Sign up for the daily CJR newsletter.

The gang rape last week of a northern Indian woman from the untouchable caste made headlines in India’s influential English-language press. The case was striking because the woman had been raped before by the same group of men; the latest attack being seen as an attempt to prevent her from testifying in court. But after a brief flurry of articles, newspapers soon moved onto other developments in the restive state of Kashmir.

This was in stark contrast to the mass coverage that followed the 2012 gang rape and murder in Delhi of a student thought to be middle class. Then, India’s English-language papers appeared to act as the mouthpiece of widespread public demands for changes in awareness, attitudes, and reactions to sexual violence. Four years on, these cries for justice have been replaced by occasional spikes of outrage as new rape cases are reported.

So why has the blanket media outcry that followed the Delhi gang rape been replaced by a less consistent response? The answer may lie in a study of how the Delhi gang rape was reported by the English-language press. I conducted just such a study as a fellow at the Shorenstein Center on Media, Politics and Public Policy at the Harvard Kennedy School of Government.

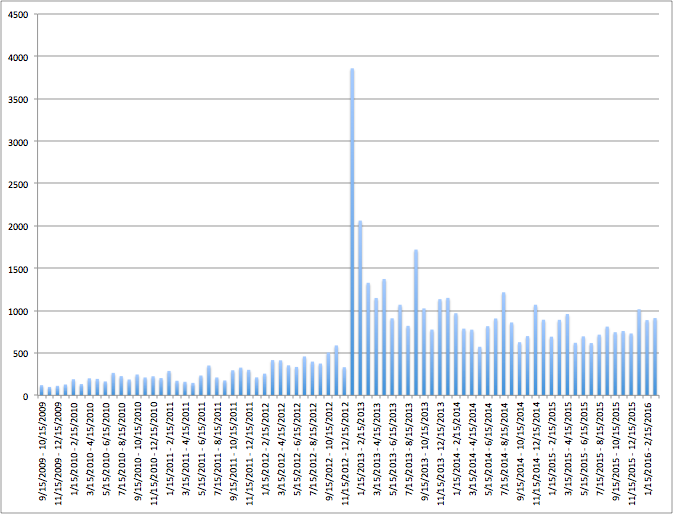

A data analysis of India’s four leading English-language newspapers–The Times of India, The Hindustan Times, The Hindu and The Indian Express–shows that the 2012 Delhi gang rape case triggered a significant increase in rape coverage in India. A keyword search for “rape” and “gang rape” in the 39 months before and after December 2012 shows a huge spike at the time of the attack, and a marked increase afterwards.

Figure 1: Number of times the terms “rape” or “gang rape” appear in The Times of India, Hindustan Times, The Hindu and The Indian Express, 2009-2016.

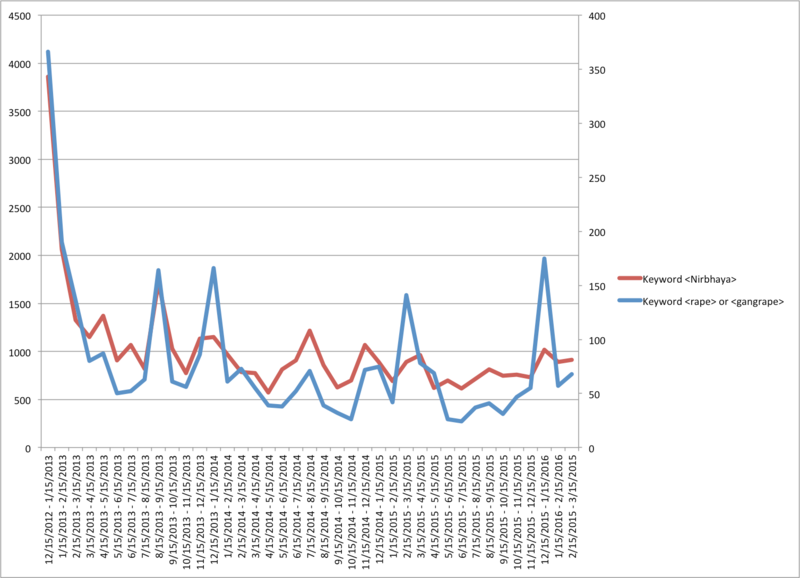

A further analysis of the terms “rape” and “Nirbhaya”–a name used by the press to describe the Delhi victim–shows that coverage of the “Nirbhaya” case spiked in tandem with rape coverage, but that general rape coverage has also persisted at a higher rate than previously. So if India’s English-language press are covering rape more than they did four years ago, why is sexual violence still failing to generate sustained media attention?

Figure 2: Number of times the term “Nirbhaya” vs. terms “rape” or “gang rape” appear in The Times of India, Hindustan Times, The Hindu and The Indian Express, 2009-2016.

When details of the December 2012 gang rape first began to filter into India’s newsrooms, editors were faced with the decision of whether to run the story on the front page. Three facts stood out: the victim was a student, she had been to an upmarket shopping mall before she was attacked, and she had also just watched an English-language movie. These factors marked her out as a middle or upper-class Indian woman, which in turn made her story more compelling for the wealthy, urban readership of India’s English-language press. “There is this term we use called PLU–it means ‘people like us,’” says former Times of India reporter Smriti Singh. “Whenever there is a murder or rape case involving a female, in your head you have a checklist as to whether the story qualifies to be reported or not.”

Being a PLU, or of the right socio-economic class, means your story is far more likely to be covered by the English-language press. On the surface, the Delhi student appeared to be the ultimate PLU victim. In fact, as details emerged of her family background, it became clear she was not from the established middle class, but was aspiring to transcend her working class roots as the daughter of a laborer. But by the time this was known, the case was unstoppable. Every newspaper wanted as much detail as they could get about the case.

“There is a vast country beyond Delhi and Mumbai, and there is a lot of crime happening there, and those people are in need of exposure and a platform,” says Priyanka Dubey, a reporter who describes herself as a lower-middle-class Hindu who has struggled to have stories on sexual violence published in the English-language media.

Two other factors led to the Delhi gang rape dominating the English-language press: the victim was seen as blameless for her crime, and the crime was especially violent. The Indian media often reports rape as a crime of lust and passion, in which sexually precocious women can provoke men to attack. There is a lack of analysis of the complex patriarchal, societal, and economic factors that underlie much sexual violence. In the case of the Delhi rape, the victim was brutally raped after the innocent action of boarding a bus to take her home. The dispute over victim and perpetrator accounts that often accompanies rape was absent in this case. The victim was heralded as “Nirbhaya”–the braveheart or fearless one. There was no ambiguity in her status as a heroine who could be celebrated.

Similarly the extreme nature of the violence against the victim meant that her story could be championed by the press, which highlighted the visceral details of how she had been repeatedly raped and sodomized and how the perpetrators had penetrated her with an iron rod and pulled out her intestines. “The story was inherently sensational and the coverage was driven by the conviction that people were very curious to know about it and there was competition with other newspapers,” says former Times of India editor Manoj Mitta. This extreme violence has now become a benchmark for reporting new rape cases in India.

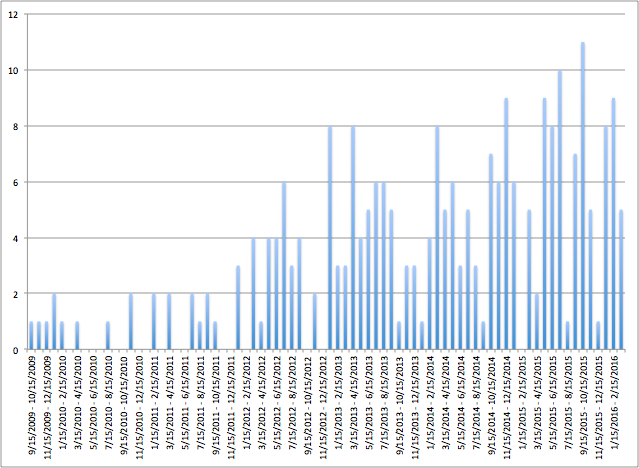

It is now more than four years since the Delhi gang rape, and although incidents like the attack last week have gained press attention, no other case has caught the public imagination in the same way as “Nirbhaya.” In fact, there are signs that India’s English-language press may be reflecting a less sympathetic view towards rape victims. A data analysis of the term “false rape” (where a victim withdrew their claim before or during prosecution) shows a small but significant rise in reports on this issue since 2012.

Figure 3: Number of times the term “false rape” appears in The Times of India, Hindustan Times, The Hindu and The Indian Express, 2009-2016.

Journalists have attributed this rise to the persistent Indian narrative that women are prone to file false cases when they have been caught having a sexual relationship outside marriage, let down after a promise of marriage, pursuing a personal vendetta, or trying to extort money.

Although the coverage of the Delhi gang rape showed that Indian English-language newspapers were prepared to report on and highlight the issue of sexual violence, much could be done to improve how publications tackle this issue. There could be better press regulation to prevent salacious and sensationalized coverage, greater sensitivity in reporting, the inclusion of non-PLU cases, the appointment of specially-focused gender reporters and the reframing of rape from a lust crime to a political, economic, and social phenomena. Although rape is now news in the Indian press, it may take many years before this issue is given the sustained and enlightened attention it deserves.

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.