The eyes of the nation have been on South Carolina over the last few weeks, after nine parishioners were murdered in a historic black church in Charleston. Three weeks later, on July 10, the Confederate flag was removed from the grounds of the capitol building. By the end of the day, the only remnant of the flag was a round scar in the concrete where the flagpole had stood. Sean Rayford, a local photographer, snapped a picture of it with his phone and uploaded it to Instagram.

“That’s me leaving the scene, and being done for the day,” Rayford said. He had already packed away his Nikon D610 and his other equipment, but he wanted to know what had happened with the flagpole. “I was curious myself. It was simply me being, ‘Here’s the scenario,’ for everyone who’s wondering.”

Rayford had been there all day, and the days before, at the Emanuel AME Church, at the 15-hour legislative debate that decided the fate of the flag, at the memorials and funerals and vigils for the nine victims, at the rallies for and against the flag’s removal, with his camera. His photos were on many major news sites including The Washington Post and The New York Times. The day after the state’s decision to remove the flag, his photo was on the front page of six daily papers, including The Philadelphia Inquirer, The Charlotte Observer, and the Detroit Free Press.

Rayford, with wild hair and a camera always at hand, is both noticeable and ubiquitous in Columbia, where’s he’s lived for over 15 years. He’s freelanced for the Free Times, Columbia’s alt-weekly, and for the daily paper, The State; he’s also bartended at the New Brookland Tavern, a fixture in the local music scene. He’s photographed bands, Gamecock fans, local athletes, frat boys, and politicians, capturing them in moments of anguish or ecstasy, mid-finger wag, howl of victory, or goofy grin. He’s photographed over 1,000 bands at New Brookland, he estimates. “I have a shelf of broken cameras, that I’ve broken,” he said, mostly from overuse.

“He always has his camera,” said David Adedokun, a local musician, “But he’s always there, so you stop noticing.”

Rayford had always taken photography seriously, but in 2014 he quit bartending and began focusing on photography full time. He began working with The State again after a long absence, committed to more advertising gigs, and began paying more attention to his blog.

On a Thursday three weeks ago—the morning after the murders—Rayford had just returned from a run when he got a call from Getty Images. “The guy on the phone is like, ‘Hey, my name is blah, are you interested in working with us?’ ” That’s a call every freelance photographer wants to get.

For his first assignment with Getty, Rayford went to the state Senate, which was meeting for the first time without Clementa Pinckney, the senator and minister who had been killed the night before at the church. A vase of flowers marked his spot in the assembly room.

“It was very emotional,” Rayford said. His photographs show senators wiping their eyes or holding back tears.

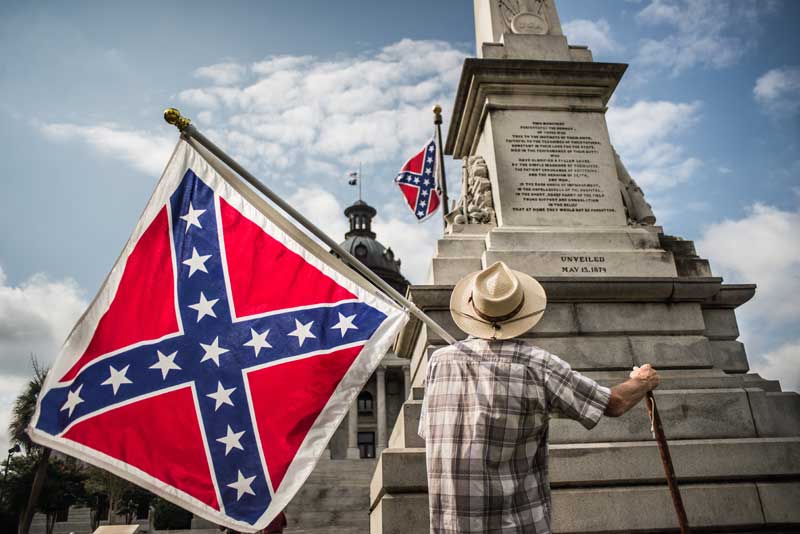

When he went to photograph the flag at half-mast outside the capitol, he noticed that he could frame it with the Confederate flag in the forefront and the dome of the capitol building in the background. “I’d run and walked past that flag a thousand times,” he said. That image is now all over the internet.

Covering Charleston was intense, said Rayford, but after the victims were buried, and the focus shifted to Columbia, “there was a mood of being on a mission.”

Photo courtesy of Sean Rayford

On July 8, while the South Carolina House of Representatives debated for 15 hours on a bill to remove the flag, Rayford wandered the capitol grounds photographing what he could. They were only allowing local media into the chambers, and as the debate raged on, Rayford listened via earbuds so he would know when to catch the representatives as they emerged. Even though he’s lived in Columbia since college, he didn’t count as “local media” because he was working for a national photo agency.

By evening, as the debate continued, the media congregated in the lobby trying to pass the time. Rayford, rumpled and bush-haired, started taking selfies with all the portraits of historical figures gracing the walls of the capitol building.

“I like to sit down when I take photos,” Rayford said. “You claim your spot, stake your shot. I know what shot I want, now I just have to wait for it to happen.” It’s more comfortable for him then getting right up close to someone in an emotional moment.

One of his early lessons as a photographer came when he interned at The State back in 2002-2003. “This was before newspapers tanked,” Rayford said, and The State had 10 or 12 staff photographers then, as opposed to the three who now work there. “People actually spoke to each other then.” After one of his first shoots, of a volleyball practice, his photos were out on the table where the staff would review the week’s images. A veteran photographer told him the photos were good, but that he wanted to see some emotion on the girl’s face. “It may not happen,” the photographer said, “But always be ready for it.”

“It’s something I’m always looking out for,” said Rayford.

“Sean has a desire to capture humanity, in all its perfections and imperfections,” said Kyle Peterson, a music writer in Columbia. For a feature on Five Points, a college hangout, Rayford spent a full 24 hours there, so he’d catch the authentic story. Last year, he self-published a book on the University of South Carolina’s Gamecocks fans, and this year he turned his attention to their bitter rivals at Clemson University. Rayford said he spent the fall trying to catch a Clemson fan vomiting. “No, really,” he laughed.

Shooting for Getty has allowed him to work more as he does when pursuing these independent projects. “With Getty there’s a lot more freedom. I have a longer time and they rely on me to tell the narrative story,” Rayford said. “With the dailies they’re looking for a specific shot.”

When Rayford’s shots for Getty starting getting picked up by national newspapers and magazines, his Instagram, Twitter, and Facebook pages filled with congratulations.

“It’s all over Facebook lately,” said Chris Bickel, a well-known Columbia musician and friend. “It’s really cool to see a national news story and to recognize the photographer. It’s like ‘That’s a Sean Rayford there.’”

Adedokun wasn’t surprised that with South Carolina on the national stage, it was Sean Rayford who was there to document it. “If the world chose to see this week’s events through Sean’s lens, the world picked well,” he said.

Rayford said he was looking forward to a week to rest—or go back to his regular schedule—but on Saturday, July18, there’s a Ku Klux Klan rally scheduled in Columbia. He intends to be there with his camera, with or without an assignment.

Chava Gourarie is a freelance writer based in New York and a former CJR Delacorte Fellow. Follow her on Twitter at @ChavaRisa