Sign up for the daily CJR newsletter.

PHOTOGRAPHER WILL STEACY set out in 2009 to “tell an inspiring story of a newsroom”—that of the Philadelphia Inquirer, which made its home on North Broad Street, inside the “Tower of Truth,” for nearly 90 years. However, Steacy’s project took an unexpected turn in 2011, when the Inquirer laid off his father, Tom, an editor who had worked for the paper for almost three decades. By the time Steacy’s work on the project was done, budget woes had forced the Inquirer from its longtime home and its staff had been slashed.

In what perhaps is a sign of the times in newspapers, what began as a feel-good inspirational project has instead turned into an ode for journalism—all at an outlet that is intensely personal for the photographer behind it.

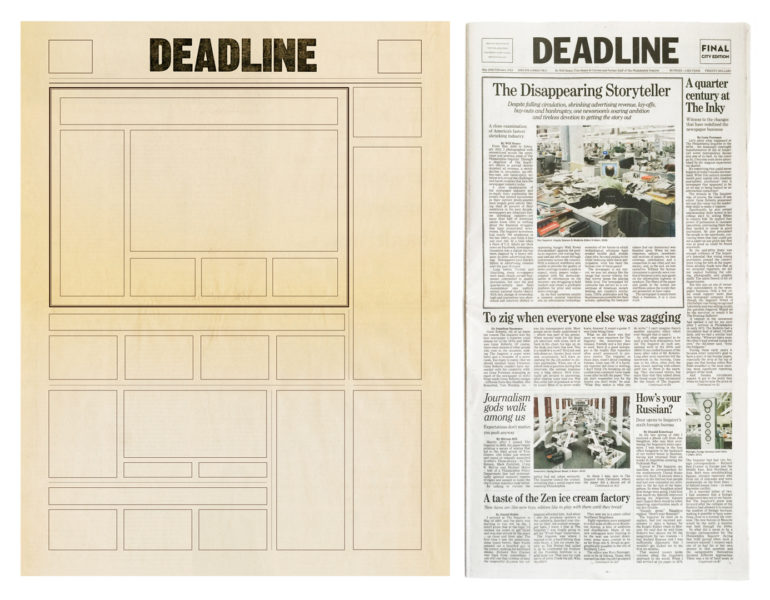

“DEADLINE” FEATURES TWO VOLUMES: a book of color and black-and-white photographs with an introductory essay by acclaimed Inquirer editor Gene Roberts, and an 80-page, five-section broadsheet newspaper filled with essays by current staffers and alumni, as well as Steacy’s photos. “Deadline” strikes a balance that is rare among journalism memoirs and histories: The project is a gratifying study of how journalism is done and undone, with dozens of behind-the-scenes tales told by those who did the work rewarded by 20 Pulitzers and dozens of other prizes. But Steacy’s photos of his own family and photos and essays involving the extended Inquirer family also make “Deadline” intensely emotional and personal.

Avery Rome, the last editor of the defunct Inquirer Sunday magazine, praises “Deadline” for its “egalitarian nature” at a time of cultural skepticism and even antagonism towards journalists’ work. (A recent New York Times story is headlined: “Journalism In the Age of the Body Slam.”) Several photos—empty trays where ad copy used to sit, a staff portrait with crosses drawn over the faces of departed colleagues—struck her as “really elegiac and so sad.”

But she also saw Steacy’s work as validating the work of journalists. “We’re the everyman,” says Rome. “And Will’s trying to tell the greatest truth, which took a certain valor.” As a whole, says Rome, “Deadline” expresses “the truth of an industry”—a truth that includes the impact of a transformation on its workers.

Throughout “Deadline,” personal and professional narratives are bound. James Steele recounts the “vague hunch” that spurred his coverage of the 1973 oil crisis with reporting partner Donald Barlett. That hunch launched a reporting partnership that spanned more than three decades and yielded two Pulitzer Prizes, two National Magazine Awards, and numerous investigative breakthroughs.

Gene Foreman—a former managing, deputy, and executive editor—provides a detailed walk-through of his quarter-century with the paper, in which the Inquirer went from local runner-up in the daily newspaper wars to a Pulitzer factory, then went through bankruptcy and financial decline. Such essays carry their weight into the present day; as Foreman notes in his kicker, “There persists a tradition of excellence that is proving hard to kill.” (The Inquirer’s current fortunes may only improve: The Lenfest Institute for Journalism, a nonprofit that owns the Inquirer’s parent company, recently announced donations to support its journalism of at least $60 million.)

David Cay Johnston, the investigative journalist who recently acquired pages of Donald Trump’s 2005 federal tax return, says the project “gives a record to understand how this single newspaper and its leaders built an institution that was a model for serious journalism.”

“I hope copies are in journalism school libraries everywhere,” says Johnston.

At the moment, this seems unlikely: Steacy published just 1,200 copies of the book and 2,000 copies of the newspaper, and most have been sold. If “Deadline” is an important contribution to how the public understands the work of local journalists, then it’s a shame to think it won’t be more easily accessible.

“Projects like this are more important than they were a few years ago,” says Allison Steele, daughter of the investigative reporter and a current staffer at the Inquirer. “There’s an opportunity for journalists to educate the public about what we do.”

She contributed an essay to “Deadline” in which she recounts visits to the newsroom with her father during a time in her childhood when she only “knew his work involved a lot of time on the phone, many piles of paperwork and stacks of books.”

“The city is changing,” Steele tells CJR. “One of the challenges we’re facing is how to reach members of the community who aren’t getting coverage, whose interests aren’t being represented as well as we could.” Newsrooms in many communities are up against the same challenge, Steele adds.

“Things change, they don’t stay the same,” she says. “Hopefully there’s another golden age coming.”

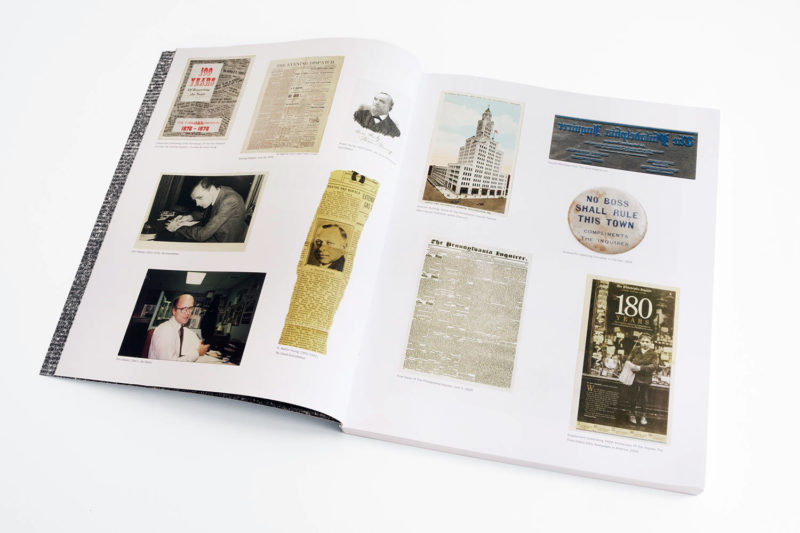

WHEN STEACY BEGAN WORKING on “Deadline,” he learned that his family included an unbroken five-generation chain of newspapermen that began with his great-great-great-grandfather, founder of The Evening Dispatch in York, Pennsylvania. Discovering 150 years of journalism in his family, and seeing his father forced into retirement, spurred Steacy to develop his project’s intensive first-person perspective.

“Deadline” is filled with journalism artifacts uncovered by Steacy in the attic of his family’s Philadelphia home: rejection letters, black-and-white newsroom portraits. These are complemented by dozens of moody newsroom tableaus shot while the economic downturn bore down on the nation’s third-oldest newspaper.

Since publishing “Deadline,” Steacy himself has changed. A career photographer, he currently writes for NowThisNews, which publishes via Snapchat. “I’ve gone from working on telling a story over five years to telling a dozen in a day,” he says.

Steacy recognizes the irony in working for a digital-only news organization. “It’s the polar opposite, a stark contrast” to the Inquirer he documented so meticulously. Still, he says his father was proud to hear that his son entered the family business. “In his eyes, taking this job made me sixth generation.”

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.