Sign up for the daily CJR newsletter.

On March 15, 2019, a gunman opened fire on worshippers at two mosques in Christchurch, New Zealand, killing 50 and wounding dozens of others. In the wake of the worst terrorist attack in the country’s modern history, Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern declared of the shooter, “He is a terrorist; he is a criminal; he is an extremist. But he will, when I speak, be nameless.” Explaining her decision not to name the shooter, Ardern said, “He sought many things from his act of terror, but one was notoriety. And that is why you will never hear me mention his name.”

Prime Minister Ardern’s position is consistent with the advice of No Notoriety, a media advocacy organization founded by Tom and Caren Teves, whose 24-year-old son, Alex, was killed during a mass shooting in Aurora, Colorado. Their campaign urges the media to report on mass shootings without amplifying the ideology of the attacker. Research on mass violence shows that mass shooters often cite previous gunmen as inspiration for their acts of violence. The New Zealand shooter mentioned mass murderers who killed worshipers in a Charleston, South Carolina church, and a Norwegian murderer who killed 69 political activists and children at a summer camp.

ICYMI: After New Zealand massacre, Islamophobia spreads on Chinese social media

Our team used Media Cloud, an open-source media collection and analysis tool developed at MIT’s Center for Civic Media and Harvard’s Berkman Klein Center, to analyze 6,337 stories in 508 national-level English-language news sources in New Zealand, Australia, Canada, the United Kingdom, and the United States. We found a mix of good and bad news for campaigns such as No Notoriety.

We examined the stories we retrieved for compliance with seven guidelines, compiled from No Notoriety and other campaigns that seek to limit the amplification of terrorist acts through media. While media justice campaigns often seek out journalists as conduits of change, we also expanded our analysis to assess whether internet culture reflects journalistic choices about whether to list the name or ideology of the attacker. We coded for compliance with the following best practices:

- Don’t publish the shooter’s name.

- Don’t link to or publish the name of the forum that the shooter posted on to promote the attacks.

- Don’t link to or publish the name of the shooter’s manifesto.

- Don’t describe or detail the shooter’s ideology.

- Don’t publish or name specific memes linked to the shooter’s ideology.

- Don’t refer to the shooter as a troll or his actions as trolling.

- Follow the AP guidelines for using the term “alt-right” (contain it within quotation marks or modify it with language such as “so-called” or “self-described”).

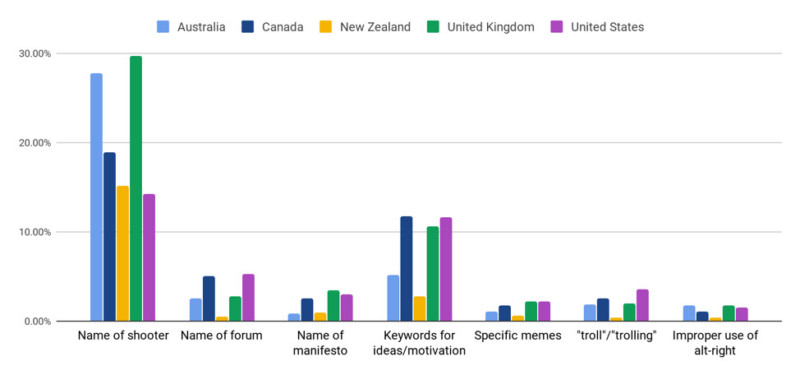

In addition, we coded for stories that focused specifically on the victims or mentioned Islamophobia as a cause in the killings. The graph below shows what guidelines publications in different countries violated.

A week after the attack, none of the sources we analyzed linked directly to the shooter’s white supremacist manifesto or to the online fora where he published his ideas. British paper The Daily Mail had allowed readers to download the manifesto from their site; following criticism, it removed the link.

Prominent US and UK media outlets named the forum the shooter frequented, and many discussed ideas expressed in the manifesto, linking in their explanations to problematic online content. None of the outlets we examined interviewed prominent white supremacists to contextualize the shooter’s ideology. Only 14 percent of US publications reported the shooter’s name, while 30 percent of UK publications ignored this guideline. Despite high compliance with these guidelines, 45 percent of the stories most shared on Facebook included the shooter’s name, and a quarter of the most-shared stories gave information that could leader readers to online discussion of the shooter’s ideology.

The most common violation of these guidelines was mentioning the shooter’s name, followed by mentions of keywords that could lead readers to exploring ideology the shooter had hoped to promote—either through ideas in his manifesto or in phrases written on the firearms he used to commit the murders. Sharing such keywords may be especially dangerous; white supremacists have learned that coining otherwise obscure phrases to promote their ideas gives them high visibility in search engines. These uncommon phrases exploit so-called “data voids”—because there is little content that contains these phrases, extremist content featuring these words will rank highly in search engines.

In other words, searching for phrases that feature in the shooter’s manifesto quickly lead to rabbit holes of extremist content and may serve to recruit readers. By publishing a manifesto and live-streaming his murders, the shooter was clearly aware that he was creating content to recruit future extremists.

Understanding that a mass murderer is consciously seeking to use the media to amplify his extremist views creates a profound challenge for newsrooms. The guidelines suggested to limit the spread of extremist ideologies create apparent conflicts with what most journalists have spent their lives learning to do. Interviewing Tom Teves of No Notoriety, journalism critic Bob Garfield noted, “Our job is pretty much defined by five questions: who, what, when, where, why. And right at the top of the list, is who.” Teves’s explanation that a name has no utility unless there’s an active search for the shooter underway may be satisfying, but the need to withhold details regarding motivation may be more challenging. It feels important to report that the New Zealand shooter was motivated by Islamophobia and by white supremacy rather than mental illness, though the journalistic impetus to show, rather than tell, leads to the trap of amplifying his most viral and sinister ideas.

The Daily Mail, which briefly linked directly to the shooter’s manifesto, violated all seven of the proposed guidelines in their stories. Ninety-eight stories published in the week after the shooting were shared at least 50,000 times each on Facebook and the Mail published 12 of those stories. The Mail also featured the shooter’s name in headlines, published excerpts from the forum post where he announced the shooting, and showed photographs of the weapons he would use, emblazoned with names and phrases designed to promote his cause. The Sun offered similar coverage, including unblurred photos of the gunman and his weapons, and a long article examining the ideas in his manifesto.

UK papers’ willingness to amplify the shooter’s ideas was not limited to tabloids. The Guardian’s US edition also violated all seven guidelines, and five Guardian stories were shared more than 50,000 times each. The BBC violated six of seven guidelines, and their most popular story—which included the shooter’s name and the name of his manifesto—was shared almost 700,000 times on Facebook. The New Zealand Herald, which ran 11 stories shared more than 50,000 times, violated four of the guidelines, more than almost all other New Zealand outlets. Some outlets may look at their social media metrics and conclude that they need to publish sensitive details of the massacre to retain readers. Forty-seven percent of stories shared more than 50,000 times on Facebook included the shooter’s name. (Recall that less than 20 percent of the total stories about the massacre named the shooter.) Stories that were widely shared on Facebook were also more likely to name the shooter’s manifesto (9 percent), the forum he posted on (10 percent), and murderers he cited as an inspiration (9 percent).

While UK media appears especially willing to share the shooter’s name, US and Canadian media were especially likely to discuss the shooter’s ideology and motivations. We found that 106 US stories on the massacre (representing 5.3 percent of the stories we retrieved) mention the forum where the killer shared his ideas, and 231 US stories (11.6 percent) discuss specific ideas and conspiracy theories shared in his manifesto. Five percent of Canadian stories mention the forum, and 11.7 percent mention specific phrases in the manifesto. Several US publications sought to explain references to internet culture in the gunman’s writings. Many of these pieces were insightful—The New York Times’s Kevin Roose, for example, wrote a thoughtful analysis of the ways in which the killings seemed a particularly “online” phenomenon, in a piece that identifies the shooter as well as the forum he posted on, and provides several phrases that lead to conspiracy theories.

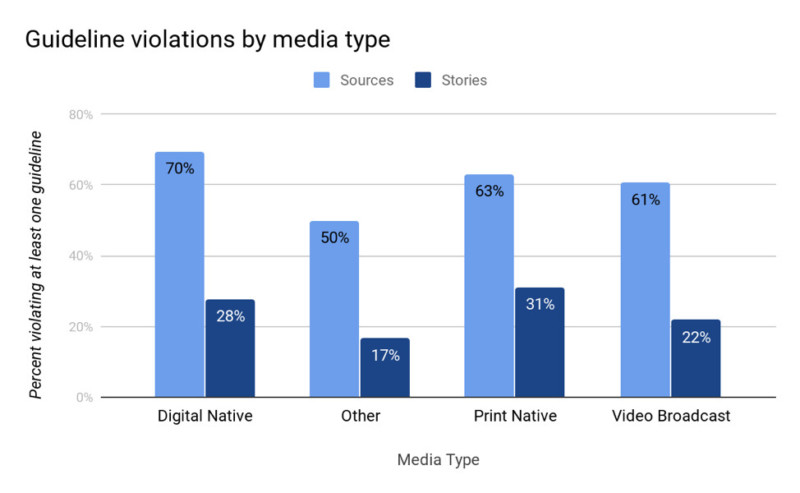

There’s a small difference in adherence to these guidelines between media without a print or broadcast presence, and those that are non-digitally native (see the graph below). However, it’s less significant a difference than the apparent difference in national standards between countries like the US and NZ, which were largely compliant, and those like the UK and Australia, which were less so.

Moreover, giving media attention to the attacker’s ideas displaces other, more pressing public conversations related to Islamophobia internationally. We saw significant differences in use of the term “Islamophobia” across media of different nations.Canadian media included the words “Islamophobia,” “Islamophobic,” or “Islamophobe” in 22 percent of stories, which is twice as high as the usage by media in the next country, the US. New Zealand media only included these terms in 5 percent of stories. On the other hand, New Zealand media published a number of stories that focused on outpourings of support for the country’s Muslim population, from motorcycle gangs serving as mosque defenders to politicians and broadcasters donning hijabs in solidarity with Muslim neighbors. The most popular story of the week following the shooting was a set of biographies of all the victims of the shooting, focusing on their lives and their faith, published by the New Zealand Herald, which was shared almost 1.4 million times on Facebook.

It seems, from our findings, that more journalists are stepping back from the “who, what, where, how, and why” to questions of how to prevent tragedy. With platforms as a distribution system, this problem is much more complicated. Digitization has made local news globally accessible, and it’s a very short distance from “It can’t happen here” to “It’s happening everywhere.”

ICYMI: New Zealand massacre: Journalists divided on how to cover hate

Correction: A previous version misspelled Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern’s name.

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.