DETROIT, Michigan — On a chilly October morning inside a WeWork building in downtown Detroit, the team of the Gander newsroom congregated for the first time in months. The small group of local Michiganders, two reporters and two editors, sat down inside a slightly overheated office room with polka dotted wallpaper. The team was gathered to strategize about their coverage of one of the fiercest battles in their state: the fight for reproductive rights.

Scattered across the table were loose meeting notes, neon-colored sharpies, and black WeWork coffee mugs. Since the Gander doesn’t have a physical newsroom, booking a WeWork office space is usually the most convenient option. Lisa Hayes, the managing editor, sat at the end of the table wearing darkly framed glasses and an all-black outfit. She walked over to a nearby whiteboard to draw a calendar. The meeting was at a crucial time with less than two weeks until the midterm election.

“This is just to keep in mind what we have time for,” Hayes said, nodding towards the board.

After the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision in June to overturn Roe v. Wade, Michigan became the epicenter in the battle of whether to re-criminalize abortion. Michigan was one of five states that had reproductive rights on the ballot, leaving it to voters to decide whether the state’s 1931 abortion ban should be enforced once again (on November 8th, Michiganders voted against it). In the lead up to the midterm election, reproductive rights became a central topic to the Gander’s reporting with stories praising Democratic candidates’ actions to protect abortion and highlighting Republicans’ attempts to reinforce the ban.

Local reporters at the Gander Newsroom meet in-person to discuss their coverage of reproductive rights.

The Gander is part of the Courier Network, a company which supports liberal politics run by Tara McGowan. McGowan launched the network of eight news outlets as part of ACRONYM — a 501(c)(4) non-profit organization she started. She also launched the super PAC, PACRONYM, which received support from Democratic donors such as Steven Spielberg, J.J. Abrams, and LinkedIn co-founder Reid Hoffman. In an internal memo, ACRONYM announced that they planned to raise $75 million to impact the 2020 election cycle. In 2021, Vox reported that McGowan was launching Project for Good Information with the intention of raising $65 million to push progressive local news around the US. While previously owned by ACRONYM, Courier is today owned by Good Information Inc.

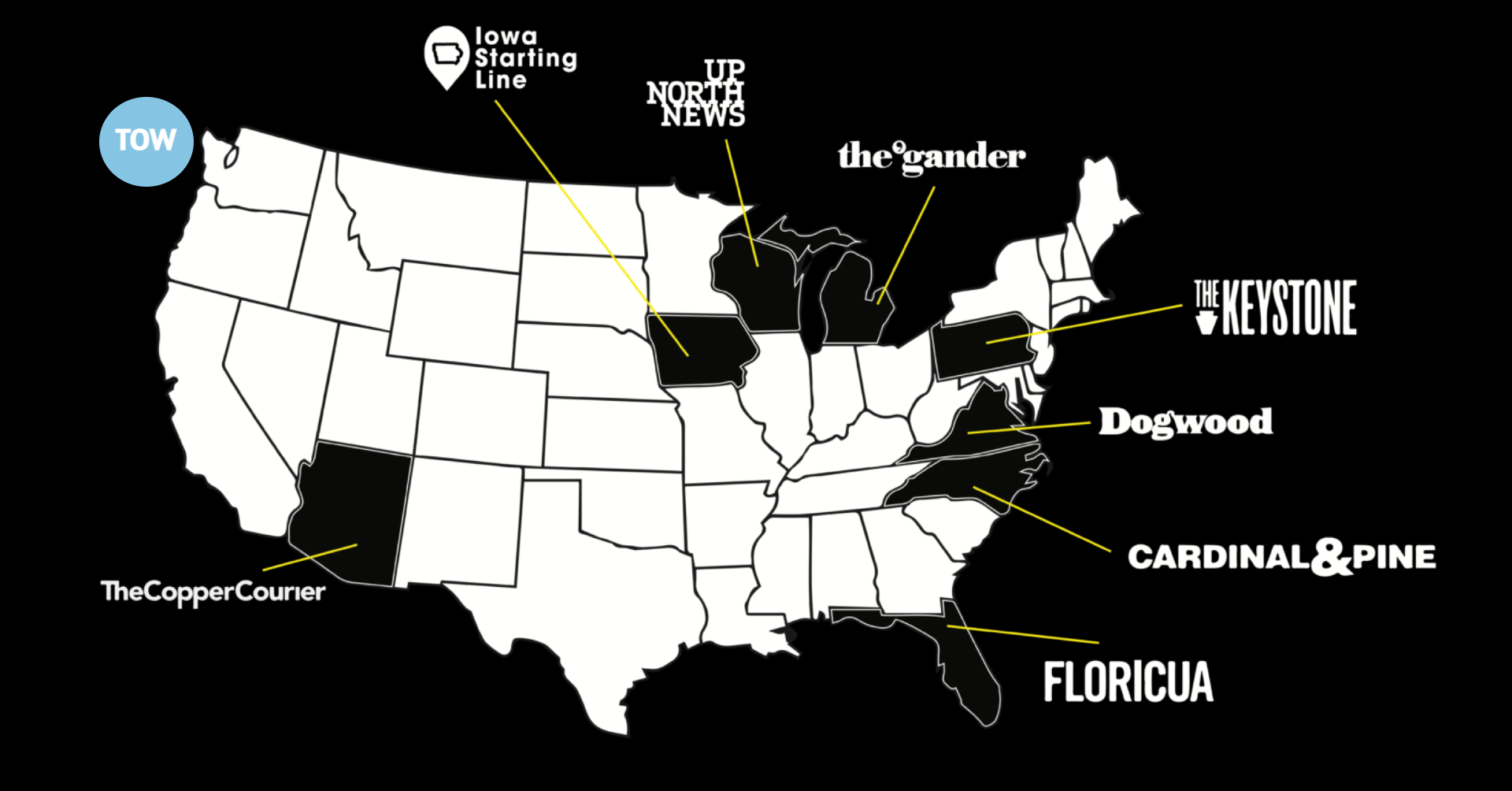

Courier has seven other newsrooms in competitive swing states across the county: Arizona, Florida, Iowa, North Carolina, Pennsylvania, Virginia, and Wisconsin. As recently reported by Wired, McGowan created the newsrooms with the intention of neutralizing false or “bad information” by conservative media. The goal of Courier is to flood the information ecosystem with progressive news, or what McGowan calls “good information.” It is a strategy some critics depict as fighting fire with fire.

While some outside journalists are highly skeptical about Courier Newsroom and its leadership, the reporters gathered at the Gander’s WeWork table that morning all seemed dedicated to its mission. The youngest reporter, Hope O’Dell, 23, who graduated from Michigan State University in May, said that they appreciate being able to cover topics that align with their journalistic ethics. “I am for progressive journalism in the way that I don’t want to amplify misinformation or hate or draw false equivalency between two opinions when one is clearly false or just not true,” they told me.

Some reporters credit the newsroom’s unique approach with restoring their dented faith in journalism entirely. Hayes, the managing editor and also a Michigan State Alumni, worked as a reporter and magazine writer earlier in her career for outlets such as Traverse Magazine, before switching careers to teaching at a local college.

“I thought that journalism was no longer an option for me,” she said. “I had been frustrated by the changes of the world with clickbait and how to be a productive part of journalism.” But when a friend mentioned that Courier, an impact first organization, was looking for a managing editor for its Michigan Newsroom, she decided to apply. “It sounded like a really good opportunity to get back into the field.”

The team at the Gander say their aim is to provide factual news about reproductive rights to “passive” news consumers, which include voters who don’t pay for news or who get most of their information from skimming headlines on social media. To get the attention of this audience, the Gander reporters mostly publish short videos, graphics and skimmable newsletters on its social media channels. Articles range from stories on local faith leader’s pro-abortion stand to fact-checking what Republican candidate Governor Tudor Dixon says in debates. O’Dell has been especially active on their TikTok page, with posts coming out by the hour.

“Every week I do a set of infographic cards,” O’Dell said. “There’s one with a statistic like polling data about what Michiganders believe about abortion or the proposal regarding reproductive freedom. I do one debunking misinformation about abortion, usually like the medical procedure.”

@gandernewsroom In the second and final governor’s debate between Democratic Gov. Gretchen Whitmer and Republican candidate Tudor Dixon, Dixon claimed that Gov. Whitmer voted against banning “partial-birth abortions.” This is false, because that procedure has been federally banned since 2003 – and they’re not even real. #michigan #roevwade #midterms2022 #michigangovernorrace #michiganpolitics #michiganelection #tudordixon #gretchenwhitmer ♬ original sound – The Gander

While the Gander works like a seemingly normal newsroom, the process going on behind the scenes at Courier’s headquarter team has led critics to compare it to political campaigning. The newsroom has borrowed the political tactics of ‘microtargeting,’ whereby particular messages are tailored to unique slices of the population in a bid to boost turnout at voting booths. Employees at Courier’s headquarters are responsible for testing whether content produced by its local newsrooms is successful in moving voters in a desired progressive direction. For instance, in the lead up to the midterm elections, Courier tested whether exposing people to content produced by the Gander could influence voters’ view on re-criminalizing abortion. In a study, they exposed 5,200 voters to a Facebook ad that linked to an article entitled “Six in 10 Michiganders Oppose Re-Criminalizing Abortion. Here’s What One of Them Has to Say.”

The results showed participants were four points more opposed to re-criminalizing abortion, and that they increased their support for Governor Whitmer’s lawsuit to prevent an abortion ban. According to Courier’s data advisor, Pete Backof, this is an enormous shift. “The most successful television ads that people test right now come in at 1.2 – 1.5 percentage point shifts. So to be able to show a four-point effect is really big,” Backof said, who prior to Courier worked on the analytic team for the 2012 Obama campaign. The ads were likely so successful, he theorized, because the target audience typically aren’t exposed to a lot of news sources which makes them more sensitive to politically charged information.

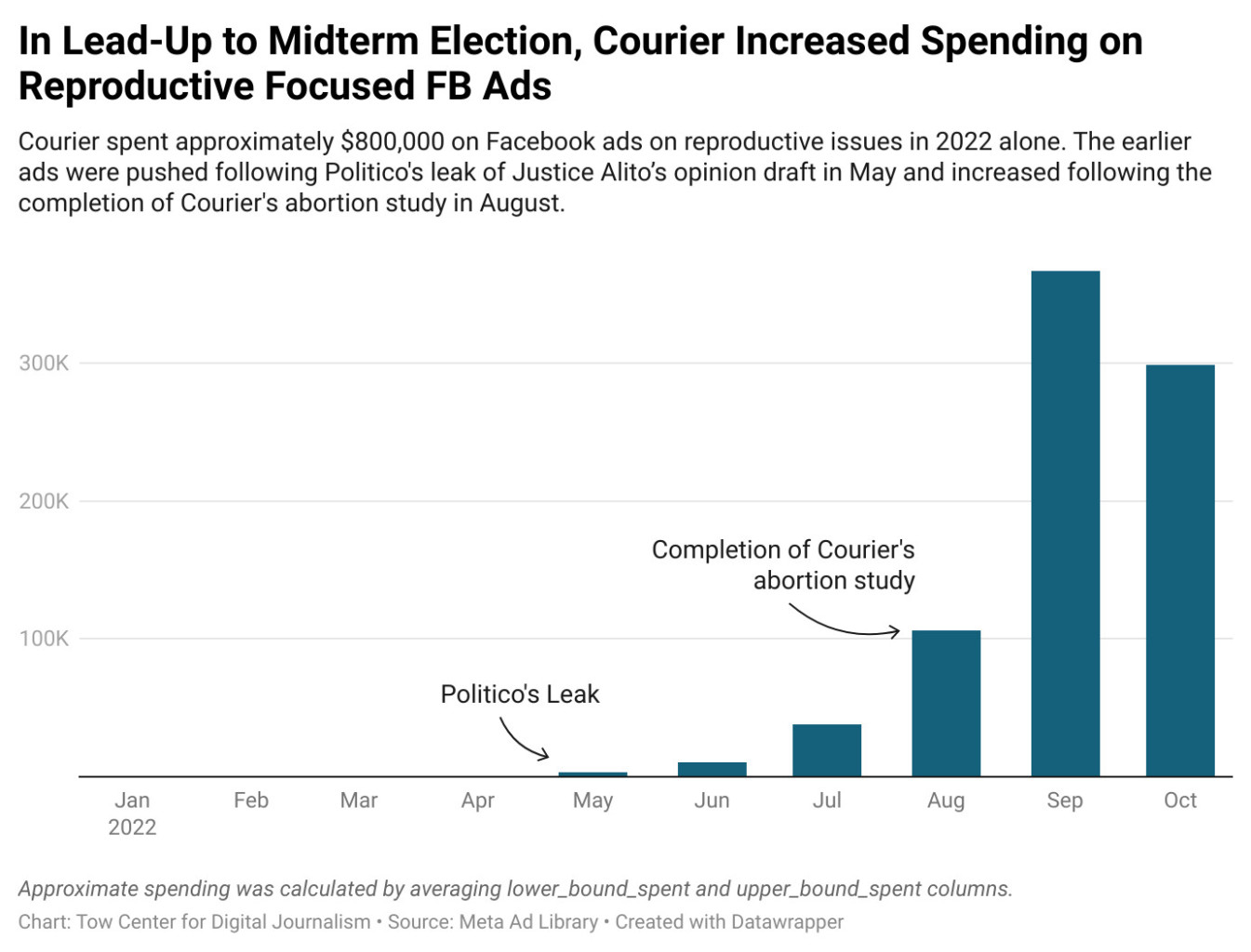

The testing helped steer Courier’s coverage on abortion, ultimately confirming that reproductive content was effective in influencing voter’s opinion. In 2022, Courier has spent approximately $800,000 as of mid-November on showing abortion-related FB ads to target voters, according to data from Meta’s ad library. The earlier ads were pushed following Politico’s leak of Justice Alito’s opinion draft in May and increased following the completion of the abortion study in August. These ads were viewed more by women between the ages of 25 and 34 than any other demographic. Courier uses Facebook ads to micro-target infrequent voters in swing states who would likely vote for the Democratic party. As reported by Bloomberg, these Facebook ads feature politically salient topics from bashing Donald Trump’s response during the pandemic to highlighting a Democratic candidate’s bill to end child care deserts.

See here for data analysis.

Courier’s communications director RC Di Mezzo, a 26-year-old wearing a green New York Parks cap, flew in from upstate New York to oversee my meeting with the Gander. The main purpose behind the testing, Mezzo said, is to validate Courier’s model and mission to external partners.

“It helps build goodwill and credibility with folks in different media circles — our testing lets folks know that we’re not just spinning our wheels here, but that our model and mission are objectively effective,” he told me from a Detroit sports bar.

There isn’t anything unusual or radical about news organizations having an ideological perspective, according to Matthew Pressman, an associate Professor of Journalism at Seton Hall University. Many other news organizations have done that in the past, and as long as they are transparent, it doesn’t necessarily have to be a problem. The United States, he said, is actually more of an outlier in its professed devotion to objectivity compared to Europe and other parts of the globe. However, Courier’s dedicated goal of swaying voters in a particular political direction through methodological testing and Facebook ads is where “things become dicey,” and the line between journalism and political campaigning blurry.

“There’s advocacy journalism which is one thing, but this is more the kind of thing that you’d expect to see from a political campaign,” Pressman said. “It seems that at a minimum maybe they should spin that off into another organization that more explicitly has it as their mission to change minds and influence voters.”

However, the editors at the Gander see the testing as a positive thing that helps build faith in their work. While the two younger reporters went out for their lunch break, Hayes and the other editor Kyle Kaminski stayed behind at the WeWork office. “It is so rewarding to have something come out that says you’ve reached people, and you are getting people interested in voting,” Hayes said when asked about the testing. She added that she wasn’t informed about the results until after the study had been completed.

Kaminski also jumped in:

“It was the first time that I’ve seen work making a difference rather than just like looking at numbers and which stories got the most clicks today,” he said. “This is showing that not only are people reading it, but it’s making a difference.”

A Lack of Bothsideism

The Gander, like Courier’s other seven newsrooms, avoids what’s called ‘bothsidesism.’ The basic idea being that there’s a tendency in journalism to represent both sides of an argument, which presents things as equal, although they might not be. Courier leans away from that, instead focusing on the argument that aligns with their political values without showing the opposition’s side of view.

In Courier’s early years, before separating from ACRONYM, it was criticized for failing to be transparent about its political intentions. This led the media watchdog NewsGuard, which rates the credibility of newsrooms, to give Courier a red rating. They wrote in their report that: “because CourierNewsroom.com is not upfront about its partisan agenda, yet advances that agenda through its story selection and framing, NewsGuard has determined that the site does not gather and present information responsibly and that it does not responsibly handle the difference between news and opinion.”

Since then, Courier has attempted to become more transparent about its political intentions and, to some degree, its funders. A list of funders who have donated over $25,000 can be obtained upon request, according to Courier’s website.

In 2021, Courier hired NYU journalism professor and media critic Jay Rosen as a consultant to help with what he calls their “transparency problems.” Rosen has previously written about the potential for viewpoint transparency on his blog PressThink. Together, he and CEO McGowan created ‘coming from’ statements on the eight newsroom’s about pages. The statements differ for each newsroom, and are intended to communicate its values and editorial decisions. For instance, the Gander claims to support equal-opportunity education and initiatives to reduce the harmful effects of climate change, while the Pennsylvania newsroom, the Keystone, mentions that they cover restrictions on health care, birth control, and abortion care that has been implemented by Republican-controlled state legislature.

According to Rosen, Democracy would be better off if journalists didn’t adhere to the conventional standards of objectivity. Rather than trying to be impartial, he advocated for journalists and newsrooms to be transparent about their values and editorial decisions. Courier was an excellent opportunity for Rosen to see how such a transparent approach could unfold in real life.

“This is one way that I do my work as a journalism professor,” he said. “I like to test my ideas in real world conditions.”

‘Bothsideism’ remains a heated debate within circles of journalism and media critics. Some say it’s important to inform the public of all viewpoints, whereas others say not all viewpoints are important to amplify, especially if they’re based on misinformation and false statements. For instance, mitigating climate change will be increasingly difficult if journalists give equal space to arguments from climate denialists. But most scenarios are not as black and white, and there are many issues that have valid arguments on both sides. A newsroom that repeats political talking points without any critical engagement whatsoever makes it difficult to assess whether it’s actually performing journalism rather than political campaigning.

According to a study by Pew Research Center, journalists are cut in the middle on whether to represent both sides. About 55 percent of the journalists surveyed say that “every side does not always deserve equal coverage in the news.” The study also found that it’s usually younger journalists from left-leaning publications who say equal coverage is not always merited.

The Rise of Partisan Local News

Partisan local news such as Courier are becoming increasingly common in today’s media landscape on both the left and the right side of the political spectrum. For instance, Axios found a network of at least 51 ostensible local media sites promoting Democrat-aligned news content in battleground states for the midterm election. On the right, the Tow Center found a network of 1,200 sites by Metric Media, which appears as local news while promoting conservative talking points and collects user data. This low-cost automated story generation from newsrooms masquerading as local media outlets is known as ‘pink-slime’ journalism.

However, while Courier do attempt to sway swing state voters in a desired political direction, they differ from media companies like Metric Media and Local Report Inc. in two significant ways: first, they are transparent about their political agenda, and second, most of their content is published by actual local reporters from each newsroom.

The reporters at the Gander all live in Michigan and have covered news for local publications before. For instance O’Dell, unlike the anonymous bylines of Metric Media, has grown up in Michigan and understands its politics and idiosyncrasies. In contrast, over 90 percent of the stories by Metric Media are algorithmically generated and they don’t disclose their political agenda on their about page.

While a majority of their reporting is local to each newsroom, Courier also has editors that publish national coverage across its eight platforms. This can lead to some duplication. For instance, two almost identical articles about Biden’s contribution to the Democratic party were published in Courier’s Virginia and Arizona newsrooms with small adjustments to contextualize it within each state. This kind of national coverage is supposed to keep passive news consumers updated on the very basics of U.S national politics. Reporters at the Gander aren’t supposed to touch such broad coverage and instead stay grounded in their state.

“We want them focused on Michigan,” said Di Mezzo, the communications director. “We want them focused on what [local politicians] Gretchen Whitmer, Dana Nessel, and Joslyn Benson are doing, not everything that flies out of Donald Trump’s mouth or the hot topic on Morning Joe.”

This leaves Courier in a gray area. While the news organization has responded to much of the criticism by media critics and journalists in the past two years, they continue to receive millions of dollars from liberal donors to influence voter turnout through content and Facebook ads which is strengthened through their testing. This makes it hard to place them, but they seem to be sailing in a rocky boat between journalism and political campaigning.

It’s a ship the reporters I met in the Gander‘s WeWork are happy to be sailing in. When reporter Isaac Constans, 26, returned from his lunch break, I asked him about Courier’s values-driven coverage. Far from flinching from the criticisms of Courier’s ‘political’ approach, from industry watchdogs like NewsGuard, he embraced them as reasons to work there. Constans, who was in college during the tumultuous Trump years, recalls being sat in classes hearing about how false balance and bothsidesism were an “existential threat to democracy and the viability of media organizations in the US.”

He was driven by a different approach to reporting, one embodied by Courier. When he discovered this, he said, raising his hands and imitating a bomb exploding above his head, “it was sort of like that emoji” 🤯.

Update: This piece has been amended to clarify the relationship between PACRONYM, Project for Good Information, and Courier Newsroom.