Sign up for the daily CJR newsletter.

One morning in December of 2021, Argie Tidmore, the owner of two radio stations, WPPA and WAVT, in Pottsville, Pennsylvania, woke up to alarms on his phone warning that something was wrong with the stations’ transmission. Tidmore raced to check on the towers, which sit atop a hill in an eight-acre clearing surrounded by woods. There, he immediately saw the damage.

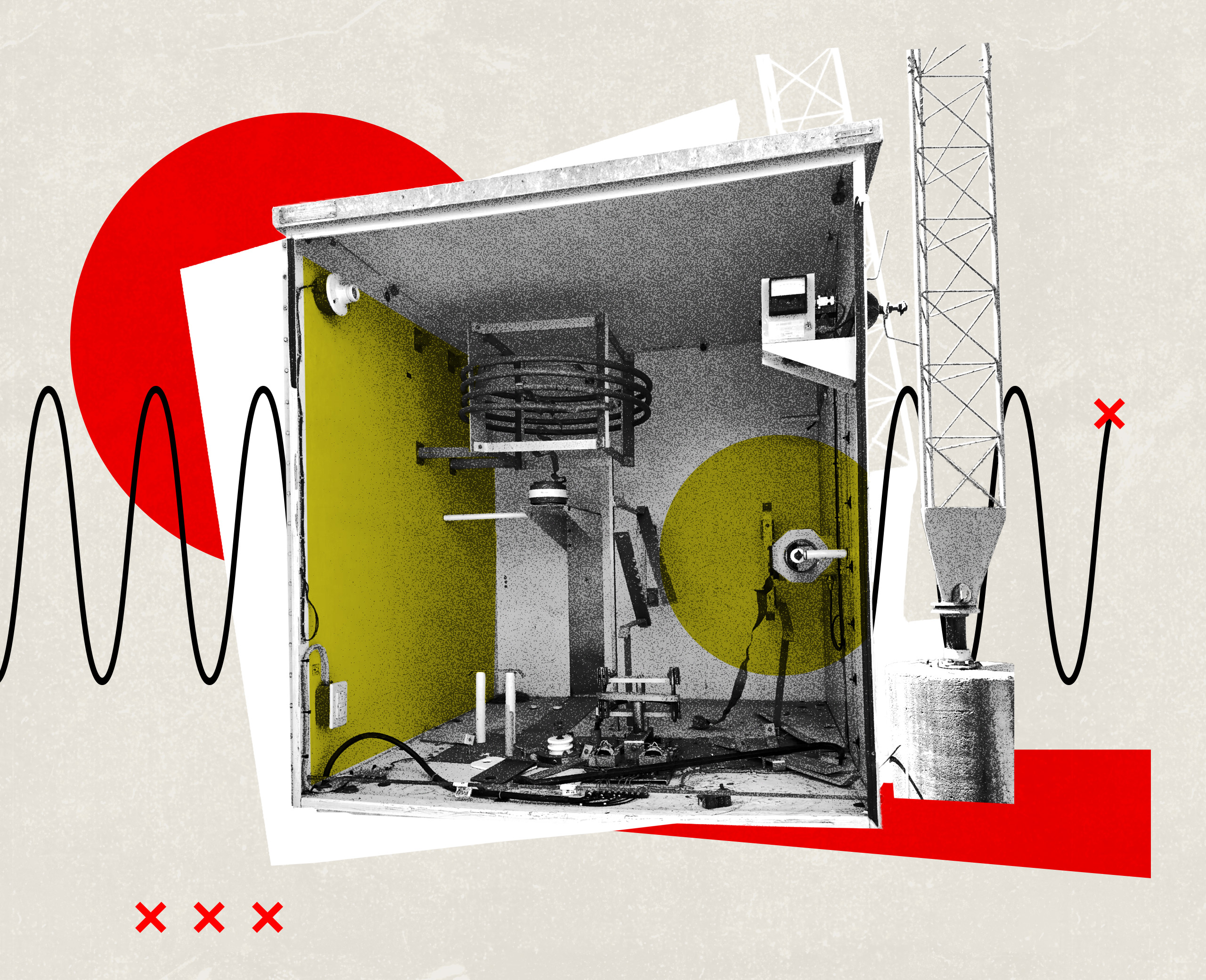

Thieves had yanked radio equipment out of the ground around the towers, bashed doors open, and destroyed the guts of the system. Their target: the three hundred and fifty square feet of copper wire that spiderwebs throughout the towers and into the earth. Tidmore said that even the massive cables buried deep in the ground were stolen. “They must have had to hook it to the bumper of their car or their truck,” Tidmore said.

Tidmore’s stations are small, and they were already under strain from the difficulties that affect radio stations in many small American towns: the challenges of hiring new talent, and competition from platforms such as Spotify. Besides, this was the third time this had happened to him in a five-year period. Though Tidmore’s insurance covered repairs, the theft of the copper wiring was yet another setback.

Copper wire robbery is a concern that’s on the rise for small stations like Tidmore’s, given the high price of copper—currently about six dollars per pound. More than fifty-seven hundred similar incidents of copper theft affected communications infrastructure, including radio stations, between June and December of 2024, according to a report by USTelecom, an organization that represents telecommunications-related businesses in the US. In the following six-month period, according to the same report, that figure nearly doubled.

“The value of copper has gone up dramatically,” said Ben Stickle, a professor of criminal justice administration at Middle Tennessee State University and the author of Metal Scrappers and Thieves: Scavenging for Survival and Profit. “Because it is so much more valuable, thieves took notice and started stealing it to recycle it and get cash.”

Ivette Butron Ramos, the owner of Butron Media, is still recovering from the shock and expense of a copper robbery last June. Her station’s insurance did not cover the total repair, which cost tens of thousands of dollars. She believes the thieves likely only got a few hundred dollars for the metal. “I always say it would have been better if they had come to my office and asked for the money instead,” Butron Ramos said.

Her station, 1030 WGSF-AM, the longest-running Spanish-language station in Memphis, wasn’t able to broadcast for six months after the theft occurred. “They destroyed a whole outlet for a few hundred dollars,” Butron Ramos said. By December of 2024, the station had only resumed broadcasting during daytime hours.

AM stations like Butron Media’s can be especially vulnerable to thefts of their copper wiring. Stations on the AM band have a cluster of 120 wires buried in the ground in a star-shape pattern inside, beneath, and around their towers. The wires can be a few yards or several hundred feet long, depending on the station’s frequency. “Folks have realized that for every one of these towers, there’s 180 pieces of copper,” Rob Bertrand, the CEO of Inrush Broadcast Services, an engineering firm that regularly fixes damage caused by copper wire theft, said.

The Federal Communications Commission has acknowledged the problem: “It is a core mission of the FCC to expand communication services to all Americans, and one of the things that’s undermining our ability to do this is copper theft or infrastructure vandalism,” Olivia Trusty, an FCC commissioner, said. She noted that such theft can affect such services as the 911 system and the energy grid. Trusty has addressed the concern publicly on multiple occasions. Asked where this problem ranks in her list of concerns, she said, “At the top of the list.”

She also said that, practically speaking, there isn’t much the FCC can do to combat the problem beyond raising awareness. The FCC, for its part, does not have jurisdiction over criminal law when it comes to copper theft, so there are no plans to devote funds to the concern.

Tidmore said that it’s unlikely the situation will change, as even preventive measures don’t work. Towers are often in secluded areas where it is too dark for cameras to catch criminal activity. He’s considering supergluing an AirTag onto one of the larger copper straps used to ground the tower. “So if they did take it, you could kind of see where they went,” he said.

For Tidmore, dealing with copper theft is a bit like having car trouble. People don’t often think anything is going to go wrong. “Every day a car works,” he said, “but when there’s a problem, that becomes top of the list.”

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.