Small-market newspapers constitute the majority of newspapers in the United States. What is it like to work at these publications? And what do journalists themselves identify as the fundamental challenges and opportunities for this sector?

We set out to answer these questions by asking local journalists at daily and weekly newspapers with circulations under 50,000 to tell us directly about their working lives. Of the 7,071 newspapers regularly published in the United States (daily and weekly), 6,851 have circulations smaller than this number.1

However, their experience is typically underrepresented in wider industry conversations.2 Our research seeks to redress that by providing a platform for discussion about the smaller market experience.

Through an online survey completed by 420 respondents across the United States we discovered a cohort, which describes itself as hardworking, optimistic about the future of its industry, and eager to know more about emerging digital tools for journalistic storytelling.

Despite cuts and job losses over the past decade, as a group our respondents were more upbeat about their future than perhaps might be expected. At the same time, local journalists remain aware of the significant challenges their sector faces. Respondents told us about issues in recruiting and retaining young journalists, the difficulty of establishing relationships with the next generation of local news consumers, and the wider challenge of overcoming general cynicism toward both the journalistic profession and the mainstream media.

These findings both confirmed and challenged our expectations. It’s our hope that this survey—and the wider paper we are producing in parallel to this report—can help ignite fresh discussion about the importance of local newspapers. In the process, we hope to provide pointers for further research, and to help stimulate debate about the future of this key component in our media and information ecosystem.

Executive Summary

The observations in this paper are based on the results of an online survey conducted between Monday, November 14 and Sunday, December 4, 2016.

In total, we received 420 eligible responses (a further 10 were excluded as participants were outside of the United States). Contributions primarily came from editors and reporters at small-market newspapers.

Survey respondents identified a number of key challenges for the sector, including:

- Shrinking newsrooms: More than half (59 percent) of our survey participants told us that the number of staff in their newsroom had shrunk since 2014.

- Recruitment: Low pay, long hours, and limited opportunities for career progression can impede the attraction and retention of young journalists.

- A long-hours culture: Many respondents reported that they regularly work more than 50 hours a week.

- Job security: Just over half of respondents (51 percent) said they feel secure in their positions. A further 29 percent had a neutral view (neither positive nor negative) about their job security.

Despite these considerations, we encountered a sense of optimism among much of our sample. This confidence is rooted in an understanding that small-market newspapers are often close to their communities—with journalists sharing similar goals and lives to their audience—and a recognition that much of their reporting is not replicated elsewhere.

Nevertheless, respondents were also aware of emerging issues, such as establishing relevancy with the next generation of news consumers. As one participant told us: “We need to find how to connect with elementary, middle, and high school students, and usher them into an understanding of what journalism is, and why it is a pillar of a thriving democratic society and culture of free thought and progress.”

Social media and emerging storytelling formats such as live video may help do this, and we found strong levels of interest in some of these spaces.

Video reporting is already mainstream at local newspapers (85 percent of respondents told us their paper did this), as is organizational usage of Facebook and Twitter. Less popular is podcasting (used by 25 percent of respondents’ newspapers) and emerging tools like chat apps, or augmented and virtual reality.

It’s our view that usage of these newer platforms may grow as their storytelling potential becomes better understood and their presence becomes more established. However, it’s also necessary to place journalists’ lack of interest in these tools within the context of the limited resources (time, money, personnel) available at many local newspapers. These realities may very well restrict the wider digital ambitions of some smaller outlets.

Interestingly, although many local newsrooms have shrunk over the past two to three years, more than half of our respondents reported that their working hours haven’t increased. This finding is perhaps all the more surprising given the increased demands on journalists’ time. Our sample revealed that many local journalists are required to produce more stories and spend more time on digital output than they were just two years ago. But although local journalists often work long hours, they’re not necessarily working longer hours than they were before.

Looking to the future, our research revealed that local journalists are interested in learning more about video reporting, live video, and podcasting (even though usage of the latter is low). They typically learn about these subjects through industry media (Nieman Journalism Lab, Poynter, MediaShift, etc.), rather than by attending formal training or industry events. And when it comes to using new technologies, most respondents reported that they are self-taught. This may be an area of opportunity that membership organizations, J-Schools, and tech companies are well placed to help address.

The findings from our online survey—and the 60 qualitative interviews we conducted separately with industry leaders—suggest a plurality of experience across the local newspaper industry. Subsequently, we believe a more nuanced conversation about this sector in required. The newspaper industry, even within this smaller stratum of newspapers, is far from homogeneous.

Our conversations with local journalists found a cohort eager to know more about the experiences of their peers. As a result, we welcome moves to increase coverage of the local media sector by leading trade publications. Richer coverage and research of this industry will help to inform and inspire local journalists, policymakers, and funders alike. We look forward to seeing what happens next, and to being part of that conversation.

Background

The last 10 years have not been kind to journalists and the newspaper profession. According to the Pew Research Center, the past two decades saw the elimination of 20,000 positions at newspapers across the United States, with a 10 percent decline in 2014 alone.

In 2015, notable cuts were seen at major newspapers and newspaper groups such as The Philadelphia Inquirer and Daily News, Tronc (formerly Tribune), The New York Daily News, The San Diego Union-Tribune, The Orange County Register, The Seattle Times, The Denver Post, and The Boston Globe,3 among others.

This trend continued into 2016. Adding insult to injury, the website CareerCast listed “newspaper reporter” as the worst of 200 jobs in 2016. This conclusion was based on the closure of publications, leading to the availability of fewer new jobs, and a decline in ad revenues, leading to “unfavorable pay” for current employees.4

Alongside this, in September 2016 the polling company Gallup reported that Americans’ trust and confidence in the mass media “to report the news fully, accurately and fairly has dropped to its lowest level in Gallup polling history.”5

Another 2016 Pew study about the modern news consumer revealed: “Few [audiences] have a lot of confidence in the information they get from professional outlets . . . Only about two-in-ten Americans (22%) trust the information they get from local news organizations a lot, whether online or offline, and 18% say the same of national organizations.” 6

Added to this, the nature of the 2016 presidential election and the accompanying rhetoric of fake news have lead to further distrust in the news media. In December 2016, Pew reported that 64 percent of Americans “say completely made-up news has caused a great deal of confusion about the basic facts of current events,” and almost a quarter of Americans reported to Pew that “they had shared fake political news online.” 7

These recent studies make for sobering reading. They reveal that, among large parts of the population, the media is witnessing declining levels of trust, while the economic forecast for the newspaper industry continues to look challenging.

Juxtaposed with this well-known and researched backdrop, we felt that the views and experiences of many newspaper journalists often went untold, especially in the local arena. Our research, supported by the Tow Center for Digital Journalism at Columbia University, seeks to remedy this by focusing on small-market newspapers and the journalists who work for them.

A deeper understanding of this sector is important, because it contains the daily and weekly news sources to which many Americans continue to turn for information.8,9,10

Local newspapers make up the bulk of the American newspaper ecosystem, yet they typically receive less attention from industry watchers than larger, better known outlets like The Washington Post and The New York Times.

There are approximately 7,071 regularly published newspapers in the United States (daily and weekly), and of these, 6,851 have circulations of fewer than 50,000.11 The majority of these papers—titles like The Wickenburg Sun (Wickenburg, Arizona) and the McKenzie County Farmer (Watford City, North Dakota)—often go unnoticed. Yet, their continued importance to the communities they serve and their contributions to our wider media ecology mean they merit exploration.

While we are getting closer to knowing how many newspapers exist in the United States, largely thanks to the database collected by Penelope Abernathy and her research team at the University of North Carolina, the experiences and opinions of journalists working in this sector tends to remain somewhat under-reported.12 In an attempt to help redress this, we asked local journalists—via an online survey—to tell us about their experiences. Based on these findings, we found a hardworking group that was optimistic about the future of the sector and interested in better understanding how digital tools and platforms can support their work.

At the same time, they also recognized that their sector is not without its challenges. Local journalists are not immune to the cynicism and criticism of journalists and the wider media that dominate our current news cycle. They were also grappling with the challenges of attracting and retaining both journalistic talent and younger, paying news audiences.

The findings from this survey complement our larger landscape study, “Local News in a Digital World.” That report tells the story of small-market newspapers through in-depth qualitative interviews with experts and practitioners. In contrast, this study focuses on the work habits and attitudes of editors and reporters at these smaller outlets.

Taken together, our two reports—“Local News in a Digital World” and “Life at Small-Market Newspapers”—offer us a detailed understanding of the state of small-market newspapers in the United States. They examine everything from business practices and strategic challenges, through to usage of digital tools and the wider journalistic experience.

We are grateful to everyone who took the time to participate in this study, and generously shared their insights and experiences with us.

Methodology

During the summer of 2016 we began work on this project by analyzing relevant, recent surveys from organizations such as the Pew Research Center, the Engaging News project at the Texas Annette Strauss Institute for Civic Life at the University of Texas at Austin, the annual ASNE Newsroom Employment Diversity Survey, among others. The purpose of this desk research was to avoid duplication with our own proposed study.

This analysis took place alongside 60 in-depth, qualitative interviews with industry experts and leaders, the conclusions of which informed our sister study, “Local News in a Digital World.”

Following completion of these two activities (desk research and qualitative interviews), we developed an online questionnaire aimed specifically at journalists working for small-market newspapers. The Tow team reviewed and approved of the questionnaire, while Dr. Talia Stroud at the University of Texas at Austin and Josh Stearns at the Democracy Fund offered additional insights.

To help promote the study when our questionnaire went live, we wrote a short article for Tow’s Medium page and undertook a range of other activities, including emailing every State Press Association and contacting other relevant stakeholders such as the National Newspaper Association, the National Newspaper Publisher Association, the Society of Professional Journalists, and the Online News Association.

Our survey was highlighted by the weekly Local Fix newsletter (December 2, 2016)—which is part of the Democracy Fund’s Public Square Program—Nieman Journalism Lab’s “What We’re Reading” list (November 21, 2016), the Tow Center’s email newsletter, and in a banner advertisement on the Editor & Publisher website. We also shared a link to the live study on our own personal social media channels.13

Our online survey was in the field for three weeks from midnight (ET) on Monday, November 14, 2016 to 11:59 p.m. (ET) on Sunday, December 4.

We received more than 420 responses from around the country, primarily from editors and reporters. Responses were guaranteed anonymity. By allowing respondents to leave non-attributable answers, we hoped to facilitate a conversation whereby participants could freely critique their own operations without the risk of attribution.

In order to participate, respondents had to be employed at an American newspaper with a daily circulation of under 50,000 (which is how we define “small-market newspaper”). Weekly titles were also included in this mix. Employment status was self-declared.

Larger titles, those without a print product, or publications based outside of the United States were removed during our data analysis. Of 430 responses, 10 fell outside of these parameters, leaving a total of 420 responses for review.

Respondents were able to skip certain questions, while still allowed to complete the remainder of the survey. We made this decision to ensure the highest possible completion rate (also allowing participants to potentially bypass questions that were not relevant, or possibly unclear, to them). Completion rates varied by question, and these numbers are clearly identified in each chart used in this report.

Map of online survey respondents

Because respondents were self-selecting, our findings do not constitute a representative sample. Our conclusions should therefore only be seen as indicative of the state of the wider small-market newspaper industry. Nonetheless, as shown in our map of survey respondents above, respondents reflect a broad geographic experience. They also come from a mix of daily and weekly publications, an important feature given that weekly newspapers—which comprise the bulk of American newspapers—seldom receive the attention we believe their circulation figures suggests they deserve.

In the following pages, we detail the key findings from our online survey. Where necessary, we have added explanations as to why certain questions were asked.

We start with an overview of our respondents, and then move on to a seemingly simple but crucial question: “What is it like working at a small-market newspaper?” We then delve deeper into specific areas such as technology usage and the concept of engagement, before concluding with the “big picture” and the future of the industry.

These insights flow from the 420 journalists who kindly took the time to share their views and experiences with us. Where we have added our own insights and analysis based on our further work in this space, we have sought to clearly identify this as such.

Overview of Survey Respondents

Key points:

- 57 percent of respondents have been working in local papers for 10-plus years

- 36 percent of respondents have been working in local papers for over 20-plus years

- 39 percent of respondents were over 50 years old

- 54 percent of respondents defined themselves as editors or reporters

Just over half of our respondents were editors or reporters

We began our online survey by asking a few questions designed to ascertain the job title, age, and years of experience of our respondents.

The self-declared job titles of those who completed our online survey were primarily either editor (section/managing) or reporter. Together, these two categories represented roughly 54 percent of all respondents.

The remainder of participants included those who ticked “other” (24 percent) or “digital/social media” (5 percent) from the job options provided.

57 percent of participants have worked in local papers for 10-plus years

The largest single group of our respondents (36 percent) told us that they had been working in local newspapers for more than 20 years. The second-highest category (21 percent) had been working in the sector for between 10 and 19 years.

39 percent of respondents were over 50 years old

Alongside this, we also asked respondents how old they were. Their ages were relatively evenly distributed, but did skew older: 18–30 (27 percent), 31–49 (33 percent), 50-plus (39 percent).

What Is It Like Working at a Small-Market Newspaper?

Key points:

- 70 percent of respondents told us they spent more time on digital-related output than they did two years ago

- Nearly half (46 percent) of respondents said the number of stories they produce has increased in the past two years

- Over half (55 percent) of respondents said their working hours have not changed in the previous two years; another 34 percent reported that their hours had increased

- While a 50-hour week is standard, many people work many more hours than this

- 59 percent of respondents reported that their newsroom had shrunk since 2014

- Attraction and retention of new talent is a problem for the industry

Journalists are spending more time creating content for digital channels

Given the transition to digital,14 we were hoping to get a sense of how journalists at small-market newspapers apportion their time across digital and print properties. Most of our respondents told us that they split their hours between print and digital.

Overwhelmingly, respondents said that the focus of their output now includes producing more content for their digital operations. Nearly three-quarters of our online sample (70 percent) stated that they spend more time on the digital side of their role, when compared to two years ago.

Nearly half of respondents said their story load had increased since 2014

As well as seeking to understand changes in the focus of respondents’ work, we also wanted to understand if the volume of output had changed during the past two years. From our sample, 46 percent of respondents indicated that the number of stories they produce has increased during this time, while 37 percent reported that their story load had remained the same.

In the space provided for written comments, many respondents noted the continued importance of the print product to their newspaper’s survival. As one respondent told us: “We need to respect print and grow digital.”

Subsequently, there still remains a strong emphasis on producing content for print. More than a third (36 percent) of participants working on the print product for their paper reported that they are producing more print stories than two years ago. Still, local journalists do recognize the need to grow and focus on digital. But this is not, it seems, an “either/or” scenario. In an increasingly fragmented news landscape, they focus their attention on both avenues. Not just one.

A long-hours culture is standard

Despite these self-described changes, meaning the shift to spending more time on output for digital channels and the increased number of stories individuals are expected to produce, working hours have remained relatively consistent for many journalists.

Across our sample, 55 percent of respondents told us that their hours have stayed the same over the past two years, while 34 percent said their hours had increased. When looking at a typical working week, the average time worked clocked in at 47 hours, while the mean was slightly higher at 50 hours a week.

Authors’ commentary: Long hours are nothing new

Newspaper staff continue to work above and beyond the standard 40-hour work week. According to an article from Poynter in 2013, the constant demand on journalists’ time is one of the reasons why CareerCast listed “newspaper reporter” as the least desirable job.15 As Tony Lee, CareerCast’s publisher, told Poynter, “You’re essentially in demand all the time. Clearly there are times when you’re off, but if something happens on your beat or you’re in a small town, you need to drop what you’re doing and go to work.”

Pay, stress, and hours were also cited as “reasons newspaper reporter was always a bad job.” The article noted that “fewer openings,” “more demands,” and “uncertainty” are all “reasons newspaper reporter is a worse job than it used to be.”

These findings are not unique to the United States. A 2006 study from the United Kingdom reported that many local and regional journalists work more than 40 hours a week. A survey of 399 journalists found that a third reported working between 41 and 45 hours a week, while 19 percent said they worked close to 50 hours a week. Among this group, “64 journalists said they work 51 hours or more.” 16,17,18

In our own study, when asked how many hours respondents worked in an average week, one wrote “up to 116” hours a week, while others gave answers like “all of them” or “as many as it takes.”

Staffing levels in many local newsrooms continue to fall

Alongside understanding shifts in personal output and working hours, we also wanted to understand how this experience mapped against wider changes in the newsroom. To help us determine this, we asked about changes in the size of a respondent’s newsroom over the past two years.

Confirming trend lines previously published by both Pew19 and CJR,20 59 percent of our survey participants told us that the number of people working at their publication had decreased when compared to two years ago. In contrast, just under a third (30 percent) said staffing levels had “stayed the same.”

Lack of resources can impact the breadth, depth, and quality of coverage

Our respondents suggested that some of the challenges the sector faces, including smaller newsrooms and demands to produce more print/digital output, can impact acts of journalism conducted at a local level. Fewer reporters may mean shallower reporting, while many journalists feel compelled to put in extra hours to ensure they can cover their beat effectively.

As one respondent observed:

The biggest challenge facing small-market newspapers is manpower and time.

As a reporter, I have many feature ideas I’d love to tackle, but I am not given ample time to report and dig as much as I’d like to, as my daily duties take up most of my work day. If smaller newspapers had more reporters, more meaningful stories would be told.

When staff is limited, so are stories. When time is limited, so is content. Reporters at my newspaper each work hard every day to try to tell more meaningful stories, which is why many of us work overtime on a regular basis to get this done.

Attracting and retaining young journalists can be a challenge

A review of the literature on local newspapers suggests that, historically, local newspapers were a jumping-off point for young reporters, with an established progression route through to major metros and national newsrooms.21,22 Our respondents, however, mentioned that today this may not be the case.

When asked, for instance, what they thought was the biggest challenge for small-market newspapers (aside from money and time) a number of participants’ answers reflected the aging demographic of their newsrooms and the difficulty of blooding young journalists. Barriers such as career progression, the diversity of small towns, and low pay were all highlighted as potential issues that newspapers need to be aware of when hiring this next generation of local reporters.

One respondent outlined the biggest issues to us:

From an editorial standpoint, that journalists are young, relatively untrained, and asked to do so much across multiple platforms. With a push to digital, my journalists don’t have free time to let stories grow in their minds.

Recruiting and keeping talented reporters. A small market is not always a great sell to potential employees, especially when trying to recruit reporters of color, LGBTQ reporters, etc., who might not feel welcomed in a small, white, conservative community.

It is also difficult to retain reporters for more than a few years. When they move to larger markets, they take their knowledge with them. It is difficult to create and maintain institutional knowledge and community rapport with a continuous shift in reporters.

Another respondent summed this up by saying, “The biggest challenge for small-market papers is being able to pay reporters enough to want to make a career in such publications. Barely making a living wage can take it out of the most dedicated journalist.”

Authors’ commentary: we need to discuss how to recruit the next generation of local journalists

The consequences of low pay and long hours can be seen in rapid staff turnover at many small-market newspapers. Often, this turnover can be more acute with newer entrants to the industry. Rapidly changing personnel can be disruptive for communities and newsrooms, and hiring and training are time-consuming processes.

While the industry constantly discusses the challenge of getting young news consumers to read and pay for newspapers, an issue we do not hear as much about is getting young reporters to stay in small-market newsrooms.23 This is a discussion we need to have if the sector is to be continually replenished and refreshed by young journalistic talent; and if the local newspaper sector is to be a viable career option for this age group.

Local journalists feel more secure in the job than you might think

Despite this challenging landscape, 50 percent of our respondents nevertheless indicated that they felt “very secure” or “quite secure” in their jobs.

Authors’ commentary: why are so many local journalists optimistic about their jobs?

That a sizable number of local journalists feel secure in their roles may be a reflection that small-market newspapers are not necessarily downsizing in the same way as their metro cousins. As an article in Editor & Publisher from the summer of 2016 suggested: “Small, community newspapers across the country are not just surviving, but—in many cases—actually thriving. Many of them have managed to dodge the layoffs and downsizing that larger papers have had to face.”24

Our survey data doesn’t necessarily validate this conclusion, but it does reveal that local journalists are less pessimistic about their prospects than we might have envisaged. Reasons for this tempered optimism may include an element of survivor bias among our respondents, or that—following recent cuts in smaller newsrooms—the opportunities for further reducing personnel may be difficult. After all, how much “fat” is there left to trim?

Technology and Emerging Platforms

Key points:

- Facebook is the most popular social network—for work and personal reasons

- Nearly 85 percent of respondents noted that their newspaper produces video reports, and over two-thirds (67 percent) use live video services like Facebook Live and Periscope

- Journalists want to know more about video reporting, live video, and podcasts, while they’re less interested in emerging formats like augmented, virtual reality (AR/VR), and chat apps

- Just under a third of our sample enjoyed formal training opportunities such as attendance at conferences

- The majority of journalists learn about market developments and new tools through online articles and by training themselves

- 70 percent of newsrooms in our survey use some sort of metrics tools/software

We know that journalists increasingly use a variety of digital tools to support their profession.25 Although some small-market newspapers were initially slow to transition to digital,26 our survey showed a clear desire among many local journalists to learn about and embrace many of the latest technological opportunities.

Digital tools can create new ways of working (for example, the use of Slack as an email replacement), while the emergence of platforms such as Live Video can enable reporters to tell stories and communicate with their audiences in new and engaging ways.

Just because local newspapers have smaller newsrooms than their metro and national peers does not mean they are devoid of innovation and experimentation. Many local titles are exploring digital tools, and doing so with fewer personnel than their larger counterparts.

However, the deployment of new digital technologies can be time-consuming, and in resource-challenged environments journalists may not have the hours to add this to their already-busy journalistic plate.

Small-market newspapers are actively embracing video and live video

We asked respondents to tell us about some of the emerging communication forms they are using. This included use of popular digital tools and platforms such as video reporting (used by 84 percent of respondents), live video (67 percent), and podcasting (25 percent).

In our sample, small-market, local newspapers were less likely to use chat apps (5 percent), augmented reality (0 percent),27,28 and virtual reality (5 percent)29,30,31—although we know from our wider research that these tools are being used by different newspapers. The Herald and News in Klamath Falls, Oregon, for example, has produced augmented reality (often referred to as AR, for short) content on a regular basis since 2015.32 AR stories ranged from enhanced baseball cards for the Little League World Series to a tour of the Klamath Falls Restoration Celebration.

Social media usage is well established, with personal accounts primarily used for non-work purposes

Not surprisingly, Facebook was the most popular social network for personal use. Only 66 respondents said they used their personal Facebook account “primarily” for work, whereas 201 predominantly use their personal account for non-work purposes.

A similar number, 199 respondents, have the ability to access their organization’s Facebook account. Just behind this, 145 participants told us that they had access to their organization’s Twitter account.

When looking at slightly newer social networks, the personal accounts of journalists on Instagram and Snapchat are overwhelmingly used for non-work purposes. Only five respondents told us their personal Snapchat accounts were primarily used for work. In contrast, 73 respondents said their personal Snapchat accounts were typically used for activity unrelated to their day jobs.

Local journalists want to know more about video and podcasting

A sizable number of respondents told us that they were eager to learn more about video reporting, live video, and podcasts. Interest in emerging platforms such as chat apps, augmented reality, and virtual reality, however, garnered much lower levels of interest.

Authors’ commentary: newer technologies still need to prove themselves

These findings are, perhaps, not surprising given the infancy of some of these new technologies. Tools such as chat apps and AR/VR are still finding their feet with journalists and audiences alike.

Moreover, fundamental questions about whether these platforms—especially augmented and virtual reality—can be adequately monetized are still being debated.33 There is also the wider question of the accessibility and popularity of these platforms with users.34

Given this, and the fact that small-market newsrooms cannot do everything,35 local titles need to use their resources wisely. It’s somewhat inevitable, therefore, that their focus will often gravitate toward more established digital formats.

Mainstream media platforms are also likely to be better understood—and used—by the older demographic that tends to consume local news. However, cutting-edge digital platforms may help to engage a younger audience.36

As one respondent explained:

I think a lot of small newspapers, along with newspapers of any size, struggle to reach younger audiences. Being 21 years old, I can see that newspapers struggle to reach my generation and those younger. I think we have to come up with unique and innovative ideas to keep them engaged.

Although the empirical research on this issue currently remains unconvincing,37 levels of interest within local newsrooms in these nascent digital tools and technologies may change over time. We believe that this is a space worth watching.

Trade press and self-learning are key for developing digital knowledge

Staff at small-market newspapers often needs to be resourceful in learning about industry developments and new digital tools.

According to our respondents, significant numbers of local journalists turn to articles published by the Niemen Journalism Lab,38 Poynter,39 MediaShift40 (80 percent), and/or teach themselves (75 percent) about new tools and technologies relevant to their work. Preference for these learning methods ranked far ahead of attending conferences (38 percent) or training courses (27 percent).

Metrics tools are becoming established tools in small newsrooms

Our final technology-focused question explored the use of metrics in local newsrooms. Chartbeat, Google Analytics, and the American Press Institute’s Metrics for News program41 are just some of the tools which have helped to deepen our understanding of audience’s digital habits. We were curious to see if use of these technologies—and metrics more generally—had permeated local newsrooms.

More than two-thirds (70 percent) of respondents told us their organization—or they themselves—use performance metrics to measure audience engagement. This included use of specific metrics software, capturing social media likes/shares/follows, website unique visitors, and engagement time/time on page.

These efforts are often top-down, although individual reporters told us they do follow their social media likes/shares/follows. Based on our sample, at an individual level, these metrics are the ones journalists are most likely to pay attention to.

Metrics are shaping storytelling at small-market newspapers

Of those organizations that make use of performance metrics, almost two-thirds (65 percent) said it influenced the way they produced a story “some of the time,” while 24 percent said it did “none of the time.”

Authors’ commentary: we want to know more about how metrics are used in smaller newsrooms

Performance metrics have become integral to editorial decisions across the industry in recent years.42 While some argue that metrics demonstrate the types of stories that readers read and want, perhaps making the news and information ecosystem more “democratic . . . where readers matter more than editors,” others worry about “a world where Kim Kardashian beats out more important subjects, like the Syrian conflict.”43

The fact is that metrics are here to stay. Their use across the spectrum of newspapers— from smaller titles, to major national and international outlets—means that discussions about the impact of metrics must be broadened to include stakeholders from across all tiers of the newspaper industry. Of these, the experience of smaller newsrooms is the area that is perhaps the least well understood, and thus worthy of further study.

Small-Market Newspapers and Engagement

Key points:

- Respondents offered us a variety of definitions for engagement

- Some saw this as an industry buzzword

- Others described engagement as the DNA of small-market newspapers

Engagement was arguably the media buzzword of 201644,45 as publishers moved away from scale and chasing large traffic numbers, toward an increasing focus on deepening their relationships with new and existing audiences.46

Reviewing the literature, from both academia and the industry, we see engagement defined as a philosophy, a practice, and a process.47 Some, for instance, define engagement as community building; others link it to the ability to remember and recall a story, while some—like Jake Batsell—note the role of engagement as a business practice.48

Because definitions of engagement can vary, we asked our survey respondents what engagement meant to them, and how they measured it.

Engagement is not necessarily a term local papers relate to

Although major metros and national outlets have just begun to embrace the importance of engagement in its myriad forms, small-market newspapers have long been closely connected (both offline and in their daily output) to their local community. Failure to do so, in many cases, would have been commercial suicide.49,50,51

Because of this, some respondents expressed frustration at our request for them to define “engagement.” Some participants felt that discussions on this topic were detached from the reality of needing to “get the paper out.” For many of these respondents, engagement is an empty industry buzzword and a label with little relevance for small-market newspapers.

Examples of responses we received from journalists in this camp included:

“Engagement is a five-dollar word dreamed up by overpaid consultants trying to sell newspapers on what they are already doing—reporting on the lives and concerns of everyday people in their communities.”

“Meaningless bullshit.”

“A meaningless term handed down by our clueless corporate overlords that no self-respecting journalist would use.”

Engagement is an established principle for many local newspapers

Others took a different view, highlighting how traditional forms of engagement such as letters to the editor, phone calls, and print readership continue to be popular.

One respondent said, “Engagement is something our paper never lost. Our readers primarily aren’t on social media beyond personal Facebook pages . . . We are still read, discussed, called, emailed, and written to. That’s all the engagement we really need.”

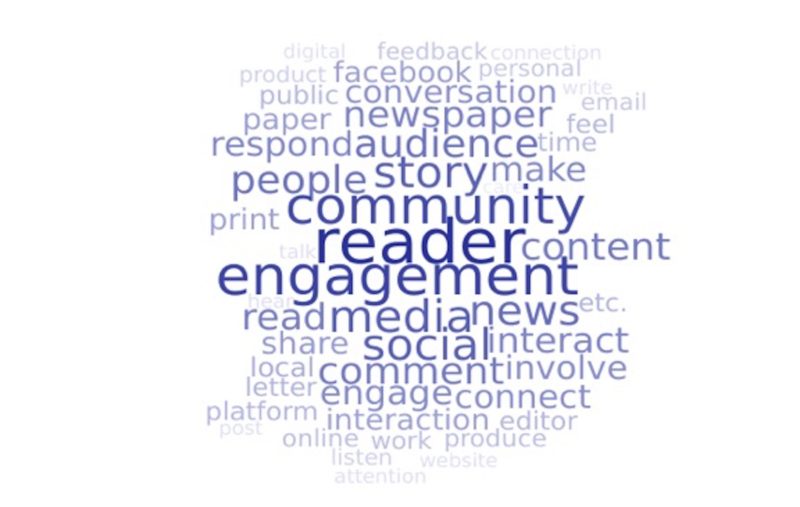

Word Cloud of Terms Used by Respondents to Define “Engagement”

Some participants explained engagement purely in terms of hard data

Further contributions to this question offered a different perspective. At its most basic level, engagement was sometimes described as a means to measure impact. Specifically, respondents attributed it as a way to provide hard numbers—such as readership figures, time on site, and other quantifiable data—of interest to both publishers and advertisers alike.

A typical response, in that vein, defined engagement as “ . . . a measurable level of reader input, data tracking, or feedback.”

Respondents identified many benefits to “engagement”

An additional group defined engagement as a term to describe the broader contract between a newspaper and its community. This contract has many constituent parts, with survey participants emphasizing different elements depending on their own philosophical standpoint and newsroom practices.

Some of the characteristics of engagement highlighted by this cohort include: building relationships, creating feedback loops, being part of the community, fostering conversations, and listening and engaging with audiences in a variety of places and spaces.

As one respondent noted, “To me, engagement means interacting with readers on a variety of platforms. Particularly on social media, it’s a way for readers to talk with and ask questions of their local reporters and vice versa, and hopefully build trust with them.”

This matters, several respondents observed, due to the importance of ensuring that audiences feel invested in the success of their community and its newspaper. Effective engagement also means that newspapers reflect the needs and aspirations of their readers.

Noted one survey participant:

Good engagement tells us what is interesting to readers, lets us immediately clarify or add to information in stories already published, gives us new story ideas, and when done right gives the reader/consumer a sense of ownership that “this is their news source,” in which they have a say and a voice.

The benefits of successful engagement can therefore be both economic (increased subscribers and readers), as well as more civically minded, helping to promote dialogue and create opportunities for community cohesion.

Authors’ commentary: it’s engagement whether you call it that or not

Many of the traits we categorize as “engagement” matter to small-market newspapers and have for some time. There’s a clear economic imperative for this: effective engagement helps to drive readers and subscribers—and with it the advertising dollars that are the lifeblood of local newspapers.

But our conversations, both within this survey and the wider, in-depth interviews we have undertaken, also show that for many journalists engaging audiences is at the heart of their beliefs around what local journalism is and should be about. Engagement is central to what many local titles already do, and what they have always done. Whether they choose to apply the “engagement” label to this or not is another matter.

The Future

Key points:

- 61 percent of respondents were “very positive” or “slightly positive” about the future of small-market newspapers

- Just over a third (34 percent) expressed the view that they were “slightly negative” or “very negative” about the future of their sector

- The size of small-market newspapers—embedded within the communities they report on—are seen as considerable assets, and sometimes we undervalue this

- Key challenges include resources, awareness, and attracting younger audiences

Finally, at the end of our survey, we asked respondents to share their views on how the industry might move forward. We used a series of open questions to ask about the opportunities and challenges facing the sector, while also exploring levels of optimism about the long-term health of small-market newspapers.

Local journalists are more positive about the future than you might expect

Pushing back against the popular narrative that the death of the newspaper industry is imminent,52 our respondents were predominantly optimistic about the future for small-market newspapers.

Across our sample, 61 percent of respondents selected “very positive” or “slightly positive” from the six options available to describe the future health of their industry. Only a small number of participants (7 percent) sat on the fence, declaring that they felt “neither positive nor negative” about the prospects for small-market newspapers.

In contrast, just over a third of respondents (34 percent) declared themselves to be “slightly negative” or “very negative” about the prospects for their industry.

Authors’ commentary: why were 61 percent of respondents positive about the future for local newspapers?

Considering the level of job losses and shuttered titles we have seen in the past decade, the optimism of our survey participants might come as a surprise. This finding, however, reinforced similar ones from our qualitative interviews, wherein many interviewees told us that they were cautiously optimistic about the future of their industry.

Industry experts and practitioners are sanguine about the prospects for small-market newspapers for a number of reasons, including: their ability to tell local stories which often go untold by other media, existing relationships with their community and subscriber base, heritage and longstanding reputation, and the ability to support local advertisers that are often too small or niche to be effectively served elsewhere.

Many of our survey respondents expressed similar views, suggesting that some small-market newspapers believe they are well placed to weather the digital storm. As one survey participant told us: “Small-market newspapers have great potential to succeed for many years to come. To use a cliché expression, they control their destiny. Small-market newspapers need to realize their potential and continue producing the best hyperlocal news for their communities that residents can’t get anywhere else.”

This sense of optimism echoes earlier studies and reports, which found that many small-market newspapers had arguably weathered the economic and authoritative crisis of journalism better than their metro counterparts.53,54,55,56,57

Challenges such as relevance, awareness, andcompetition abound

Of course, for all of the positivity and optimism we encountered, there are also very real challenges facing the sector. Examples of issues our respondents highlighted included: resources and revenues, attraction and retention of young audiences, recruiting young journalists, and a wider recognition and awareness of what small-market newspapers have to offer.

One respondent said, “We have noticed that many community members are unaware of community newspapers, sometimes because they’ve never experienced them before.”

The same respondent also noted that an increasing challenge, particularly in an age of social media and on-demand entertainment, is capturing the attention of audiences. “Time is a huge factor, too. Many people say they’re too busy to read a newspaper or do more than glance through headlines online. That’s a societal issue.”

The ownership structure of local newspapers can also be an issue for some outlets. Although many publications are independent, there are others that are part of larger chains. While this can help to unlock economies of scale for ad buys and technology (such as content management systems), it can also, at times, result in a uniformity which doesn’t allow for local flexibility.58

One respondent explained this dynamic from the perspective of their own paper:

Our newspaper has fewer than 5,000 readers. Our personal challenge is that the owners treat all papers the same, daily and weekly, when the challenges are very different. Personally, I think we are shooting ourselves in the foot at our paper by publishing our stories for free on our website, because we have no local competition. We are competing against our own print product with a free internet product that consumes staff time but doesn’t generate a lot of revenue.

Finally, we also saw a further acknowledgement of the challenges around trust and engagement, which permeate the industry as a whole. Noted one survey participant, “Many citizens also seem to be wary of reporters, even in a rural community. So any missed events just breed distrust as people take offense that things they are involved in aren’t being recognized in the publication.”

These concerns are part of a wider landscape of challenges identified by our survey respondents, which included: retaining advertisers, competing with citizen journalists, competing with social media, maintaining (and growing) readership, audience resistance to “paid” versus “ free” news, corporate ownership/leadership, credibility and competing with cynicism, an ever-increasing workload (even if working hours may be fairly stagnant), contending with the impact of national news outlets, and balancing a printed and digital product.

Many of these challenges are not unique to small-market, local newspapers. There are structural and economic challenges that radiate throughout the industry, but they manifest themselves differently—and to different extents—at each publication.

Opportunities

For many of our respondents, the secret sauce for small-market newspapers lies in the fact that they can provide a level of local reporting that other media simply cannot. “No other publications or electronic media offers readers the local coverage that a small newspaper can provide its community. The opportunity is there to succeed. The newspaper has to make the effort to find stories and to write quality work that readers will look forward to,” said one respondent.

In this regard, the causes for optimism many participants identified can also be seen as opportunities. Our respondents reported, for example, that their newspapers are often the only original news voice in a community—an observation that aligns with other industry observations.59 Others highlighted the strategic importance of doubling-down on ultra-local content and ensuring a broad spread of stories and people in their publication.

As one respondent recommended:

Be hyperlocal. Don’t be The New York Times or The Washington Post. Look to our past when small town papers ran everything happening locally, even social columns (which were essentially an early print version of social media).

Get off our high horse and be willing to cover the smallest event from time to time. Get local names/faces in the paper (and not just the same old ones that are in there every week).

This practical application was accompanied by a range of answers from respondents, which emphasized the benefits of small-market newspapers focusing on localness, trust, quality content, and developing real relationships with consumers and advertisers.

As several respondents observed, the size of small-market newspapers is an asset, not a weakness. Local journalists are physically and attitudinally close to the communities they cover, meaning that they are perhaps less likely than their counterparts at larger outlets to be detached from the hopes, aspirations, and experiences of their readers.

Noted one survey participant:

What makes small-market papers special is right there in the name—their size. I’ve worked at a variety of different papers, and smaller papers have the advantage of being more able to connect with readers because they are more well known around town. We run into readers in the coffee shops on a daily basis. They’re our neighbors. Our kids go to school with them.

And yes, this is true for journalists at larger papers, but somehow they feel more separate from the community as a whole. They are a more diluted population in a big city. But in our coverage area, our reporters have great byline recognition, and personal history and connection with people here. I think that counts for a lot.

Local journalists want us to stop portraying their sector so negatively

Finally, a challenge and opportunity for the sector which our survey identified is the need to change the conversation we are having about the future of local newspapers.

As a number of our respondents noted, the sector needs to stop talking itself down. Failure to do so means that the “doom and gloom” we project about the state of this industry risks becoming a self-fulfilling prophecy.

As one survey participant commented, “[Our] biggest challenge is a prevailing belief among readers that print is dying. People associate the bad news about the big dailies with smaller, community publications. They are different business models, and the community model is more sustainable. But the public is not aware of that.”

Another respondent agreed with this, saying, “We are allowing the naysayers to kill our industry. We still offer something unique which residents want, but we allow the screaming voices of gloom and doom to convince people that we are worthless.”

Authors’ comment: we can change the conversation paradigm

Journalists and researchers can play a role in changing the discussion about the future of small-market newspapers. They need to trumpet successes more clearly, highlighting examples of innovation and impact.

We also need to recognize that the master narrative of job losses and declines in advertising revenues masks a more complex, nuanced picture. Small-market newspapers are experimenting with storytelling formats, identifying new ways to measure and embrace engagement, and using metrics to guide elements of their work.

Reflecting this creative reality and the community impact small-market newspapers continue to have should not be overlooked. Of course, new and emerging digital technologies, changes in consumer behaviors, and the prevailing economic conditions for the sector cannot be ignored. But small-market newspapers are part of a more subtle, sophisticated, and multifaceted landscape than most people realize. Industry leaders and researchers should not shy away from portraying this complexity. We look forward to being part of that conversation.

Conclusion

This report sheds light on a key segment of the newspaper industry that all too often gets overlooked in wider conversations and analysis: small-market newspapers.

While some of the results from this indicative survey correlate with what we know about the newspaper industry as a whole—long work hours, decreased newsrooms, an increased focus on digital output—other results offer a different perspective.

For example, our respondents suggested that working hours for most newsroom employees have remained relatively consistent over the past two years. This finding surprised us, given the reality of smaller newsrooms and the pressure to produce more stories. Similarly, we learned that despite the apparent “doom and gloom” around the wider newspaper industry, more people feel secure in their jobs than might be expected.

We also learned how newsroom staff, specifically reporters and editors, make use of digital tools, how they learn about new technologies, and how they develop digital skillsets. Much of this is through reading the industry press and self-learning. There may be an opportunity here to help bridge this gap through more formal support mechanisms.

Alongside this, we also heard about how recruiting and retaining young journalistic talent is a significant challenge. This may become a demographic time bomb for the industry if issues of pay, workload, and career development are not addressed in the future.

Despite this key challenge—and the ever-present issues of being short on time and money—a major takeaway from this survey is the level of optimism at small-market newspapers. This mirrors a similar sense of hope that we encountered during the qualitative interviews with local journalists and editors we conducted in late 2016.

A commitment to localism, local news, and their communities, coupled with a slower rate of change than is happening in major metro markets, has allowed many smaller newspapers to emerge in better health their larger cousins.

Smaller-market newspapers can also benefit from sometimes being the only source of original reporting in a community. This, along with the longevity that many publications have already enjoyed, can help many outlets hold on to and even reaffirm valuable, long-term relationships with readers, community leaders, and advertisers. These are the finer details that we can easily miss if we consider the newspaper industry as a monolithic sector that ebbs and flows at the same pace.

Our research joins other recent reports focusing on specific local newsrooms and news ecologies across the country such as those by the Local News Lab in New Jersey,60 the Center for Innovation and Sustainability in Local Media in North Carolina,61 and the Duke Reporters’ Lab.62

Our results encourage us to more effectively nuance the conversation about the crisis of journalism and the death of newspapers. Of course, there are economic concerns for small-market newspapers, and respondents were not shy about sharing those. But there are other stories to be told, too.

We hope that this survey and its results will help kick-start a renewed focus on small-market newspapers among industry watchers and researchers. This conversation should not overlook the very real challenges being faced at all levels of this industry; however, at the same time it must also celebrate the opportunities and successes present within this still vitally important news medium.

Acknowledgments

Our thanks to everybody who made this report possible, in particular the 400-plus local journalists from across the United States who generously shared their thoughts and experiences with us. This study would not have been achievable without these insights, and we hope you find them as interesting as we do. Thank you also to the organizations that promoted and encouraged participation in this survey. You helped us to reach and engage with participants beyond our own networks, and this paper is all the richer as a result.Of course, this project would not have been possible without the support of a number of institutions, including the Tow Center for Digital Journalism at Columbia University, our transcribing team and citations editor, the University of Oregon, the University of Virginia, and Columbia University. At Tow, we want to extend our thanks to Emily Bell, Claire Wardle, Elizabeth Hansen, Kathy Zhang, and Nausicaa Renner. Throughout this process you’ve given us invaluable feedback, encouragement, and support. The Tow Center and Columbia University also made it possible for Rosalind Donald to work with us on this project.We are grateful for the help of the Scribe Collective and Kathy Talbert at D-J Word Processing for their transcribing prowess, and to Sheila Bodell for formatting all of our citations.The University of Oregon kindly hosted our survey, and also enabled Thomas Schmidt to work with us on the early stages of this survey. During the summer of 2016, when this project began, Damian’s involvement was made possible by a grant from the Agora Journalism Center, the gathering place for innovation in communication and civic engagement, at the University of Oregon’s School of Journalism and Communication.Our thanks as well to the University of Virginia for its support and encouragement around Christopher’s research interests.

—Damian Radcliffe and Christopher Ali, with Rosalind Donald, May 2017

Appendix: Online Survey Questionnaire

Hello. Thank you for clicking on a link to take this short survey. This questionnaire explores what it is like to be a local newspaper journalist in 2016.

We believe local journalism matters, and this research aims to shed light on the experiences and needs of people working at newspapers with a circulation below 50,000 readers.

It’s part of a wider project exploring local newspapers, innovation, and engagement that is being conducted under the auspices of the University of Virginia (project # 2016-0227-00) and the University of Oregon (project # RCS 06062016.010), and supported by the Tow Center for Digital Journalism at Columbia University.

The survey is entirely optional and will take approximately 10–15 minutes.

The data we are asking for will be anonymous in the final report. While we do ask that you consider providing us with the name of your publication, this information will not be linked to any of your answers. It will, however, help us better understand the breadth and reach of our survey.

There is no risk to participating in this survey and you are free to withdraw at any time by simply exiting your browser. You may also skip questions you do not wish to complete.

By taking this survey, you consent to us using your answers to inform our research. If you would like to see a copy of our report, when published, you can leave your email address at the end of the survey. Your name, email, and newspaper will not be linked to any conclusions from this data that we will publish.

Thank you for taking the time to tell us your experiences. If you have questions about the survey, contact either of the principal investigators:

Christopher Ali, Ph.D. Assistant Professor Department of Media Studies University of Virginia cali@virginia.edu 267-582-0022

Damian Radcliffe Carolyn S. Chambers Professor in Journalism School of Journalism and Communication University of Oregon

damianr@uoregon.edu 541-346-7643

Before we start, please tell us a little bit about yourself.

- What is your primary job function?

- Editor (Section/Managing)

- Reporter

- Digital/Social Media (editorial side)

- Technology/Product

- Sales/Business Development (print)

- Sales/Business Development (digital)

- Other (please state)

- Editor (Section/Managing)

- How old are you?

- 18–30

- 31–49

- 50+

- Prefer not to say

- 18–30

Topic 1: Experience and Role

- How long have you been working in local media?

- Less than a year

- 1–4 years

- 5–9 years

- 10–19 years

- 20 years+

- Decline to say

- Less than a year

- Do you mostly work:?

- On the print product (i.e., physical newspaper)

- On the digital product (e.g., social, website, etc.)

- I split my time across the two

- Decline to say

- Other (please specify)

- On the print product (i.e., physical newspaper)

Topic 2: Changes in Output

- Thinking about your work over the past two years, how has the focus of your output changed? Consider the hours, demands, tasks, and expectations for your role.

- Increased

- Stayed the same

- Decreased

- Don’t know/decline to say

- Not applicable

- Thinking back to two years ago, has the number of stories you personally produce:

- Increased

- Stayed the same

- Decreased

- Don’t know

- Increased

Topic 3: Working Hours

- How many hours a week do you work on average? (Open question)

- Thinking back to two years ago, have these hours:

- Increased

- Stayed the same

- Decreased

- Don’t know

- Increased

Topic 4: Job Security

- Compared to two years ago, has the number of people at your publication:

- Increased

- Stayed the same

- Decreased

- Don’t know

- Increased

- How secure do you feel in your job?

- Very secure

- Slightly secure

- Neither secure or insecure

- Slightly insecure

- Very insecure

- Don’t know/Decline to say

- Very secure

Topic 5: Industry Changes

- Local journalism is going through a period of change and facing a number of challenges. To what extent do you feel you understand your organisation’s business strategy?

- Fully understand

- Understand a little

- Neither understand or don’t understand

- Don’t understand

- Fully understand

Topic 6: Social Media

- What social media platforms do you use? [Use means actively post to the account not simply have administrative access to] (Please select all that apply)

- Personal account– mainly used not for work

- Personal account– used mainly for work purposes

- Your news organization’s account Facebook

- Twitter

- Instagram

- Snapchat

- YouTube

- Tumblr

- Slack

- Other

- Twitter

- Personal account– mainly used not for work

Topic 7. Innovation, Skills, and Professional Development

- Do you use any of the following at your publication? (Tick all that apply)

- Video reporting

- Live Video (e.g., Facebook Live, Periscope)

- Podcasts

- Chat Apps (WhatsApp, Kik etc.)

- Augmented Reality

- Virtual Reality

- Video reporting

- How interested are you in using or learning about these emerging formats? 1 = Not interested 5 = Very interested

- Video Reporting

- Live video, e.g., Facebook Live, Periscope

- Podcasts

- Chat apps

- Augmented reality

- Virtual reality

- Video Reporting

- How do you learn about new technology and tools related to your industry? (Tick all that apply)

- Articles (e.g., in Nieman, Poynter, MediaShift, etc.)

- Training course paid by my employer

- Conferences

- Self-taught

- Other

- Not applicable

- Articles (e.g., in Nieman, Poynter, MediaShift, etc.)

Topic 8: Engagement

- Engagement is the big buzzword of 2016. What does engagement mean to you? (Open question)

Topic 9: Metrics and measurement

- Do you—or your newspaper—use metrics to measure audience engagement?

- Yes

- No

- Yes

- If yes, tick all that apply:

- Personally use/ measure

- Organization uses/ measures

- Don’t know

- Metrics software,e.g., Chartbeat, Google Analytics, Metrics for News.

- Social media likes/shares/follows

- Website unique visitors

- Engagement time/ time on page

- Open rate (for newsletters)

- Attendance at events

- Print and digital subscribers

- Number of members/donors

- Other

- Personally use/ measure

- Do key performance metrics influence the way you produce a story:

- All the time

- Most of the time

- Some of the time

- None of the time

- Prefer not to answer

- All the time

Topic 10. Future of Journalism

- How positive do you feel about the future of local newspapers? (Select one)

- Very positive

- Slightly positive

- Neither positive nor negative

- Slightly negative

- Very negative

- Don’t know

- Very positive

- We recognize that money and time are scarce resources for newspapers in the digital age. Aside from these two factors, what is the biggest challenge facing small-market newspapers? (In our study we’re defining this as publications with a circulation below 50,000 daily readers) (Open question.)

- What is the biggest opportunity for small-market newspapers? (Open question.)

Thank you for taking the time to respond to this questionnaire.

Please, can you answer three final questions about your publication? None of your answers from this survey will be attributable to you, or your newspaper.

- What is the title of your publication?

- ________ (Fill in the blank)

- Prefer not to say

- ________ (Fill in the blank)

- Where is your publication located?

- Zip Code

- How would you characterize the ownership of your paper:

- Owned by a national newspaper chain (e.g., Gannett/Hearst)

- Owned by a regional newspaper chain (e.g., Shaw)

- Owned by a hedge fund/non-journalism company (e.g., Berkshire Hathaway)

- Locally/community-owned

- Family-owned

- Other (please specify)

- Don’t know

- Owned by a national newspaper chain (e.g., Gannett/Hearst)

If you would like us to send you a copy of our report when it is published, then please enter your email address here:

Many thanks.

Citations

- Editor & Publisher, “E&P’s Searchable Online Newspaper Database,” 2014,https://www.editorandpublisher.com/databook/.

- Benjamin Mullin, “Local News Is in the Fight of Its Life. Here’s How We’re Covering the Story.,” Poynter, February, 2017, https://www.poynter.org/2017/local-news-is-in-the-fight-of-its-life-heres-how-were-covering-the-story/448601/.

- Michael Barthel, “Newspapers: Fact Sheet,” Pew Research Center, June 15,2016, https://www.journalism.org/2016/06/15/newspapers-fact-sheet/.

- CareerCast.com, “The Worst Jobs of 2016,” CareerCast, 2016, https://www.careercast.com/jobs-rated/worst-jobs-2016.

- Art Swift, “Americans’ Trust in Mass Media Sinks to New Low,” Gallup,September 14, 2016, https://www.gallup.com/poll/195542/americans-trust-mass-media-sinks-new-low.aspx.

- Amy Mitchell, Jeffrey Gottfried, and Michael Barthel, “The Modern NewsConsumer: Trust and Accuracy,” Pew Research Center, July 7, 2016, https://www.journalism.org/2016/07/07/trust-and-accuracy/.

- Michael Barthel, Amy Mitchell, and Jesse Holcomb, “Many Americans Believe Fake News Is Sowing Confusion,” Pew Research Center, December 15, 2016,https://www.journalism.org/2016/12/15/many-americans-believe-fake-news-is-sowing-confusion/.

- Media Insight Project, “The Personal News Cycle: How Americans Chooseto Get Their News,” American Press Institute, March 17, 2014, https://www.americanpressinstitute.org/publications/reports/survey-research/personal-news-cycle/.

- Amy Mitchell and Jesse Holcomb, “State of the News Media 2016,” PewResearch Center, June 15, 2016, https://www.journalism.org/2016/06/15/state-of-the-news-media-2016/.

- Laura Hazard Own, “A Neighbor Is Better Than a Newspaper: A Lookat Local News Sources in Rural Western Mountain Communities,” NiemanLab,May 19, 2016, https://www.niemanlab.org/2016/05/a-neighbor-is-better-than-a-newspaper-a-look-at-local-news-sources-in-rural-western-mountain-communities/.

- Seth C. Lewis, Kelly Kaufhold, and Dominic L. Lasorsa, “Thinking AboutCitizen Journalism,” Journalism Practice, no. 2 (2010): 163–179, https://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14616700903156919.

- Penelope M. Abernathy, “The Rise of a New Media Baron and the EmergingThreat of News Deserts,” July 8, 1905, https://newspaperownership.com.

- Christopher Ali and Damian Radcliffe, “In These Uncertain Times, LocalNewspapers Are More Important Than Ever,” Tow Center on Medium, November 14, 2016, https://medium.com/tow-center/in-these-uncertain-times-local-newspapers-are-more-important-than-ever-617258f8f483#.cnd8rsm2v.Tow Center for Digital Journalism86 Virtual Reality Journalism

- Mark Stencel, Bill Adair, and Prashanth Kamalakanthan, “The Goat MustBe Fed,” May, 2014, https://www.goatmustbefed.com.

- Caitlin Johnston, “Newspaper Reporter Is ’Worst Job’ in 2013, Study Says,”Poynter, April 23, 2013, https://www.poynter.org/2013/newspaper-reporter-is-worst-job-in-2013-study-says/211353/.

- Roy Greenslade, “Journalists Work Many Hours Beyond Contract,” TheGuardian, November 22, 2006, https://www.theguardian.com/media/greenslade/2006/nov/22/journalistsworkmanyhoursbe.

- Melody Kramer, “When Journalists Take a Vacation, Do They ActuallyTake a Break?” Poynter, July 8, 2015, https://www.poynter.org/2015/when-journalists-take-a-vacation-do-they-actually-take-a-break/355883/.

- Scott Reinardy, Journalism’s Lost Generation: The Un-doing of U.S. News-paper Newsrooms (New York: Routledge, 2017).

- Barthel, “Newspapers: Fact Sheet.”

- Alex T. Williams, “Employment Picture Darkens for Journalists at DigitalOutlets,” Columbia Journalism Review, September 27, 2016, https://www.cjr.org/business_of_news/journalism_jobs_digital_decline.php.

- Kristy Hess and Lisa Waller, Local Journalism in a Digital World (NewYork: Palgrave, 2017), 156.

- Bob Franklin, Local Journalism and Local Media: Making the Local News(New York: Routledge, 2006).

- Poynter, https://www.poynter.org/2015/new-study-finds-millennials-are-strong-news-consumers-but-take-an-indirect-path/327033/.

- Sharon Knolle, “Despite ’Doom and Gloom,’ Community Newspapers AreGrowing Stronger,” Editor & Publisher, June 1, 2016, https://www.editorandpublisher.com/feature/despite-doom-and-gloom-community-newspapers-are-growing-stronger/.

- Stencel, Adair, and Kamalakanthan, “The Goat Must Be Fed.”

- Penelope M. Abernathy, Saving Community Journalism (Chapel Hill: Uni-versity of North Carolina Press, 2014), https://www.savingcommunityjournalism.com.

- Margaret Rouse, “Augmented Reality (AR),” WhatIs.com, February, 2016,https://whatis.techtarget.com/definition/augmented-reality-AR.

- USC Annenberg, “AR Journalism,” Tumblr, https://arjournalism.tumblr.com/.

- Margaret Rouse, “Virtual Reality,” WhatIs.com, May, 2015, https://whatis.techtarget.com/definition/virtual-reality.

- Caleb Garling, “Virtual Reality, Empathy and the Next Journalism,” Wired,November, 2015, https://www.wired.com/brandlab/2015/11/nonny-de-la-pena-virtual-reality-empathy-and-the-next-journalism/.

- Patrick Doyle, Mitch Gelman, and Sam Gill, “Viewing the Future? Vir-87tual Reality in Journalism,” Knight Foundation, March, 2016, https://www.knightfoundation.org/media/uploads/publication_pdfs/VR_report_web.pdf.

- Gerry O’Brien, “Try ‘Augmented Reality’ to Relive the Series,” The Herald and News, August 16, 2015, https://www.heraldandnews.com/sports/baberuth/try-augmented-reality-to-relive-the-series/article_3d8276dc-6d21-5e09-a670-cde56150d2c8.html.

- Anusha Alikhan, “Virtual Reality in Journalism: New Report Provides anOverview of a Growing Platform for Storytelling,” Knight Foundation, March 13,2016, https://www.knightfoundation.org/press/releases/virtual-reality-journalism-new-report-provides-ove.

- Ibid.

- Gerry O’Brien, “Tell Us What You Think,” The Herald and News, November 21, 2015, https://www.heraldandnews.com/news/tell-us-what-you-think/article_c9fcf65c-13ee-5fac-bc70-a61887e6ecef.html.

- Catalina Albeanu, “Could Virtual Reality Get Young People More En-gaged with News?” Journalism.co.uk, June 18, 2015, https://www.journalism.co.uk/news/could-virtual-reality-get-young-people-more-engaged-with-news-/s2/a565511/.

- Jaana Hujanen and Sari Pietikainen, “Interactive Uses of Journalism: Cross-ing Between Technological Potential and Young People’s News-Using Practices,”New Media & Society, no. 3 (June 1, 2004), https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/1461444804042521.

- NiemanLab, https://niemanreports.org.

- Poynter, https://www.poynter.org/.

- Mediashift, https://mediashift.org.

- Metrics for News, https://www.metricsfornews.com.

- Federica Cherubini and Rasmus Kleis Nielsen, “Editorial Analytics: HowNews Media Are Developing and Using Audience Data and Metrics,” ReutersInstitute for the Study of Journalism, https://digitalnewsreport.org/publications/2016/editorial-analytics-2016/.

- Alexis Sobel, “When Metrics Drive Newsroom Culture,” Columbia Journal-ism Review, May 11, 2015, https://www.cjr.org/analysis/how_should_metrics_drive_newsroom_culture.php.

- Ben DeJarnette, “4 Ways to Make Engagement Journalism Sustainable,”MediaShift, January 21, 2016, https://mediashift.org/2016/01/4-ways-to-make-engagement-journalism-sustainable/.

- Lois Beckett, “Engagement: Where Does Revenue Fit in the Equation?”NiemanLab, October 28, 2010, https://www.niemanlab.org/tab/engagement/.

- Damian Radcliffe, “Five Reasons Why Engagement Is So Hot Right Now,”The Media Briefing, January 3, 2017, https://www.themediabriefing.com/article/five-reasons-why-engagement-is-so-hot-right-now.Tow Center for Digital Journalism88 Virtual Reality Journalism

- Jake Batsell, Engaged Journalism: Connecting with Digitally EmpoweredNews Audiences (New York: Columbia University Press, 2015), https://cup.columbia.edu/book/engaged-journalism/9780231168342.

- Ibid.

- Judy Muller, Emus Loose in Egnar (Lincoln, NE: University of NebraskaPress, 2012), https://www.nebraskapress.unl.edu/product/Emus-Loose-in-Egnar,674809.aspx.

- Jock Lauterer, Community Journalism: Relentlessly Local (Chapel Hill:University of North Carolina Press, 2009), https://uncpress.unc.edu/books/T-7751.html.

- Abernathy, Saving Community Journalism.

- Joran Kurzweil, “Print Is Dead! Long Live Print?” February 25, 2012, https://techcrunch.com/2012/02/25/print-is-dead-long-live-print/.

- Diana Reese, “In Small Towns with Local Investment, Print Journalism IsThriving,” Al Jazeera America, April 29, 2014, https://america.aljazeera.com/articles/2014/4/29/newspapers-localownership.html.

- Knolle, “Despite ’Doom and Gloom,’ Community Newspapers Are GrowingStronger.”

- John Jewell, “Regional Newspapers Are Starving to Death but Can LocalJournalism Survive?” The Conversation, August 4, 2016, https://theconversation.com/regional-newspapers-are-starving-to-death-but-can-local-journalism-survive-

- “Small Newspapers Handling Downturn Better,” Associated Press, August 9,2009, https://www.nbcnews.com/id/32350027/ns/business-us_business/t/small-newspapers-handling-downturn-better/.

- Geoff McGhee, July 14, 2011, https://web.stanford.edu/group/ruralwest/cgi-bin/drupal/content/rural-newspapers.

- Penelope M. Abernathy, The Rise of a New Media Baron and the EmergingThreat of News Deserts (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2016),https://www.uncpress.unc.edu/browse/book_detail?title_id=3902.

- Abernathy, “The Rise of a New Media Baron and the Emerging Threat of News Deserts.”

- Local News Lab, https://localnewslab.org.

- Abernathy, Saving Community Journalism.

- Reporter’s Lab, https://reporterslab.org.

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.