If the digital revolution has done nothing else, it has exposed the extent to which American newspapers have relied on their quasi-monopolistic control over local advertising markets to fund news operations.

CW Anderson, Emily Bell, and Clay Shirky, in their valuable report last year, called it a “subsidy,” and that’s a provocative way to put it.

Here are the report’s five core points, all worth pondering (emphasis in the original):

Journalism matters.

Journalism has always been subsidized.

The Internet wrecks the advertising subsidy.

Restructuring is therefore a forced move.

There are many opportunity for doing good work in new ways.

Whether you buy the concept of subsidy or not, and I’m not sure I do entirely (more on this in another post), it’s painfully clear by now that there’s something to it. Much of the ad revenue flowing to newspapers in years past had nothing whatever to do with the news, and the same is true with the money flowing away lately. Some journalists (like me) find this hard to accept, but the numbers don’t lie.

Now, as everyone recognizes, newspapers don’t have a lock on the local car dealer, grocery store, and regular Joe with a parakeet for sale who needed to reach the local market.

So, the subsidy is going away, if it’s not gone already, and increasingly news operations are required to pay their own way. This isn’t about paywalls necessarily. But somehow, some way, they’ve got to find a way to earn the attention and trust of enough readers to make the cash register ring, either through clicks, subscriptions, conferences, memberships, or something else.

At this point, it’s pretty much about the news.

And that’s why defunding the newsroom now is patently the wrong strategy any way you slice it. And if it has to be done—and of course sometimes it does—it should be the very, very last resort. Literally, as a news organization, what else now do you have to sell?

I’m a contributor for a local news site in Providence called GoLocalProv. Last week, I wrote about the slow-motion train wreck that is the Providence Journal, my old paper, where in the last year or so, the paper’s parent, AH Belo Corp., has been extracting $1.2 million in concessions from unionized and other employees, resulting in demands for 53 job cuts from the editorial and sales sides. John Hill, president of the local Guild, says membership is off more than two-thirds from a peak of more than 500 to about 160 or less now. The figure includes both editorial and advertising personnel, typically about 60 percent editorial. This is beyond fat, and well into bone. Really, we may already be getting past the point of no return.

The paper, as I wrote, used to have nine—count them, nine—local bureaus (updating to add “local”; not counting the statehouse) covering that tiny state. I used to work in the Pawtucket bureau, all of five miles from the Journal newsroom. A fast bicyclist makes the trip in 15 minutes.

Today the number of Journal bureaus is exactly zero. As I said, the point isn’t that there should be nine bureaus, or any bureaus. The point is that the Journal‘s omnipresence—every Rhode Islander over 6 years old was probably interviewed by the Projo at some point—created the kind of intimacy that, we are learning today, creates real value. Loved and hated, often by the same people, the Projo was the hub of the community. True, it wasn’t interactive or even particularly responsive, and that’s not good. But that emotional and intellectual connection, which was taken for granted at the time, is what the Journal now has for sale. That, and little else.

That’s why now is not the time for executive bonuses, which Belo has given out to the tune of $3.3 million since 2011, according to reports by WPRI’s Ted Nesi.

Executive compensation is an opaque area, deliberately so, believe me. Aficionados can do their own arithmetic by downloading the company latest proxy filing

here. By my reckoning, the estimate is conservative, if long-term stock awards and other perks are included.

In a proxy statement, the company justifies the bonuses this way:

The newspaper industry continues to experience substantial change caused by the effect of the Internet and other transformational technologies on consumers and advertisers and the rapid ascent of new media businesses. From an executive compensation perspective, this business environment underscores the importance of attracting and retaining both experienced and high-potential executives, and rewarding superior individual performance that may not presently be reflected in the Company’s stock price, revenues or operating profit.

But granting executive bonuses—while cutting product quality—is exactly the wrong response to “substantial change caused by the effect of the Internet and other transformational technologies.”

Cutting the news staff, especially at this point, is not about trimming expenses. It is a form of disinvestment, of giving up on the future. This is especially disastrous at a time when the paper, very late in the game, is asking people to pay for online news via a paywall. Just when investment in the product is at a low ebb, you ask people to reach for their credit card.

We’ve seen this movie before. Newspaper companies in dire need of reinvestment, or at least to maintain current levels of product quality, instead divert resources everywhere else. At Dow Jones, excessive dividends to the controlling Bancroft family proved fatal, leaving the paper a sitting duck for Murdoch. The Washington Post Co. splurged on dividends and stock buybacks for years, then raised the white flag. Advance Publications is a story in itself, but it has the distinction of deliberately moving to a digitally focused model that made gutting newsrooms in New Orleans, Cleveland, and elsewhere, an essential part of its strategy. Read Ryan Chittum for the details there.

Even the Sulzbergers are guilty of golden parachutes and excessive dividends. As Chittum asks: “Does the New York Times Company have $24 million to spare?”

But in its defense, TimesCo. management has, much more than most, protected the newsroom, and now, not at all coincidentally, they’re making a go of it, and betting the entire company on a newsroom-centric model.

It is true that Belo manages two other papers besides, the Journal, including its flagship, The Dallas Morning-News. It is also true that Belo in 2012 swung to a small profit after years of disastrous losses due to writedowns of the value of the business, a big pension expense, and the general deterioration of the newspaper business.

The current year has been a mixed bag at best. A paywall at the Dallas Morning News was not well done, as Ryan reports this morning (UPDATE: adding link).

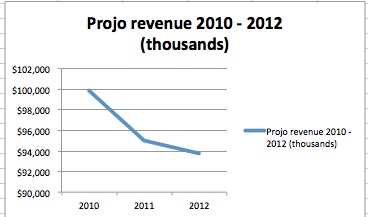

And all properties are experiencing sharp revenue declines, and in Providence, the situation is dire.

Here is what happened to revenue at the Projo in the last three years:

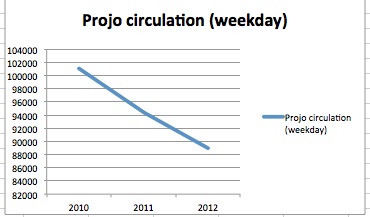

And here is what happened to circulation:

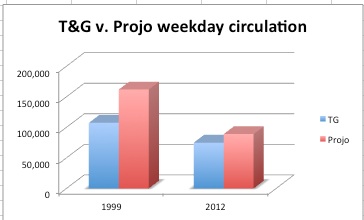

What’s more, as I noted, both metrics have fallen far faster than national averages. Circulation is the real stunner. Newspaper circulation nationally is off 20 percent since 1999. The ProJo’s meanwhile is off 45 percent, from about 165,000 to 89,000.

And as I noted in the other post, Rhode Island’s economy is worse than average, but the economy of Worcester—all of 40 miles away—isn’t that much better, and yet the Projo has lost circulation at a far faster rate than the Telegram & Gazette, which is off “only” 30 percent and is now not so much smaller than the Projo.

Point: This is not, repeat, not, the time for bonuses, for anyone, executives, reporters, or anyone else.

Every nickel diverted from the product at this point is a waste of resources. Yes, the company is going to have to come up with a plan to combat falling revenues. Either that, or sell to someone who is willing to try.

But step one: Stop eating the seed corn—and start planting it.

Dean Starkman Dean Starkman runs The Audit, CJR’s business section, and is the author of The Watchdog That Didn’t Bark: The Financial Crisis and the Disappearance of Investigative Journalism (Columbia University Press, January 2014). Follow Dean on Twitter: @deanstarkman.