To print or a read a PDF of this report, visit the Tow Center’s Gitbook page.

Tip Sheet

Audience metrics have become ubiquitous in news organizations, but there has been little empirical research on how the data is produced or how it affects newsroom culture and journalists’ daily work. The Tow Center sought to understand how the use of metrics changes reporters’ behavior and what this means for journalism. Thus, researcher Caitlin Petre conducted ethnographic analysis of the role of metrics in journalism, focusing on three case studies: Chartbeat, a dominant metrics vendor; Gawker Media, a newsroom intently focused on metrics; and The New York Times, a legacy news outlet where metrics are currently more peripheral. Petre offers the following key points based on her findings.

- Metrics exert a powerful influence over journalists’ emotions and morale. Metrics inspire a range of strong feelings in journalists, such as excitement, anxiety, self-doubt, triumph, competition, and demoralization. When devising internal policies for the use of metrics, newsroom managers should consider the potential effects of traffic data not only on editorial content, but also on editorial workers.

- Traffic-based rankings can drown out other forms of evaluation. It is not uncommon for journalists to become fixated on metrics that rank them or their stories, even if these are not the sole criteria by which they are evaluated. Once rankings have a prominent place on a newsroom wall or website, it can be difficult to limit their influence.

- News organizations can benefit from big-picture, strategic thinking about analytics. Most journalists are too busy with their daily assignments to think extensively or abstractly about the role of metrics in their organization, or which metrics best complement their journalistic goals. As a result, they tend to consult, interpret, and use metrics in an ad hoc way. But this data is simply too powerful to implement on the fly. Newsrooms should create opportunities—whether internally or by partnering with outside researchers—for reflective, deliberate thinking removed from daily production pressures about how best to use analytics.

- When a news organization is choosing an analytics service, it should consider the business model and the values of the vendor. We have a tendency to see numbers—and, by extension, analytics dashboards—as authoritative and dispassionate reflections of the empirical world. When selecting an analytics service, however, it’s important to remember that analytics companies have their own business imperatives. Newsroom managers should consider which analytics company’s values, branding strategy, and strategic objectives best align with their own goals.

- Not everything can—or should—be counted. Efforts to improve audience analytics and to measure the impact of news are important and worthwhile. But newsroom, analytics companies, funders, and media researchers might consider how some of journalism’s most compelling and indispensable traits, such as its social mission, are not easily measured. At a time when data analytics are increasingly valorized, we must take care not to equate what is quantifiable with what is valuable.

Executive Summary

In a 2010 New Yorker profile, founder and CEO of Gawker Media Nick Denton argued, “probably the biggest change in Internet media isn’t the immediacy of it, or the low costs, but the measurability.” 1

What does all this data mean for the production of news? In the earlier days of web analytics, editorial metrics had both enthusiastic proponents and impassioned detractors. Nowadays the prevailing view is that metrics aren’t, by definition, good or bad for journalism. Rather, the thinking goes, it all depends what is measured: Some metrics, like page views, incentivize the production of celebrity slide shows and other vapid content, while others, like time on a page, reward high-quality journalism. Still, there are some who doubt that even so-called “engagement metrics” can peacefully coexist with (let alone bolster) journalistic values.

This report’s premise is that it will be impossible to settle these debates until we understand how people and organizations are producing, interpreting, and using metrics. I conducted an ethnographic study of the role of metrics in contemporary news by examining three case studies: Chartbeat, Gawker Media, and The New York Times. Through a combination of observation and interviews with product managers, data scientists, reporters, bloggers, editors, and others, my intention was to unearth the assumptions and values that underlie audience measures, the effect of metrics on journalists’ daily work, and the ways in which metrics interact with organizational culture. Among the central discoveries:

- Analytics dashboards have important emotional dimensions that are too often overlooked. Metrics, and the larger “big data” phenomenon of which they are a part, are commonly described as a force of rationalization: that is, they allow people to make decisions based on dispassionate, objective information rather than unreliable intuition or judgment. While this portrayal is not incorrect, it is incomplete. The power and appeal of metrics are significantly grounded in the data’s ability to elicit particular feelings, such as excitement, disappointment, validation, and reassurance. Chartbeat knows that this emotional valence is a powerful part of the dashboard’s appeal, and the company includes features to engender emotions in users. For instance, the dashboard is designed to communicate deference to journalistic judgment, cushion the blow of low traffic, and provide opportunities for celebration in newsrooms.

- The impact of an analytics tool depends on the organization using it. It is often assumed that the very presence of an analytics tool will change how a newsroom operates in particular ways. However, the report finds that organizational context is highly influential in shaping if and how metrics influence the production of news. For instance, Gawker Media and The New York Times are both Chartbeat clients, but the tool manifests in vastly different ways in each setting. At Gawker, metrics were highly visible and influential. At The Times, they were neither, and seemed—to the extent they were used at all—primarily to corroborate decisions editors had already made. This suggests that it is impossible to know how analytics are affecting journalism without examining how they are used in particular newsrooms.

- For writers, a metrics-driven culture can be simultaneously a source of stress and reassurance. It is also surprisingly compatible with a perception of editorial freedom. While writers at Gawker Media found traffic pressures stressful, many were far more psychologically affected by online vitriol in comments and on social media. In a climate of online hostility or even harassment, writers sometimes turned to metrics as a reassuring reminder of their professional competence. Interestingly, writers and editors generally did not perceive the company’s traffic-based evaluation systems as an impediment to their editorial autonomy. This suggests that journalists at online-only media companies like Gawker Media may have different notions of editorial freedom and constraint than their legacy media counterparts.

The report calls for more research on analytics in a number of areas. More information is needed about readers’ responses to metrics. Are they aware that their behavior on news sites is being tracked to the extent that it is? If so, how (if at all) does this affect their behavior? The report also advocates for more studies using systematic content analysis to determine if and how metrics are influencing news content. Finally, I suggest further ethnographic research on the growing movement to create so-called “impact metrics.”

The report also makes three recommendations to news organizations. First, news organizations should prioritize strategic thinking on analytics-related issues (i.e., the appropriate role of metrics in the organization and the ways in which data interacts with the organization’s journalistic goals). Engagement with these big-picture questions should be insulated from daily traffic and reporting pressures but otherwise can take various forms; for instance, newsrooms that are unable to spare the resources for an in-house analytics strategist may benefit from partnerships with outside researchers. Second, when choosing an analytics service, newsroom managers should look beyond the tools and consider which company’s strategic objectives, business imperatives, and values best complement those of their newsroom. Finally, though efforts to develop better metrics are necessary and worthwhile, newsrooms and analytics companies should be attentive to the limitations of metrics. As organizational priorities and evaluation systems are increasingly built on metrics, there is danger in conflating what is quantitatively measurable with what is valuable.

Introduction

On August 23, 2013, the satirical news site The Onion published an op-ed purporting to be written by CNN digital editor Meredith Artley, titled “Let Me Explain Why Miley Cyrus’ VMA Performance Was Our Top Story This Morning.” The answer, the piece explained matter-of-factly, was “pretty simple.”

It was an attempt to get you to click on CNN.com so that we could drive up our web traffic, which in turn would allow us to increase our advertising revenue. There was nothing, and I mean nothing, about that story that related to the important news of the day, the chronicling of significant human events, or the idea that journalism itself can be a force for positive change in the world …But boy oh boy did it get us some web traffic.2

The piece went on to mention specific metrics like page views and bounce rates as factors that motivated CNN to give the Cyrus story prominent home page placement.

Of course, Artley did not actually write the story, but it hit a nerve in media circles nonetheless—especially since a story on Cyrus’s infamous performance at the MTV Video Music Awards had occupied the top spot on CNN.com and, as the real Meredith Artley later confirmed, did bring in the highest traffic of any story on the site that day.3

Media companies have always made efforts to collect data on their audiences’ demographics and behavior. But the tracking capabilities of the Internet, as well as the ability to store and parse massive amounts of data, mean that audience metrics have grown far more sophisticated in recent years. In addition to the aforementioned page views and bounce rates, analytics tools track variables like visitors’ return rates, referral sites, scroll depths, and time spent on a page. Much of this data is delivered to news organizations in real time.i

The widespread availability of audience data has prompted fierce debates in the journalism field. The Onion op-ed succinctly encapsulates one common position in this conflict, which is that metrics—or, more specifically, the desperate quest for revenue they represent—are causing journalists to abdicate their highest duties: to inform their audiences about the most important public issues of the day and to hold the powerful accountable. The more attention journalists pay to audience clicks, views, and shares, the more Miley Cyrus slide shows will beat out stories on important, difficult subjects like Syria or climate change. Proponents of an opposing view argue that the increased prominence of metrics in newsrooms is a powerful force of democratization in the media, offering a welcome end to the days when editors dictated which world events were important enough to be newsworthy. Differing views on metrics have manifested in a range of organizational policies for distributing and using the data: Many news sites make metrics widely available to editorial staff; some, such as Gawker Media and The Oregonian, have even paid writers partly based on traffic. Still, a (smaller) number of news sites, including The New York Times and Vox Media’s The Verge, actively limit reporters’ access to metrics.4

It’s not surprising that metrics have become a hot-button issue in journalism. Their presence invites a number of ever-present tensions in commercial news media to come crashing into the foreground. Among them: What is the fundamental mission of journalism, and how can news organizations know when they achieve that mission? How can media companies reconcile their profit imperative with their civic one? To the extent that the distinction between journalist and audience is still meaningful, what kind of relationship should journalists have with their readers?

In the midst of these normative questions, collective anxiety, and tech-evangelist hype, there must be more empirical research into the role that audience metrics actually play in the field of journalism.ii

This report aims to help fill these gaps. I undertook an ethnographic study of three companies—Chartbeat, the prominent web analytics startup, and two of the media organizations that use its tools, Gawker Mediaiii and The New York Times. I conducted interviews with staff members at these companies and observed meetings and interactions when possible.iv

Ethnographic research is, almost by definition, slow; it takes time to get to know how a workplace operates and establish an open and trusting rapport with subjects. The digital media field, which continues to change at a dizzying speed, poses particular challenges for this kind of slower-paced research. As I discuss in the conclusion, the three companies I studied have changed in terms of personnel and, in the case of Gawker and The Times, organizational structure since I concluded my research; they undoubtedly will continue to do so. Even so, this research is intended as more than a snapshot of these companies’ orientation toward metrics at a particular point in time. The ever-changing nature of the digital media field presents a challenge, but also a valuable exercise: It forces researchers to zoom out from particular details (the newest metric, the latest newsroom shake-up) and identify the bigger analytic themes that characterize the creation, interpretation, and use of news metrics. That is, above all, what this report aims to accomplish.

In conducting this research, I was interested in three big questions. First, how are metrics produced? At a time in which “let the data speak” is a common refrain in popular media, and judgments made on the basis of “number crunching” are widely considered more objective and reliable than those made using other methods, it is easy to forget that numbers are socially produced—that is, they are made by particular groups in particular contexts. There is substantial value in studying what sociologists Wendy Espeland and Mitchell Stevens call “the work of quantification.”5

In the case of metrics, researchers know quite a lot about the interests and principles of the journalists using analytics tools, but not much about the programmers, data scientists, designers, product leads, marketers, and salespeople who make and sell these tools. How do they decide which aspects of audience behavior should be measured and how to measure them? What ideas—about both those whose behavior they are measuring (news consumers) and those who will be using their tool (journalists)—are embedded in these decisions? How do analytics firms communicate the value of metrics to news organizations?

My second big question: how are metrics interpreted? Despite their opposing stances, arguments that metrics are good or bad for journalism have one thing in common: They tend to assume that the meaning of metrics is clear and straightforward. But a number on its own does not mean anything without a conceptual framework with which to interpret it. Who makes sense of metrics, and how do they do it?

Finally, I wanted to know how metrics are used in news work. Does data inform the way newsrooms assign, write, and promote stories? In which ways, if any, is data a factor in personnel decisions such as raises, promotions, and layoffs? Does data play more of a role in daily work or long-term strategy? And how do answers to these questions differ across organizational contexts?

As the report ventures answers to these questions, it sidesteps a more familiar (though, I would argue, less fruitful) one: do metrics represent a healing salve for the troubled field of journalism, or a poison that will irrevocably contaminate it? There is little point in debating whether or not metrics have a place in newsrooms. They are here, and they don’t seem to be going anywhere anytime soon. At the same time, we must not unthinkingly adopt a technologically determinist view, in which the very existence of metrics will inevitably cause certain norms, practices, and structures to emerge. What metrics are doing to—and in—newsrooms is an empirical question, not a foregone conclusion, and it is the one this report aims to address.

Case Studies and Methods

By looking closely at one analytics company and two media organizations that use its tool, this research is able to follow both how an analytics dashboard moves from the company that produces it to those that use it, and also how very different types of editorial groups integrate the same tool into their work.

Chartbeat is an important and ideal analytics company to study for several reasons. It has tremendous reach—its clients include 80 percent of the most-trafficked publishers in the United States, as well as media outlets in 35 other countries—yet is small enough that it is possible for an ethnographer to get a feel for the company as a whole. It was also one of the first analytics companies to make a dashboard specifically designed for use by journalists, rather than by advertising sales departments. During my time at Chartbeat, the company was building, marketing, and launching a brand new version of Chartbeat Publishing, its flagship editorial product; I was able to witness much of this process take place. From August 2013-January 2014, I spent time as a “fly on the wall” in Chartbeat’s offices, observing internal meetings, user experience research, client trainings, and the rhythms of daily office life. I also conducted 22 interviews and in-depth conversations with 16 employeesv

Gawker Media is a highly popular and visible network of blogs that covers topics ranging from gaming to sports to women’s issues. Gawker is widely known as a metrics-driven organization. In the early days of the company, owner Nick Denton developed a reputation for paying writers partly based on the page views their posts generated. The company also devised the Big Board (subsequently built by Chartbeat), a constantly updating screen displaying the top stories by traffic across all Gawker Media sites. During the time of my fieldwork, Gawker gave bonuses based on its sites’ unique visitor counts and had started publicly ranking individual writers by traffic. Gawker is a longtime client of Chartbeat and the two companies have a close relationship; while most of Chartbeat’s clients require that their data be kept confidential, Gawker allows Chartbeat to make its data public for training and other purposes. I conducted 30 interviews with writers and editors from six of Gawker’s eight core titles, as well as with a small number of editorial and business development executives. From February-July 2014, I also spent a total of five days observing the online group chats (conducted on the collaboration software Campfire) of two of the company’s core sites and attended occasional staff meetings. In addition, I analyzed the company’s internal memos (some of which staffers provided to me, others of which were leaked online).

If Gawker is known for being metrics-driven in all decision-making, The New York Times, at least at first glance, seems to have the opposite relationship to metrics. For years, representatives of The Times newsroom were publicly dismissive, even scornful, of the idea of using metrics to inform editorial processes. In the face of the paper’s ongoing financial troubles6 The Times’s culture around metrics may be changing. Though The Times is a longtime Chartbeat client, it only recently upgraded from the most basic iteration of the dashboard to the more sophisticated tool Gawker and most other large newsrooms employ. The Times’s complex and fraught relationship to analytics makes the organization an excellent case study through which to examine the interactions between metrics and legacy media practices and values. Between 2011 and 2015, I conducted 23 semi-structured interviews with 20 reporters, columnists, editors, bloggers, and analysts at The Times.

A Note on Access

Ethnographic observation and in-depth interviews provide valuable insight into how companies operate. However, it can be difficult to obtain access to corporate environments, and compromises are sometimes necessary to make such research possible. I was given access to Chartbeat on two conditions: first, that I would not share clients’ names or data; second, that I would allow the company to review all direct quotes and transcribed anecdotes from my time at the office. Of the 29 quotes and field-note excerpts I offered for review, Chartbeat left 24 unaltered, removed two altogether, and removed a single line or phrase from three. None of these edits substantially changed the presentation of my findings, and the company did not have advance access to any of my analysis or interpretation of the data. Gawker did not put any such limits on my access: everything I observed or heard in an interview was fair game for publication, except in the rare instances when interview subjects requested that something be off the record. At The Times, I arranged interviews with individual staffers but was not able to conduct observation in the newsroom. I guaranteed anonymity to individuals at all three research sites, so real names and identifying details have been omitted.

Chartbeat and the Making of Web Analytics

“It’s not the identity of the number [that matters]. It’s the feeling that the number produces …That’s the thing that’s important.”

-– Chartbeat employee

Data about audiences has long been a source of distrust—or, at least, indifference—for journalists. Journalism scholars who conducted fieldwork in newsrooms during the pre-Internet era found that print journalists took little interest in audience surveys, circulation data, or even more direct forms of feedback like letters from readers. Rather than write with a statistically informed picture of their audience in mind, instead they often relied on archetypes of a typical audience member—usually a family member—when considering the relevance of a particular story to readership. They also greatly valued the opinions of their colleagues and bosses, trusting them far more than the general public to determine whether a story qualified as good journalism.7

With the advent and spread of the Internet, two things changed. First, the data got much more sophisticated—meaning, it became far more detailed and specific and was available much more quickly. Second, changing structural conditions meant that newsrooms could no longer afford to ignore metrics. As content became more abundant and previously reliable sources of advertising revenue dried up, news organizations faced intensifying financial pressures. One way to win the fierce competition for dwindling ad dollars was to enlarge a publication’s audience, and metrics developed a reputation as a crucial tool for doing just that.

Still, the idea of using metrics to inform editorial decision-making was (and sometimes still is) met with derision, anxiety, and outright hostility by many journalists. In March 2014, the late Times media columnist David Carr warned, “Risks Abound as Reporters Play in Traffic.”8 The American Journalism Review asked, “Is Chasing Viral Traffic Hurting Journalism?”9 Even outlets that have a reputation for being extremely metrics-driven have voiced concerns. A BuzzFeed headline read, “Infinite Feedback Will Make Us Crazy”10; a Daily Beast piece on the “anti-clickbait movement” was entitled “Saving Us from Ourselves.”11

In this climate, a company determined to get metrics into a wide array of newsrooms had its work cut out for it. But by many measures, Chartbeat has succeeded at doing just that. As CEO Tony Haile often points out, the company works with 80 percent of the highest-trafficked publishers in the United States, as well as newsrooms in 35 other countries. This makes Chartbeat an intriguing research site for examining the production of analytics. How does Chartbeat decide what to count and how to present data? And just as important, how does Chartbeat market and sell its product to newsrooms?

The answers I uncovered during my research add complexity to the way we typically think about what metrics are and the function they serve within news organizations. In both popular and academic discourse, there is a widespread tendency to think of metrics as instruments of rationalization—as tools that systematically and scientifically measure the performance of news content and convey that information to journalists so that they can draw more traffic to their sites. Chartbeat often portrays its mission this way: the company’s website boasts that its dashboard allows clients to “see what interests visitors and adapt your site instantly,” “equip your team with decision-driving data,” and “know what content sparks and holds readers’ attention.” The client testimonials on Chartbeat’s site also employ dry, technical language. Here is Gawker’s: “By providing key information in real time, we have a more precise understanding of the traffic we must support as we add features to our next-generation live blog platform.” The prevailing message is that the dashboard exists to communicate rational, dispassionate data, upon which journalists can then act.

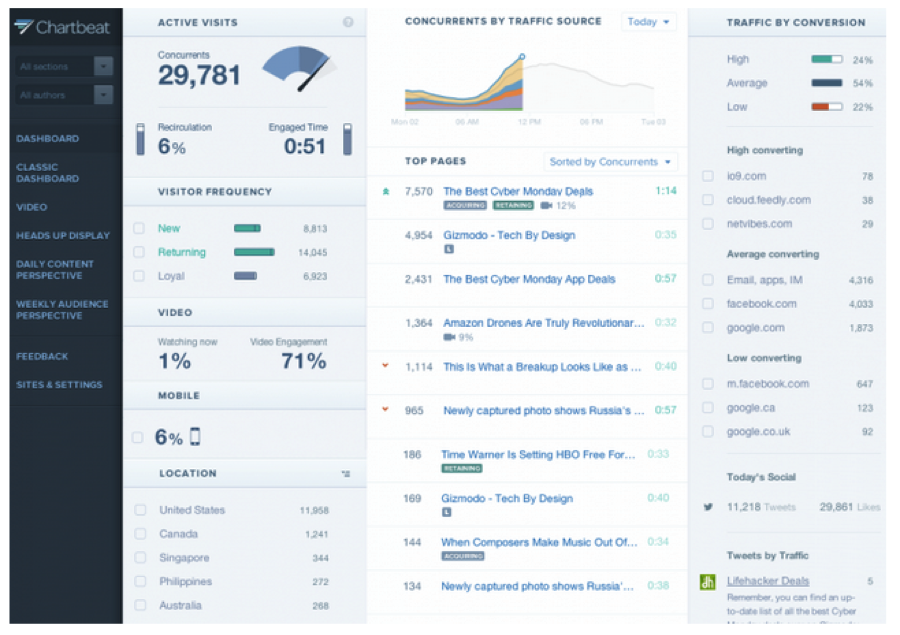

And indeed, Chartbeat’s analytics tool is designed to communicate data. The dashboard’s original distinguishing feature was its real-time information about visitors’ behavior (the name Chartbeat is a play on heartbeat, evoking this immediacy). The current publishing dashboard (Fig. 1) is packed with data about readers’ behavior. In a quick glance, one can see how many visitors are on the site (and on each particular page) at a given moment; the average amount of time they have been there; which Internet sites referred them; how often they visit; where in the world they are located; what percentage of them is looking at the site on mobile phones; and much more.

But a closer look at the dashboard, coupled with hours of observation and interviews with the people who dreamt up, built, and marketed it, reveals that providing rigorous data is only a part—and at times not even the most important part—of what the dashboard is designed to do. For Chartbeat to succeed, its product must appeal to the journalists whom are its intended audience. To accomplish that, the dashboard must do much more than merely communicate data. It must demonstrate deference for traditional journalistic values and judgment; it must be compelling; it must soften the blow of bad news; and finally, it must facilitate optimism and the celebration of good news. None of these things fall under our conventional understanding of what an analytics tool is and does, yet Chartbeat expends considerable energy and effort on them. Some of these aims can be accomplished within the actual dashboard; others, like demonstrating respect for traditional journalistic judgment, are accomplished both within the dashboard itself and in Chartbeat staff’s interactions with clients.

Communicating Deference to Journalistic Judgment

One of the most popular and widespread suppositions about big data is that the existence of new sources of data and new ways to process them will obviate the need for expert intuition and judgment, which has, the narrative goes, repeatedly proven itself to be unreliable. In a typical example, Economist editor Kenneth Cukier and Oxford professor Viktor Mayer-Schönberger wrote, “the biggest impact of big data will be that data-driven decisions are poised to augment or overrule human judgment.”12

In journalism’s more traditional corners, there is a fear that metrics will do more overruling than augmenting. One of the challenges for Chartbeat staff, then, is to present itself and the company’s products in a way that will assuage these worries and earn journalists’ trust. The company does this in two ways. First, staff members rhetorically defer to editors’ judgment—both in verbal interactions with clients and within marketing materials. In a client meeting I observed, a Chartbeat employee suggested the client look at data about its most valuable traffic source and added, “you already know it intrinsically, but the data confirms it.” (Of course, Chartbeat also has to avoid going too far with this type of message, lest the dashboard be considered unnecessary.)

The second way in which Chartbeat works to communicate deference and build trust is with the metrics themselves. The new Chartbeat Publishing dashboard prominently features two metrics in the top left-hand corner: engaged time, which is an average measure of how long people spend engaged with a site’s content, and recirculation, which is the percentage of people who visit at least one additional page on a site after the one at which they arrive. Just below these figures is a section on visitor frequency, which divides readers into three categories—new, returning, and loyal—based on how often they visit a site. In explaining the impetus for these particular metrics, Chartbeat employees and marketing materials position them against page views and other metrics that have a reputation for incentivizing the production of clickbait. By contrast, the company argues, Chartbeat’s metrics are designed to reward “high-quality content,” meaning the kinds of rigorous, thoughtful reporting and writing that are central to journalists’ professional identity. In a meeting I observed in which the Chartbeat team prepared for the product launch, the alignment between Chartbeat Publishing’s metrics and traditional journalistic values was a central selling point. As one employee put it, “this is the core of what we’re trying to do—reframe an audience from chasing meaningless metrics and starting out fresh every morning, to building a loyal and returning audience that [the client] can monetize in a variety of ways.”

Just as noteworthy as which features Chartbeat Publishing includes are the ones it leaves out. The dashboard doesn’t make recommendations about what kind of content to produce or where to place content on a page. This omission is not due to technological limitations or because such a feature would be ineffective at growing clients’ traffic; rather, it is a conscious attempt to avoid alienating journalists. When asked about Chartbeat’s strategy, a member of the development team explained:

We had a competitor who made a tool that made suggestions to editors …And it was like, “put this here, promote this story.” And editors were like, “I’m not using this damn thing …You’re telling me to put stuff in the lead spot I would never put there.” So we said, “listen, we’re not taking away your job; we’re enhancing your ability to make those decisions.”

Indeed, an anecdote about a Chartbeat competitor that exemplified this dynamic was invoked so frequently in internal meetings and interviews that I began to consider it part of the company folklore. At the Guardian Changing Media Summit in 2013, the digital editor of the British tabloid The Sun served on a panel with the founder and CEO of Visual Revenue, a predictive analytics company that provides algorithmic recommendations to news organizations about story placement and assignment. In speaking about his experiences using the product, Derek Brown, The Sun editor, said:

It’s a really valuable tool, but the one thing I’ve always said to Dennis [founder and CEO of Visual Revenue] …is that you kind of have to ignore it sometimes. Great example, last week: New Pope [was elected, and] Visual Revenue is telling us, screaming at us, “nobody is interested in this story! They’re far more interested in the Katy Perry story. Put that above the Pope. Put the Pope way down at the bottom of your home page. Nobody really wants to read it on your website.” And of course, at that point—and there’s lots of examples of that every day of the week—the human being has to intervene and say, “okay, they may be more interested in Katy Perry in a bikini today. However, the Pope is a far more important story.”13

That an editor at The Sun, a tabloid newspaper, so frequently found Visual Revenue’s recommendations inappropriate is indicative of the fraught relationship that news organizations of all stripes can have with analytics companies. At Chartbeat, “Katy Perry versus the Pope” (as the story was sometimes referred to during meetings) was a powerful symbol. This was in part because, as one staff member put it, “we don’t feel that’s how data should be used.” But it also served as a cautionary tale of the kind of overstepping that could damage an analytics company’s credibility with news organizations. The story became a vivid reminder of the delicate balance Chartbeat had to strike with clients. The company needs to show that data has something to contribute to decision-making without stepping on editorial toes.

The Candy and Vegetables of Metrics

With metrics like recirculation, visitor frequency, and engaged time, Chartbeat demonstrates its allegiance to journalistic values and gains journalists’ trust. However, none of these is the metric that many users find most compelling, nor for which the company is most famous. That would be “concurrent visitors,” and more specifically, the speedometer-like dial that shows how many people are on a site on a second-by-second basis. The dial and accompanying number’s constant movement give it a mesmerizing quality, leading users to call it “sanity-ruining,”14 “addictive,” and “the crack cocaine of web data.”15

CP: From my conversations with editors about this tool, they always say it’s addictive. Do you think it [is because the Chartbeat dashboard] sort of speaks to an editorial mindset? Do you think that the engaged-time thing is the reason why editors have taken to it?

I wish I could say yes, but no …I think the reason they find it addictive is—one is just performance. It’s such a fucking tough industry that you lose sleep, man. Like being a journalist is the hardest job in the world. It’s so stressful that you are constantly worrying about whether you’re getting enough traffic or not. So your eyes are glued to Chartbeat because your life depends on it. So I don’t have any real illusions about what got us in the door. That’s why they’re addicted. Now, we’re trying to be much, much more than that, obviously. And we all need to be a bit more honest about our actual value in some of these organizations right now, because there’s nothing more than that to some people.

Indeed, Chartbeat employees themselves were not immune to the dial’s seductive properties. As one staffer who sometimes writes for the company’s blog explained:

The whole real-time thing, like to me that’s the whole thing that makes it work as a product. You know, I write blog posts and I watch it. Those are the moments when you realize why it’s a successful product, because I watch it, and nobody reads my stuff, right? …If you look at it, you’re like, “there are three people reading this.” …And then somebody else comes in and you’re like, “oh, shit, there’s a fourth! Who’s that guy?!” And that’s the magic.

As the next section will demonstrate, my findings at Gawker confirmed that many writers and editors largely ignore those Chartbeat metrics designed to reward high-quality content in favor of the concurrents dial, which is the closest thing Chartbeat has to more typical metrics like page views and uniques. There is a disjuncture, then, between the metrics on which Chartbeat builds its reputation as an analytics company that supports serious journalism and the metrics that are actually most popular and alluring to many users. Ironically, Chartbeat finds itself in a situation similar to many of its publisher-clients, who are torn between producing “vegetable” content (nourishing but relatively unpopular) and “candy” content (empty but fun and, yes, addictive). In this vein, Chartbeat has vegetable metrics, such as engaged time and visitor frequency, which contribute to its prestige and to clients’ sense that Chartbeat “gets it.” But the dashboard also has candy metrics, like the concurrents dial, which give the dashboard its addictive properties.

Sheltering Clients from Bad News and Providing Opportunities to Celebrate Good News

As Chartbeat and other analytics tools become more common and influential in newsrooms, journalists’ sense of dignity, pride, and self-worth are increasingly tied up in their traffic numbers. Metrics have earned a reputation as ego-busters, as journalists discover that their readership is considerably smaller and less engaged than they imagined. In meetings and calls I observed, clients called Chartbeat data points on their dashboard “sad” and “super pride-crushing.” Clients’ feelings about their data can become inseparable from their feelings about Chartbeat. An employee who works with smaller, lower-trafficked publishers said the experience of looking at the dashboard can be “harsh,” adding that some elect to stop using Chartbeat before finishing their free trial.

A few Chartbeat employees saw themselves as providers of tough love. One said he tells clients that “facing the low numbers is the first step towards boosting them.” However, in conversations with clients, Chartbeat generally tended to shy away from the role of a purveyor of uncomfortable truths, in large part because the company didn’t want clients to develop negative associations with the product. In meetings and trainings, employees often took a positive tone, even when discussing disappointing or unimpressive numbers. During one training, an employee displayed a graph showing that very few visitors went to a second page on the client’s site after the one on which they’d landed. The employee said that, despite appearances, this wasn’t actually bad, because the client’s landing page had so much to do and look at. “People stay on your landing page,” he encouraged. There were several other instances in which employees were quick to reassure clients that a particular metric wasn’t as bad as it seemed or to redirect clients’ attention from an underwhelming metric to a stronger one.

In addition to trying to take the edge off disappointing metrics, Chartbeat also actively facilitates opportunities for optimism—both in interactions with clients and in the dashboard itself. When describing the considerations that went into the new dashboard, one employee said:

You know, celebrate was one thing. That needs a place in [the product].

CP: When something goes well—

Yeah, yeah! Should we, in our product, be helping them celebrate more, or telling them when to?

Nowhere is the importance of celebration clearer than in the case of the “broken dial.” Chartbeat is priced so that each client has a cap of concurrent visitors that it has paid for; if the number of visitors on its site exceeds that number, the dial “breaks”—that is, the client will see that the dial and the number of concurrents have hit the cap, but the dashboard will not show by how much the cap has been exceeded. The broken dial sometimes results in an upsell, as clients who repeatedly hit their cap can pay to raise it. But even when the broken dial doesn’t directly lead to greater revenue, it has a valuable emotional impact on clients. When the cap is exceeded, one employee explained, “the dial looks incorrect …The product is broken, but in a fun way. If you didn’t have that sort of excitement, it wouldn’t work.”

One client, during a product testing session, articulated just how powerful such excitement can be and how central it is to Chartbeat’s appeal. She said that her news organization had briefly considered discontinuing its account with Chartbeat in favor of a rival analytics service, but within a few days had “crawled [their] way back” to Chartbeat. The Chartbeat employee conducting the session asked, “what is it, do you think, that was the most compelling aspect of Chartbeat?” The client answered:

First of all, if you’re into traffic as most sites are, seeing that big number [recites number of concurrents on her site—750], that’s a really good number. And we’re capped at 2,000 concurrent users, so if we always think—if we’re at 1,999, we always imagine we’re at 2,450 or 5,150, but we probably [just] can’t see it ’cause we’re capped. So we always have that kind of illusion, like that optimism going on.vi

For this client, the broken dial did exactly the opposite of what we typically think of as the role of metrics: Rather than providing unvarnished information about her audience, it allowed her and her team to imagine an audience size that was more than twice the size of their cap, regardless of whether or not the imagined number had any basis in reality. In this instance, Chartbeat’s role as a facilitator of optimism and celebration has taken precedence over its self-described mission to provide readers with an accurate picture of their traffic. Importantly, this is not an oversight on the company’s part but a strategic choice that renders the product more appealing. As an employee put it:

When [a client] does hit a home run, and you see the Chartbeat dial go up, and you see the red line go up, then that euphoria—Chartbeat gets to be part of that experience. So as long as we’re in the room, like high-fiving you, then we get a lot of positive association with that moment.

These findings all contribute to a larger point: While we tend to think of analytics dashboards as a rationalizing force in newsrooms, a tool that applies rigorous, objective quantitative methods in place of the unreliable, unscientific guesswork of the past, it turns out that Chartbeat’s dashboard is designed to play a social and emotional role in newsrooms just as much as a rational one. Everything—from the types of data the dashboard provides, to the features it doesn’t include, to the way in which data is presented, to the interactions between staff and clients—is profoundly influenced by Chartbeat’s need to earn journalists’ trust, prevent them from becoming demoralized, and provide them with an appealing product. Indeed, the company’s very survival depends on its ability to be something editors actually want to use. This is not to say that Chartbeat’s methods for measuring audience behavior are in some way flawed or not objective, or that the company intentionally or cynically manipulates its clients. To the contrary, Chartbeat’s methods are widely considered to be quite rigorous, and most of the staff members with whom I spoke seemed wholly genuine in their belief that Chartbeat’s metrics support and reward high-quality journalism. Rather, the goal here is to illustrate that Chartbeat’s metrics—indeed, all metrics!—are the outcome of human choices and that these choices are in turn influenced by a range of organizational, economic, and social factors.

Analytics at Gawker Media

“I’m actually concerned by the extent to which my emotional well-being is dictated by the number of hits on my posts. I talk to my therapist about it!”

-– Gawker Media writer

There is arguably no contemporary media organization more strongly associated with a metrics-driven editorial culture than Gawker. Throughout its 13-year history, Gawker has put a strong emphasis on numbers, though the company has prioritized different metrics at different times (most notably in 2010, when it switched from a focus on page views to one on unique visitors). Gawker’s focus on metrics was intended to not only boost profits, but also to serve as a positioning device that—along with its sharp, mocking voice and willingness to pay for scoops—set it against the media establishment. At Gawker, metrics have been:

- Prominent: The company famously pioneered the Big Board, a constantly updating screen that hangs over the reception desk on the editorial floor at its Nolita offices. The board, populated by Chartbeat data, displays the top posts by concurrent visitors across all of the sites in the Gawker network. Shortly before I began my research at Gawker, the Big Board was supplemented by a leaderboard that ranks the top writers (staff and non-staff) on Kinja, Gawker’s publishing platform, by the number of unique visitors they have brought to the site in the previous 30 days. Red and green arrows, showing whether individual writers are ascending or descending in the ranks, reinforced the message.

- Public: Gawker is known for its transparency, and many of the company’s metrics are publicly available online, including the Kinja leaderboard16 and graphs17

- Powerful: The company has experimented with a range of traffic-based pay-for-performance schemes over the years. The one in place at the time of my research operated like this: Each site had a monthly growth target of unique visitors, calculated based on its recent traffic. Thus, the sites had different targets depending on their past audience size, but they were all expected to have the same rate of growth. When a site exceeded its target, it received a proportional bonus that the site lead (Gawker’s term for editor-in-chief) could dispense among her writers as she saw fit.vii While monthly bonuses were based on collective traffic, individual traffic numbers were also influential. The company calculates something called an eCPM for all editorial staffers, which is the measure of how many dollars an employee earns in salary for every 1,000 unique visitors her posts bring into the site. Writers were expected to maintain an eCPM no higher than $20, and those whose eCPMs exceeded this for a prolonged period were in danger of being fired. Raises were also closely tied to individual traffic numbers; writers had to demonstrate sustained growth in personal traffic that was roughly proportionate to the raise they were requesting.viii

This metrics-driven approach has paid off: the company’s estimated value is around $250 million; in 2014, it pulled in $45 million in revenue and $6.7 million in profit.18

This moment in Gawker Media’s history lent itself to two major questions: First, if Gawker was indeed an extreme example of the kind of metrics-driven approach that media organizations are increasingly adopting, what was it like for writers and editors to work in this environment? What effect do prominent, public, powerful metrics have on their work and morale, and what might this tell us about the future of digital media as it becomes increasingly measurable and measured? The second question had to do with Gawker’s attempt to pivot away from an exclusively traffic-focused model toward a more interactive and collaborative style of journalism. Much has been written about the struggles of legacy media organizations attempting to adapt to the digital age. But we know less about how digitally native media companies cope with changes in their missions, business models, or field of competitors. What does change look like at a digital media company like Gawker?

The Experience of Working at Gawker

Talking to Gawker writers and editors about metrics, it was immediately clear that traffic data was a central feature of the organizational culture.ix

Data about uniques inspired strong feelings at Gawker. Staffers admitted to feeling “depressed,” “upset,” “worried,” and “desperate” when their traffic or their site’s traffic was low. The flip side, of course, was that getting exceptionally high traffic felt validating, even exhilarating. But the thrill of a hit story was inevitably fleeting: because monthly traffic targets were based on a site’s past performance, high historical traffic meant even higher expectations for future traffic. Even when you were doing well, you could always be doing—and, indeed, were expected to do—even better. One site lead described this unceasing pressure:

It can be quite taxing. I find that the start of every month in my life for the last two years has been stressful, because I start with maybe some of that terror that I had when I was [first] thinking about what it would be like to be a newspaper reporter …“What am I gonna write about?” Well now it’s, come March 1st, “well, hope we do as well in March as we did in February.”

A writer described a similar feeling, which he linked to Chartbeat specifically:

Chartbeat is rough because it’s relentless. There’s never gonna be a time when you can close your MacBook and be like, Chartbeat’s all set, our traffic’s good, we’re ready to go. You can always do something else, or post something else to Facebook to see if it sticks, or try tweeting a story again to see if maybe it’ll get pickup now instead of this morning.

The never-ending cycle of highs and lows, facilitated by real-time analytics tools like Chartbeat and expressed materially in bonuses and raises (or the lack thereof), meant that working in editorial at Gawker could be an emotional roller coaster. In the words of a site lead:

When traffic is just average or low, or if we have a really spikey period and it goes down to what it was pre-spike, I get upset. I feel like I’m not good at my job …I notice it all the time.

The ups and downs could also be highly addictive. Some staffers made explicit analogies to drugs when discussing metrics. The writer who called Chartbeat “relentless” also admitted to having been a “Chartbeat addict” at previous digital media jobs. He said he was trying to limit his exposure to the dashboard, with limited success: “At Gawker Media it’s like I’m a cocaine addict on vacation in Colombia.” Others compared the perpetual hunt for traffic to playing a game or gambling.

It is perhaps not surprising, then, that when I would ask staffers what personal qualities were needed to thrive at Gawker, nearly all of them mentioned competitiveness. As an editor succinctly put it, “if you aren’t hard-working or hyper-competitive, I can’t imagine how you would work here.” Several employees cited their backgrounds in extracurricular sports and video gaming as experiences that had prepared them for Gawker’s company culture. While Gawker’s reputation for being metrics-driven undoubtedly causes it to attract already competitive employees, the looming presence of the Big Board and the Kinja leaderboard in the office intensified this trait and, as one writer put it, “massaged [it] into productivity.”

But the leaderboards ranking stories and staffers don’t just harness employees’ competitive tendencies; they shape the very nature of competition in the media field, namely by turning it further inward. In Deciding What’s News, his 1980 ethnography of Time, Newsweek, CBS, and NBC, sociologist Herbert Gans documented the extreme lengths to which these rival magazines and news networks would go trying to outpace each other in scoops and audience growth.19

Of course, newsrooms have always had competitive internal dynamics. But metrics can highlight and intensify them. For instance, a staffer at Jezebel, Gawker’s site devoted to feminism and women’s issues, fervently wanted to surpass the traffic of Deadspin, the sports site, but evinced only an abstract curiosity about the traffic of other women’s sites, like XOJane. This is largely attributable to the fact that Gawker Media employees did not generally know the traffic figures of other companies’ sites beyond the broadest strokes or estimates. A staffer at Kotaku, Gawker’s gaming site, explained:

I don’t even know what other gaming sites are doing. I also don’t care, because I know that this sports site [Deadspin] and this politics and celebrity gossip site [Gawker] and this tech site [Gizmodo] that are part of my company …I know how well they’re doing. I see how much they’re growing every month. And if sites about all these other topics can grow to the extent that they’re growing, then why can’t my site?

It is striking that an employee at a site with a relatively niche audience would hold it to the same standard of growth as sites about more mainstream topics like consumer technology or celebrity gossip. But the intention of the Big Board and the Kinja leaderboard was precisely to render seemingly dissimilar sites and writers comparable according to the same metric and thereby place them in competition. This dynamic occasionally caused bad blood between coworkers and resentment from the smaller sites. During the time I spent in the online group chat of one of the company’s smaller sites, writers expressed annoyance that a writer for a larger site had published a post about a video their site had covered first, rather than simply “splicing” their post (and thus ensuring that their site got the additional traffic).

Given the prominence, publicness, and power of metrics at Gawker, what kinds of actions did editors and writers take to boost their numbers? My research revealed three main effects of Gawker’s metrics-driven culture. First, writers and editors had a tendency to go with what works, or had proven to work in the past. A writer ticked off the types of posts that reliably “do well” on her site: “People love unhinged letters …Unhinged sorority girl! Unhinged bride! [Or], ‘look at what this douchebag wrote me,’ …And people like cute things that kids did. People like heartwarming videos with inter-species friendships.” In the event that a post outside the realm of surefire traffic-getters became a surprise hit, a site would try to follow up on it or replicate it. One site lead, after being shocked by the traffic garnered by a short post about the upcoming series finale of a popular TV show, told the writer to do a follow-up post immediately after the final episode aired: “[I said], ’I need you to cover this first thing in the morning. I don’t care what you write, but you need to cover it.’ ”

Second, writers posted very frequently. While most staffers could rattle off a list of topics that could be counted on to get good traffic, many also stressed that traffic could be highly unpredictable. Nearly everyone I spoke to could cite examples of posts whose traffic far exceeded—or, in a few cases, gravely disappointed—expectations. This element of randomness or surprise meant that the only way to guarantee higher traffic—both individual and site-wide—was to post as much as possible. Many sites had adopted this strategy. As a writer put it, “it’s more or less like playing the lottery. You pick your numbers and you’re diligent about it and the more lottery tickets you buy, the more likely you are to hit it big.”

As this writer acknowledged, though, there were costs associated with frequent posting: “[Traffic] compels me to produce more. However, producing more, blogging more, keeping the post count up, necessarily means that I don’t take time to work on the longer, slower, reported-out features.” This was a recurring theme. Site leads said they were happy when writers did manage to produce longer features or essays, even when these were unlikely to attract major traffic. Yet they acknowledged that this could cause problems. In the words of one site lead: “Sometimes there are things that are really long beautiful pieces that are very thought out and only do 10,000 uniques over 24 hours, and that kinda sucks. But I wouldn’t change it. It’s just the pressure now to be like, OK, what are we gonna do now to make up for that?”

The extensiveness of metrics-driven employee monitoring could easily give the impression that Gawker was an oppressive work environment. Some commentators and reporters have characterized Nick Denton as running a “digital sweatshop”; listening to writers and editors speak about their efforts to keep pace with growth expectations, it was not hard to see why. Yet some staffers had turned down offers from legacy media organizations where there was far less of an emphasis on traffic; others had left Gawker for such organizations only to subsequently return to the company. This pattern has become so common that Capital New York gave it a name: the Gawker boomerang.20 When staffers were asked why they return, or why they chose to build their careers at Gawker in the first place, the answer was nearly always the same: writers and editors cherish the freedom and autonomy they feel they have at Gawker. When John Cook departed from Pierre Omidyar’s embattled First Look Media, he tweeted, “there’s more autonomy at gawker than any other editorial shop, First Look or otherwise—that’s the operational principle.”21

[At Gawker] you’re really visible and you’re allowed to be yourself. And I think that’s one of the great things about writing for any of the Gawker sites, is that they encourage you to have an opinion and to have a voice. Whereas at [one of these magazines], they’d be like, “be yourself, but be yourself through us.”

A site lead who had returned to Gawker after working in magazines echoed this point: “Nick lets us do whatever we want. We can write whatever we want. We can take the site wherever we need to go.”

Obviously, the Gawker staff is a self-selecting group: those who apply, get hired, and stay at the company (or return to it), are unlikely to find metrics overly oppressive or debilitating. Even so, Gawker’s multiple systems of metrics-driven monitoring could make employees’ paeans to their editorial autonomy seem hollow or even deluded. After all, site leads were free to take their sites “wherever they need to go” only as long as they kept their traffic numbers up. But to see employees’ perceptions of editorial autonomy as a form of false consciousness oversimplifies the issues at stake. Statements like Cook’s raise a broader question: what is the meaning of editorial freedom in a digital media landscape saturated with metrics? Many online-only media companies, including Gawker, have dispensed with, or at least scaled back, the stylistic and ethical norms of twentieth-century journalistic professionalism, such as objectivity, nonpartisanship, and the prohibition on paying for scoops. They also tend to have a flatter organizational structure than legacy media organizations, such that writers face far less editorial oversight. Yet such freedoms coexist with levels of metrics-driven surveillance that would be unthinkable at more traditional news organizations like The Times. This suggests that the contemporary digital media landscape encompasses multiple conceptions of editorial freedom—and those who populate it have conflicting notions of what constitutes the most onerous constraints for working journalists.

Changing a Metrics-driven Culture Can be as Difficult as Changing a Legacy One

The centrality of metrics to Gawker’s organizational culture meant that behaviors that were hard to quantify were also hard to incentivize. This came across most clearly in discussions of Kinja, Gawker’s publishing platform. Kinja, which allows users not only to comment on posts on Gawker sites but also to publish independent posts of their own, was born out of Denton’s vision of collaborative journalism—the idea, in short, that the best stories emerge not from the dogged efforts of a lone reporter but from the collective work of a writer and her devoted audience, which provides tips, serves as valuable sources, engages in spirited debate, or moves the story forward in other ways.

For Denton’s vision to be realized, Gawker staffers had to be highly interactive with their audience in the comments section of each post. But this presented a major problem for Gawker’s management. Over the years, employees had been conditioned to use numbers as an important gauge of their job performance, yet interactions on Kinja were not easily quantified. There were attempts to do so: During my time at Gawker, then-editorial director Joel Johnson emailed each site’s editorial staff about a new policy that writers were expected to participate in the comments section of at least 80 percent of their posts (and called out, by name, those who had failed to meet the target). However, there was no systematic way to measure or quantify the quality of these interactions, and some writers told me it was easy to hit the 80 percent target by responding to comments with, “great point!” or a similarly superficial contribution. To spend more time engaging with commenters, they said, would decrease their post count, which could, in turn, depress their number of unique visitors and their site’s chance of getting a bonus.

To address these tensions, Gawker executives introduced a “Kinja bonus,” modeled after the uniques bonus, in an effort to boost writers’ engagement with the comments. But there was no transparent, mathematical way of allocating the Kinja bonus, which led writers and site leads to question its legitimacy and fairness. As one site lead explained:

Every site gets 1 percent or 2 percent or maybe 0 percent of their monthly budget if there’s been good Kinja participation, which, how is that judged? Well, they don’t actually have a way to count this yet. So this metrics-driven company is in this position where they value this thing because, in theory, it will lead to greater health for the platform and the company, but they have no numerical proof for it. x

Even if Gawker managed to make the expectations and incentives around Kinja interaction more straightforward and transparent, my interviews indicated that staffers would continue to resist the shift from a focus on mass traffic to a focus on interaction. Many writers and site leads had fraught, if not downright hostile, relationships with commenters. Said one editor when asked about commenters: “I hate them. So much. I fucking hate them. I’ve always hated them. They’re the worst.” Writers and editors alike complained about finding themselves on the receiving end of a daily onslaught of negative or critical comments—and for female employees or employees of color, these could veer into harassment and threats. Some writers coped by avoiding comments altogether. This group was particularly dismayed by the new focus on Kinja interaction; they felt as though they were being told that enduring daily harassment was now a part of their job.xi

Interestingly, some employees turned to metrics as a way to counter the psychological toll of negative comments. As the editor lead who has “always hated” commenters put it:

We broke 9,000 [concurrent visitors] earlier today, so that was awesome. I take screen cap[ture]s of that. That is a reminder that I can do this …It doesn’t matter if I have someone screaming at me [on Twitter] at 7:30 in the morning. I’m good at my job …And if [my site] was really downhill, more and more people wouldn’t be reading it!

For writers facing the hostility of online commenters, traffic numbers can operate as a source not of stress but of solace and validation.xii

SEO type stuff, but more like headline tricks, tweet tricks, [all of which were a] precursor to the awfulness that is Upworthy. Like all those tricks work and they’ll get you traffic, but more mature sites, Gawker media sites, realize that there has to be a balance between playing to the numbers but also paying attention to quality, and having some really simple rules in place as to what you will and will not do for traffic.

In his much-discussed post “On Smarm,” Gawker.com editor Tom Scocca argued that Upworthy and BuzzFeed, both top Gawker competitors for social traffic, epitomize smarminess online, defined by Scocca as “a kind of performance, an assumption of the forms of seriousness, of virtue, of constructiveness, without the substance.”22 Denton, in his 2013 year-end memo, acknowledged that Gawker was “not completely averse to crowd-pleasing,” but called BuzzFeed and Upworthy “the most shameless” in their ploys to get traffic, adding “the crowd will eventually choose the juicy truth over a heartwarming hoax.”23

Analytics at The New York Times

“It’s very easy for everybody to read their own agenda into the numbers.”

-– New York Times editor

If Gawker is an organization whose culture is steeped in metrics, The New York Times is the opposite: an organization whose 164-year history, prestigious reputation, and majority single-family ownership have long buffered its newsroom from the kinds of commercial considerations that metrics represent. In past years, representatives of The Times have publicly taken a dismissive posture toward metrics. “We believe readers come to us for our judgment, not the judgment of the crowd,” said former executive editor Bill Keller in 2010. “We’re not ’American Idol.’ ”24

The confluence of The Times’s longstanding culture and its current economic reality has led to a fraught relationship with metrics. In The Times newsroom, the use of metrics was:

- Restricted: Though The Times subscribes to several analytics tools, such as Chartbeat and Google Analytics, only staffers in certain roles and departments were authorized to view them. Similarly, while the most-emailed list is publicly viewable on The Times website, only a small number of staffers received a regular email showing how many times each story on the list had been emailed. Access to analytics was largely aligned with staff hierarchy—as a general rule, editors could see metrics and reporters could not. However, there were exceptions: some relatively junior online staffers (e.g., web producers) had access to analytics, and access was more widely distributed in online-only departments, such as interactive news.

- Discretionary: It was largely left up to those staffers who had access to metrics to decide how (if at all) they wanted to consult and use them. There were no newsroom-wide expectations around metrics, nor were there formalized systems for asking questions of data or drawing conclusions from it.

- Rare: With the exception of online-only items such as blogs and interactive features, audience metrics did not play a major role in editorial decision-making at The Times. For instance, while page one placements were a part of reporters’ yearly evaluations, online metrics (including home page placements) were not.

To be sure, The Times is unique—or at least, atypical—in many respects. But the organization’s extraordinary prestige and strong sense of journalistic professionalism, coupled with its ongoing financial challenges, mean that highly relevant questions about editorial metrics appear in especially sharp relief at The Times. These range from the simple (What do metrics mean? Who should be in charge of interpreting them?) to the complex (How can journalists take metrics into account without sacrificing their professional integrity and sense of civic responsibility? What is the right balance to strike?).

The Thinking Behind Restricted Access to Metrics

At a time when even legacy newspapers like The Washington Post have screens showing traffic numbers in the newsroom, The Times newsroom is notable for the conspicuous absence of such displays. While editors had access to analytics tools, including Chartbeat, reporters did not. Some reporters I spoke with were indifferent about how metrics rated their work, but many expressed a desire to see traffic data:

I don’t easily know how many people click on my stories. I would be curious to know that but I don’t have a way of easily knowing.

I would love to know [by] what paragraph my readers start to give up on me, because you know they’re not reading ’til the end, but we write it like they are, right? …And traffic could unlock those answers.

Why did The Times restrict reporters’ access to metrics? Two answers emerged in the course of my research. First, there was a concern that seeing metrics could lead reporters astray from their independent news judgment. Instead of covering topics that are important or newsworthy, they would start to focus on more frivolous subjects that are guaranteed to be popular. Said one reporter:

It would be a bad idea for us to be choosing stories based on how many people were reading them …I mean, if you go down that road, then you end up writing a lot about, you know, Angelina Jolie or whatever.

While interviewees often invoked this fear, it was usually voiced abstractly, as a hypothetical, worst-case scenario. The Times’s history, single-family majority ownership, and longstanding organizational culture made the adoption of purely metrics-driven decision-making seem highly unlikely to many staffers. “There’s no danger of that at The Times,” said one reporter, articulating a sentiment I commonly heard in interviews, “because the entire philosophy of the place and …woven deep, deep, deep into the fabric of the place is opposed to that.”

The second—and in my view, more important—reason The Times restricted reporters’ access to metrics was because of concerns that they would misinterpret the data. We tend to assume that the meaning of metrics is relatively straightforward: Story A got more page views than Story B; Story B got the most Facebook shares of the week, and so on. But several Times staffers commented that they found metrics quite difficult to make sense of, let alone act upon. This is not because most journalists are “bad at math,” as the late Times media columnist David Carr put it,25

If one story gets 425,000 hits and another one gets 372,000, is that meaningful, that difference? Where does it become important and where doesn’t it?

An editor echoed this theme of interpretive ambiguity:

When you’re looking at a raw number, it’s hard to know how that fits into what you would expect …It’s almost like, you rarely have an apples to apples comparison…. There’s so many other things kind of confounding it.

The fact that audience metrics could be interpreted in multiple ways, depending on who was doing the interpreting, was a source of concern for editors. Some worried reporters would use metrics to challenge their decisions. For instance, when asked why The Times newsroom restricted access to analytics, one editor described his annoyance at what he saw as reporters’ misreading of the most-emailed list (which, by virtue of its place on The Times home page, is one of the only metrics to which reporters had regular access):

People in here will say, “oh my gosh, look, my story’s number one on the most-emailed list, you should put it on the home page!” Well, no, we’re not making judgments based on that. We’re making judgments based on …what are the most interesting, or the most important stories for our readers.

To this editor, the fact that reporters drew incorrect conclusions from the most-emailed list meant that they should not have access to more data. A Chartbeat employee had encountered a similar line of thinking among clients. While creating an earlier version of the company’s dashboard, she had worked with a number of legacy news organizations that didn’t provide universal access to metrics; they gave it instead only to high-level editors for whom there was:

no fear about them misusing data, abusing data. And “abusing” means that they don’t know how to read it, therefore don’t understand it, therefore are …gonna make the wrong, like incorrect assumptions, or use it to their advantage.

There was also a concern among editors that metrics could demoralize reporters by disabusing them of common (though incorrect) print-era assumptions about their audience. A member of the internal team that spent six months studying the newsroom to produce The Times’s Innovation Report said the group had come across this fear:

Reporters …in the print universe, they’ve had circulation numbers. And you push them on this and they know it’s not true, but they all believe that the circulation number is sort of how many people read their story …They kind of really do have this inflated sense of readership. So there’s a real worry that delivering them hard data on digital readers will be demotivating.

In sum, metrics are a source of anxiety at The Times, not only because of their power to influence content, but also because of their potential impact on the organization’s internal dynamics. Metrics provided an alternative yardstick—aside from editors’ evaluations—by which reporters could judge the worthiness of their stories and their job performances more broadly. The data therefore threatened to undermine not only news judgment, but also the traditional hierarchical structure of The Times newsroom, in which editors were the final arbiters of the nebulous quality that is “newsworthiness.” If editors alone had access to metrics, they alone could control the way in which the data was interpreted and mobilized.

It is a common conception that data analytics will displace established “experts” who base decisions on their own experience, intuition, and judgment. Economist and Yale Law professor Ian Ayres concisely articulates this view: “We are in a historic moment of horse-versus-locomotive competition, where intuitive and experiential expertise is losing out time and time again to number crunching.”26

It is not hard to see how a version of this narrative might apply to journalism. Editors could (and, at many organizations, do) find themselves increasingly displaced by metrics that demonstrate what content is winning large audiences and, in some cases, make suggestions about placement and story assignment. An online editor at The Times succinctly voiced this anxiety:

Really the only thing an editor has—like their full job is based on their judgment, ’cause that’s really what they do, is they just sit and use their judgment to edit stories and decide how important they are and where they should go on the site. And so, replacing that with metrics is some sort of massive threat to their livelihood and value in the job.

Thus, Times editors restricted access to metrics in order to minimize the perceived danger presented by the data. At the same time, it was clear to editors that metrics could be quite useful as a management tool, and many reported employing it in this way.

The Invocation and Disclosure of Selective Metrics as a Management Tool

The fact that reporters did not have regular access to analytics is not to say they were never exposed to this data. Obviously, reporters could always see the limited metrics that are made public on The Times site, such as most-emailed and most-viewed. While editors sometimes expressed annoyance or bewilderment at reporters’ interest in the most-emailed list, they also regularly congratulated reporters whose stories made the list. As one reporter explained:

It’s absolutely routine now that when any desk head sends out their “what a great job we’re doing” [email], it will go, “it was a great week, [so-and-so’s] story shot to number one most-emailed in three-and-a-half hours.”

Again, this suggests that it was not the most-emailed list per se that editors objected to—rather, it was the fact that reporters sometimes interpreted the list in ways that editors did not approve of or agree with.

In addition to invoking the most-emailed list, editors often shared carefully curated proprietary metrics with reporters, often to accomplish particular management goals. One such goal was to increase reporters’ enthusiasm for writing content that would appear only on The Times website, not in the print publication. Researchers studying The Times, such as Nikki Usher and the internal team that produced the Innovation Report on the organization’s digital challenges, have found that The Times continues to locate most of its prestige in the print edition. My own findings strongly corroborated this. As an editor explained:

We have this tradition at The Times that when somebody gets a story on page one for the first time, we order a modern-day version of what used to be like the page one plaque during the days of lead type and, you know, it’s like this aluminum sheet with the page one etchings on it, which is sort of our honorary acknowledgement that they got a story on page one …Nobody wants to get a plaque that shows their story on the home page of The Times.

As noted above, this favoring of the print edition over the online one had material implications for reporters. An online-oriented editor recounted employee evaluations from her time as a reporter:

In my annual review, even though I was an exclusively digital person who was supposed to be pioneering things, there was no mention made of anything [other] than the number of stories I had on page one. That is still the metric that is used for reporters. Over and above everything else.

Given the higher status of the print edition relative to the online one, it was unsurprising that some reporters were not particularly eager to write online-only content, such as blog posts. This could be problematic for editors, who needed to fill The Times’s sprawling website with content, much of which would never run in the print paper. Metrics came in handy as a way to increase reporters’ enthusiasm for writing online-only content, and editors often used them to do just that. In the words of an editor (the same one who was annoyed when reporters advocated for home page placement based on their story’s appearance on the most-emailed list):

One of the things that we’ve tried to do with [audience data] is to use it for other purposes. At The Times being on A1 is a hugely important thing and a huge accomplishment. We’re trying to impress upon people the value of being on the home page, too. And so if you can say, “hey, thought you’d wanna know—your story was being read by 8,000 people at nine o’ clock this morning …” or something like that, then the point of that is just to try to emphasize to people the value of being on the home page.xiv