Followers of Leroy Sievers’s “My Cancer” blog knew its expected end approached when Sievers published an entry titled “The Disease Has Exploded” in June 2008. It had been a slow detonation for the former Nightline executive producer and war correspondent. Sievers began writing the blog for NPR in 2006, shortly after the colon cancer he overcame in 2001 resurfaced in his lungs and brain. By the time the disease “exploded,” it had spread to his ribs, shoulder blades, liver, and fractured his brittle pelvic bone. Still, he continued to write nearly every day until his death three months later; his wife, journalist Laurie Singer, often typed as he dictated in their Potomac, Maryland home. Sievers’s last post, published the day before he died, was a brief note on the toy dog sitting with him in bed, his “comrade in cancer.”

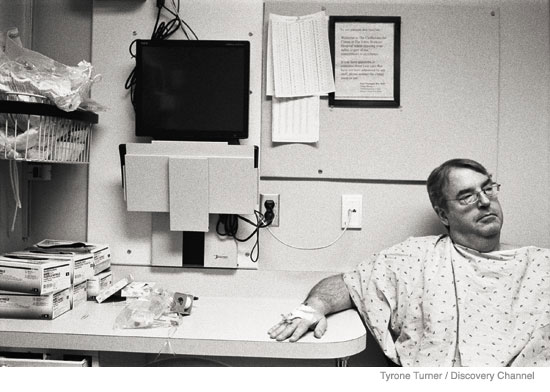

You might know the story. Sievers was an Emmy-winning producer before the cancer, and in the early 2000s became something of a poster boy for colonoscopies, writing frankly on Nightline’s daily e-mail newsletter about his first diagnosis. With the relapse, he became something of a sensation. A community of patients, families, and caregivers swelled around the NPR blog, and Sievers made multiple radio and TV appearances as his profile rose. Most famous of these was with Lance Armstrong and Elizabeth Edwards in his friend Ted Koppel’s hybrid town hall/documentary project for Discovery, Living With Cancer. Sievers would joke, “Getting cancer turned out to be a good career move for me.” He suffered and died publicly, and never stopped reporting as he did.

At a time when journalists increasingly turn their reporter’s eye inward, Sievers was not alone in reporting about his battle with disease. A number of journalists, facing damning diagnoses, have blogged about it until their deaths, or into remission. In the United Kingdom, former Huddersfield Times reporter Adrian Sudbury wrote about his fight with leukemia as the “Baldy Blogger” before dying at twenty-seven, just days after Sievers. Dana Jennings, assistant editor of The New York Times’s Arts and Leisure section, began writing for the paper’s “Well” blog after chemotherapy and a prostatectomy left him an incontinent “bazaar of scars.” Kairol Rosenthal was a modern dance choreographer before her diagnosis spurred her to become a journalist, reporting daily on life as a twenty- and thirty-something with thyroid cancer. Last year, not long after Christopher Hitchens had famously written about his cancer in Vanity Fair, NBC online reporter Mike Celizic wrote a final entry to his sporadically updated online “Cancer Journal” before he died in September. “The words are hiding somewhere,” he wrote. “But I’ve sworn to myself that I wasn’t going to write one entry and disappear. For once, I’ll get a story in without a deadline—no pun—to push me.”

Patient-bloggers like these are nothing new. Google “illness x” and “blog” and you will find a web crawling with amateur Leroy Sieverses; the Association of Cancer Resources Online has promoted a kind of blogging since 1995 with a slew of listservs categorized by cancer type. Patient-journalists are hardly news, either. Medical reporters still talk of the “Katie Couric effect”—the spike in colonoscopies following Couric’s on-air test in 2000—and before her, The Wall Street Journal’s Laura Landro went from covering Hollywood to writing a book about her leukemia based on a “Special Report” she wrote for the Journal in 1996, headlined a survivor’s tale. Former Bloomberg reporter Roger Madoff, who died at thirty-two, wrote a book about his own struggle with the disease called Leukemia for Chickens. The difference now is that as patient-bloggers, journalists bring their reporters’ chops; and as journalists, they bring a blogger’s intimate personal tone, constancy, and often, a band of followers keen to interact with the authors and each other.

Sievers’s “My Cancer” blog began on radio. When his cancer returned, he decided to focus one of his regular Morning Edition commentaries on his chemotherapy—it began, “My doctors are trying to kill me.” Impressed by his frankness, NPR suggested a blog (one of the outlet’s first) and a weekly podcast to go along with his broadcasts. Koppel, a close friend who spoke with Sievers daily until his death, had discussed the idea of creating a record of his experience just weeks after the cancer returned. “In Leroy, you had this extraordinary combination of a man with a wonderful sense of humor, writing skill, knowledge of the media, and a very strong man who was willing and able to undergo so many different procedures,” says Koppel. “He was uniquely placed to give a running account of what a cancer patient had to endure—the ups, the downs, what Leroy always referred to as the roller coaster.”

Sievers did not necessarily dig deep into the medical questions surrounding his treatments and prognoses. But he reported unflinchingly on his own condition, feelings, thoughts, and could fashion a helluva lede. In January 2007 he wrote:

I was sitting in the radiation waiting room yesterday morning. It was crowded. The computers had crashed earlier and everything was running way behind schedule. Everyone else there seemed to know one another; they had been getting the treatments for a while. I was the new guy, but was immediately welcomed into that instant community of cancer patients. Everyone there was older. At fifty-one, I was one of the younger patients.

And then one of the men said, “There’s a child in there.” The big, lead door had opened and he could see into the treatment room. Immediately, everything changed. The room got sort of quiet; people even lowered their voices. This was something terrible.

Joe Matazzoni, an executive producer at NPR who helped launch the blog, describes it as “a wonderful public performance of what is usually a private drama.”

“Leroy was a journalist and he brought that to his own experience with cancer,” he says. “The way he could write, in a manner that was so direct, without self-pity, and without mawkishness of any kind, and address the big issues of mortality, frankly spoke for itself.” It spoke to others, too. Sievers’s wife Singer recalls one man writing in after visiting his cancer-stricken father in the hospital. Asked how he felt, the father responded, “I don’t know, go read Leroy, he will tell you how I feel.”

Singer says her husband approached cancer as he had war. “He covered fifteen wars and his focus was less the war itself than the death and destruction of the conflict, the life lessons that could be drawn from it. That’s how he felt about the cancer. He wanted the reader to take away from what he was going through whatever they could learn about life more than death.” In a Morning Edition commentary from November 2006, transcribed for the blog, Sievers said:

A doctor told me early on that cancer meant many people would want to talk about things I definitely didn’t want to talk about. He was right. I have to talk about my body to strangers. I have to talk to my doctors about my greatest fears. I have to talk about my death. But it doesn’t bother me anymore.

I don’t worry as much about keeping up a facade, either. I have cried, more than I ever had before. I’ve been more open to friends and loved ones about how much they mean to me. Before I got sick, I would’ve been embarrassed to say some of those things out loud.

In the cancer wards, you see more physical displays of affection. A touch, a hand on the shoulder, some gesture meant to reassure or just let the other person know they’re not alone. Cancer teaches that worrying what other people will think and being discreet is something we don’t have time for.

What has happened, I think, is that we’ve all been humbled. Cancer has freed us to do the things we knew we should be doing all along.

The Times’s Dana Jennings’s decision to write about his own long, cancerous brush with death came just as organically. Test results after his July 2008 prostatectomy revealed a cancer more aggressive than doctors originally thought. Struggling for a new book idea, he needed to push past the wall this diagnosis erected in his mind. Jennings enacted a professor’s advice from college—write through what’s blocking you—and, from November until the following October (and intermittently since then), detailed his life with cancer and the effects of the treatment on his body in weekly updates of uploaded videos and blunt, unsentimental prose on the Times’s “Well” blog.

He was filling a need he found after his own diagnosis, when he was unsatisfied with widely available, but dry and often technical, online writing on cancer. “I was really looking for a strong, compassionate voice,” he says. “I wanted to read something where I felt like another human being was talking to me. Another human being who could write well.”

His own body was his number one subject. “Almost all of the side effects are just really difficult,” he says. “Guys don’t want to talk about incontinence and impotence, your penis shrinking. But that stuff happens. I wanted to be honest.” Jennings managed to mix humor with honesty, writing in one post: “I’m not quite what you’d call a catch. I wear man-pads for intermittent incontinence . . . and haven’t had a full erection in seven months.”

In June 2009, he wrote of the side effects of hormone therapy:

When I wasn’t devouring a king-size Italian sub or smoldering from a hot flash, it seemed that I was crying. The tears would usually pour down when I got ambushed by some old tune: “Sweet Baby James” and “Fire and Rain” by James Taylor, “That’s the Way I’ve Always Heard It Should Be” by Carly Simon and, yes, “It’s My Party” by Lesley Gore. Not only was I temporarily menopausal, but it appeared that I was also turning into a teenage girl from the early 1970s.

Like Jennings, Landro says an urge to honesty drove her to write about her disease for the Journal in the 1990s—to show readers what the doctors won’t tell them: “They’re not going to tell you that you’re going to throw up every five minutes for the whole two weeks ahead of you…. They’re not going to say that your esophagus lining is going to slide into your stomach, and it’s going to feel like fire when you swallow.” More than that, Landro wanted to show readers how she used her “ability to source, to interview, and to evaluate information”—her journalist’s toolbox—to navigate the health care system and to vet, in a very practical sense, everything she was being told. Cancer was like a foreign country; Landro wanted to provide a guidebook.

In her original WSJ piece, Landro reported that a suggested T-cell-stripping procedure was less effective than she’d been led to believe. “We learned about this not from either my hematologist or Sloan-Kettering, but by analyzing the hospital’s reports of its results in medical journals and comparing them to reports from other institutions,” she wrote, adding that once confronted, her “young doctor at Sloan-Kettering acknowledged that our analysis was essentially correct.”

Though such investigative nuggets are rarer in the new crop of cancer blogs, readers seem to appreciate their honesty and thoughtfulness. After his first post attracted over 200 comments, Jennings said to his wife, Deb, “I feel like I’m the Beatles of prostate cancer.” His most popular post, about the health problems of the family dog, Bijou, has attracted over 700 comments to date and spawned a book. “My Brief Life as a Woman,” Jennings’s entry about his months “aboard the Good Ship Menopause” as he underwent hormone therapy, was the Times’s most e-mailed story that day. Deb has been in touch with six wives of prostate cancer patients who read Jennings’s blog. She, and their son Owen, who survived non-cancerous liver failure in his senior year of high school, contributed to and were featured in the blog.

During its run, Sievers’s “My Cancer” was NPR’s most popular blog. Singer, his wife, remembers fellow infusion room patients telling Sievers, “I was feeling that very thing that very day you wrote it.” She recalls, “Leroy would say, ‘It’s almost a little scary for me. Should I be guiding these people through their journey with cancer?’ ” The “My Cancer” community grew so large and so loyal that Singer continued to write about cancer, her time as a caregiver, and grief, after Sievers died. The blog became NPR’s “Our Cancer” page in 2009 and will soon be hosted by Johns Hopkins cancer center, where Singer serves on an advisory panel.

New York Times “Well” blog editor Tara Parker-Pope, who published Jennings’s work, says the web has changed the nature of first-person health reporting, not only creating a daily storyline for readers to follow—not unlike a TV serial—but promoting interaction with the author and among readers in comment sections. A Jennings post about bad news is moving; it becomes intimate when you can offer an immediate note of consolation—and see it responded to just as quickly. And that can serve the storytelling. “What I love about the blog is that people take your story so much beyond the original story,” says Parker-Pope. Reader comments, Parker-Pope adds, can air the experiences of hundreds of readers as a print story never could.

On Sievers’s “My Cancer,” for instance, stories that emerged in the comments were brought into the blog. Stephanie Dornbrook, who kept her own cancer blog, “For Crying Out Loud,” was a regular commenter who earned a following among other “My Cancer” commenters and was featured in Koppel’s Living With Cancer project. Sievers included updates on her condition in his posts when her comments grew scarce, finally announcing her death in January 2008. Afterwards, Sievers posted a letter from Stephanie’s husband, Dustin Dornbrook. It read: “I know she cherished this blog site and all of you were loved by her. I am grateful to Leroy for making it available. It makes me happy so many of you will keep her alive through your memories.”

Despite the comfort the blogs have provided some, there are those who see potential concerns. “Personal stories and anecdotes are incredibly powerful,” says Dr. Andrew Holtz, an author and medical reporter formerly with CNN’s health unit. “The hazard is if the personal stories…are not representative of what the medical evidence says.” In regular medical reporting, anecdotes are chosen to accompany the evidence, or a new development, or the typical experience. These blogs, Holtz says, instead illustrate the old adage that “news is whatever happens to journalists.”

Holtz points to prostate cancer as a good example of where a personal blog might not reflect the medical evidence. New studies suggest that nearly all of the 200,000 cases of prostate cancer diagnosed in the United States each year are overtreated, with doctors mostly recommending the same radical prostatectomy that surgeons performed on Jennings.

A blog like Jennings’s in an outlet like the Times—showing a man who was seemingly saved by prostatectomy—could play against this latest evidence.

Jennings was aware of the concern: “I wanted to make it clear that anything said in the posts was simply based on my own experience—I didn’t want to come off as an expert except on my own case.” He grappled with how he was presenting his case after learning about the rash of supposedly unnecessary prostatectomies, asking if his ride “through the stations of the prostate cancer cross” had been “all a lie? A dark conspiracy of the global medical-industrial complex?”

I’m a wild card, the 1 man in 48 saved by surgery. Without it, my doctors wouldn’t have learned the cancer was so advanced, and wouldn’t have given me the hormones and radiation that helped keep me alive.

…But all of this raises one last stark question: Was my life worth the 47 other prostatectomies that probably didn’t have to be performed? I don’t know. I’m a man, not a statistic.”

That question of identity seems to be a fixation of all the writers. Would writing about cancer, becoming the face and voice of a diagnosis, forever change how they were perceived as journalists? Laura Landro knew she would be always be “that sick girl” after she wrote her WSJ report, but went ahead anyway to show that people could survive, and to show them how. Her cancer has relapsed three times and she is considering a follow-up to her book Survivor.

Jennings, on the other hand, with last year’s release of What a Difference a Dog Makes: Big Lessons on Life, Love and Healing From a Small Pooch, and his cancer in remission, looks forward to moving on. “I don’t want to be a professional cancer patient,” he says.

Sievers also had some thoughts on the matter, too. Realizing the comfort and companionship he gave readers, he once told Matazzoni, the NPR producer, that “My Cancer” was the most meaningful project of his career. Koppel saw it, too. Though Sievers’s spirits remained high during most of their calls—he jokingly questioned the wisdom of starting the seven-volume Harry Potter series—he didn’t always feel like writing. “There were many times when I think he did that blog only because he knew there were people counting on him,” says Koppel. “The reaction of readers was so touching and overwhelming that he thought it to be one of the major responsibilities of his life.” But in June 2006, two years before his disease overtook him, and before he would come to see the impact his blog would have, he issued a journalist’s call of defiance:

In the end, I may very well be best remembered as a cancer victim. That’s strange to me. I don’t think I like it very much. The cancer has changed just about everything. My life, my career, my body. But aside from that, I am still, at the core, the same person I was before. Maybe a little wiser, but the same person.

And so I guess this is the time to say something that I sometimes feel like shouting out loud. I hope I speak for all of you out there who have this disease when I say, “I am not my disease.” We, all of us, are much much more than that.

Joel Meares is a former CJR assistant editor.