Sign up for the daily CJR newsletter.

Just after noon eastern on Monday, the @Breaking News Twitter account, which has close to 1.7 million followers and is operated by MSNBC.com, tweeted that a “Large plume indicates second Icelandic volcano, Hekla, has begun erupting – watch live http://bit.ly/9iNfKE”

The shortened link led readers to a webcam operated by Iceland’s weather service that was labeled to suggest it was trained on Hekla. Within seconds of the @BreakingNews tweet, people began retweeting and spreading the news of a second Icelandic volcano eruption.

Alex Johnson, a project reporter for MSNBC.com, is the person who sent out the Hekla tweet. He works out of the Microsoft campus in Washington State, and one of his duties is to occasionally take a shift running the @BreakingNews Twitter account. On Monday, he watched as his tweet spread on Twitter, and he grew somewhat concerned.

“When people were staring to tweet it, they stripped it of all the hedging,” he says, referring to the fact that his initial tweet used the word “indicates.” As news spread and people began treating the report as definitive, which Johnson says was not his intention, he followed up with another tweet to emphasize that authorities had not confirmed an eruption at Hekla. In the end, it turned out that Hekla hadn’t erupted, so Johnson was faced with the challenge of issuing a correction on Twitter—something for which there are no established standards.

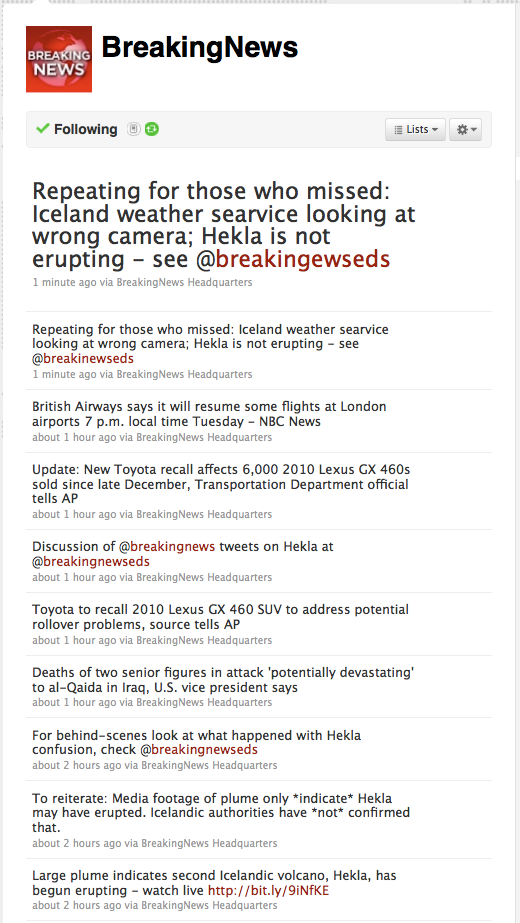

Interestingly, one thing he did was to direct people to another Twitter account, @BreakingNewsEds, which had been created to offer people a view into how the journalists running @BreakingNews make their decisions. The screen grab below shows a roughly two-hour progression of tweets on the main feed, from the first mention of Hekla to the point when Johnson began to direct people to the editors account and issue corrections:

It was a tough day for Johnson, but he also says making mistakes is part of being in the breaking tweets business.

“Like all breaking news Twitter sites, we’re doing a form of journalism that’s still being formed,” he says. “What is the right balance between speed and sourcing? Who do you attribute to?”

“The buzz word around here is that @BreakingNews is iterative journalism, so [we try to make sure] you can see the process, and if we screw up you will see the screw up, and we owe it to you to explain how and why that happened,” he says. “The more we let users and followers in on how that’s evolving, the better it is for us and for the entire form.”

One of the lessons of this episode is that backchannels, which allow journalists to share details of their reporting process and interact with readers, are especially valuable to this iterative approach. The use of the separate editors account suggests a model for thinking about how to correct an errant tweet, and deal with similar challenges on Twitter and elsewhere.

Some further suggestions are below; please add yours in the comments.

1. Provide a backchannel: As indicated above, it’s important to have a mechanism that can create a go-to place for readers, users, or other people who are trying to understand the how and why of something that went wrong. On Twitter, this could be done with a second account, or by using an existing one. They key is to explain things and respond to questions. Traditionally, newspapers used ombudsmen to fill this role: the ombud would write a column to explain things to readers, and get answers from those within the organization. This kind of delayed gratification won’t work in a breaking news context, or with the river of news. So think about creating an editors blog or a special Twitter account, or perhaps use a Facebook page to provide instant context and explanation and, perhaps most importantly, answer questions from people. Johnson used the @BreakingNewsEds account, which enabled him to keep the regular @BreakingNews account focused on news. (He also made sure to repeatedly direct people to the editors account.)

Keep in mind, though, that having a backchannel doesn’t guarantee that people will use it. For example, Craig Kanalley of Twitter Journalism and The Huffington Post chose to engage in a debate with Johnson by using Johnson’s personal account. So there’s another lesson here: people may not only use the backchannel you create. Be flexible and respond where needed.

2. On Twitter, one correction isn’t enough: Johnson tweeted several times about the Hekla situation, offering what was in effect multiple corrections (or pointers to corrections). Since Twitter messages flow by in a constant stream, it’s important to repeat your corrections. It’s difficult to say how many corrections are necessary, but one good way to gauge would be to see if the mistaken information is still being retweeted. As long as it’s being passed around, you should be issuing corrections and asking people to RT your correction. Remember that when something is retweeted, it takes on more authority among people and search engines—so your job in issuing a Twitter correction is to get it retweeted as much as possible. (Kanalley made this point during the Hekla story.)

3. Signal clearly: Johnson’s initial tweet about Hekla read, “Large plume indicates second Icelandic volcano, Hekla, has begun erupting…” For him, the use of “indicates” signaled the information not totally confirmed. But there are a lot of people who skipped over that word, or simply took it as an “indication” that a second volcano was erupting. A better way to hedge would be to begin a tweet with UNCONFIRMED or DEVELOPING or EARLY REPORT. The same goes for a correction: Put CORRECTION in all caps, or find another way of making the word stand out. You have to capture people’s attention as they’re watching all the other tweets stream by.

4. Annotate it: As I noted in last week’s column, I think Twitter and other new platforms have a role to play in creating features that enable corrections. At the very least, they can help popularize standards for indicating unconfirmed or corrected reports. Along these lines, this week ReadWriteWeb’s Marshall Kirkpatrick wrote an interesting post about the upcoming “Twitter Annotations” feature. Of course, I instantly thought that Annotations could be a great way to embed corrections or forms of hedging in a tweet. As Twitter rolls out Annotations, people should be thinking about how to make corrections a part of this framework. Though he doesn’t mention corrections, The New York Times programmer Jacob Harris wrote about some related uses on his personal blog. I’d love to see smart people like Kirkpatrick and Harris think about marrying Annotations and corrections.

Correction of the Week

A REPORT in The Weekend Australian on Saturday (“Deripaska’s hard stare has vision”, Page 25) made reference to Russian businessman Oleg Derispaska and links to organised crime. The Australian accepts it has no evidence whatsoever to support the allegation, it withdraws any implication to that effect and unreservedly apologises to Mr Derispaska for any harm he may have suffered as a result of the publication. — the Australian

Correction: An earlier version of this column misspelled Craig Kanalley’s last name as Kanally.

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.