to a “publisher” that maintains content moderation discretion. However, the company has attracted controversy due to questions about content moderation and responsibility and accountability for discourse that is produced and distributed using the platform.11Pompeo, Joe. “‘There Has to Be a Line’: Substack’s Founders Dive Headfirst Into the Culture Wars.” Vanity Fair, May 23, 2022; Navlakha, Meera. “Why Substack Creators Are Leaving the Platform, Again.” Mashable, March 9, 2022; Schulz, Jacob. “Substack’s Curious Views on Content Moderation.” Lawfare, January 4, 2021. In response to criticism over free speech and writer precarity, the company has added new features for its users, such as access to legal advice, writer office hours, and community-building resources.

As of 2021, Substack reported millions of users and more than a million paying subscribers.12Tiffany Hsu, “Substack’s Growth Spurt Brings Growing Pains,” The New York Times, April 13, 2022. Its top ten writers reportedly earn more than $7 million in annual revenue. The company is a venture-backed startup. Additionally, the company typically takes 10 percent of paid subscription fees, which range from approximately $5 to $50 per month but are not required. The most popular writers on Substack can make six-figure salaries and more yearly income than in standard media jobs; however, some writers often do not consider newsletter writing as a form of full-time work and thus may balance it with other professional commitments.13Chang, Clio. “The Substackerati.” Columbia Journalism Review, Winter 2020. Given its semiprofessional nature, Substack provides an ideal case study to understand how new career resources offered on digital platforms affect the goals, strategies, and identities of journalists.

Data

The report includes computational and qualitative data to assess journalists on Substack. Computational data include large-scale queries of information drawn directly from the platform, such as writer topics, professional backgrounds, and network patterns. These data provide an overview of who uses the platform and the subjects they cover to help inform the subsequent thematic analysis.

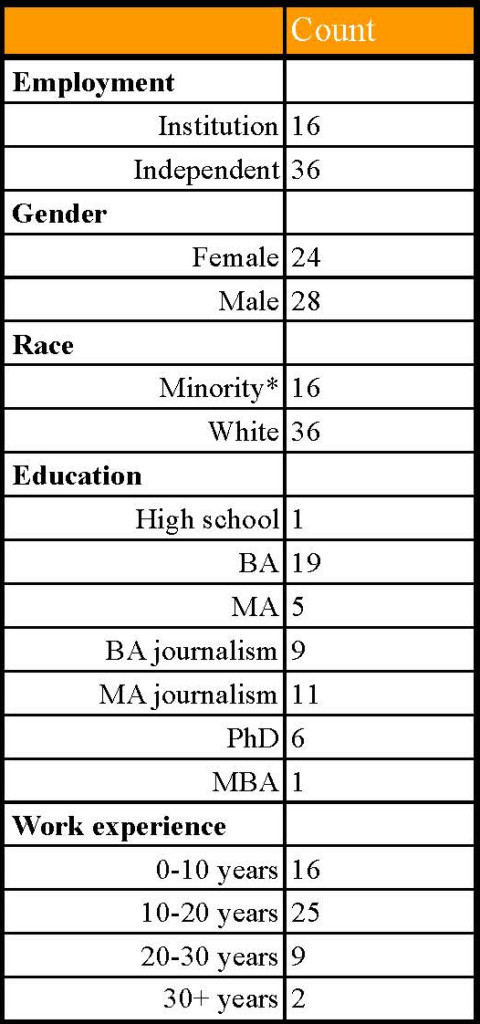

The report’s core findings are based on qualitative data from interviews with fifty-two journalists who write digital newsletters; analysis of their newsletter content, particularly About pages and initial posts that describe their newsletter’s content, purpose, and structure; and online information on their professional background, such as their LinkedIn page, Muck Rack profile, or personal website. Interview subjects were recruited from multiple points of contact to reflect a range of journalists using the platform. (See appendix A for descriptive statistics.)14The sample includes six writers who used Substack but switched to producing a digital newsletter on another platform. There was no discernible difference between the justifications for and use of Substack in this subset of interviewees and the larger sample.

Initial respondents were identified using searches on Google and Substack. Additional respondents were recruited using snowball sampling. Respondents were identified as journalists based on how they self-describe in their newsletter profile, or by using information about their broader professional background available online. The sample captures journalists with a variety of careers that include both independent and institutional forms of work.15 Media ecosystems have also been shown to have a relationship to partisan identity (see Benkler, Faris, and Roberts 2018; Hemmer 2016; Lemieux and Schmalzbauer 2000; Nadler, Bauer, and Konieczna 2020). The study includes participants with a range of political viewpoints, but did not create a representative sample based on partisanship.

Professionals most strongly associated with institutions are employed by a news media company and receive a sustainable salary from their place of employment. In contrast, independent workers take on freelance work with no primary employer and/or self-describe as “independent.” Interview questions were focused on the subject’s professional life, including how they go about their work, balance professional opportunities, and describe their goals and objectives. The research uses qualitative data to illuminate the ways in which digital platforms affect the practices and understandings of journalists, but does not provide a representative or generalizable sample. Textual data, including the About pages of each newsletter and the LinkedIn, Muck Rack, or personal website of interview respondents, supplement interview data to understand respondents’ backgrounds and trajectories. Conclusions are based on how interviewees describe the goals, content, and motivations for their newsletter connected to the structure of their careers and professional identities.

Findings

The findings proceed in two subsections. First, the report draws on computational data to generate a layout of the Substack platform. The computational data provide a map of what topics newsletter writers focus on, what types of writers use the tool, and how their newsletters fit within the broader media landscape. The report then draws on qualitative interview and content analysis data focused specifically on how and why these journalists use Substack.

A Computational Layout: Writers on Substack

Using computational methods, a co-researcher, Nick Hagar, and I explore the types of writers and content available on Substack.16I would like to thank Nick Hagar for his assistance with computational models and analysis. Substack maintains a discovery feature that sorts newsletters by category. When this research was collected in 2021, it maintained nineteen topical categories and has since added six more. Using the search feature, we approximated the landscape of the most active newsletters on the platform and their categorical labels.17The newsletters that are not captured by category search appear far less active: a median of 7 total newsletter posts for general search results, compared with 42 for category search results. Newsletters sorted by category posted a median of 3 days ago, whereas in the general search sample newsletters posted a median of 58 days ago. Thus, Substack’s taxonomy offers a good representation of active newsletters on the platform. Augmenting this approach with other search functions returns small and abandoned newsletters.

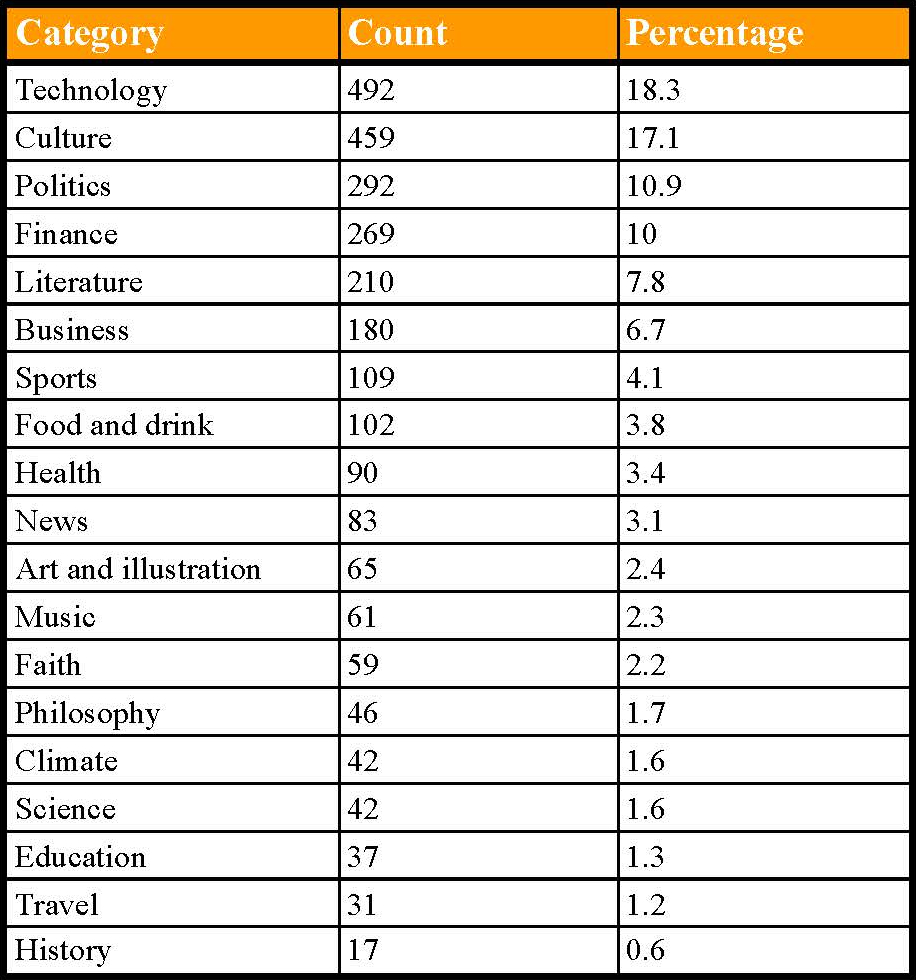

Table 1 provides an overview of how many active newsletters appear within each category through the Substack search function. At the time of our research our analysis identified 2,686 unique active newsletters, a breakdown of which is presented in Table 1.

Unsurprisingly, most Substack newsletters focus on broad and standard categories of media production, such as culture and politics. After 2021, the introduction of new categories of music, comics, crypto, parenting, fiction, and podcasts shows that niche sections of the platform are growing. Additionally, the prevalence of technology as the most active category points to the types of stories and topics most accessible as an independent media source. Writing about technology needs only a computer and internet connection, meaning it requires fewer resources than field reporting. Later in the report, journalists discuss their ability to establish their expertise writing about digital media, making it a lucrative category for newsletter production.

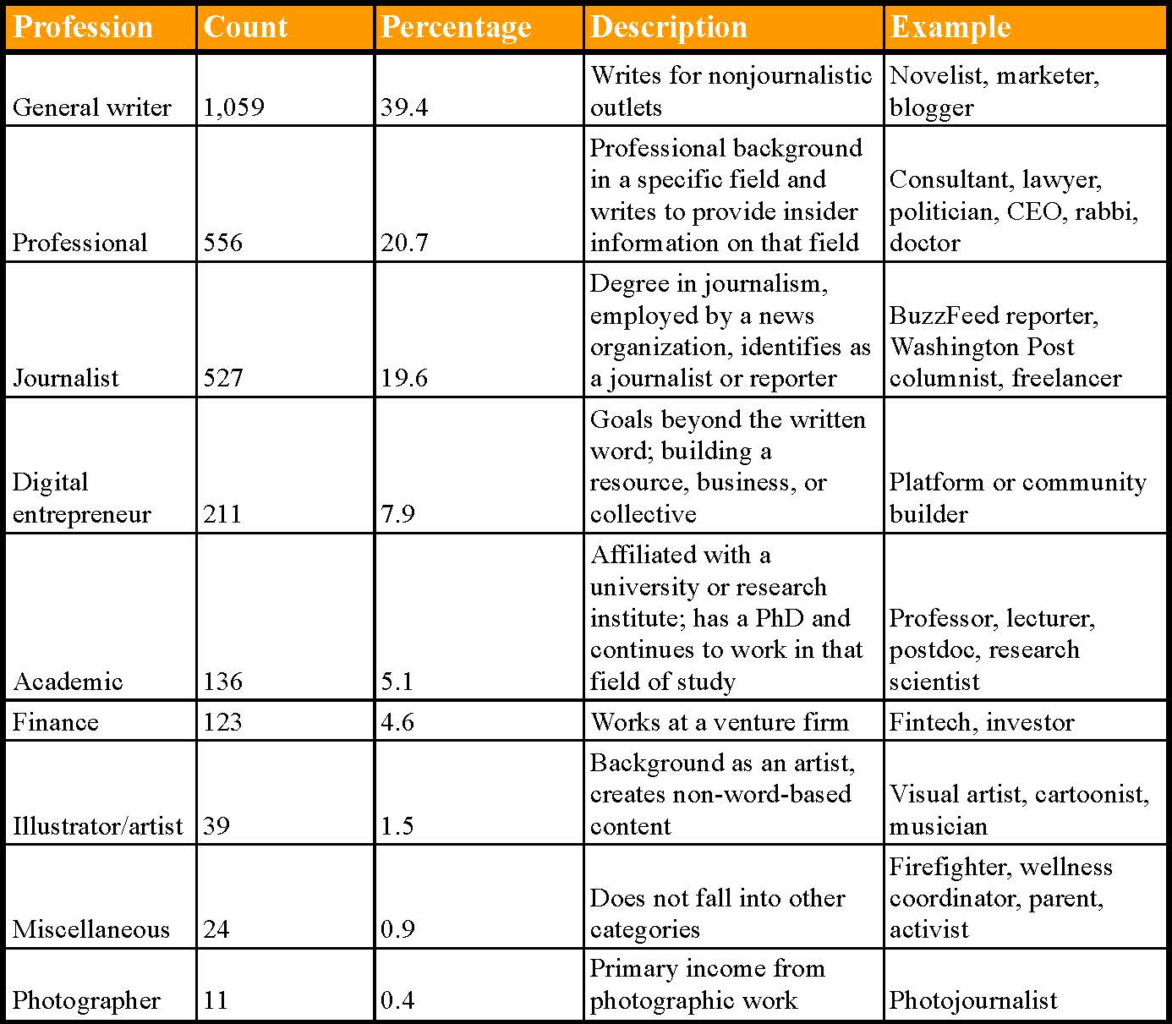

We manually classified the 2,686 active newsletters to understand the professional background of the authors on the platform. Information on authors’ professional background was gleaned from writer biographies, as well as general information available on the Web.

Table 2 represents the background classifications based on the nine most common professional backgrounds found on Substack.

Table 2: Substack user professional backgrounds. Percentages are rounded to nearest one-tenth of a percent.

Once again unsurprisingly, writers and discursive content creators made up most newsletter producers, as well as professionals who use newsletters to capitalize on and share specific expertise. The data suggest that journalists account for about 20 percent of content producers on Substack.

Last, we looked at the relationship between newsletters and other forms of media by comparing hyperlinking citation patterns. We include newsletters that published more than one public post between 2020 and 2021, published posts at a cadence of at least one every thirty days, and published at least one post that included a hyperlink to another webpage (all newsletters in our sample met these criteria). We were only able to access free posts, so our sample does not include paywalled content. This produced a sample of approximately 1.1 million hyperlinks across 139,353 posts from 2,553 active newsletters.

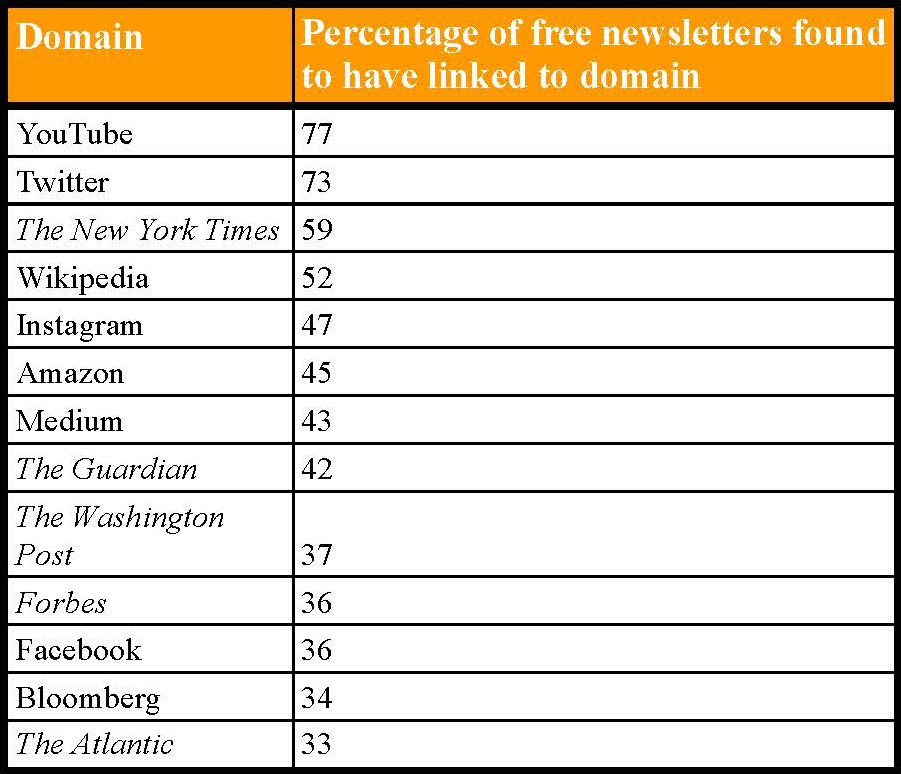

The results show that writers most commonly cite major media and platform domains such as Twitter, YouTube, and the New York Times (Table 3). For example, 77 percent of newsletter writers in the sample have linked to YouTube, and 5 percent of writers have linked to the New York Times. Furthermore, while there is large overlap in linking domains, at most, the same unique URL appears in only 2 percent of newsletters. The infrequency with which newsletters link to one another or to the same news story highlights the siloed nature of newsletter production on Substack. Rather than structurally representing an alternative media environment, writers arguably show a strong reliance on institutional news and established platforms.

Hyperlinking patterns in newsletters match the broader structure of digital attention and influence on the Web, relying on common platforms and domains that are viewed as legitimate, relevant, and likely to generate attention.18Lasorsa, Dominic L., Seth C. Lewis, and Avery E. Holton. “Normalizing Twitter: Journalism Practice in an Emerging Communication Space.” Journalism Studies 13, no. 1 (February 2012): 19–36, https://hdl.handle.net/11299/123293; Messner, Marcus, and Marcia Watson Distaso. “The Source Cycle: How Traditional Media and Weblogs Use Each Other as Sources.” Journalism Studies 9, no. 3 (June 2008): 447–63, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/259563188_The_source_cycle_How_traditional_media_and_weblogs_use_each_other_as_sources; Noam, Eli M. Media Ownership and Concentration in America. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press, 2009; Usher, Nikki, and Yee Man Margaret Ng. “Sharing Knowledge and ‘Microbubbles’: Epistemic Communities and Insularity in US Political Journalism.” Social Media + Society 6, no. 2 (April 2020), https://doi.org/10.1177%2F2056305120926639. Thus, these results indicate that newsletters may be framed as an alternative or independent career resource, but are highly referential to and dependent on dominant media and technology platforms and publications. In this way, digital newsletters represent an element of an integrated and interdependent media environment that journalists must navigate to build their careers.

Journalists’ uses and interpretations of Substack

Analysis of the qualitative data reveals three dominant themes in interviewees’ rationales for starting and maintaining Substack newsletters. Journalists I interviewed engage with and understand Substack as a (i) journalistic resource, (ii) alternative media model, or (iii) career lifeboat. Each use corresponds with different career goals, strategies of content production, and conceptions of professional identity.

Newsletters as a Journalistic Resource

Interviewees who use their digital newsletters as a career resource describe the ways in which they offer an outlet to establish a specialized portfolio, house a holistic body of work, practice the craft of writing, and secure additional career opportunities. One national political reporter describes how advice from a veteran journalist whom she admires to “build your quote-unquote personal brand and make a name for yourself” inspired her to start a newsletter. Such journalists saw newsletters as helpful in achieving career transitions.

An early-career journalist who works for a digital outlet started a newsletter in hopes of acquiring a book deal:

I wanted to write a book proposal…but I didn’t have a body of writing on [the topic].… Once it became clear that I was not going to be able to build out the bulk of that body of writing at my current job, I started looking for a new job, and I started working on this Substack, which I also hope gets me a new job at some point down the line. I think that [it is helpful] if I have something I can point to, to prove I can write about this, people are interested in it, and react to it when I write about it, and you can read it all in one place.

By housing a body of work on the specialization she desires to write about, this journalist’s newsletter serves as a resource to showcase her ability to write, report, and think critically about that topic.

Journalists in this subset thought newsletters were particularly advantageous to build a specialization and gain credibility on niche topics. While they could not always control the topics they wrote about for institutional publications, they could tailor their newsletters to their interests and hopes for their future careers.

Another early-career journalist describes how he uses his newsletter to build credibility writing about the media:

I knew that I needed to establish an authority in this field and the process of writing something every week and being in conversation with other people and reading all the time. It’s a really virtuous cycle in the sense that by doing it, I make other people aware of me and my thoughts and my credibility.

The newsletter helps him maintain a schedule and structure. He advertises the success of his newsletter by listing major institutional news outlets that have cited his work, such as Vox, Nieman Lab, and Poynter. In this way, his newsletter serves as a tool to connect him with major outlets and media figures that model his career goals, using Substack as a career resource to build expertise and connections.

This subset of journalists also sees Substack as a resource to practice and experiment with writing. Many interviewees mention writing as one of their favorite aspects of their career, but lament barriers to writing on the job.

A journalist recently employed as a breaking news reporter describes frustrations that detract from her enjoyment of the work:

As a writer, it’s hard. You want to do your thing, to be reporting and writing, but there’s all these barriers. You can’t get a job. You can’t get paid. You might be sending lots of freelance pitches, but editors are just saying “No, no, no.” It feels like you can never just get the work done. This was a great opportunity for me to start doing the creative work and thinking and hold myself to my journalistic standards and practices.

She describes her newsletter as her “passion project,” to “report it out for myself to have the learning experience, to write about it, and really think about something on a little bit of a higher level than in my day-to-day breaking news role.”

Other interviewees similarly describe their newsletters as outlets for “creativity,” a tool for “professional development,” or a “learning experience.” In this way, these journalists use their newsletters as an outlet to indulge aspects of their career that they feel are unfulfilled in other jobs. Newsletters also allow journalists to deepen skills central to their careers, such as writing, reporting, and critical thinking.

Most interviewees who use their newsletters as a professional resource offer free subscriptions. These journalists believe that keeping their newsletters free allows more readers to access their content and helps them publicize their work. As one interviewee describes: “Sneaking in my stories throughout my newsletter on Substack has been a really great way to get that into people’s inboxes and actually clicked on.” However, a few journalists who said they use the newsletter as a career resource do charge subscription fees. They view themselves as established experts on the topics that they write about, rather than using the newsletter as a resource to build expertise.

An editorial director at a business and culture magazine describes her expertise based on her extensive work experience of more than a decade in multiple newsroom roles. Her newsletter, focused on the craft of journalism, has a monthly subscription fee. She decided to paywall the content because she “was putting time and effort into it” and “thought it was worth something.”

Many journalists who consider themselves experts write on the media, news industry, and digital culture in their newsletters. In this way, the structure of journalistic work using digital tools creates opportunities for journalists to specialize and write about their experiences and knowledge of media and internet trends.

Journalists using their newsletters as a career resource balance personalization and professional norms within their content. One journalist who specializes in audience engagement and new-media innovation notes that “keeping that personal note is really important,” especially to connect with and build a loyal audience.

Another journalist, who writes about the intersection of gender and politics for a prominent American magazine, notes that the personal nature of the newsletter lessens hierarchical divides between writer and reader:

I’m much more open in the Substack than you could be in a traditional magazine article.… When you do a…review for a mainstream newspaper there is more of a status divide.

Thus, newsletters give these writers the opportunity to build more dialogic relationships with their readers and express more personalized viewpoints.

While interviewees recognize that newsletters offer a more personal outlet, they remain careful to uphold professional norms of journalistic production. They do so by differentiating their newsletters from their formal career writing, and by integrating the role of their personal experience and voice within journalistic standards.

A journalist who runs the culture and economics section of a digital outlet uses her newsletter to write articles related to, but separate from, her formal career: “The newsletter is connected to the interests of [my section], but not really something we would ever do.” She describes her newsletter as “janky” because it does not contain “original reporting…it’s mostly Googling.” The purpose of the newsletter is to write “something that’s my own, that has nothing to do with the job.” In this way, she separates the personal and playful nature of her newsletter from the standards and rigor associated with the journalistic norms important for her professional work.

Other writers uphold journalistic standards by incorporating the personal nature of the newsletter with journalistic norms. A national political reporter describes how he thinks “the objectivity of a journalist involves not coming into a story as a blank slate, but in the method that they report the story, and the fairness with which they report the story.” He says his personal identity influences how he relates to politics without compromising journalistic standards:

I grew up as a midwesterner, and so I have opinions about the unique identities of states like Michigan versus Ohio, or Indiana versus Illinois. I have preconceptions about the states, but as I’m reporting on them, I do think it’s possible to be cognizant of those preconceptions and use the method of reporting journalism to be open-minded and fair and balanced in the actual reporting about those states.

For him, the journalistic method of reporting neutralizes preconceived and personal perceptions to create “fair” and “balanced” information.

Overall, however, these interviewees express concern about how newsletter production may affect journalistic standards without the enforcement of norms and gatekeeping provided by media institutions. Two interviewees explain their worries that newsletters cannot provide the same quality of information.

The first, who writes for a prominent American magazine, claims:

[Newsletters are] great for comment. If you want to have strong opinions on established facts, then that’s something that newsletters can do very well. But who is the person doing the hardest bit of journalism, which is establishing the facts in the first place? There are no shortcuts for that, which takes a really long time and costs a lot of money.

The second journalist, who focuses on audience engagement for a national publication, agrees:

I think about all the rigorous editing and the rigorous reporting that goes into more traditional outlets that is not done on the personal level, which I don’t think is bad all the time. But I do think that when we see personal reporters with their own newsletters pursuing ambitious stories, I think a lot of times there may be issues of accuracy.

For these interviewees, journalistic norms of reporting, objectivity, and accuracy remain valuable and important standards. Newsletters prove useful as a tool for commentary, essaying, or, as one veteran reporter describes, “writing off the news”—using traditional news stories as a jumping-off point—but newsletters cannot stand in for the types of reporting core to journalistic norms and identity. Indeed, these journalists strongly identify with their professional roles. As one journalist describes: “It’s through me like a stick of rock. I don’t know what I would be if I didn’t do this job.… I would have to radically rethink my life and start all over again.” In this way, journalists use their newsletter in connection to dense networks and ties to the media industry that continue to structure journalistic careers, norms, and identity.

Newsletters as a Journalistic Alternative

Interviewees who use Substack as their main career activity consider the platform to be an innovative, entrepreneurial venture to structure alternative career paths. They critique the structures and norms of institutional media, noting the ways in which Substack provides a new media model. Notably, they point to connections with corporations and reliance on advertising that corrupt the quality of information in the media. A beauty writer critiques the connection between beauty publications and the commercial beauty industry: “Publications typically work hand in hand with brands to create content, such as product reviews and stories with favorable PR angles.” Similarly, a political reporter critiques advertising media models for incentivizing clickbait and feeding polarization:

In the news world, most journalists, media outlets, television networks, and podcasts survive on advertisement revenue. Ad revenue is driven by viewership. That means the more people see an advertisement, the more valuable it is. This incentivizes reporters, editors, radio hosts, television stations, and news outlets to make their content as viral, explosive, and sensational as possible.… It also creates conflicts of interest between publishers and the people paying them to run their advertisements.

The writer describes how he feels his newsletter offers a transformed product:

[My newsletter] is entirely subscriber supported. By asking my readers to support this newsletter instead of advertisers or investors, I am incentivized to create good content…not content that is clickbait or designed to go viral or make an advertiser happy.

By capitalizing on the subscriber model, he seeks to change the relationship between reader, writer, and journalistic content. Paid subscriptions directly connect him to his readers, making him accountable to and empowering his audience, rather than attracting investors or advertisers. In this way newsletters offer an alternative structure to produce news and information.

Journalists in the study also critiqued the hassle, inefficiency, and precarity of journalistic careers, incentivizing them to focus more on their newsletters as outlets in which they feel they have more control and freedom over their work. A veteran reporter describes how she experienced a decline in opportunities to write for major publications:

The media is shrinking…the traditional media that I’ve written for, like the Washington Post, the Wall Street Journal, all of these, they can’t afford freelancers. They don’t have space; they don’t have staff.

A Pulitzer Prize–winning journalist similarly describes frustrating experiences working within institutional media:

It’s an annoying way to work, and it doesn’t pay great.… I would race to get a piece done, and then the publication would be like, “Oh, we’re actually not going to run it for the next 24 hours because this other thing happened.”… You end up playing email tag with an editor: it’s like, “Hey, did you get the piece that I sent you?” And then the news peg passes, and then you have to look for a new news peg, and then you have to rewrite the piece because time has gone by…then, like, having to rewrite it four hundred times because the news peg passed in the time that it took them to write you an email.

Starting a newsletter appealed to him because he can do “it on my own schedule.” He can directly distribute content to his readers when he feels his pieces are ready, rather than wait on the whims of a publication’s news cycle. Thus, newsletters offer an alternative that gives journalists freedom, independence, and control over their workflow.

Given the formalized nature of Substack as a career path, these journalists describe the importance of subscribers for their livelihood and as an economic model for their careers. An award-winning investigative journalist describes how his subscriber base serves as a career resource:

I can create a subscription base that will be portable, and maybe in some ways more durable, or no less durable, than actually getting a job at a big institution.

Another long-form journalist describes how he was inspired by the success of subscription podcasts to build his own newsletter:

For example, the Chapo Trap House guys who were making so much money on Patreon.… I was like, “Wow. It never occurred to me to do that.”… It was like, “So you can put something out in the world and people will pay you four, five, six bucks a month just because they like it. And you can make a lot of money that way.” I looked at that type of business model, and that’s what the Substack does.

In this way, digital platforms serve as a tool to actualize transactions between writers and readers. Subscriber models incentivize content quality by the necessity of attracting readers. Thus, from this perspective, subscriptions ensure newsletter integrity despite often lacking the traditional fact checkers or editors found in traditional media.

Last, these interviewees critique power structures in institutional news that they feel limit the range of legitimate perspectives included in news content. A music writer describes his experience at a culture magazine that led him to quit and focus on his newsletter, where he can highlight different voices, perspectives, and stories. “People around me [at the magazine] were more interested in perpetuating misogyny and bigotry and marginalization of anybody that’s not a man, essentially, or identifies as a man,” he says.

Similarly, a food writer describes her dissatisfaction with institutional food media given the exclusion of multiple perspectives and political ideas:

When I was writing for food magazines it was very much centered on a middlebrow white American gaze. You’re writing for Middle America, and don’t upset them. That was the perspective.… There is just a lack of interest in systemic problems outside of talking about racial representation or gender representation. There’s an idea of diversity as just different skin colors and genders, and not political ideas. So that’s what I’m able to actually present in my newsletter.

She now focuses almost exclusively on her newsletter, where she writes about the intersection of food, ethical consumption, economics, and sustainability, hoping to inform readers that “food decisions aren’t made in a vacuum.” She values the fact that the Substack platform allows her to “own my own time” and “create the thread of my own thought” to produce alternative content and arguments she felt institutional publications did not accept.

Newsletters can offer an alternative space to produce content outside journalistic norms. Instead of adhering to norms of objectivity, journalists in this survey describe their methods of content production as intentionally incorporating subjectivity as a different basis to produce information.

A journalist with a background in reporting on tech, markets, and fashion describes how when he worked for institutional publications, he felt tokenized as a reporter of color and forced to write about certain topics and narratives. In his newsletter, he embraces his full identity to center his point of view:

If you come from an underrepresented or overlooked or underserved community, it’s difficult to not bring all of you into a story and [keep] different parts of yourself siloed off to tell a story. That’s a bit dehumanizing. I think part of making roles and creating space for as many storytellers and journalists and reporters as possible is to really get rid of this idea that you can’t be fair or accurate if you have a point of view. I think that the idea of objectivity and leaving your identity at the door, all that does is serve patriarchal white supremacy. It serves the people who have always gotten to tell the stories.… I just try to tell stories that matter to me…I write from my point of view.

He challenges journalistic norms of objectivity by drawing on his own perspective as a legitimate alternative to inform his work.

In this way, newsletters shift journalistic identity to incorporate individual experience and traits traditionally conceptualized as separate from professional roles. Rather than describe their professional titles or learned skills as core to their identity, these journalists reference innate qualities such as “curiosity,” “empathy,” “deep thinking,” and “skepticism” as defining professional traits and identities. As one says: “Journalism for me is not a profession—it’s a personality disorder. I’m nosy. I’ve got a big mouth. I’m aggressive and pushy.” She identifies as a journalist as a personality trait and intrinsic part of her identity, rather than attaching the identity to a professional position, skill, or role. Journalistic status composes both a personal and professional identity. Journalists in the study continue to see themselves as professionals across contexts or roles, rather than within specific career positions or performing certain job skills.

Newsletter as a Journalistic Lifeboat

A third group of interviewees describes using Substack as a temporary tool when they lack other career opportunities or resources. These journalists tended to gravitate to the platform after losing employment at other media outlets. As such, Substack offers a way for them to structure their time, pursue their writing, maintain their journalistic identities, and continue in their professional field. The platform provides a free, accessible, but temporary outlet for journalists who hope to transition to other platforms or opportunities.

These interviewees tended to be the most skeptical about Substack as a media model and platform. They do not see newsletter writing as a sustainable career activity or resource. Fundamentally, these journalists critique the financial model of newsletter writing and the difficulty of amassing subscribers without a pre-established reputation, digital following, or institutional ties to legacy media.

A freelancer who decided to end his Substack newsletter describes the financial feasibility of the pursuit at length:

If you start a newsletter without a preexisting fan base, or at the very least a large and active Twitter following, building an audience…is very tricky. You basically need to churn out posts and hope a couple of them go viral on Twitter so you get a ton of more subscribers.… But the economics of this are pretty unfriendly. If you got 500 subscribers to pay you $5 a month, you’d be making $2,500 a month, or, oops, actually $2,250 after Substack takes its cut. And you’re writing at a minimum a post a week, probably more than that. If you’re doing two posts a week, say eight a month, you’re actually only making $281.25 an article. That isn’t that bad, but then you consider that the burger place down the street pays $19 an hour. You really aren’t in “livable wage” territory from a Substack alone until you have thousands of paid subscribers. And if you’re using Substack to supplement income from freelancing or a day job, it’s a lot of work.… Once you put up a paywall, you have the additional problem of a lot of your content now being hidden from public view, i.e., it can’t go viral and attract new subscribers.

He laments that subscription media models are unfeasible for most writers, as well as illogical, given the tension between paywalling content and attracting new subscribers. Furthermore, rather than newsletters serving as an outlet for alternative narratives or in-depth thoughts, he describes them as aimed toward “virality” and produced on a fast-paced timeline. Overall, by comparing Substack writing with service work, he highlights the low status and financial difficulties of the pursuit.

These writers, like many others, describe growing their subscriber base as the most challenging part of producing a newsletter. Across the three categories of journalistic work, no writers felt they had figured out the best newsletter media model. All felt uncertainty in the best way to balance growth, financial viability, and content accessibility. The difficulty in monetizing their newsletters proved particularly detrimental to writers without other income streams. Thus, journalists relying on Substack as a lifeboat expressed the most frustration because they remain in precarious professional positions.

A veteran reporter at a major urban paper lost his job when the publication went through layoffs. He started a Substack newsletter as “sort of my best option as far as employment.” However, after a few months he was disillusioned with the platform:

It’s not sustainable. It’s been very difficult, frankly, to increase subscriptions. I pretty much hit a wall about two months ago and haven’t been able to increase it. So I’m pretty down on the Substack model. I think there’s just too many things out there, too many subscriptions, and it’s too hard.

Newsletter writing becomes economically unsustainable without a substantial reader base. Indeed, interviewees described the most successful writers on the platform as those who “already had these huge Twitter followings” or “already have a brand, already have a name, and already have a reach.” In this way, these journalists see newsletter writing as supporting existing structures of power and privilege within the media, rather than providing an alternative environment.

Furthermore, these journalists argue that subscription newsletters do not incentivize quality information. Rather than newsletters serving as outlets for journalists to write about their passions, deepen their writing skills, or produce content from an alternative perspective, they feel as if newsletters do not allow for the types of meaningful content they strive to produce.

A political reporter describes how creating newsletter content became less of a priority

“Write a new newsletter” gradually slipped to the bottom of my to-do pile. I did less reporting for the newsletter and treated it more like a place to put my thoughts about the stuff I was working on and reading.… I don’t really want to write these kinds of stories anymore.… “The conversation” often seems to consist of a gaggle of pundits and Twitter addicts nodding in agreement with one another.

Furthermore, other journalists in the survey describe Substack subscription models as seeming to prioritize sensationalist and potentially viral content to attract readers and generate attention. A culture writer who now works as part of a bundled newsletter cooperative describes such incentives:

The discursive oxygen around the site has been allocated or has been sucked up by people who are using it in a way to stoke rage, or stoke anger, outrage, that sort of thing. When you create those feelings, they become powerful feelings that make people want to subscribe.

In contrast, she aims to “contextualize,” “analyze,” and “do some reporting and actually talking to people” in her work. To her, anger and outrage do not equate to meaningful content production, even if they garner more attention or subscribers.

Some interviewees also critique Substack as a platform and business that participates in the media environment given the uneasy relationship between media and technology companies. One writer describes his worries about the power that technology companies play in structuring what digital content gains visibility:

A lot of stuff with Big Tech and Facebook and Google is kind of scary these days, with a lot of alternative media locked out or at least buried in Google searches. I’m worried about Silicon Valley’s influence in the media.

Such critiques led interviewees to desire that Substack take more responsibility for the content produced and promoted on the platform. To them, it functioned like a publisher that curates and distributes content, rather than as a neutral digital tool.

Another collection of young journalists who experimented on the platform but since moved their writing to an independent site critiqued Substack’s policies:

Substack could have been a great place for experimentation that breaks away from the bigoted speech that’s dominated American newspapers during pivotal moments of social transformation (see how newspapers framed integration, interracial marriage, and gay marriage). Instead, it’s more of the same. Substack isn’t the future of media. It’s just a content management system run by a company that aims to prioritize profit over people’s lives.

From this perspective, rather than representing a hopeful or useful media model, Substack represents the perpetuation of the faults of traditional and institutional media. Thus, this subset of journalists views newsletter writing as an unsustainable pursuit and problematic media model.

A veteran international reporter sums up this view with his critique of the current media ecosystem, in which smaller publications and opportunities struggle to exist, as well as Substack’s role within it:

If you consolidate a business into big players and then that sucks up all the talent, then everything else becomes nothing more than an audition. So your book is an audition, and your big article somewhere is an audition, and your leadership of a midsized manager’s room is an audition, and your Substack is certainly an audition. The only place you’re going to get quality editing, good access, some imprimatur that matters under a living wage, is going to be, like, three places. That doesn’t feel sustainable to me. I’m suspicious of the Substack model, because it seems to be based on the idea of a lifeboat more than on the idea of an actual legitimate setting.

These journalists feel frustrated by a lack of opportunities in institutional media and hopeless about the promise of independent digital tools. Such pessimism leads them to express distance from their journalistic identity. As the international reporter continues: “My current job is to pay my mortgage and feed my kid in an industry that has done its best to die over the past decade.”

Conclusion

This report presents a case study of the digital newsletter platform Substack to explore how journalists use and incorporate it into their careers and how it relates to the broader media environment. Rather than falling prey to technological determinism, willful optimism, or dispiriting pessimism about the role of technology in the future of news, the report highlights some of the ways in which digital technologies can be used and understood.

In particular, I identify differences between journalists who use Substack to (i) complement their work for other publications and outlets, (ii) create an alternative media environment, and (iii) keep them connected to their professional field when they lack other opportunities and resources.

Each journalist’s use of Substack is associated with specific career goals, strategies of content production, and conceptions of journalistic identity. By focusing on the practices, intentions, and understandings of digital newsletters expressed by the journalists themselves, the report highlights how structures of news work may influence journalistic careers, as well as how journalists shape the role, use, and understanding of digital tools.

My findings point to an increase in the range of methods and logics journalists rely on to produce information as they access expanded resources to build their careers. As communication technologies continue to evolve, journalists confront ever more opportunities and tools to shape their work and careers. We see journalists experimenting not only with newsletters but with media such as podcasting and texting, and structures such as publishing work as a collective and hosting live events. Such opportunities expand the types of work journalists produce, incorporating new skills, forms of expertise, audience relationships, and methods of reporting. At the same time, these experimentations present themselves as public, facing toward an audience as journalists seek to publicize and monetize their work and brands. As journalistic careers evolve to include a wider variety of styles, tools, and methods, the opportunities also grow for audiences to access diverse content.

While these trends expand the modes of and voices able to contribute to public conversations, they also contribute to phenomena such as the crises of expertise, ontological insecurity, and post-truth politics without common norms that structure the flow, distribution, and norms of producing and accessing news and information. Readers increasingly access a high-choice media environment via newspapers, websites, tweets, podcasts, and newsletters, among others. Such a buffet of content can overwhelm and segment media consumers, limiting the amount of shared content and perspectives available to audiences.19 Benkler, Yochai, Rob Faris, and Hal Roberts. Network Propaganda: Manipulation, Disinformation, and Radicalization in American Politics. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2018. Boczkowski, Pablo J. “Abundance.” Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2021. Nielsen, Rasmus Kleis, and Richard Fletcher. “Democratic Creative Destruction? The Effect of a Changing Media Landscape on Democracy.” In Social Media and Democracy, edited by Nathaniel Persily and Joshua A. Tucker, 1st ed., 139–62. Cambridge University Press, 2020. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/9781108890960.008. Prior, Markus. Post-Broadcast Democracy: How Media Choice Increases Inequality in Political Involvement and Polarizes Elections. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007. While structures such as newsletters can allow journalists to capitalize on niche audiences and produce content through a greater variety of means and media, these trends also present challenges for creating shared understandings of facts and narratives—one of the traditional functions of journalism as a pillar of civil society. It raises the question of the relationship between an increase in media content and the health and robustness of the media environment. Thus, newsletters and digital platforms offer new media opportunities, as well as challenge some of the core functions of news work.

Furthermore, we see the interrelationships and dependencies between digital technologies and traditional media institutions. While digital tools are often touted as offering independence, the ways in which alternative technologies affect structures of power and privilege within the media remain limited.

Interviewees employed by traditional media institutions often sought to uphold objective norms and climb traditional career hierarchies. In contrast, interviewees more focused on digital platforms embraced the freedom to create content on their own timelines, based on their own inclinations, and incorporating their own perspectives. In this way, they articulated alternative goals of expressing themselves, garnering attention online, building community, and connecting directly with their audiences.

These styles and goals contrast with the more authoritative voice of professionalism backed up by journalistic norms and traditionally displayed in dominant media publications. However, journalists working on digital platforms must confront limits to their independence, counternormative trends, and creation of alternative media spaces. Even when working independently on digital platforms, journalists rely on dominant professional outlets and publications to publicize their work, gain visibility, and source content.

The computational portion of this report showed that newsletter writers most often link their work to existing dominant outlets. This creates webs of media production that include both institutional and independent forms of news work centered on select core publications, themes, and figures. Furthermore, within that web, digital platforms themselves become central players as their tools, algorithms, and support shape the types of content produced and made visible. Thus, the report highlights how an expanded media environment that includes an array of journalistic opportunities presents both new potentials and pitfalls for empowering journalists and supporting their careers.

In conclusion, I highlight several potential avenues for future research.

Journalistic careers: How are journalists using other digital tools? How do these opportunities exacerbate or mitigate employment precarity? How sustainable is journalistic work on digital platforms, and newsletter writing in particular? What types of opportunities and careers do journalists hope for that can be supported by new technological tools?

Political economy of news work: How do subscriber-based funding models of news work change the incentives for journalistic production? What role do technology companies play in supporting the production and distribution of journalism? How should these platforms and companies be regulated and/or held accountable for worker livelihoods and the content produced using their tools?

Audiences: What attracts readers to journalistic outlets, media, and writers? How do readers interpret journalistic writing distributed through various means? How do they relate to the readers of similar and/or different outlets and content? How do readers evaluate information from different sources and distributed on different platforms? How do these sources interact in ways that are complementary and/or contradictory in shaping audience views?

Challenges to professional norms: How are journalistic norms of objectivity, balance, and fairness being challenged by new opportunities for journalistic production? What alternative norms are journalists using as an epistemological basis for their work? How do these norms differ across platforms, publications, and individuals? How are institutional newsrooms reacting to and incorporating new norms of information production?

The media industry will continue to evolve, and journalists will continue to experiment with new tools, ideas, and career paths. While each development brings challenges, unanticipated impacts, and controversies, the journalists in our study remain committed to their work. Some even find hope within the complexity and failure of these supposed media solutions. As one reporter remarks: “It’s good a lot of people are experimenting…the industry is now being fully shaken up.”

Appendix A: Interview Demographics

Table 1: Respondent Demographic Characteristics. *Includes Latinx, East Asian, South Asian, Black, Middle Eastern, North African, and mixed-race respondents

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.