Sign up for the daily CJR newsletter.

The relationship between news organizations and platform companies has become far closer far more quickly than anyone predicted. The increasing influence of a handful of West Coast companies is shaping every aspect of news production, distribution, and monetization.

In the past 18 months, companies including Facebook, Apple, Twitter, Snapchat, and Google have moved from having an arm’s length relationship with journalism to being dominant forces in the news ecosystem. By encouraging news publishers to post directly onto new channels, such as Facebook Instant Articles and Snapchat Discover, tech companies are now actively involved in every aspect of journalism.

At the Tow Center for Digital Journalism at Columbia Journalism School, we have conducted the first research aimed at evaluating how newsrooms are adapting to the rising influence of technology companies. We found that some platforms are becoming publishers, either by design or by default.

Publishers, meanwhile, are experiencing a more rapid than expected shift in distribution towards platforms. In the research, newsroom personnel at every level expressed anxiety about loss of control over the destination of stories, the power of their brand, and their outlets’ relationship with the viewer or reader.

Many acknowledged that technology companies are, for some newsrooms, a potential lifeline. Individuals within news organizations felt they lacked the resources or expertise to create the level of innovation and access to new audiences that social media and platform companies offer.

But there are critical issues of democratic and civic concern that have little visibility or priority, either within news organizations or platforms.

We found that:

- Publishers are posting an ever-increasing volume of stories directly to many different platforms, but with little insight as yet into what the long term effects might be.

- Some platforms and publishers have a very close relationship, with some platforms providing equipment or financial incentives to publishers that use their tools. At least one platform even requires publishers to pay it a percentage of ad revenue in exchange for using the platform.

- Scale matters. Some smaller and local newsrooms feel left out, whilst the larger or “more digital” publishers that have the closest relationships with platforms dominate attention.

- Publishers’ anxieties include a lack of data, loss of control, the uncertainty of financial return, and the potential obscurity of their brand in a distributed environment.

- The question of who owns the user highlights the biggest tension at the heart of the relationship between publishers and platforms. Is a reader of The New York Times on Facebook a New York Times reader, or a Facebook user reading the New York Times?

- Civic and democratic issues not prioritised by either publishers or platforms include archiving distributed journalism, transparency in algorithmic distribution, concentration of power, and availability of data.

We spoke to more than 60 people who work in news organizations and platform companies, the majority through interviews, and a group of 15 social media managers through a round table held at Columbia Journalism School. Interviewees and roundtable participants were all directly involved in social distribution of news. We also conducted a week-long quantitative analysis of how publishers posted links or full articles across different platforms.

Some of the sentiments we heard from newsrooms and the patterns of adoption are very reminiscent of arguments first aired over the shift from print to the Web, but this time with far greater existential urgency. Social media and distributed content strategies are now seen as central to editorial decision making for the most digital newsrooms. A social strategy is now often a proxy for a mobile strategy.

At one end of the spectrum, the demands of the new ecosystem feel like a forced march. “To be honest, what we are experiencing right now is close to chaos,” a newsroom social media manager told us. “We have thrown so many new things at the organization in the last few years. This is just another new set of instructions.”

In other places, though, newsrooms both enjoyed new creative opportunities and the results they saw from the spread of their journalism. “Platforms have given us way more creative freedom than we have had in the past to tell a story,” one journalist told us.

Even at the local level, where the economics of Web scale have hit hardest, the possibility of using new infrastructure owned by Facebook or Google was alluring for some. “Our very small local sites will close, but they will retain their social presence,” said one local news publisher. “So we completely drank the Facebook Kool-Aid.”

Others were far more cynical about the drivers of competition in the mobile news world. “We are collateral damage in the war between platforms,” a manager at a local publication told us. “They’re fighting with each other…They will promise certain things to some, they’ll give [a publisher] a chance to play, but not to others.”

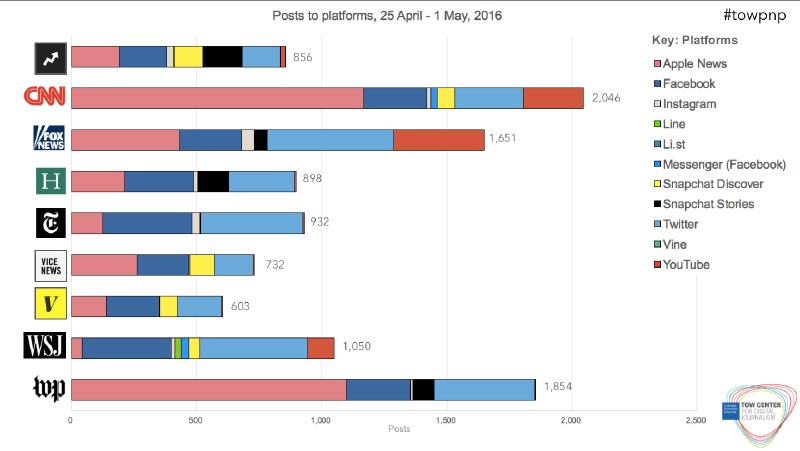

We gathered a range of experiences from isolated local newsrooms, where one interviewee admitted to still struggling with print deadlines and the decline of traditional publishing, to large legacy newsrooms that are aggressively embracing platforms. The latter group included CNN, which posts well over 2,000 pieces to third party platforms each week, and digital natives like BuzzFeed and Vox.com.

The sense that the future of news is now in the hands of the technology industry was much more prevalent among those who were least able to access the resources of platform companies. The head of digital at one local news publisher was adamant that the bias within platforms was “effectively picking winners” among the publishers. Others were less sure. “What you have to remember about even Facebook is that it is really still run like a startup, and whilst their actions might unintentionally favour certain players, the reality is that it is much too chaotic in there for that to be the case,” the publisher of a digitally native publication told us.

This grid shows nine diverse journalism companies posting across 21 different platforms.

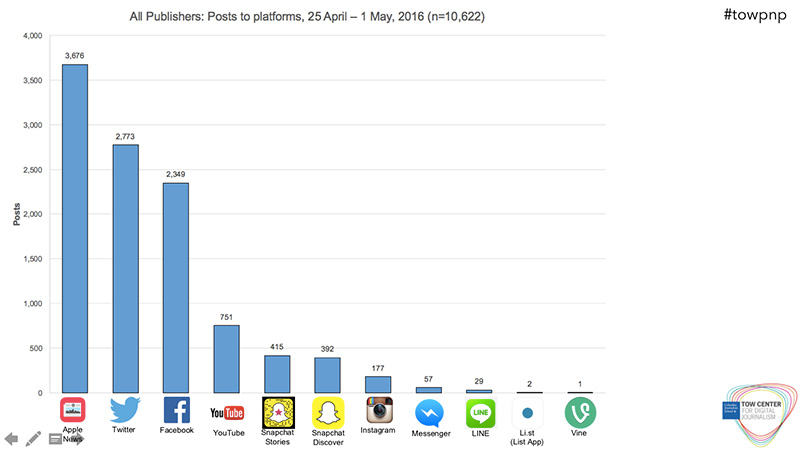

In our quantitative analysis, we looked at nine publishers, chosen for their diversity, across 12 different platforms. While it is clear that most publishers feel the need to be on most platforms, this is not at all reflected in the patterns of posting.

Although publishers are experimenting with new platforms and even messaging apps such as Line and WhatsApp, these still comprise a small minority of posts. Apple News was by far the most posted-to service in our sample, which is partly attributable to the very high volume of stories posted by CNN and The Washington Post and the automated nature of the feed into Apple News.

A closer look at publisher-by-publisher figures for each platform shows the nuances in how different publishers are utilising different outlets. News organizations consistently post a high number of links on Twitter, despite the fact that nearly all publishers we spoke to saw lower referrals back to their own sites from Twitter when compared to Facebook or Google. Another interesting finding is the surge in individual ‘snap stories’ posted on Snapchat by newsrooms that are not present on the Discover channel. Publishers that did not manage to gain a coveted slot on the Discover news page are nevertheless producing ephemeral stories for Snapchat’s avid audience of mostly under-25-year-olds. The New York Times was the only publisher in our week-long analysis that did not produce anything for Snapchat; all eight other outlets published content via Snapchat Discover or Stories.

The most pressing strategic question in newsrooms is how to allocate resources between building a destination and creating journalism that is distributed. Business models dictate how organizations approach the dilemma. Publishers with an advertising-based model view social platforms as perhaps the only way to become sustainable. This “Hail Mary” strategy of publishing as much as possible onto third party platforms reflects the difficult state of the mobile advertising market for most publishers. Those with subscription strategies are very different. They see social platforms as a way to recruit new readers and turn them into paying subscribers, and are therefore more strategic in their posting patterns.

“One of the biggest challenges was really figuring out how this fits in for [us] as a subscription business,” one newspaper social media manager told us. “A lot of platforms just don’t support subscription models.” In our conversations with platform representatives, we heard either anecdotally or directly that most of the major platforms were considering adding features that will drive readers toward subscribing to news organizations.

As one product developer from a technology company put it: “We do see that the ad market is not that great right now for publishers, so subscription might be something we have to look at.”

“We have accepted that everything will be distributed on platforms, and that our control over that is gone,” said an executive in charge of innovation at a large metro news organization. “And what we are left with is thinking how we [can] monetize that relationship with our readers elsewhere.”

This approach contrasts markedly with that of New York Times President and Chief Executive Officer Mark Thompson. Speaking at the Tow Center’s Journalism and Silicon Valley conference in November, Thompson said: “We have to do both [destination and distribution],” adding: “I think we’re moving back to a world of destinations. Facebook wants to be a destination. The issue, and it’s a very interesting point for journalism, is whether you’ve got the guts and the confidence to say we’re going to be a destination ourselves.”

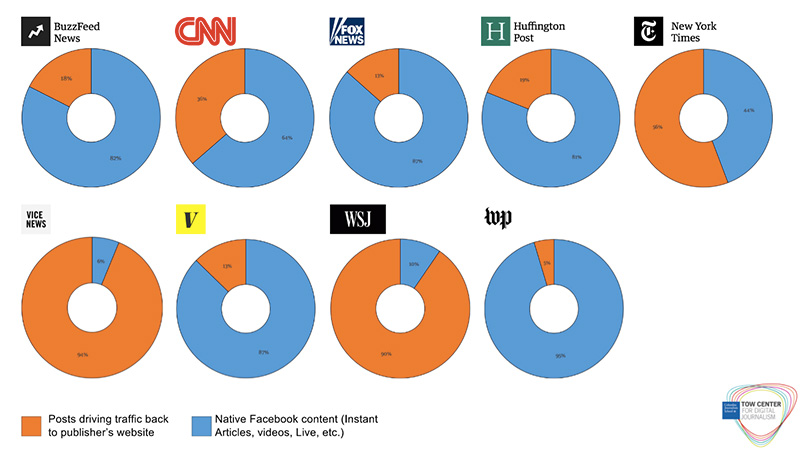

Our data on Facebook Instant Articles, which opened up to all publishers last April, offer a fascinating insight into how publishers think about evaluating the balance between destination and distribution. The Jeff Bezos-owned Washington Post, with its digital advertising model, went “all in” on Instant Articles, a completely different approach from that of the subscription-based Wall Street Journal. The New York Times, as Thompson promised, is perched on the cyber fence, posting almost equal numbers of links back to its own site and Instant Articles, with links back to the Times’ own properties slightly ahead.

Technology companies are in fierce competition with each other, and the publishers that provide material for them are either, as the local news manager quoted earlier put it, “collateral damage,” or beneficiaries of this competition. The clash between Google, Facebook, and Apple, for instance, centers on control of mobile advertising and commerce. Both Apple and Facebook created news products to encourage journalism posted natively to their platforms, while Google has championed the idea of open links and searchable content.

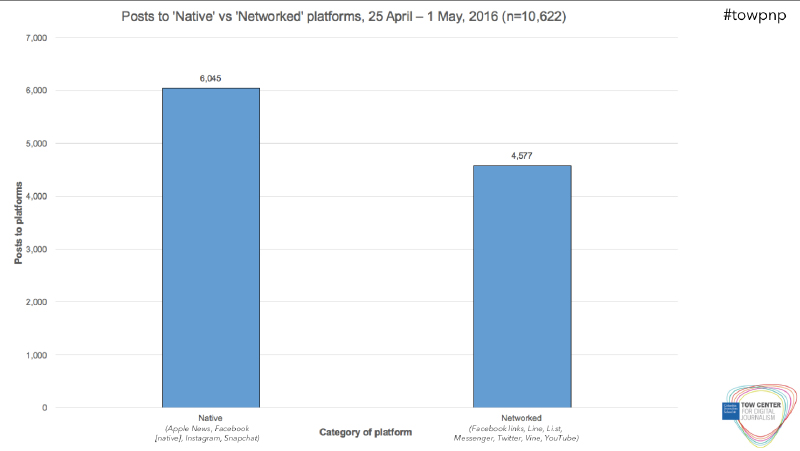

This graph shows articles posted “natively” to platforms where you have to be logged in to the platform to view content, versus links to articles that can be viewed on any site (what we call a “networked destination”).

Of the total number of articles we tracked over the course of a week, most were posted natively to platforms such as Apple News, Facebook Instant Articles, Instagram, or Snapchat. Given that at the beginning of 2015, Instant Articles, Apple News, and Snapchat Discover did not exist, this gives an indication of how rapid adoption has been.

The bad news is that so far there are no clear returns in terms of increased advertising revenue as a result of placing more articles on social platforms. Some publishers reported small increases, while others saw no change at all; we will have to wait for more data before a clearer picture emerges.

Whatever the underlying business models, our interviewees expressed almost universal concern in two areas: data and brand. Despite efforts by platforms to return more data to publishers, there is still a great deal of frustration that the platforms cannot give publishers enough insight into how their journalism is being read.

“The real problem that we have [with readers and viewers on social platforms] is that we just cannot extract enough information about user behavior at every point to make good interventions and ultimately build better news products,” a data scientist at an international news organization told us while discussing distributed articles.

Owning the relationship with the reader or viewer is another way of thinking about “distribution versus destination.” Google’s Accelerated Mobile Pages, for instance, was created expressly with the intention of giving publishers faster loading pages and allowing them to retain data and traffic from user visits. However, when AMPs are viewed as part of the “carousel” of search results, Google has greater control over the overall user experience, with an algorithm deciding which pages appear next to each other.

The question of whether a consumer of journalism “belongs” to the platform that hosts content or to the organization that produces it goes to the very heart of how platforms are becoming more than neutral vectors for links and traffic. If, for instance, Facebook is deciding via its newsfeed algorithm that a reader will see more video through her newsfeed and, also via algorithm, which stories or videos to recommend next, this is an active relationship with the user’s habits and behavior. Facebook and Snapchat both create a publishing environment for display advertising and are directly involved with ad transactions.

At the Journalism and Silicon Valley Tow Center conference, we asked Facebook Product Manager for Instant Articles Michael Reckhow about his perspective on the dynamics of this relationship. “We think of our readers as the customers that we want to serve with great news, great experience,” he said. “And then with publishers, we also treat them as customers, and that’s…the language that we use because I think that explains the role that we play.”

Mark Zuckerberg is adamant that Facebook is just a technology company and not a publisher, yet this is at odds with the idea that the company seeks to attract, retain and own a readership. It was also recently disclosed that a number of publishers were paid to produce more live video specifically to promote Facebook Live.

This deal led to the famous exploding watermelon on BuzzFeed, which was watched by 800,000 people one rather slow Friday afternoon, and even to The New York Times putting an editorial meeting on Facebook Live.

We came across other examples of incentivized partnerships. Some were transparent in nature, such as Google’s partnership with the Times to distribute a million Google Cardboard 3D viewers as part of a Virtual Reality experiment. Others were less significant, such as 360-degree cameras handed to publishers to help them test Facebook’s new panoramic video offering.

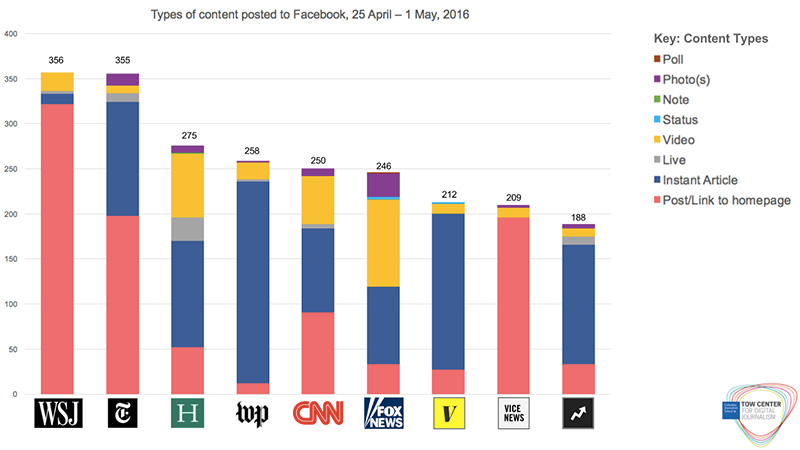

Publishers do not always disclose that Facebook Live broadcasts, for instance, are being paid for in part by Facebook, which raises interesting ethical issues about transparency and more broadly about whether our news ecosystem is being shaped by more than user behaviour. It is clear from looking at what types of material news organizations create on Facebook that not all news outlets are as varied–or as incentivized–as others.

This graph shows the types of content published by news organizations on Facebook

Some interviewees from news organizations were skeptical that social media platforms are “just technology companies.”

“They are publishers, they control the audience in many ways. They’re the gateway to the audience and they determine what they will allow and what they won’t,” one senior executive at a successful publisher told us. “It’s their world. I see them as a partner. We call them a frenemy, and I don’t even know if that’s totally accurate.”

In the past year, we have seen platforms move beyond hosting material into shaping more aspects of news production and distribution. This includes some functions such as format choice, design parameters, ad sales, and audience data collection which were once at the center of a publisher’s business model.

In the new closeness between news organizations and technology companies, the questions who is the publisher? and who owns the audience? are central. At the moment, this debate is viewed mostly in terms of how it affects business models and financial outcomes for commercial news organizations. However, there is a set of concerns and questions relating to the broader public sphere that have gained little visibility and had few resources directed to them by either news organizations or technology and platform companies.

Platforms now must consider significant issues ranging from broad questions of free speech to how to preserve and maintain the integrity of archived material. We have heard growing concern over the opacity of algorithmic and editorial systems that distribute a much more personalized version of news and information, but we do not yet have the right framework to regulate such systems.

The rights of users and citizens who post news material themselves and the ethical use of new tools that expose the public to potential risk, such as live video streams, are still to be worked out. Ultimately, even providing a clear view of the relationship between platform companies and publishers is a matter of public interest.

The relationships between platforms and publishers are complex, fast-changing, and vital to the future of journalism. Our research so far has mapped the territory of this emerging field. Next, we plan to dig deeper to explore the implications for democracy and the public sphere.

The Tow Center research team was lead by research director Claire Wardle, and research was conducted by Tow Fellows Pete Brown, Nushin Rashidian, Priyanjana Bengani, and Alex Goncalves. The Platforms and Publishers project at the Tow Center for Digital Journalism is supported by the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation; John S. and James L. Knight Foundation; The Foundation to Promote Open Society; The Abrams Foundation, Inc.

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.