The news industry is full of ideas when it comes to experimenting with new storytelling formats and techniques—podcasts, virtual reality, Instagram posts. The list is long, but storytelling across these media and platforms is something the journalism-adjacent advertising industry has been experimenting with for decades. Complex ad-measurement metrics now demonstrate, in granular detail, the effectiveness of traditional advertisements. The rapid adoption of those metrics across the ad industry has forced news organizations to defend how they manage their ad businesses. Publications old and new have to justify the effectiveness of advertisements they create or distribute for clients. This relationship has forced many publications to reimagine their business models as they continue to transition from print to digital.

Newspapers were once able to charge hundreds of thousands of dollars for a single full-page print ad, but as readers abandoned their print subscriptions in favor of digital news, many advertisers realized they were no longer reaching the same large audiences in print. Meanwhile, new digital media began to flourish in the ad-supported digital ecosystem. However, the conventional banner, pre-roll, and pop-up advertising that could be measured for effectiveness was found wanting, to put it mildly—AdAge has described click-through rates on these units as “abysmal.”

Enter native advertising: Native ads take on the appearance of real news stories, and are crafted by people inside news publications who want to create and spread commercial messages that don’t look like traditional advertisements that overtly push product. This report clearly outlines how news outlets produce native advertising and how this practice borrows credibility from the newsroom in order to enhance the value of the ad created for clients.

Native advertising has been found to deceive readers. Journalists know this. Ultimately, the trust they work hard to secure may be jeopardized by the creation and dissemination of native advertisements.

Executive Summary

Native advertising is not an entirely new concept; in fact, it bears a striking resemblance to the product public relations firms sell. PR firms routinely pitch journalists story ideas that make their client’s products and services look good. There is more than one difference between ads and PR, but one is key for our purposes here: news publishers don’t earn any advertising revenue if their reporters decide to write on a topic a public relations firm told them about. Native advertising enables news publishers to charge brands for work that has traditionally been performed by PR firms.

This development has created an intimate relationship between brands and news publishers—one that deserves careful examination. After a series of over thirty interviews with people who sell, write, produce, and distribute native advertising, a few important themes bubbled to the surface.

Key Findings:

- Native ads borrow the credibility and authority of their respective news publishers. A former employee of the T Brand Studio, The New York Times’s branded content division, said the studio tries to create native ads that are “Times-ian.”[1]This notion—creating content that is in the same tone as a publication’s newsroom—was repeated on several occasions by people working across several news titles.

- Clients have significant negotiation power. News publishers compete with each other for advertising revenue and this environment gives marketers an upper hand when they negotiate the terms of a native campaign. One phrase came up in over half the interviews with people with work experience at branded content studios: clients, our interviewees constantly told us, always ask for something that “has never been done ”[2] The demand for novelty forces news organizations to pitch campaigns that are closely aligned with what journalists are producing, because other marketing channels can’t offer their clients this association. Selling partnerships with journalists was once considered unethical. Partnerships that would not have been possible in 2012 are now becoming standard practice, as clients can point to a new and unusual partnership with another publisher the previous year. The power imbalance means we may be in a race to the bottom when it comes to pushing back on how advertisers can and should work with new outlets.

- Transparency is only part of the solution. Regulation managing how news publishers work with clients is needed. Otherwise, advertisers can continue to pit news outlets against one another, ultimately sacrificing the quality of news coverage placed in front of readers. One employee who worked inside The Atlantic’s branded content studio said “publishers actively work with brands that are antithetical to their mission,” citing a partnership between the magazine and the Church of Scientology. The employee went on to explain how the publisher actively pitched advertisers branded content that was visible on the homepage of The Atlantic’s website.[3]

Methodology

The purpose of this report is to outline how advertisers work with news publishers. Properly unpacking this relationship required conducting a series of 32 interviews with people who work inside branded content studios. A mix of legacy publications and digital-only websites were included in this study because we believe both are crucial to a full understanding of how news publishers deal with this market.

This diverse set of companies included: The New York Times, The Atlantic, The Washington Post, Conde Nast, ATTN:, and BuzzFeed. Secondary sources were also vital to a full picture of the trend’s adoption across the industry. These sources come from a literature review of publicly available press pieces, academic texts, and ad industry handbooks that deal with native advertising, cited throughout.

The research was driven by a standard set of questions, asked of each interviewee: What’s the relationship between journalists and advertisers at your organization? Has it changed? How are native ads pitched? Who helps make them? How are they labeled? Who decides? What do clients ask for? How do you negotiate the terms of a branded content campaign?

These questions are meant to provide readers, journalists, and students with a clear understanding of the ethical challenges emerging inside news organizations today. After outlining how native advertising gets pitched and created, this guide aims to show news workers how to navigate the interests of the business side of a news organization without sacrificing their journalistic integrity. As for news readers, I hope this report encourages careful review of the articles that whiz by us, because they may be shaped by commercial interests that have the potential to conflict with the publication’s duty to its readers.

Introduction: Why Are Publishers Making Native Ads?

Today, native advertising is the central digital revenue stream for the publishing industry. It makes up some 60% of the market, or $32.9 billion, according to a 2018 forecast by market research firm eMarketer. Understanding why the trend has taken off with such speed requires a fuller appreciation of the changes that have shaped our overall information environment.

How we choose to spend our time means weighing trade-offs: What should we do right now? And what are we comfortable missing? In economics this trade-off is referred to as opportunity cost: Every time we make a choice, a cost is incurred—the loss of the second best choice. Tim Wu, a professor of law at Columbia University, expanded on this concept in his book The Attention Merchants, in which he posits that time has become a commodity in large part because we have so many options when it comes to deciding how to spend it.[4]

Wu says that today we live in an “attention economy.” An abundance of media channels provide us with more choices, meaning producers of content—from journalists to lawmakers—must work harder to secure the increasingly scarce resource of attention. News publishers compete for attention alongside everyone else. As a consequence of this newly widened media landscape, legacy news publishers are no longer able to exclusively capture ad revenue at the same scale, and with the same ease, as they were when print was their primary medium. Before the explosion of digital platforms, marketers relied heavily on print newspapers. There were neither browser extensions to hide the ads nor “engagement metrics” ostensibly guaranteeing that an ad had been “delivered” to a reader’s eyeballs. One print ad used to reach a large and captive audience: The New York Times first passed the million-copy mark for its daily edition’s circulation in 1985; in 2015 the print edition hovered around 625,000.[5]

As profits from traditional forms of advertising continue to shrink, digital “display” ad formats—the boxes of text, images, or video that sit at the top of a given page, called “banners,” and the boxes that cover content until you dismiss them, called “pop-ups”— have not replaced the lost revenue. According to Smart Insights, an advertising measurement platform, these units have an average “click-through” rate of only .05 percent. [6]

Worse, the number of times an ad has been shown to a potential customer—which retroactively determines the price of the ad— is often over-reported. Data suggest people don’t view them and that many of the clicks are accidental. The public also gets irritated by ads that pop up and auto-play video because they interrupt the reading experience.[7] Hence, ad-blocking technology is extremely popular and effective. Thirty percent of internet users are using some type of ad blocker.[8]

Branded content has seemed like a perfect solution. For one, it has none of the many drawbacks of digital display ads. The goal of branded content is not to distract, irritate, or annoy, but rather to engage people. The jargon around this concept can get confusing because branded content and native advertising are often used interchangeably, but they represent two different functions: Branded content is the word used by the ad industry to describe the type of content they are either making or buying. Chris Rooke, senior vice president of strategy and operations at the native advertising production company Nativo, explained in an interview that branded content is made with the intent to affect “consumer perception, affinity, and consideration.”

What distinguishes branded content from traditional TV spots or print ads is that the “content” attempts to deliver something its target audience will recognize as valuable. This might take the form of original reporting on a news website, or a compelling narrative around a product instead placing a brand at the center of a story. In contrast to digital display ads, value in branded content is defined by its non-interruptive nature and the way it provides people with content they might choose to see because it is entertaining or informative.

Native advertising simply refers to the placement of branded content. When branded content appears in a form that mimics the appearance of where it is placed, it becomes native advertising. For example, a native ad that is published on a news publisher’s website will take on a similar visual aesthetic and writing tone as the publication. It may use the same font as the publisher’s newsroom, it certainly shares the same URL, and depending on the publisher it may share imagery or pictures with the newsroom.

Branded content created by an advertiser and uploaded to that advertiser’s YouTube channel is not native. YouTube is not lending its logo to the advertiser, it is simply hosting another entity’s content. But, if an advertiser pays someone to create branded content on their behalf, like an influencer, then the content would be considered native advertising because it is in the influencer’s tone of voice, or mimics their aesthetic.

Over the past decade, numerous news publishers have created branded content departments. Native advertising not only mimics news content in appearance, but it is also delivered through the same platform, and allows for the same interactive elements. Branded content departments are tasked with selling original marketing to advertisers by guaranteeing reader engagement with content (text, video, podcasts, etc.) Engagement in this context is defined by time spent on page, video views, or scroll depth. The business model of selling native ads is so lucrative that many respected news publishers have invested in the trend. The New York Times opened T Brand Studio (disclosure: I worked in T Brand from the fall of 2015 to the spring of 2017); The Atlantic has Re:Think; BBC hosts Storyworks; and Condé Nast has tried to position 23 Stories as a stand-alone agency. Native advertising is predicated on a newspaper’s ability to translate the storytelling credibility of its newsroom to the publisher’s advertising department, even though it remains largely separate from the newsroom.

Publishers are well suited to making native ads because their newsrooms already create stories that millions of people read every day. A newspaper’s advertising department claims to be able to do the same thing for clients, especially and explicitly if it has branded content studio. The New York Times‘s native advertising department, T Brand Studio, marketed its services with the slogan “Stories that influence the influential.”6 The explainer video on T Brand’s website emphasizes the newsroom’s role in inspiring the studio’s branded content. The video features vignettes that shift back and forth between images of news articles—created by Times journalists— and images of native ads produced by T Brand for clients. The video was created to attract advertisers, not to explain how The Times actually creates native ads. It shows the finished product, advertisements, and compares it to the work of the organization’s newsroom.

Who Makes Native Ads?

News organizations were never structured to create original advertisements for clients. Publishers were simply distribution platforms. The advertising department inside a news publisher used to be filled, almost entirely, by salespeople. Success was defined by the thickness of a magazine, because that meant the issue attracted a lot of advertisers. Advertising agencies and clients were on the other side of the process. They gave salespeople the commercial messages they wanted readers to see. Traditionally, advertising agencies worked directly with brands to produce original commercial content. When the news industry realized it had to offer advertisers something besides distribution—native advertising—to remain profitable, the first task was obvious: they had to hire people who could make ads.[9]

More than a quarter of the people I interviewed first found their job inside a branded content studio because the job title matched what they were searching for when looking for open positions in the advertising industry. Every publisher in this study created new job titles: Creative Director, Strategist, Video Producer. These job titles had never existed in news publishing before; they were the terms advertising agencies used. Entire departments inside ad agencies are filled with strategists and video producers.

The new job titles spoke clearly to ad industry veterans who might be seeking open positions inside news organizations. Clare Stein is now the creative director of a digital publisher (ATTN:) and she had this exact experience when she made the decision to leave advertising to join The New York Times in 2014. Stein was hired as the first creative media strategist at the Times. She sat within a department called Sales Development. Prior to joining the paper she worked as a copywriter at Vayner Media. Stein found the job through LinkedIn while she had her filters set to look for open positions in the advertising industry.

When I interviewed Stein after she left the Times, she reflected on the experience, “In hindsight, I was probably naive about what a shift to a publisher would mean… I didn’t quite understand the realities of working at a publisher.”[10] Her statement is indicative of the drastic cultural change the paper was undergoing during her time there. The Times craved the perspective and experience of advertisers; the organization wanted Stein’s expertise to rub off on salespeople who were used to selling ad space. The new positions introduced valuable marketing skills to the sales department. News outlets never had to hire creatives, art directors, or copywriters. For the most part, they looked toward the ad industry’s job descriptions to craft their own recruitment materials. This cultural shift was actually made explicit in the Times’ leaked 2014 innovation report, which stated that the paper needed to change titles to attract fresh talent, and acknowledged that “Digital staffers want to play creative roles, not service roles.”[11] Previously, Stein’s position had fallen under the title “sales support.” When she said she didn’t realize what a transition into publishing would mean, she was referring to the fact that while the Times had changed some of its job titles, its sales-first culture had not changed.

Lisa Harvey is a salesperson who has worked at The Atlantic and The New York Times; she was able to shed light on just how much has changed between 2015 and our present moment. “For me it went from something that was quite simple— a sale (such as) a straight print buy, or media plan… (to) ‘What kind of story do you want to tell?’”[12] In 2016, “It was like I had a different job. It was like they were speaking a different language.” Harvey’s experience was the same at both companies: the sales job was no longer selling space; she had to become a story-seller. Every salesperson I spoke with said they were selling ideas or stories now.

After publishers staffed up to handle the demands of producing branded content, the challenge became organizing the ways native ads would actually be produced. Vox, the Times, and The Atlantic created new product teams. These teams acted as liaisons between branded content studios and newsroom employees. People on product teams work closely with editors and reporters to see what projects they are working on and try to find ways to align advertisers with upcoming newsroom content.

One Linkedin page captured a trend I was seeing across the profiles of many product managers who work for news organizations. As one of their accomplishments, a product manager at a prominent magazine lists, “Partnered with editorial and marketing leadership to plan special projects and map out editorial/product calendar.” This description may sound like jargon to the average reader, but it makes sense to people in the industry. To shed light on this trend I spoke with Ashley Neglia, who was the director of product marketing and ad innovation at The New York Times for three years. She said the role means “working in between the newsroom, product, and sales. My job is to work very closely with the newsroom as they come up with new ideas, and for me to determine what might be interesting to an advertiser. What might be sellable or sponsorable?” Neglia’s response captures the special position product teams hold within the organizational structure of a news publisher. Previously, publications were made up of two entities: the newsroom and the business side of the operation. Product marketing works in the middle.

When news organizations create new teams like product marketing, they are able to skirt the implication that news staff work directly with brands to craft commercial content—something that would damage the publication’s reputation and make its own brand identity less valuable. The product marketing team is responsible for the negotiation between publisher and advertiser. They shape the conversation with the newsroom and marketers, respectively.

If an editor wants to work on a culinary trends column, the product development team will consult various brands to see if a company wants to be associated with such content. For example, Vox sold Infiniti (the car company), a native advertising initiative that blended into Eater’s culinary coverage. It was called The Museum of Food and Drink, and featured a series of articles outlining the latest trends in the culinary world. The native advertising campaign was labeled “Presented by Infiniti” (see Figure 1). It takes further digging to see the disclosure text that said news staff had no hand in creating the content (see Figure 2).[13]

Figure 1: Red Bull mentions its energy drink sparingly in its branded videos, instead featuring people who take on athletic or adventurous tasks. They post these videos to more than 8 million subscribers on YouTube, under their channel, which is clearly labeled “Red Bull.”

Figure 2: The native ad above was posted by an Instagram influencer, Melissa Frusco, who has more than 34,000 followers. The post is labeled an ad for Neiman Marcus.

Every interview conducted as part of this report circled one question: is native advertising ethical if it looks like real news? Most subjects said they believe they craft ethical native advertisements. Almost everyone who defended the practice evoked the church and state axiom. They said their publisher understood the importance of keeping the newsroom (church) separate from the advertising department (state). However, a few people said they understood that native ads do present a threat to traditional newsroom values. Four people said sometimes publishers get it wrong. Pete Tosiello worked in The Atlantic’s branded content studio and said the publisher did work on ads that had no place in journalism. Tosiello cited the native ad The Atlantic ran for the Church of Scientology in 2013. The ad outlined the growth of the Church and came out right before New Yorker writer Lawrence Wright’s book Going Clear, an expose on the Church’s hidden practices. It was created to offset the negative press generated from Wright’s book. The publisher removed the native ad, and apologized for their poor judgment. Tosiello said that after stumbling over a few native ads they became more discerning and probably wouldn’t make the same mistake today. When he discussed the practice he said it was essentially “Calling in world-class publications to effectively write press releases.”[14]

Many people said they didn’t feel comfortable talking on the record about certain partnerships or how some deals are negotiated between the newsroom and marketers. Five different sales people from legacy news publishers said there were always avenues for advertisers to collaborate with the newsroom. They each discussed going on sales meetings with a popular journalist. If the wall between the newsroom and advertisers is as sturdy as most interviewees proclaimed, I was curious to see how they justified bringing journalists on sales calls.

Most interviewees said there is no conflict of interest because they align branded content with projects, columns, or articles their respective newsroom is already in the process of producing. A trend did emerge, people who adamantly defended the practice were employed by a publisher during the time I interviewed them. However, those who shared their skepticism about the trend had left the industry. Tracy Doyle worked at The New York Times, where she was creative director, for over two years. She put it in perspective—when asked how she felt about the ethics of native advertising, she simply said:

This is not in line with the campaign they are putting out that talks about the truth when they will turn around with another hand and take money from an advertiser to run an ad about fracking not being bad. We know that this is not the truth. This is what happens when you have glorified salespeople running The New York Times — their take-money-from-anyone mindset ultimately jeopardizes the journalistic integrity of the newspaper.[15]

Doyle was referencing a native ad the legacy publisher created for Chevron. Beneath the header, “Innovation Unlocks Untapped Energy” readers saw the text, “more effective extraction techniques, such as hydraulic fracturing — unlocked vast, previously untappable reserves. In turn, ample supply has reduced natural gas prices to historic lows.”

Despite the obvious problems with writing native ads that oppose the information coming out of a publisher’s newsroom most interviewees defended the practice. Almost everyone I spoke to said native advertising is a valuable and necessary revenue stream for publishers. The dire economic state of the publishing industry seemed to offset any ethical concerns over the potential native ads have to confuse newsreaders. It is worth noting that many people who work in branded content studios used to be journalists. They are familiar with the values, rigor, and dedication reporters exercise when pursuing a story. Despite this desire to keep journalistic ethics intact while crafting native ads, the pressure to secure advertising revenue is substantial.

Denise Burrell-Stinson used to be a freelance journalist and is currently the head of storytelling at The Washington Post’s branded content studio. In this role, she creates media for advertisers. This involves pitching clients’ stories in the form of articles, videos, and podcasts. Burrell-Stinson actively works with clients, creates branded content, and sells story ideas by leveraging her past experience working as a journalist. She reminds brands that she has been trained to tell meaningful stories people care about for years. Burrell-Stinson has been at The Post over a year and has seen the company’s culture intensify. “The mandate here is to up your game all the time . . . push the envelope, make it bigger,” she said. Nearly everyone I spoke with mentioned the push to make work that has “never been done before.”

Clients routinely ask Burrell-Stinson, Neglia, and Harvey to show them advertising opportunities that have never been offered to anyone else. This isn’t a request; it’s an ultimatum. Clients can go to an advertising agency if they simply want a thirty-second ad or Instagram post. Marketers work with publishers because they want to be associated with the trust people place in organizations like The Washington Post. They want commercials that don’t strike readers as advertising at all, something that has never been done before.

Why Should We Pay Attention to Native Advertising?

Over 30 interviews, a common theme emerged: Clients have all the bargaining power. Marketers have well-established relationships with their ad agency of record and view news publishers as one piece of their larger promotional plan that can easily be jettisoned for another line-item on the budget. A client’s agency of record is in the unique position to advise a brand on where they should spend their money— which platforms are worth valuable distribution dollars. This environment means news organizations have to build a relationship with advertisers, one that enables them to be more than a distribution line-item. The dynamic encourages product marketing teams to work directly with the newsroom to create original opportunities for brands to sponsor. When a product team can give a client an opportunity to embed their brand in or near news coverage, then the publisher becomes more than a simple distribution platform. Reporters, editors, and news workers will need to be equipped to address these new requests coming out of the business side of a newspaper as long as native advertising remains en vogue.

The economic pressure on newsrooms across the country has made branded content studios compete against one another for revenue. When publishers are asked to “push the envelope” of what is possible, the results benefits clients, not readers. Clients have consistently approached the people I interviewed and informed them that another publisher offered them a partnership closely aligned with one journalist’s column, or a new type of sponsorship altogether. Then they asked the person I interviewed whether they can match the offer or enhance it in some way. For example, ad labels vary and clients can often push publishers to create a label that is vague, or none at all, if they show that another publisher is willing to offer the same vague or nonexistent label. Branded content that can be difficult to spot exists in events a publisher hosts, in the podcasts it produces, in a series of columns—indeed, it is present in every medium a publisher is using.

Every publisher in this study uses a data analytics company like Chartbeat or Parse.ly to measure how readers engage with their coverage; this data is used by both the newsroom and branded content studios. Studios are able to share this proprietary data with advertisers when they are trying to sell branded content around a specific topic like travel. Product managers often create partnerships around topics readers are most likely to engage with, determined using engagement data from readers’ browsing patterns. Branded content producers interviewed for this study overwhelmingly said they wanted to make native ads that sound and look like the work produced by their respective newsroom—branded content that is “Times-ian” or sounds like an explainer article Vox’s newsroom would write.

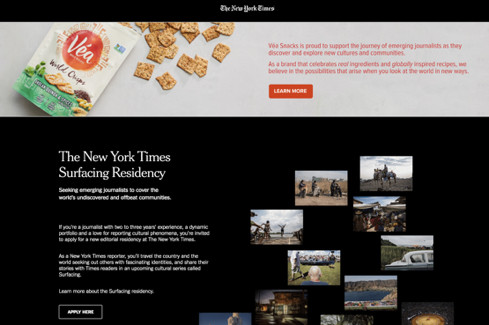

In the winter of 2017, The New York Times launched a native advertising initiative. The ad series was labeled, “An editorial residency with the support of Véa, a snack company owned by Mondelez.”[16] The text describing the residency itself was vague and wasn’t written in the form of a normal job description: the Times had created a standalone website asking journalists with two to three years of experience to apply to a new editorial residency. The website hosting the application portal said, “As a New York Times reporter, you’ll travel the country and the world seeking out others with fascinating identities, and share their stories with Times readers in an upcoming cultural series called Surfacing.”[17] At the bottom and top of this landing page the logo of the snack company appeared with the text “Supported by Véa” (see Figures 3 and 4).[18]

Figure 3: The Véa-New York Times partnership as it appeared on desktop browsers.

Figure 4: The Véa-New York Times partnership press release.

This initiative, labeled as a residency, was actually Véa funding reporters to cover food, culture, and travel for New York Times readers.

As Jason Levine, vice president of marketing for Mondelez International, said in a press release for the native ad,

We are proud to help The New York Times empower a new era of journalists to uncover new experiences, seek out others with fascinating identities and share those authentic stories in real-time—an endeavor that truly resonates with and engages Véa fans.[19]

Meanwhile, the Times newsroom was responsible for recruiting and training Véa residents to explore the world and create food, culture, and travel content within its Travel section, all led by the Times travel editor Monica Drake. In the same release, Sebastian Tomich, senior vice president of advertising and innovation at The New York Times, said:

We’re excited to work with the Véa brand because their spirit of exploration and presence is very much aligned with the kinds of stories that curious Times readers come to us for day after day. We’re looking for the next generation of passionate and thoughtful creators who are pushing the boundaries on how to tell stories and how to tap into what’s at the core of culture right now.[20]

The Véa residency blurs the boundary between newsroom content and advertising messaging by centrally placing Véa’s brand in the context of a real reporting job description. Further, there was no clear label identifying the content as an advertisement. It’s important to note the product marketing team that helps craft these deals between advertisers and the newsroom report directly to Tomich. But these product teams are only one part of the story. There are also former journalists who craft commercial messages for advertisers.

Native Advertising and Journalism

The rise of native advertising leads to other questions about the state of journalism that news organizations haven’t been addressed fully:

- Should reporters share what they are working on with product marketing teams? When the newsroom works with product teams—whether simply by consulting on journalistic standards or by partnering more deeply— its knowledge and expertise get commodified and shared with advertisers in an effort to create branded content.

- Does native advertising affect how real news stories are crafted and delivered?

- Does native advertising challenge the supposition of objectivity accorded to modern reporting?

- Does native advertising taint or otherwise undercut the relationship between publishers and the readers who trust them for independent coverage of companies that may buy advertising from them?

These questions pose new challenges for news workers. News organizations have never placed such a premium on the data they have about readers, or the targeting capabilities publishers can implement. Today, reporters are well aware that they need to keep readers on an article page. This allows publishers to tell advertisers they have a healthy audience of engaged readers, reachable through ad placements that look like news stories. Research has shown newsrooms know they have to keep readers on article pages and actively engaging with content; this knowledge can shape reporting decisions.[21] What is clear in this study is that journalists see that branded content generates revenue and thus secures the future of their publication and consequently their job. Pete Tosiello worked in The Atlantic’s branded content studio and said the need for ad revenue was visible on both the business and newsroom side of the publication. “There were pressures to band together. In some cases popular reporters came to sales meetings.”[22] They came to these meetings to try and help close ad deals. Reporters may not negotiate the price of a native ad, but they are certainly recognize the importance of these conversations.

Native Advertising & News Readers

In 2015, content marketing company Contently conducted an in-depth study that showed hundreds of people a combination of editorial and clearly labeled native ads. The company,which has a financial interest in ensuring that native advertising remains popular and profitable, found that “most consumers identified the native ad as an article. That includes native ads on The Wall Street Journal (80 percent identified it as an article), The New York Times (71 percent), BuzzFeed (71 percent), and Forbes (65 percent).”[23]

Advertisers invest in branded content and native advertising because they are said to capture the valuable attention of readers. People engage with native ads for a variety of reasons; they may find the content intriguing, or they may not realize it is a commercial message.

News publishers try to sell the status, reputation, and aura of their newsroom and the reporting skills of their investigative journalists to create a case for why advertisers should trust news publishers to craft commercial messages. The premise of native content studios is that they are able to use the same skills journalists utilize to tell compelling stories and engage readers.These studios employ former journalists, pay them well, and show marketers that ads crafted by news publishers will be executed with the same level of care as news stories.[24] Employees can also transfer between the newsroom and branded content studio of same publisher.[25] It’s important to note here that the majority of native ads don’t have bylines, making it easy for journalists at a publisher to write commercial content without readers knowing. This trend means former journalists are able to leverage their skill sets in advertising departments across major newspapers.[26] The question then becomes, what if it works? What if readers find native advertising to be just as compelling and persuasive as real news?

Brandon Keenen, senior director at BuzzFeed, answered this question:

Our branded content at times outperforms our editorial content. It really just depends on the content. We don’t see a massive drop-off on branded content, so it’s a great opportunity for brands to engage with the audience and a community in a way that there’s no lesser value in because it’s branded or promoted by. It’s really important to keep it authentic and to make sure that the content resonates with the audience regardless if there’s a brand or not.[27]

Audience development teams work directly with social media platforms like Facebook and Twitter to ensure people are reading native ads. Articles coming out of the newsroom have their own audience development teams that share the same skill set: optimizing headlines, imagery, and text. However, each real news story is not amplified to get a specific number of clicks. But branded content studios have promised clients a specific number of clicks and thus have a financial obligation to amplify commercial messages.

This can come at the cost of promoting editorial content, since both real news stories and native ads are competing for a reader’s attention. Yogini Patel was an ad optimization coordinator at BuzzFeed, where she was tasked with ensuring branded content performed well and attracted reader attention. When asked how she worked with the newsroom to promote branded content, she said reporters would share information about what people clicked on, the time of day posts should be put up, and so forth. She also said, “We were talking to them [the newsroom] before posting anything.”[28]

By consulting with the newsroom, Yogini knew when to post content and could make sure the newsroom was not covering similar stories. This check-in with the newsroom ensured her branded content stories would receive as many clicks as possible; they wouldn’t come out at the same time the newsroom was running a comparable story.

Some of the largest criticisms of native advertising are focused on disclosure and transparency. Regulators and publishers consider native ads ethical if they are labeled clearly. Upholding clear discourse standards is predicated on the assumption that if readers know they are reading commercial messages, because the ad is clearly labeled, then native advertising as a practice can’t be deceptive.

The Limitations of Current Regulation

In theory, the disclosure mandated by FTC regulation shields readers from being tricked or misled into reading commercial content and thinking it was produced by a journalist. However, complete transparency is not a proactively enforced legal standard, as evidenced by the fact that many publishers do not follow the FTC’s laws on native advertising.

MediaRadar is an advertising intelligence company that tracks where ads are placed and sells that information to ad agencies, brands, and media companies. In 2017, the company reviewed more than 12,000 pieces of native content across a variety of publisher websites and found that 40 percent of native advertisements ignore the FTC’s regulations.[29]

The company also found that nearly two out of five publishers creating native ads are not compliant with FTC’s guidelines.[30] There is a distinction here that is easy to miss: the study did not find that brands themselves are being deceptive. Rather, the publishers making the native advertisements are not following the FTC’s rules. These rules do not provide publishers with standard wording for disclosure, though. Publishers use different labels to mark native content, which can be confusing to readers. A single publisher,

The Atlantic uses a variety of labels: “Crafted by,” “Presented by,” and in one case simply “With.” In a branded content campaign for Nest, The Atlantic’s branded content studio worked with PSFK— a research company— to create a custom research report that stated the benefits of using Nest products. The report, “Home Debrief” simply said “PSFK with The Atlantic” (see Figure 5).

Figure 5: The Atlantic’s partnership with Nest, attributed here to researcher PSFK.

Minimizing disclosure up to, and potentially even beyond, the legal standard of transparency adds a fatal layer of confusion to a world of public information that already confounds a skeptical, digital-native readership. Sarah McGrew co-directs the Civic Online Reasoning project at Stanford University and conducted a study on native advertising that looked at how high school students respond to this form of commercial content. Researchers presented high school students with screenshots of two articles on global climate change. One screenshot was a traditional news story from a magazine’s science section. The other was a post sponsored by an oil company, which was labeled sponsored content and prominently displayed the company’s logo. The students were asked to identify which source was more reliable. Almost 70 percent said the sponsored content screenshot, which contained a chart with data, was more reliable.[31]

The findings indicated that students were often fooled by the eye-catching pie chart in the oil company’s post, despite the fact that there was no evidence that the chart represented reliable data.[32] One student said that the oil company’s article was more reliable because, “It’s easier to understand with the graph and seems more reliable because the chart shows facts right in front of you.”[33] Only 15 percent of students concluded that the news article was the more trustworthy source of the two screenshots.

If native advertising convinces readers that brand stories are factual, informative, and worth reading, then journalists have something to worry about. The novel problem native advertising presents may be what happens when people interpret ads as journalistic and trustworthy even when they are clearly labeled as sponsored content. McGrew’s research captures an essential part of this conversation: disclosure might not be the primary problem. Rather, the problem with native advertising is that it accomplishes exactly what it sets out to do—it looks as trustworthy and well-reported as a real news story. The BBC’s branded content studio explicitly says it is “the creative studio with newsroom values . . . embodying the BBC’s creative spark and rigorous editorial quality to help brands connect through beautifully crafted storytelling.”[34] Branded content studios are selling their ability to produce content that looks just as believable as real news stories. McGrew’s study proves that branded content studios are delivering on this promise to their clients. Producers of native content know they are in the business of copying whichever strategies and tactics the newsroom deploys to maintain reader trust.

Perhaps the most troubling aspect of this study is that when students were given a side-by-side comparison between a native ad and a real news story, they didn’t simply think the native ad was better, they thought it was more trustworthy because it had a compelling data visualization.

Advertisers pour money into making content that looks virtually identical to real news; social media experts then sit within branded content studios where they test each native advertising headline and potential image, all in an effort to make sure readers are clicking. Editorial departments have audience development teams as well, which test and optimize headlines, but the newsroom doesn’t need to hit a certain number of readers per article. News publishers also work to amplify news across social media platforms, but again they don’t have to meet specific click-through goals. Exposure aside, regulatory efforts may be focused on the wrong issues. The problem shouldn’t be limited to discussions that emphasize the importance of disclosure, labels, and media literacy.

When brands are armed with real-time newsroom data showing what people are engaging with, ads can be instantly updated and served. Regulation around native advertising should also require that publishers have readers open commercial content in an entirely new browser window, with a URL that has “advertiser content” in the name instead of “paid-post/nytimes.com,” for example.

Eye-catching content, created by storytelling experts and funded by a brand, may actually be taking readers away from reading the editorial content independent newsrooms create. When brands work with publishers to create branded content they are promised a specific number of clicks or engagement. Publishers then have to promote the branded content they’ve created on their website and on social media platforms to meet the promised number of clicks. Therefore, it is entirely possible that people will see a branded content story before they see a real news article because publishers are paying platforms to promote commercial messages, not newsroom articles.

Every time a deal is negotiated between an advertiser and a publisher’s branded content studio, a specific number of clicks or engagement metrics are promised to the client. Branded content studios have a contract to deliver clients with the pre-established engagement metrics. Newsroom reporters aren’t contractually obligated to hit a specified number of clicks on their articles; especially at legacy publications like The New York Times. However, branded content studios are contractually obligated to hit specified engagement metrics when working with marketers. If by working with publishers advertisers are winning out in securing reader attention through native ads, this has the potential to undermine an important mission of news organizations: maintaining an informed public.

Conclusion: What Should We Do?

The resounding theme in these interviews was the overwhelming desire people had to defend the native ads created inside a publishers’ branded content division. Nearly everyone said native ads provide value to readers or at least that is the goal of this type of marketing. Burrell-Stinson, of the Washington Post, said that there is a shared mission between the newsroom and branded content producers: “The content that does the best feels like good storytelling. People who come from real newsrooms… they bring the best talent and authority.” She went on to explain that hiring journalists enables branded content studios to show that they can produce work that is just as compelling as what comes out of newsrooms.

Her response seems to skirt the question many people have: is the wall between reporters and advertisers still sturdy? Burrell-Stinson’s response encapsulates what many other native advertising practitioners have said—that great stories can be told on either side of the wall. When asked about ethical considerations, people adamantly stated that the ultimate goal of branded content is similar to that of a newsroom—to produce compelling stories. Practitioners did not feel the line between newsroom and commercial content was being blurred; almost everyone thought there was no reason brands shouldn’t create content that is just as thoughtfully put together as their publication’s news copy. Lisa Harvey, Denise Burrell-Stinson, Ashley Neglia, each clearly stated that they work with clients whose mission and story is closely aligned with the publisher that employs them. It would be easy to think branded content producers are behaving recklessly, and some people who used to work in the industry agree. But current producers of branded content don’t seem to reject ethical concerns, they simply don’t think commercial content threatens the independence of the newsroom.

These assertions fly in the face of established research on audience behavior. The very thing that gives this form of marketing power is its capacity to blend, to camouflage itself in any given environment—the commercial’s ability to be native.

Publishers depend on advertising revenue to support news gathering and production. This economic truth is no longer new. Native advertising shares many similarities with print advertorials—ads that were made to look like editorial content and had a small label at the top of the page marking them “advertorials” or “sponsored content” or a “special advertising section.” As with their digital decendents, this label was easy to miss when readers flipped through magazines and saw yet another page that looked like a news column. But the way native digital advertising is being made is unprecedented.

A senior editor at Digiday wrote, “The difference between an advertorial and a native ad lies in the content. Publishers are building out creative services teams [The Atlantic has a staff of 15; BuzzFeed has nearly 20] to help brands create content that fits the voice of the outlet, whereas advertorials don’t necessarily match up”[35]

Advertorials aren’t written by news publishers; clients or their ad agency provides the news outlet with text, words, and images. Native ads are different because they are produced within the walls of a news publisher from start to finish. When the voice of an advertiser mimics the authoritative and trustworthy voice of journalists, it is clear that something new is happening. Research shows that readers consistently mistake native advertisements for news stories.[36] We’ve also seen that regulating the labeling of commercial content is difficult to enforce. While these findings may paint a dark future for news, they also present readers with a unique opportunity to demand more transparency from news outlets. If enough readers voice their concerns about branded content, news outlets will have to respond.[37] At the moment, many readers are confused by native ads because they don’t realize how prevalent they are and just how much they blend into the look and tone of news stories.[38] However, if more people become aware of the trend and its prevalence at trusted newspapers, they may be more willing to demand transparency in exchange for subscription dollars.

Acknowledgments

This report would not have been possible without the support of Emily Bell and the Tow Center. Thanks to Elizabeth Watkins for her keen understanding of the digital ad space and critical eye that greatly helped refine my own thinking. Thanks to Sam Thielman and Pete Brown for their patience, thoughtful comments, and razor-sharp edits.

Thank you to all of the people inside publishing and media who allowed me to interview them, their perspective added much-needed nuance to this report. Finally, I’d like to thank Professor Michael Schudson, Professor Andie Tucher, Professor Rodney Benson, and Professor Sam Freedman for their continuous support of my work on this topic.

Notes

[1] NYT Interview. Ava Sirrah. Phone interview. New York, April 25, 2017.

[2] Buzzfeed Interview. Ava Sirrah. Phone interview. New York, February 2, 2017.

[3] Tosiello Interview. Ava Sirrah. Phone interview. New York, July 21, 2019.

[4] Wu, Tim. The Attention Merchants from the Daily Newspaper to Social Media, How Our Time and Attention Is Harvested and Sold. London: Atlantic Books, 2016.

[5] Dunlap, David W. “1985 | Reaching an Earlier Million.” The New York Times, October 8, 2015.

https://www.nytimes.com/2015/10/08/insider/1985-reaching-an-earlier-million.html.

[6] Chaffey, Dave. “Average Display Advertising Clickthrough Rates.” Smart Insights, April 16, 2019.

https://www.smartinsights.com/internet-advertising/internet-advertising-analytics/display-advertising-clickthrough-rates/.

[7] McLellan, Michele. The Rise of Native Ads in Digital News Publications. Report. Entrepreneurial Journalism, Tow-Knight.

[8] O’Reilly, Lara. “Ad Blocker Usage Is up 30% – and a Popular Method Publishers Use to Thwart It Isn’t Working.” Business Insider. January 31, 2017. Accessed April 29, 2018.

https://www.businessinsider.com/pagefair-2017-ad-blocking-report-2017-1.

[9] Rittenhouse, Lindsay. “The New York Times Hires JWT N.Y. Chief Creative Officer Ben James for Its Branded Content Studio.” Adweek, March 29, 2019.

https://www.adweek.com/agencies/the-new-york-times-hires-jwt-chief-creative-officer-ben-james-for-its-branded-content-studio/.

[10] ATTN Interview. Ava Sirrah. Phone interview. New York, October 12, 2017.

[11] Benton, Joshua. “The Leaked New York Times Innovation Report Is One of the Key Documents of This Media Age.” Nieman Lab, May 14, 2014.

https://www.niemanlab.org/2014/05/the-leaked-new-york-times-innovation-report-is-one-of-the-key-documents-of-this-media-age/.

[12] Atlantic Interview. Ava Sirrah. Phone interview. New York, October 15, 2018.

[13] Melissa, Melissa. “@Theincogneatist.” Instagram, n.d.

https://www.instagram.com/theincogneatist/?hl=en.

[14] Tosiello Interview. Ava Sirrah. Phone interview. New York, July 21, 2019.

[15] Doyle Interview. Ava Sirrah. Phone interview. New York, July 26, 2018.

[16]“Stories That Influence The Influential.” T Brand Studio, n.d.

https://www.tbrandstudio.com/.

[17] “The New York Times Surfacing Residency.” The New York Times, n.d.

https://www.nytimes.com/marketing/surfacing/index.html.

[18] Redbull. “Red Bull.” YouTube. YouTube, n.d.

https://www.youtube.com/user/redbull.

[19] Véa Brand. “The Véa Brand Teams Up With The New York Times To Promote First-Of-Its-Kind Times Residency For Emerging Journalists.” PR Newswire, June 26, 2018.

https://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/the-vea-brand-teams-up-with-the-new-york-times-to-promote-first-of-its-kind-times-residency-for-emerging-journalists-300533623.html.

[20] Véa Brand. “The Véa Brand Teams Up With The New York Times To Promote First-Of-Its-Kind Times Residency For Emerging Journalists.” PR Newswire, June 26, 2018.

https://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/the-vea-brand-teams-up-with-the-new-york-times-to-promote-first-of-its-kind-times-residency-for-emerging-journalists-300533623.html.

[21] Christin, Angèle. “Counting Clicks: Quantification and Variation in Web Journalism in the United States and France.” American Journal of Sociology 123, no. 5 (2018).

https://doi.org/10.1086/696137.

[22] Tosiello Interview. Ava Sirrah. Phone interview. New York, July 21, 2019.

[23] Lazauskas, Joe. “The Problems Facing Native Advertising, in 5 Charts.” The Content Strategist. September 24, 2015. Accessed April 29, 2018.

https://contently.com/strategist/2015/09/16/the-problems-facing-native-advertising-in-5-charts/.

[24]Pompeo, Joe. “Going Native at the Times.” Politico, September 29, 2014.

https://www.politico.com/media/story/2014/09/going-native-at-the-times-003034.

[25] Silverman, Jacob. “The Rest Is Advertising: Jacob Silverman.” The Baffler, July 3, 2019.

[26] Hannay, Megan. “Local Journalism, Meet Branded Content: What the Decline in Print Means for Brands.” Marketing Land, August 17, 2016.

https://marketingland.com/local-journalism-meet-branded-content-decline-print-press-means-brands-187749.

[27] Andersen, Stine. “BuzzFeed on How to Make Native Advertising Go Viral.” Native Advertising Institute, July 17, 2017.

https://nativeadvertisinginstitute.com/blog/make-native-advertising-go-viral/.

[28] Buzzfeed Interview. Ava Sirrah. Phone interview. New York, February 2, 2017.

[29] Fletcher, Paul. “Report: Nearly 40% Of Publishers Ignore FTC’s Native Advertising Rules.” Forbes. March 20, 2017. Accessed April 29, 2018.

[30] Fletcher, Paul. “Report: Nearly 40% Of Publishers Ignore FTC’s Native Advertising Rules.” Forbes. Forbes Magazine, March 20, 2017.

https://www.forbes.com/sites/paulfletcher/2017/03/19/nearly-40-percent-of-publishers-ignore-ftcs-native-advertising-rules/2/#6f054881495b.

[31] McGrew, Sarah. “The Challenge That’s Bigger Than Fake News.” American Federation of Teachers, September 26, 2017.

https://www.aft.org/ae/fall2017/mcgrew_ortega_breakstone_wineburg.

[32] McGrew, Sarah. “The Challenge That’s Bigger Than Fake News.” American Federation of Teachers, September 26, 2017.

https://www.aft.org/ae/fall2017/mcgrew_ortega_breakstone_wineburg.

[33] McGrew, Sarah. “The Challenge That’s Bigger Than Fake News.” American Federation of Teachers, September 26, 2017.

https://www.aft.org/ae/fall2017/mcgrew_ortega_breakstone_wineburg.

[34] Storyworks”. 2019. Https://Www.Bbcglobalnews.Ltd/Solutions/Bbc-Storyworks/.

https://www.bbcglobalnews.ltd/solutions/bbc-storyworks/.

[35] Sternberg, Josh. “Native Ads or Advertorials?” Digiday, September 25, 2012.

https://digiday.com/media/native-ads-or-advertorials/.

[36] “Article or Ad? When It Comes to Native Advertising, No One Knows.” Contently, February 1, 2017.

https://contently.com/2015/09/08/article-or-ad-when-it-comes-to-native-no-one-knows/.

[37] Lawson, Linda. Truth in Publishing: the Newspaper Publicity Act as Government Regulation of the Press. Ann Arbor, MI: University Microfilms International, 1989.

[38] Amazeen, Michelle A, and Bartosz W Wojdynski. “The Effects of Disclosure Format on Native Advertising Recognition and Audience Perceptions of Legacy and Online News Publishers.” Journalism: Theory, Practice & Criticism, July 2018.

https://doi.org/10.1177/1464884918754829.

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.