Sign up for the daily CJR newsletter.

Hungarian press freedoms have been under pressure for a while as the right-of-center government has come under fire for ham-fisted meddling at the main public television station, abruptly canceling the license of the country’s leading opposition-leaning radio station, and other moves that have cast what human rights groups characterize as a pall of self-censorship over the country’s few remaining independent news organizations.

But what had been a tense standoff burst into open confrontation last week after the government imposed what critics say is punitive and politically targeted tax on media advertising, while the top editor of a leading independent website was ousted after the site published a series of scathing exposes documenting the lavish spending of a rising star in the ruling party of Prime Minister Victor Orban. Adding to the turmoil, government agents raided the offices of three non-governmental organizations that administer funding to civic and human rights organizations, as well as some independent news organizations.

In response, the media—and, to a surprising degree, public—are pushing back, in what observers here say is an unprecedented series of protests, including a 15-minute “blackout” organized by dozens of Hungary’s privately owned media outlets.

The press turmoil in Hungary illustrates some of the difficulties independent news outlets are having in maintaining a foothold in central and eastern European countries where governments, through their regulatory power, financial clout as an advertiser, and other means exert vast influence over the media landscape. As it happens, the media outlets at the center of the disputes last week are owned by German concerns, putting media companies in the middle of diplomatic tensions over what critics say is Hungary’s anti-democratic drift.

The week of turmoil in Hungarian media began Monday when a news site, 444.hu, reported that the top editor of an other independent site, Origo.hu, had been fired because of pressure brought to bear on management by the governing party, Fidesz.

The ousting of the editor, Gergo Saling, came in the wake of Origo’s publication of a widely acclaimed exposé showing that János Lázár, Orban’s under secretary in the office of the prime minister and an incoming minister to the new government, had racked up lavish expenses on business trips abroad during the government’s previous term. The story, which generated a frenzy on social media, stemmed from a successful freedom of information lawsuit for the expense reports after Lázár’s office had blocked access.

On Tuesday, Origo’s owner, Origo Zrt., issued a statement saying that Saling had stepped down by “mutual consent.” Origo Zrt. is a unit of a major telecommunications company here, Magyar Telekom, which in turn is majority-owned by German telecom giant Deutsche Telekom AG (which is turn is partly owned by the German government).

Soon afterwards, a leading investigative site, Altatszo.hu (“Transparent”), then published a leaked voice recording from a meeting at Origo’s offices during which staffers angrily confront the company’s chief executive officer as he insists that Saling had left by mutual consent.

Tuesday night, in an usual and somewhat spontaneous display of public support for the press, more than 1,000 people marched in protest in at a Budapest rally for the Origo editor. By midweek, at least 10 Origo staff members had resigned, including András Pethő, a well-known investigative reporter and author of the expense stories.

444 then published another story linking the sacking of Saling to efforts by Magyar Telekom to curry favor with the government as part of its pursuit of a big government contract and regulatory approvals, touching off a mini storm on social media. Hundreds of users posted links or comments to the 444 story on Deutsche Telekom’s and Magyar Telkom’s Facebook pages. In response, Deutsche Telekom issued a statement denying any involvement in the firing of the editor, calling the allegation “absurd.”

Meanwhile, the ad tax, which had been floated by Orban and his Fidesz party earlier this year, gained new impetus after the Orban’s reelection in April, and this week was formally introduced in parliament.

RTL Klub, owned by German publishing giant Bertelsmann AG, complained publicly and bitterly about the tax. In a statement to The Wall Street Journal, RTL Hungary and its parent, RTL Group, said: “In our opinion the objective of the introduction of this tax is nothing less than an aggressive attempt by the government to undermine the biggest media company of the country, which has proved its independence from the political parties and the government over the past 17 years.”

RTL Klub said it would end up paying about half of the estimated $31 million collected under the new tax.

The media blackout, which included most privately owned news organizations, was considered to be unprecedented here and was particularly notable because it included outlets that are generally regarded as aligned with the Fidesz government.

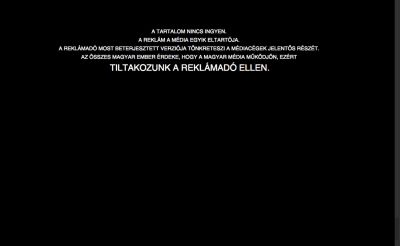

As part of the protest, TV stations and websites ran this black image:

The message reads:

Content is not free. Ads are one of the means to finance media The ad tax, as proposed, will undermine a significant number of media companies. Functioning Hungarian media is in the interest of every Hungarian. That’s why WE OBJECT TO THE AD TAX.

Almost lost amid the media mayhem was a raid by the government last week on the offices of three non-government organizations that help distribute the so-called European Economic Area and Norway Grants, funded by Norway, Iceland, and Liechtenstein aimed at reducing economic and social disparities with 16 central and southern Europe countries. The NGOs fund, among other things, independent media here but also an array of other civil liberties, human rights, and anti-corruption groups. The government accused the NGOs of political meddling, a charge the NGOs deny.

The raids were denounced by human rights groups, including Transparency International, which called them part of a “strategy of intimidation aimed at stifling the voice of civil society and democratic oversight.”

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.