Sign up for the daily CJR newsletter.

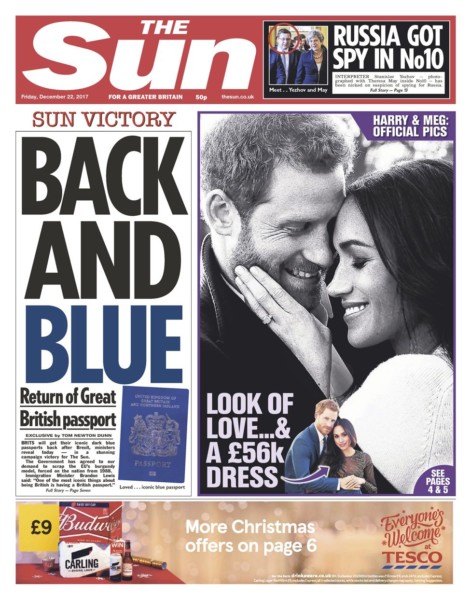

When the British government announced just before Christmas that UK citizens would be issued blue passports after Brexit—replacing the current burgundy model connoting European Union membership—popular right-wing tabloid The Sun credited itself with a “stunning Brexit victory.” The paper had, it said, waged a “determined 17 month campaign” for a reversion to the “iconic” former passport color, which it called a symbol of British identity and national pride.

Papers on the other side of the Brexit debate were less impressed by the blue passport announcement, ridiculing the triumphalism of The Sun and others as irrelevant parochialism. The Guardian (satirically) suggested bringing back other anachronisms like the death penalty, incandescent light bulbs, and “room-temperature free school milk.” A sketch-writer for The Independent called the passport story “a fun festive reminder of the Spirit of Utter Drivel that so needlessly broke a nation,” while the site ran news stories on successive days reminding readers that Britain could have gone back to blue without voting to leave the EU at all.

ICYMI: A viral tweet by a prominent journalist slamming Fox News was completely wrong

Passport-gate is symptomatic of the British media’s widening divide on Brexit: Strongly opinionated voices—both pro- and anti-European—are ascendant, while those closer to the ground are struggling to be heard. The referendum in June 2016 was originally supposed to close a festering wound in British politics, putting the question of Britain’s relationship with Europe to bed once and for all. The surprise result, however, deepened a schism in public opinion. “The written press reflects the divisions in the country,” says talk radio host and commentator Iain Dale. “I think you’ll find, in most of the country, that the shift in public opinion has not been great since the referendum.”

Acrimonious coverage aimed at a divided country should feel increasingly familiar to American readers. Since Donald Trump became president, traditionally straight-laced papers like The New York Times and The Wall Street Journal have cut their coverage with pointed takes, while outlets that have long taken sides, like MSNBC and Fox, have doubled down on one-sided advocacy—feeding consumers hungry for news that chimes with their preconceived worldview. In the UK, this type of partisanship is a longstanding feature of the national landscape. Print newspapers, in particular, have always dictated the terms of political debate: drawing the battlelines on which politicians duke it out, and taking a “tell, don’t show” approach to endorsements at election time.

Brexit was a Trump moment before Trump —it cleaved the country in two, and remains extraordinarily divisive. As American outlets pivot to partisanship, British papers are doubling down on the model. But there are crucial differences between Brexit and Trump. Trump is an elected politician acting out a time-limited, largely reversible mandate, whereas Brexit means irreversible constitutional reset—a blank slate that puts Britain’s culture, self-image, and future role on the world stage up for grabs. Coverage in Britain should reflect that Brexit is not a closed book, and that all is still to play for.

As Brexit negotiations move forward in 2018, the public needs a clear-headed understanding of what’s at stake. But at the moment, different outlets offer such starkly different views (and, sometimes, facts) on the same developments to the Brexit plan that the average reader is left bewildered. “There isn’t a concept of ‘does the British press fairly present the negotiations?’” says Polly Toynbee, a columnist for The Guardian. “The British press is a campaigning organization.”

Brexit was cast as a case study in newspapers’ outsize influence on public opinion. Right-wing tabloids like The Sun, the Daily Mail, and the Express saw Brexit as the vindication of years of headlines labeling the EU a bloated bureaucratic nightmare, an impediment to Britain’s prosperity, and an open door to immigration. Somewhat less influential, but no less vocal, were broadsheet newspapers that backed the “Remain” campaign. The Guardian, the Independent, and the Financial Times all said a vote to “Leave” would be a catastrophic economic mistake, among broader arguments about identity and continental solidarity. (This reporter worked for the Remain campaign in the run-up to the Brexit vote.)

A year and a half on, Britain’s opinionated press hasn’t really evolved its tone; it rehashes the vote on a near-daily basis. As media commentator Roy Greenslade pointed out in October 2016, Conservative Prime Minister Theresa May’s first big Brexit speech was hailed on the right—The Sun called her “a confident, capable female Prime Minister we can be proud of on the world stage,” as the Mail proclaimed “a huge moment in the nation’s history”—but panned on the left and in the center—the Financial Times declared May’s speech “predictably heavy on patriotic emotion and light on strategy,” and The Times called her message that Brexit would be costless for Britain “false and irresponsible.”

Since then papers on the right have grown increasingly bitter, accusing May of selling out under pressure from EU bureaucrats and pro-Europe politicians in her own party—for example when she agreed Britain would pay a $53 billion “divorce bill” as a precondition for starting trade talks with Europe. In mid-November, meanwhile, the pro-Brexit Telegraph mocked up front-page portraits of 15 Conservative politicians under the screaming headline “The Brexit mutineers.” Their crime? Considering voting against legislation that would enshrine a precise Brexit date into law. (The Guardian reported that the politicians in question received threats after the splash.)

The Daily Telegraph this week described 15 Tory MPs as 'the Brexit Mutineers' #bbcqt pic.twitter.com/ER88WL7dpw

— BBC Question Time (@bbcquestiontime) November 16, 2017

That the Brexit debate frequently descends into angry or symbolic tit-for-tat reflects, at least in part, a long-term deficit in the British media’s understanding of how the EU actually works. Where British politics is theatrically adversarial, Europe is consensual, dry, and arcane. “At one point, The Sun ended up having a [story] about two aides having sex in the toilet or something, because that was pretty much the most access they could get,” says Martin Moore, a media expert at King’s College London. “We’ve had 25 years of not covering policy within the EU, so I think the fact we aren’t getting that much policy discussion now isn’t particularly surprising.”

Some outlets are reliably covering Brexit talks, which are secretive, boring, and technical. Broadsheets like The Times and The Guardian are making a greater effort than their tabloid counterparts—even if their opinion pages sometimes lapse into glib caricature. And digital outlets like Politico and BuzzFeed, which have sprouted prominent UK arms in recent years, often boast fresher, clearer-eyed coverage of big issues than the old guard. BuzzFeed’s Europe editor Alberto Nardelli has a talent for boiling complex policy points down to neat, fun explainers, while Politico’s Brexit coverage has leaned heavily on its well-established team on the ground in Brussels. A recent profile of David Davis—the cabinet minister charged with engineering Britain’s exit from the EU—for example, was a well-rounded portrait of an increasingly divisive figure.

UK broadcasters, too, tend to pride themselves on scrupulous fairness. ITV and Channel 4 have done laudably straight journalism around Brexit. And the BBC, which has long had to balance serious agenda-setting clout with taxpayer-mandated impartiality, has approached the process with similar seriousness. “We do believe that there are verifiable and accepted fact sets out there, and we think the endless relativization of news among certain parts of the audience is not good for a strong national news culture,” says Jamie Angus, deputy director of the BBC World Service Group. “BBC News does not believe it’s OK to endlessly say ‘my fact is worth as much as your fact.’”

ICYMI: Merriam-Webster reveals its word of the year

But in the construction of grand national narratives, detailed factual reporting has always struggled to be heard over shouty old-school print publications. The BBC, for example, has been assailed by partisans (and the newspapers they read) on both sides of the Brexit debate ever since the referendum was called.

During the campaign, many Remainers accused the network of false equivalency—cowed, by its duty to provide balance, into treating pro-Brexit lies as valid claims. They were particularly outraged when a month before the referendum, Conservative politician Penny Mordaunt told the BBC’s Andrew Marr that Britain did not have a veto over Turkey joining the EU; in reality any accession to the bloc must be unanimously approved by member states. Although Marr pushed back the first time she said it, he didn’t definitively overrule her, and subsequent packaging of the interview failed to provide factual context.

During the campaign, pro-Brexit Conservative politician Penny Mordaunt told the BBC’s Andrew Marr that Britain did not have a veto over Turkish membership of the EU—a false claim.

At the same time, many of those on the Brexit side bemoaned what they saw as the BBC’s institutional pro-European bias. Despite BBC efforts to beef up analysis and fact-checking features in response to audience feedback, neither of these narratives has changed much since the vote. In recent months, a handful of pro-Brexit government ministers have even called for the BBC to be more “patriotic” in its reporting.

Cabinet minister Andrea Leadsom, who campaigned prominently for Brexit, tells BBC interviewer Emily Maitlis that broadcasters should be “a bit patriotic” in response to questions about stalled negotiations in June 2017.

Angus says the fact the BBC is taking flak from both sides indicates its even-handedness. But Charlie Beckett, a former senior producer at the broadcaster who now teaches at the London School of Economics, doesn’t think it constitutes a clean bill of health. “This is a more fundamental crisis for them. People are undermining the BBC’s role; they’re saying ‘we don’t trust you, we think you’re proactively biased,’” he says. “They’re managing it quite well, but it’s a very difficult story to report on in a balanced way, because it is so polarized.”

Other sections of the media that should be well-placed to report on the minutiae of Brexit are also being shouted over. Local newspapers, for example, have keen insight into the micro-level consequences Brexit could have for individual towns and cities in the UK—many of which receive significant funding for infrastructure, education, and development direct from Europe, and boast industries heavily affected by European regulations.

Local reporter Patrick Daly reports out of London for three titles in vastly different parts of the country—Hull and Grimsby, which both voted heavily for Brexit, and Bristol, which voted convincingly for Remain. “Nearly all politics needs to have a local prism. The reason why Hull and Grimsby hate the EU is that they are sure that the European Union killed their fishing industry,” he says. “For Bristol one of the big stories I wrote much earlier on in the negotiations was how Bristol Zoo could be affected by the fact freedom of movement also applies to animals.”

But local news in the UK is, if anything, in even more dire financial straits than its US counterpart. Where strong local papers do persist, they rarely have the time or resources to focus on meaty policy questions handed down from the international level. In days past, they may have had their own dedicated Westminster correspondents. Now, they’re lucky if they share one, or employ one part-time. “In the long term, Brexit as a story will be hindered the more we have to chop,” Daly says.

British journalists and media-watchers interviewed for this piece consistently said British papers have been reliant on old partisan arguments around Brexit—those on the left catastrophizing every development, those on the right by turns triumphalist and suspicious that their victory is being secretly undermined by pro-Europe elements. While many observers understand the difficulties of reporting on uncertain and opaque negotiations, they frequently suggested papers are not doing enough to advance public understanding of the process. “You get a fantastically different perspective both on how the negotiations are going and the likely results of the negotiations depending on which paper you choose to pick up,” says Moore at King’s College London.

“The frustrating thing is how much of this is a continuation of old battles,” adds Kim Fletcher, editor of the British Journalism Review. “I don’t think we’re learning a huge amount [about what’s happened]. A lot of it is an article of faith at the moment, and the two sides aren’t moving toward each other.”

By doubling down on well-worn opinions, papers can circumnavigate the byzantine technical complexities of the ongoing negotiations—which are difficult even for journalists to master and repackage for readers. “The debate is couched around the idea of a ‘soft Brexit’ or a ‘hard Brexit’ or ‘no deal,’” says Beckett at LSE. “No one really knows what those terms mean. So for journalists, it’s incredibly difficult to get any handle on this.”

That’s not to say the press shouldn’t be sharply critical of the Brexit process when it’s merited—and there’s no question that talks have thus far been beset by a lack of vision, and official intransigence, on both sides. “I did a radio slot on the BBC on Brexit, and at the end of a five-minute interview I realized I hadn’t said a single positive thing, which I felt quite bad about,” says freelance journalist Marie Le Conte. “But I literally could not think of anything positive to say about the way Brexit is going. And so I think it can look from the outside like it’s this onslaught of bad news, and negativity, and pessimism, but also most of Brexit is not really going tremendously at the moment.”

But the British press should help Britain move forward in its policy negotiations, rather than holding the Brexit narrative, and thus the political scene, in a kind of stasis. That doesn’t mean lightening scrutiny, but does mean taking a broader perspective on an inevitably complicated story.

“There are huge realignments taking place in politics, in the media, among ordinary people. One of the problems with the media coverage is they find it almost too fascinating, too difficult, too strange, too peculiar,” says Brendan O’Neill, editor of online magazine Spiked. “They’re constantly trying to force it back into old narratives that don’t quite work.”

ICYMI: Blockbuster White House book claims its first victim

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.