Sign up for the daily CJR newsletter.

In October 2014, journalist Tania Montalvo walked into an editorial meeting at Mexican news website Animal Político with a document from the country’s Attorney General’s Office. The two-page document she’d obtained through Mexico’s freedom of information law shows one column with the names of nine cartels, a second column with the criminal groups tied to each cartel, and a third column with the Mexican state where each criminal group operates.

Apart from providing a list of names and locations of the criminal groups active in the country, the document also debunks common myths perpetuated by politicians—that organized crime doesn’t have a presence in Mexico City, for example.

But rather than publish an exclusive with a quick infographic, Animal Politico’s executive editor, Dulce Ramos, decided to hold onto the document. She wanted to gather more data and create an interactive piece of journalism that would take readers back several decades and help them understand how Mexico ended up with nine active cartels and 43 criminal groups.

Ramos had a scoop, but she also had a problem. When a document is produced in response to a request under Mexico’s transparency law, it becomes available to the public. Soon, several traditional media outlets got copies of the document and published articles about it. “That was disappointing at the beginning,” Ramos says. “But we tried to remain calm and say: ‘What we want to do is different. We’re not just looking at this document, we’re making requests for [data] that looks forward and backwards in the history of drug trafficking.”

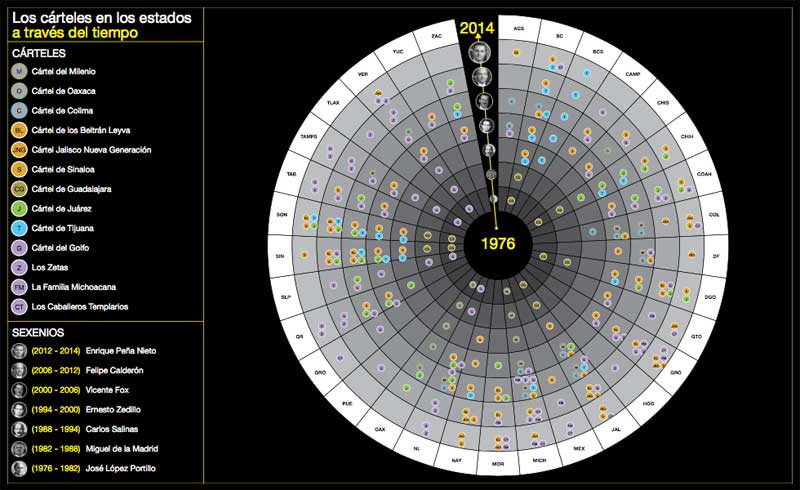

An interactive visualization shows the evolution of cartels in each Mexican state during the last seven administrations.

Narcodata was released a year later, in October 2015, as a data-driven platform with interactive timelines, graphs, and videos. Ramos wants all visitors—journalists and the general public—to feel that they have a better understanding of the history of organized crime in Mexico after interacting with the website.

“The government has been negligent in generating constant, organized and transparent information,” Ramos explains. She also believes that every article about narco violence deserves context. “We wanted to fill that gap somehow.”

Journalists covering the escape of Sinaloa cartel’s Joaquín “El Chapo” Guzmán, for example, can go to Narcodata to find a story on the state of the Sinaloa cartel during the presidency of Enrique Peña Nieto (here’s an English-language version of that article). Furthermore, the team’s methodology is open to the public, so journalists can consult the raw data and sources that were used to create Narocadata’s content to enhance their own reporting.

Media researcher Maria Elena Meneses, who teaches at the Monterrey Institute of Technology, says Mexican journalists don’t often use data to report about violence and crime. Instead, such news is generally accompanied by gruesome photos and information that are anonymously sourced or unverified. Many Mexican journalists, especially those working in the states hardest hit by organized crime, lack the skills needed to work with data, Meneses explains.

Mexico has lagged behind other Latin American countries when it comes to data-driven journalism, according to the 2014 Iberoamerican Data Journalism Handbook, a guide written by journalists, designers, and developers from Spain and Latin America. But that’s slowly changing. Last year, Mexican news website Aristegui Noticias published an investigation called Mexican President’s ‘White House,’ which revealed that a government contractor had built president Enrique Peña Nieto a mansion worth nearly seven million dollars. The team used Mexico’s transparency law to access key documents. Additionally, Mexican newspaper El Universal has created a special section dedicated to data journalism, and a team of Mexican reporters is looking at corruption in Congress in a data-driven website called ¿Quien Compró? (“Who Bought It?”).

A graphic that shows hows how the presence of each Mexican cartel has changed during the presidency of Enrique Peña Nieto. The bigger the bar, the larger the number of states where that cartel operates. (The Juarez cartel in green, for example, is operating in less states in 2015, compared to 2012-2014.)

Animal Político has also been breaking new digital ground. With a newsroom in Mexico City and 20 staffers, over one million followers on Twitter, another million on Facebook, and two million unique visitors per month, it has become one of Mexico’s most popular and trusted news sites. Apart from launching Narcodata and a series about what it’s like to live with narco violence, the website experimented this year with live fact checking of Peña Nieto’s State of the Nation address.

Ramos has been instrumental in these initiatives. She was one of three reporters working at Animal Político when it launched in 2010, and was named executive editor in 2013. The site’s Director General, Daniel Moreno, encouraged her to focus on developing innovative digital projects. When Montalvo shared the document from the Attorney General’s Office with Animal Político’s editorial team in October 2014, Ramos saw an opportunity.

Around the same time, Chilean journalist Miguel Paz, who created Poderopedia, a platform that maps the most powerful people in politics and business in Chile, told Ramos about HackLabs, a new incubator for data-driven journalism in Latin America. Hacklabs was started by Argentinian journalist and Knight International Journalism Fellow Mariano Blejman, and is supported by organizations like the Knight Foundation, the World Bank Institute, and the International Center for Journalists. Paz had expanded Poderopedia to Colombia and Venezuela, and now wanted to partner with Ramos to map powerful business people in Mexico. But Ramos suggested something else: focusing on drugs and organized crime. HackLabs soon awarded Animal Politico a grant to create Narcodata.

Ramos and her staff at Animal Político decided to look back four decades, starting with to the 1970s, when drug trafficking organizations started to resemble the cartels we see today, with leaders and a robust organizational structure, Ramos says. They filed information requests for additional data on these cartels, but to get information dated before the early 2000s, when Mexico’s Law on Transparency and Access to Public Information took effect, they had to look elsewhere. The small team researched news archives, press releases, and books written by leading experts on organized crime like academic Luis Astorga, and Guillermo Valdes, a former head of Mexico’s intelligence agency. “The validation of experts was fundamental to us, so that no one could say: ‘No, that’s not true,’” Ramos explains. “We want [Narcodata] to be the outlet that presents information that has been verified, that is rigorous.”

They also received extensive advice from journalist Alejandro Hope, a security and justice editor for El Daily Post, an English-language news website that covers Mexico for an international audience. Among Hope’s contributions to Narcodata is a feature article (published in English at El Daily Post) with an interactive visualization that shows how drug cartels have moved from international drug trafficking to local extortion and kidnapping.

The initial funding Narcodata received through Hacklabs contemplated the eight longform, data-based articles that are currently posted on the website, but the team is already working on new features to keep the project going in 2016. Ramos says that Narcodata will last “as long as there’s organized crime in Mexico. If Mexico had effective strategies to fight drug trafficking, we wouldn’t have gone from two to six, to nine cartels. So I’ve always thought of Narcodata as a live and unfinished project.”

Future plans include an English-language version of the website and printable, poster-size versions of their visualizations for anyone who wants to post the history of Mexican organized crime on the physical wall of an office or classroom.

In a nation where rising violence against journalists impedes rigorous investigative reporting about organized crime, a project like Narcodata is especially relevant, says Meneses, the media researcher. Peña Nieto’s first year in office, 2013, was the most violent year for journalists since 2007, according to the human rights organization Article19, which reported that four Mexican journalists were murdered that year and the number of non-fatal attacks against them increased by nearly 60 percent. In the first six months of 2015, the same organization reported six murders and 227 attacks against the press in Mexico.

Because journalists working with data are less vulnerable to such violence than those reporting from the field, Narcodata is setting a good precedent, Meneses says. It’s showing Mexican journalists that new ways of covering crime in the country are not only possible, but necessary.

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.