Stanley Nelson is the editor of the weekly Concordia Sentinel, a 5,000-circulation newspaper in Ferriday, Louisiana. Nelson, head of a three-person newsroom, covers it all: the police, the courts, the drainage commission, politics, government, the rising this, the falling that, all of it playing out along the Mississippi River, sometimes in it, and sometimes across it, in Natchez, Mississippi. He writes a weekly column on the area’s history. His readers learn about local hero Jim Bowie’s famous sandbar fight in 1827, the tornado of 1840 that killed three hundred people, the cholera outbreak nine years later. Sometimes he writes about the area’s notorious past—gambling, prostitution, corruption, and the historic Klan-infestation of law enforcement. He also reports and writes about three unsolved civil rights murders that took place down his way, two in 1964, one in 1967. He is a member of the Civil Rights Cold Case Project, whose goal is to dig out and reveal the truth behind these murders. In January, he named a living suspect in the 1964 Klan murder of Frank Morris in Ferriday, which has led to a grand jury investigation. To some, Stanley might seem like just a slow-talking, easygoing good ol’ boy. He is, but that ain’t all. Even after plowing through thousands of documents, interviewing scores of people and writing more than 150 stories about murders that are more than four decades old, Stanley has an incredible memory for detail, the ability to follow the trail of complicated and shadowy whodunit theories, and unlimited passion for exploration and discovery. Last May, he was a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize in local reporting “for his courageous and determined efforts to unravel a long forgotten Ku Klux Klan murder during the Civil Rights era.” Hank Klibanoff interviewed Nelson in March.

A Moral Responsibility To Act

I was drawn to journalism in college because I loved writing. But when I started working for the Hanna family at their weekly newspapers in Louisiana, I found out pretty quickly that a lot more was expected of me. I had to take pictures and learn how to develop them in the darkroom. I’d answer the phones. I’d wait on customers at the front of the office, take their subscription money and give them a receipt. I’d sell ads if that needed to be done. Still, the early years offered me plenty of opportunities to focus on writing. How can you miss when you get a call about an old man who, thirty years after he carved the date and his initials into the shell of a terrapin, sees that same turtle crawling across his lawn again?

I came to see that while writing was fun, it was reporting that was the key to being a journalist. As a reporter, I was the eyes and ears of our readers. I covered a lot of criminal trials, dramatic ones, and it became clear readers were hungry for the coverage because we’d always sell out the newspaper. And if it weren’t for you, the reporter, they’d never know what’s going on. It requires you to get it right: the testimony, the cross examination, the meaning of it. You have to take good notes. I remember being accused by a school board member of having a tape recorder hidden in my pocket because he thought there was no way I could take notes that fast.

I am fortunate to have learned early that the key to reporting is having the willingness and sometimes the nerve to ask questions. But it’s more than that. As a journalist, I saw that I had a duty and responsibility to ask questions. I recall sitting in the Concordia Sentinel newsroom one day when the district attorney came in. He had been summoned by Sam Hanna Sr., the newspaper owner and editor, who asked me to join them.

Sam Hanna was a hard-nosed reporter and a great political writer. He loved everything about the newspaper business. He loved the sound and the feel of the presses rolling and humming. He smoked a cigar and was just an energetic force, a true newspaperman. He would type on his Underwood and it would sound like a machine gun. Whenever he’d be away on an assignment and needed to call in his story, he’d always ask for me to take dictation. He’d write it in his head as I was typing and it was perfect.

That day the DA came in, Mr. Hanna was unhappy. There was a lot of vice in the area, and a lot of tolerance of it from law enforcement. Mr. Hanna had heard about a new business in town that plainly had prostitution operating in the back in broad daylight. Mr. Hanna wanted to know why the DA hadn’t done anything about it. He wanted to know what he was going to do about it. He wanted to know when.

My eyes kind of bulged out because he was very bold about his questions and very firm in asking them. I think Mr. Hanna felt that once you knew about something that was wrong in the community, it would be morally irresponsible not to act on it. The lesson to me as a young reporter wasn’t that it was the district attorney’s duty to shut down houses of prostitution (though it was), but that it was the journalist’s job to ask why he hadn’t. I just remember thinking that if Mr. Hanna hadn’t asked those questions, who else around here would have?

Stirring Up Old Hatreds

One day in 2007, when the FBI released a list of unsolved civil rights cases, one of the Hanna owners walked through the newsroom and said there was a Ferriday case on the list. Even though I grew up not far from here, I had never heard anything about it. Of course we’re always wanting the local angle on a national story, so I began making some calls.

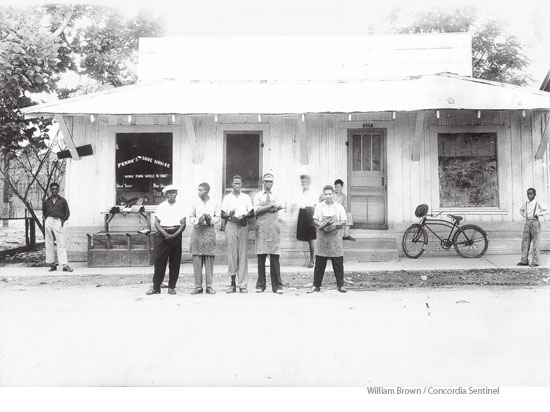

One call led to another and pretty soon I had some redacted FBI records gathered by the Southern Poverty Law Center. That, plus a story we had published in the paper in 1964, provided enough information to report that the FBI list included the 1964 arson of a shoe repair shop owned by Frank Morris, a black man, and that the FBI suspected it was race-related. Morris was inside when the fire was set. The fire consumed him and he ran from the building in flames. He was burned horribly and lingered in agonizing pain for four days before dying.

After my first story or two, the grand-daughter of Frank Morris, Rosa Morris Williams, called me from her home in Las Vegas. She had lived in Ferriday and was twelve when Morris’s shop was torched. She had vivid memories of a delightful grandfather with a great sense of humor, and of the fear black people had of the Klan.

I just kept going, kept reporting and writing, about Morris and two other blacks killed by the Klan, Wharlest Jackson and Joseph Edwards. I felt about their cases the way Mr. Hanna felt about the prostitution: it would be morally irresponsible not to learn more, write more, and see who was accountable.

Investigative reporting is not something I ever thought I would do. It’s not glamorous, especially when you’re one of three people trying to cover the community and put out a weekly full-service newspaper. When you’re looking into murders that took place forty and fifty years ago, you feel lucky just to learn whether the people mentioned in old documents are alive. Finding, reaching, and talking with them and others who may know about it is another challenge altogether.

The biggest hurdle is just finding out what happened. What precipitated the decision to kill Morris, Jackson, and Edwards, what planning took place? And how did the killers do it? This is one of those rare cases where the “why” of what they did—pure racial hatred—was easier to get than the “how.”

I realized right away I could not do this by myself. I got great help from two Syracuse University law professors, Janis McDonald and Paula Johnson, who learned about the case from me when they were down here on something else. They dove in and did great work gathering records and finding people. I joined other journalists like Jerry Mitchell, David Ridgen, John Fleming, and Ben Greenberg to create the Civil Rights Cold Case Project under the Center for Investigative Reporting; those guys shared tips, documents, and ideas. I have gotten great interns from the journalism programs at lsu, the University of North Carolina, and the University of Alabama.

When you do something like this, you have a choice on how to present it to readers: you can do months and months of research without printing a word until you’re finished, or you can do it the way I did it. I didn’t know if this thing would ever have a conclusion, or if I’d find anybody alive who knew anything, so I kind of educated readers as I educated myself. I took it week by week and reported what I learned that week so that it would open people’s eyes as it did mine and help jar memories and maybe compel people to come forward.

That’s what happened. I wrote stories based on documents I was accumulating, and on calls I was making to old law enforcement guys and to family and friends of Morris, Jackson, and Edwards. I started getting calls. Some people didn’t know anything about what happened in these murders, but told stories about the people involved, and gave me background and insights. A huge break came when Leland Boyd, after hearing about and reading my stories online, called me from Texas and started telling me about his daddy. I knew about Earcel Boyd Sr. and had records on his activity in the Klan and his role in the Silver Dollar Group, a violent Klan offshoot.

Then I spoke with Leland’s brother Sonny, who was a teenager during that time and who had clear memories of what he saw and knew. It was amazing how open they were, and they had lots of wonderful knowledge, much of it eyewitness information from Klan meetings and Sunday fish fries with other Klan families, when the men would test explosives on tree stumps. They revealed the challenges of life inside their home, where their chores as teenagers included hauling bombs and bomb-making materials up to their attic. There were things about their daddy they hated and things they loved, and they were able to talk about it all. They were like rolling the calendar back to that time.

If I had just built up research and hadn’t written anything for months at a time, Rosa Williams and Leland Boyd would not have picked up the phone to call me. Every article I wrote presented something new or clarified something. Doing it that way also put me in touch with my readers’ attitudes, both good and bad. The newspaper sold well every time I wrote those stories, and the website got busier. But I also encountered hostility. I’d have people tell me, “You’re stirring up these old hatreds,” or “Why’re you doing this?” and “I think it’s terrible you’re doing this.” I’m sure my owners, the Hannas, the widow and children of the late Sam Hanna Sr., heard the same thing, but they stood by me the whole way. They trusted me enough to let me go.

In a story that goes more than forty-five years back in time, you’re dealing with a lot of older people, so the trail led to nursing homes, people on respirators, others in various stages of Alzheimer’s. A couple of times it led to the door of people who had died just before I arrived. And it led to cemeteries. There was a particular gravesite I was looking for, and that pursuit led me into an area of reporting that was new and fascinating to me.

Joseph Edwards was a popular black employee at the Shamrock Motel in Vidalia. He did a little of everything. The Shamrock, naturally a white establishment, was where the Silver Dollar Group was started. There was a seedy element there, including a lot of white men running in and out of rooms occupied by single white women. Information in FBI records suggests one of Edwards’s responsibilities was to help procure men for the women, and he may himself have been with women there. One of the women lived at the Shamrock with her three-year old son. One day in June 1964, apparently when she was with a man in her room, she lost track of her son.

Looking for the boy, Edwards found him in the motel swimming pool, drowned or drowning, and jumped in to try to save him. Edwards himself then nearly drowned and was rescued by the boy’s mother. Two weeks later, Joseph Edwards disappeared, and hasn’t been found since. Edwards’s disappearance is still a sorrowful and mystifying loss for his family, especially his sister.

So I’ve been looking for the mother of the drowned boy to see if she knows anything about what happened to Edwards. I tried to find where her son was buried. An intern from the University of North Carolina, Tori Stilwell, spent a lot of time with me trying to find old cemetery registries. We found one and, sure enough, it led us to the boy’s gravesite and tombstone.

We found out that the woman, the mother, also had a daughter. Tori located the daughter and we called her. She was estranged from her mother, didn’t want to talk about her, and wasn’t interested in helping us find her.

Then we mentioned that we knew where her little brother was buried. There was a long pause on the phone. She had never known where he was buried, but had always wondered. She agreed to meet us at the cemetery. I felt like if I did that, she would open up. So we met there and just talked. After awhile, I showed her a picture of Joseph Edwards, then I showed her a picture of Joseph Edwards’s sister.

“Joseph Edwards tried to save your brother’s life,” I told her, “and may have been killed in some degree because he may have been around your mother at the time.” I told her that Joseph Edwards had a sister and that his sister had gone forty-six years not knowing what happened to Joe Ed. I think the parallels in their lives—two sisters trying to find some evidence of their brothers—was pretty amazing.

Well, she started crying. She had finally found the burial ground of her own brother and now she was in a position to help Joe Ed’s sister maybe learn something about what happened to her own brother.

So she told us where her mother was, and we have found her. We’ll have more on that later.

Who I Am

Working with the Civil Rights Cold Case Project has been a great help. They’re using all the current technological techniques to convey our stories—video, audio, Facebook, and other social media. That’s all pretty new to me. I know the value of video for a documentary, but having a camera rolling when I am going about my interviews can be a distraction, so I’ve had to draw the line.

Last year, all my calls to former law enforcement people about the Frank Morris murder finally yielded a man who said he knew something about the case. He said his former brother-in-law, a trucker from Rayville, Louisiana, had told him years ago that he participated in the arson that killed Frank Morris.

That led me to the Rayville trucker’s son, who said he had heard the same story from his father over the years. (He said his father always insisted that the plan was only to torch the building and that they had not known anyone would be inside.) Then I spoke to the trucker’s former wife, who said she, too, had heard that story from a longtime friend of hers who placed himself at the arson with her former husband, the truck driver.

When it came time to talk with the trucker, I wanted to do it the way I always do: walk up to the door with my notebook in my back pocket and my pen in my shirt pocket, and just explain who I am and try to talk with them. But for reasons I understand, my colleagues on the documentary side wanted to walk up to the house with me and have their cameras rolling as I knocked on the door and confronted the trucker with these claims by his family.

But I’d never done that before and I didn’t feel comfortable with it. I’d rather let people I want to interview see me as someone who wants to talk with them. I’m pretty quiet and pretty slow moving, and I just wanted to make sure I handled it the right way. I try to be non-threatening in my manner. I just want people to relax because I think they talk better that way. I know I do. That’s just kind of who I am.

So I went up there alone. My colleague, filmmaker David Paperny, got worried when he didn’t hear anything and came up a few minutes later with his camera running. The trucker seemed fine with it and signed his approval and we got good video. But the trucker was adamant later that he wouldn’t talk to me again. I think I can get just about anybody to talk with me a second time, so I can’t help but wonder if he’d have done it if there hadn’t been a camera filming that first time.

I understood from the beginning of the Frank Morris case that it would be a long shot to figure out what happened and who did it. But that’s just not a good reason to walk away from it. It would have been almost immoral to walk away from it. I mean, think about it, if we don’t do it, who would? If we don’t do it, it doesn’t get done.

Please note that the image for Stanley Nelson that appeared in the print version was wrong. A full correction will appear in the Letters section of CJR’s January/February issue.

Hank Klibanoff is the James M. Cox Professor of Journalism at Emory University. In 2007, he won the Pulitzer Prize for history for The Race Beat: The Press, the Civil Rights Struggle, and the Awakening of a Nation, which he co-authored with Gene Roberts.