WHILE PUBLIC RADIO STATIONS across the country fret over the threat of federal-level funding cuts, West Virginia Public Broadcasting has its mind on other matters. A state-level proposal to zero out half of its $10 million budget had the network on the defensive this month. In West Virginia, which national media often portray as Trump Country Ground Zero due to its high proportion of Trump voters, you might expect that the rift is ideological. But the $4.6 million cut was proposed by Democratic governor Jim Justice—a billionaire coal operator who coincidentally owes $4.4 million in back taxes to the state—and some Republicans in the legislature have been quick to come to the network’s defense.

Instead of partisan rancor, the debate over public broadcasting here comes back to the state’s underlying financial crisis. West Virginia has seen its coal tax revenues plummet in recent years, the result of a perfect storm of factors that includes cheap natural gas and competition from western coal reserves. And in a place where it was once taboo for politicians to discuss economic diversification for fear of alienating the coal vote, the legislature has been caught unprepared to fill its yearly $500 million budget hole. West Virginia is not a unique case; other cash-strapped, low-density rural places like Mississippi and Alaska have seen recent proposals for state-level cuts to public broadcasting too.

Since 90 percent of its state funds are used for staffing, WVPB was ready to make 15 layoffs as of March 17. Then, just hours before the dismissals were to occur, Justice reinstated funding in full, with a caveat that WVPB take a year to transition into a “fully integrated part of” West Virginia University, the state’s largest land-grant institution. Currently, WVPB is an autonomous agency of state government. But with the WVU deal still under negotiation, and with the legislature still far from coming to terms with the governor on a budget, the future of the organization remains uncertain. Most of those people consulted for this story agree that cuts and layoffs are still likely.

“Everybody in that chamber realizes that those cameras on us are there because of public broadcasting,” says Sen. Robert Beach

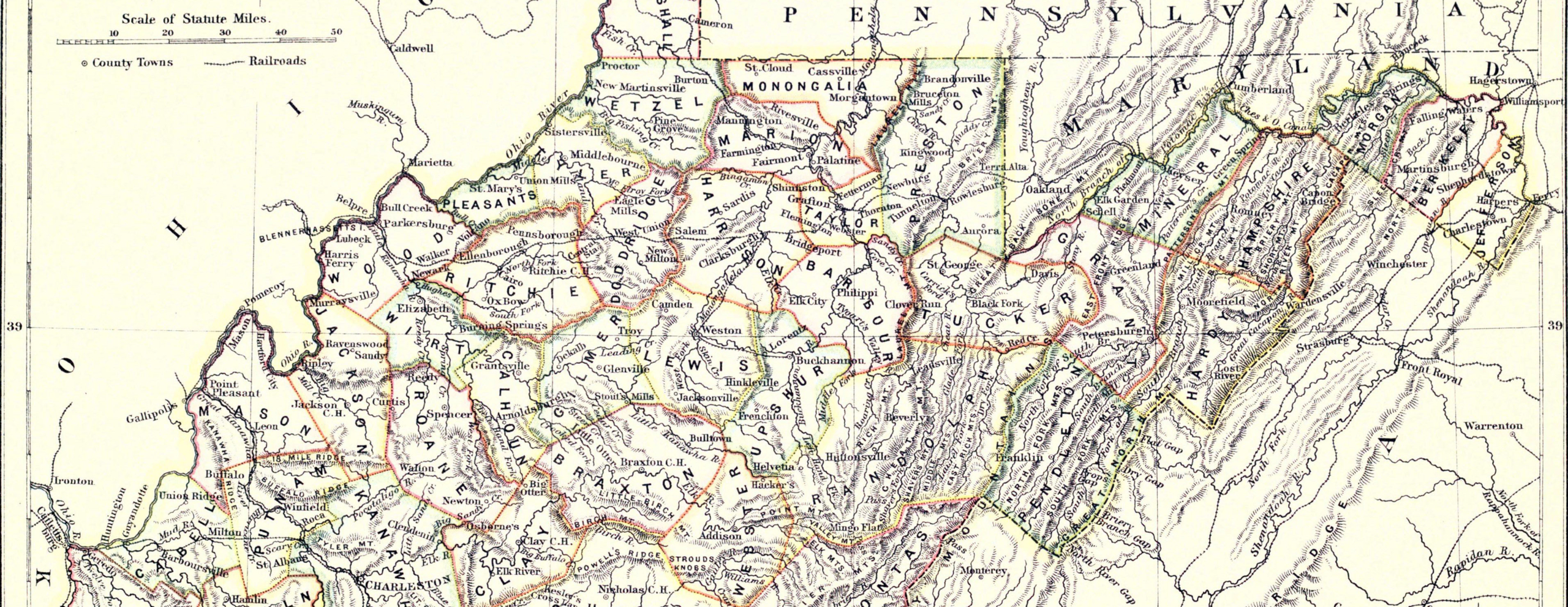

WITH SIX NEWS BUREAUS, WVPB is the only television and radio network devoted to in-depth coverage that reaches all 55 counties of this geographically and culturally diverse state. Some remote areas have no local news coverage to speak of. When disasters strike, like the floods that ravaged some parts of West Virginia last June, WVPB is the only communications network in a position to coordinate statewide relief efforts in real time and devote resources to long-term coverage of the aftermath.

“If WVPB were to go away, I’m not sure who or what would fill the vacuum,” says Maryanne Reed, Dean of the Reed College of Media at West Virginia University. Reed also serves on the board of the Educational Broadcasting Authority of West Virginia, which governs the institution.

WVPB also offers a live feed of the state legislature’s floor discussion, a service that rural people rely on to keep tabs on what’s going on at the statehouse. Lawmakers depend on it too. “Everybody in that chamber realizes that those cameras on us are there because of public broadcasting,” says Sen. Robert Beach, a Democrat. “I’ll get text messages and comments from my constituents about something that happened on the floor, people offering their two cents. It’s important to us that […] people can participate in the process.”

Providing quality educational content to children in low-income households is one of the driving forces behind public broadcasting, and it strives to fulfill that mission here in West Virginia, where a quarter of all children live in poverty. WVPB runs a new 24-hour kid’s channel and serves six thousand educators and homeschool teachers who use the network’s education website.

Some even see it as a public relations device for a place that is trying to retool itself as a tourist destination to balance the loss of revenue from coal. Residents here are often highly sensitive to negative perceptions of outsiders, and Friends of WVPB Chair Susan Hogan calls the West Virginia-based NPR show Mountain Stage the state’s “calling card to the world.” A recent study found that the show, which receives $300,000 in state funding, creates a $1 million economic impact.

Serving an average of 38.5 people per square kilometer means that WVPB is technically defined as a Rural Audience Service Station, which doesn’t make it cheap to run. And while flatter places may get away with one or two transmitters, West Virginia maintains 27 in order to reach every wrinkle between its hills, which residents call “hollers.” If the towers were to go dark, the state would accrue steep fines from the Federal Communications Commission, which penalizes any unused broadcast licenses.

More than one staff member who spoke off the record reports that they are searching for another job, or are concerned that the stress of job insecurity is taking a toll on their health

THE PROPOSED BUDGET CUT CAME as a complete surprise to leaders at WVPB, who hadn’t been consulted by the governor’s office prior to its release. The Friends of WVPB jumped into high gear by hiring a lobbyist and marketer, who launched a #BackInTheBudget campaign to rally support. The network’s development staff, which is prohibited from advocating, created a “value campaign” that now airs a steady stream of promos touting its benefits.

Meanwhile, upper-level management began hosting all-staff meetings about the crisis for an hour or more per week. More than one staff member who spoke off the record reports that they are searching for another job, or are concerned that the stress of job insecurity is taking a toll on their health. Since WVPB is the only public media game in the state, their only option to remain in the sector would be to leave.

Throughout it all, the news department was given the delicate task of covering the state’s budget crisis while also worrying about their own employment. “This has been a big test of how you become a reporter who isn’t entering into the conversation with personal bias,” says Hogan.

WVPB can remain a state agency, with clear visibility and a certain degree of vulnerability to the whims of politicians. Or they can fully claim their independence by becoming a freestanding organization. The third choice is to partner with a university, which comes with its own pros and cons.

SO FAR, NO ONE HAS LAID OUT A PLAN for how a merger with WVU might work. States like Wyoming and Wisconsin provide models, but a spokesperson for the Corporation for Public Broadcasting says statewide networks are typically state licensees rather than university-based.

Further, such a move would be working against the national trend, says Tom Thomas of the public media consulting firm Station Resource Group. More often than not these days, Thomas sees universities spinning off their radio stations into independent entities. However, he says partnerships like this work best with land-grant institutions that have an extension mission, like West Virginia University. And a university may provide a more comfortable place to weather out a financial storm than hanging out in the wind as a standalone entity.

There are basically three choices, Thomas says, and none of them are a slam dunk. WVPB can remain a state agency, with clear visibility and a certain degree of vulnerability to the whims of politicians. Or they can fully claim their independence by becoming a freestanding organization, relying on their own fundraising acumen to stay afloat. The challenge there comes back to West Virginia’s economy more broadly, and whether its citizens have the capacity to support a large nonprofit through gifts and sponsorships.

The third choice is to partner with a university, which comes with its own pros and cons. There’s the obvious economies-of-scale argument: the network could save by sharing the university’s administrative personnel or vehicles. But the university would assume duties it’s never had before, like maintaining transmitters in every corner of the state. “I would personally not like WVU to be going around changing light bulbs on towers,” says Beach. “I think that’s crazy.” He also questions whether potential revenue gains from selling off state-owned assets would truly help balance the budget, calling it “chump change” when viewed alongside the half-billion-dollar budget hole.

Certainly students and journalism departments stand to benefit. The network currently maintains an existing partnership with the Reed College of Media. “We would welcome them with open arms,” says Reed, “but really the question is, ‘Will that result in the kind of coverage the state needs?’ And that I don’t know.”

Thomas says that one of the main challenges of university-based stations is how to raise appropriate questions about costs and accountability within their parent institution. Formulating clear ground rules and appropriate firewalls between news departments and university public affairs departments is critical.

The number one potential pitfall in such scenarios comes back to competing agendas. “The position of public broadcasting stations owned and operated by universities often comes down to ‘How much for us’ versus ‘How much for the new arena for the football team,’” says Thomas. Instead of the whims of a governor, such stations can become subject to those of changing college administrations.

Catherine V. Moore is a writer and radio producer based in West Virginia whose work on Appalachia has appeared in The Oxford American, VICE.com, Yes!, Virginia Quarterly Review, and others. More info on her work at beautymountainstudio.com.