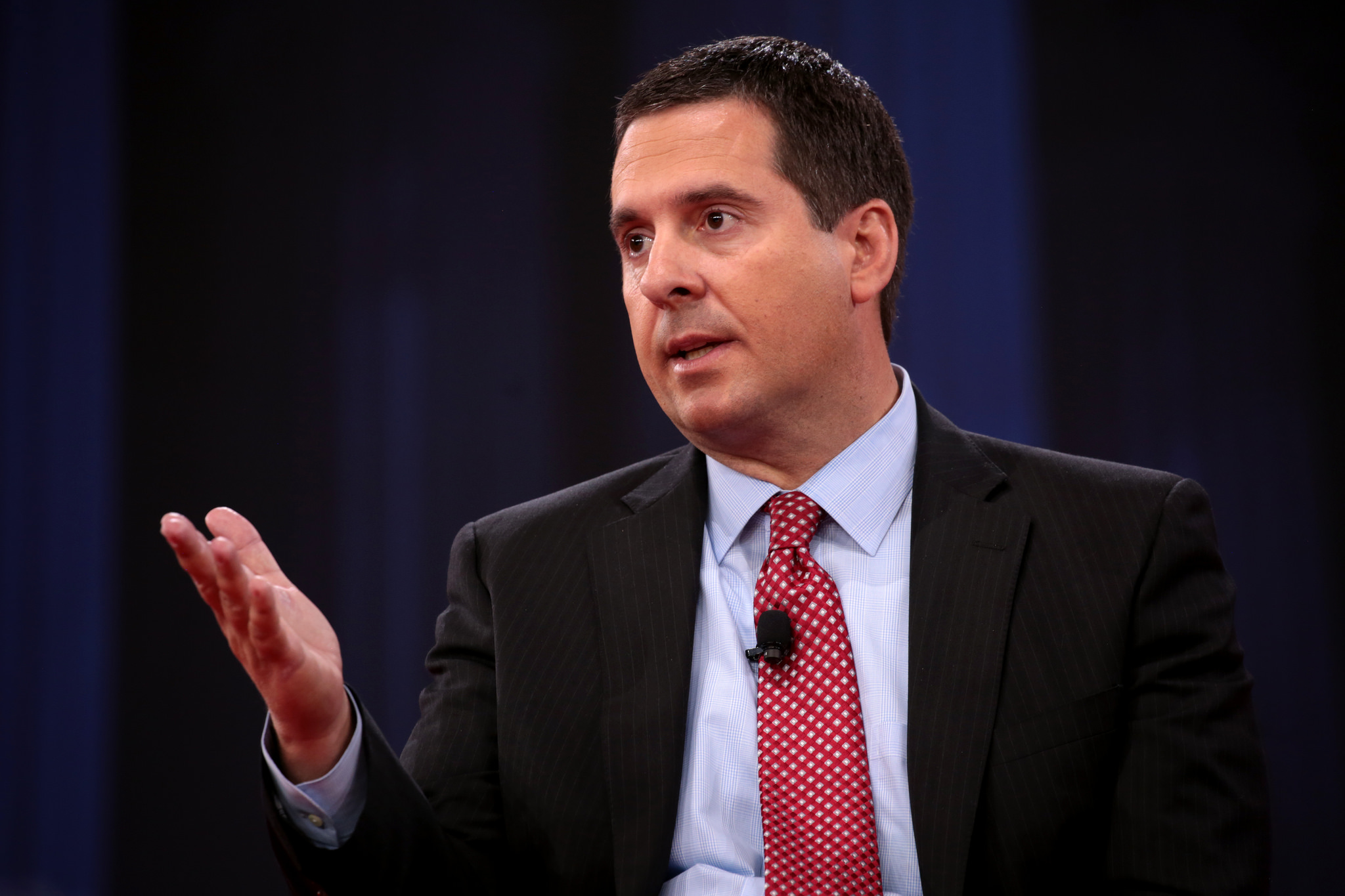

The defamation suit Congressman Devin Nunes filed Tuesday against Twitter has less of chance of succeeding than my NCAA Tournament bracket.

The California Republican’s lawsuit, which contends three Twitter users defamed him and the social media platform is liable because it allowed the comments to be published, might have one important shred of value. It highlights the untenable level of double protection from liability that social media platforms have come to receive.

Let me explain. If Nunes sued a newspaper for defamation, he would face the exceedingly difficult task of proving that the publication had published the information with “actual malice,” that is, with knowledge that the information was false or with a disregard for whether it was true or not. This was the standard that was established in New York Times v. Sullivan in 1964, and has become a part of the bedrock of the free press.

ICYMI: WSJ reporter explains why he was fired

Nunes’s case won’t even get that far. All Twitter’s lawyers have to do is invoke Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act and his case should, by all accounts, be dismissed. While the lawsuits against individual users can proceed based on their merits, CDA 230, which was passed in 1996 during the infancy of the Internet, stipulates that “No provider or user of an interactive computer service shall be treated as the publisher or speaker of any information provided by another information content provider.”

Over time, social media companies have come to be categorized as “interactive computer services,” meaning they are essentially immune from liability for how people use them. This categorization has persisted even as these corporations have delved, more and more, into deciding what information users encounter and what they do not and as they have started to monitor posts and remove content based on certain community standards.

While such a protection has been crucial to the formation of the internet as we know it, it has, as tech giants such as Facebook and Google have grown into leading media companies, created an environment where these companies have significantly more rights than citizens and news organizations – essentially a double shielding from liability.

In the Nunes case, this means he must defeat CDA 230 and the Sullivan actual malice standard to win, essentially the equivalent of scaling two Mount Everests. If he sued the Washington Post he would face only one of these formidable mountains.

This should not be. The Supreme Court has long declined to extend additional rights to one group over and above those held by others. Famously, in Branzburg v. Hays in 1972, the Court declined to extend journalists rights that go beyond those available to others.

But acknowledging these unintended consequences of CDA 230 does not mean the law should be deleted. It should instead be revised. In particular, its definitions of “publisher” and “forum provider,” must be clearly outlined with the emerging, twenty-first century Internet in mind.

The definition of a publisher should more closely mirror the expectations that journalists face in their work each day. Organizations that outline expectations and ethics for what is published and edit or delete certain accounts and posts, should be considered publishers. In other words, social media outlets should be expected to take some responsibility for what they publish – just as news organizations are.

It could be argued these changes might incentivize the companies to stop any kind of moderation, and allow anything at all to propagate, but history has shown that the marketplace generally does not support “cyber cesspools.” Sites like JuicyCampus and Yik Yak, which were criticized for enabling the worst online behavior, were short-lived. As legal scholar Eric Goldman emphasized, “cyber cesspools develop terrible reputations and become poor business investments.”

Jacinda Ardern, the Prime Minister of New Zealand, communicated similar concerns Tuesday as her nation mourned a terror attack, overtly inspired by online hatred, and seeking to inspire it in others, that killed fifty people last week.

“We cannot simply sit back and accept that these platforms just exist and that what is said on them is not the responsibility of the place where they are published,” she told her nation’s parliament. “They are the publisher. Not just the postman. There cannot be a case of all profit and no responsibility.”

ICYMI: For the record: 18 journalists on how—or whether—they use tape recorders

Similar delineations regarding publishers and platforms have roots in the origins of CDA 230. A year before the law was passed, in Stratton Oakmont v. Prodigy, a New York state court found an internet service provider was liable for defamatory information that was posted on message boards it hosted. The judge determined the ISP had transitioned from a forum-provider to a publisher by moderating the content on the forums.

But in our zeal to protect online expression, we can forget that all of the communication that occurs in online spaces is protected by the First Amendment and that the Supreme Court has made it clear corporations receive citizen-like free expression protections as well.

So revisions to CDA 230’s definitions would not suddenly halt expression on the Internet (Even leaving aside the fact that these companies are unlikely to walk away from billions of dollars in advertising and personal data collection and resale that their platforms yield for them each year.)

Take Nunes’s defamation case, for example. Absent CDA 230 protection, would Nunes’s defamation suit against Twitter succeed? It’s unlikely. Nunes would have to prove that Twitter published the users’ content with malicious intent and that the information was something more than opinion, satire, or parody, all of which are legal defenses against defamation.

In short, existing defamation precedent is a relatively robust shield against frivolous defamation claims. The concern, however, is that the constant threat of lawsuits would chill companies from providing such online forums.

One solution would be to fight for stronger anti-SLAPP laws, which allow those who are attacked by frivolous defamation lawsuits to have the cases quickly dismissed with their legal fees, at times, paid by the person who brought the frivolous suit.

A federal anti-SLAPP law, created at the same time as revisions to CDA 230, would also help counter the types of abuses forum providers might face. Such a solution would create more consistency in the law, rather than allowing some publishers to receive First Amendment-plus protections, granting them the First Amendment protections of publishers and CDA 230 safeguards as forum providers.

CDA 230 has acted as a vigilant defender of online forums since the Internet’s infancy. As the Internet evolves, maybe it’s time CDA 230 does as well.

Jared Schroeder is an assistant professor of journalism at Southern Methodist University, where he specializes in First Amendment law. He is the author of The Press Clause and Digital Technology’s Fourth Wave.